Shutterstock.com

Although not an inevitable consequence of ageing, frailty — now recognised as a long-term condition in its own right — will become increasingly prevalent as people continue to live longer. However, there are concerns that patients with frailty are not getting the basic care they need to prevent adverse drug reactions and unplanned hospital admissions.

Frail patients are often more susceptible to side effects of medicines and may experience falls, incontinence, delirium and immobility. They tend not to recover as well from events such as infections or starting a new medicine and are frequent users of the healthcare system[1]

.

Medicines reviews are a crucial part of managing frail patients as the effects of reduced renal function, lost body mass, cognitive decline, postural hypotension and increasing susceptibility to side effects can all combine to put the patient at risk from medicines that were once prescribed to help.

For the first time we said, officially, that frail people need different care

Under NHS guidance introduced in October 2017, GPs in England should be routinely identifying frail older people, and those with ‘severe frailty’ should be given an annual medicines review – a move described as “an absolute sea change” for frailty care by Andrew Green, a GP in East Yorkshire and former clinical lead for the British Medical Association’s (BMA’s) GP committee.

“For the first time we said, officially, that frail people need different care,” he explains.

However, NHS Digital data analysed by The Pharmaceutical Journal suggest that medicines reviews are still not happening for tens of thousands of frail patients[2]

.

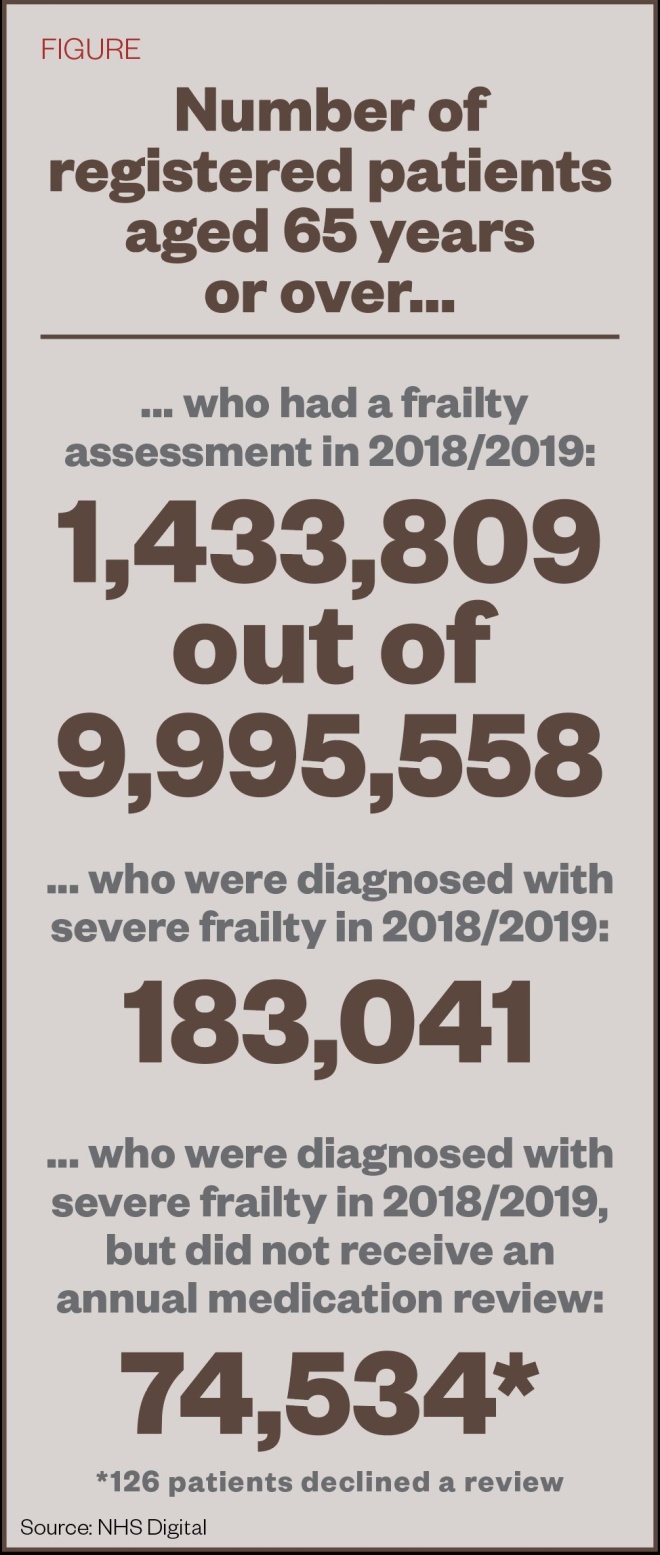

According to the data, in 2018/2019, medicines reviews were conducted for only 59% (108,507) of older people assessed as being ‘severely frail’, leaving four in ten (74,534) vulnerable patients without a review (see Figure).

Source: NHS Digital

Figure: Thousands of frail older patients are missing out on medicines reviews

The lack of reviews in some patients is a vital missed step. “This seems like a very low number [receiving medicines reviews],” says Henry Woodford, chair of the British Geriatric Society’s Medicine Optimisation Special Interest Group and a hospital-based geriatrician.

“Many of these patients will be in the last year of their life and it would seem entirely appropriate to do a medication review,” he adds. “Studies suggest that, in frail older people, at least 10% of admissions are directly related to medicines, and that they play a smaller contributing part in many other admissions.”

David Reeves, senior researcher at the Centre for Primary Care, Institute for Population Health at the University of Manchester, says some GPs may not be fulfilling the frailty initiative because of a lack of resources.

The NHS Digital data show that only 14% of registered patients aged 65 years and over received a frailty assessment in 2018/2019, with 26% receiving an assessment in 2017/2018.

Almost 350 GP practices did not assess a single patient in 2018/2019.

One of the biggest barriers to screening for frailty is the gap between patient need and service provision, explains Reeves, whose team has conducted qualitative interviews with GP practices.

Some GPs may only be paying lip service to the frailty initiative because of a lack of resources

“GPs are concerned about identifying large amounts of need that they are unable to meet because of a lack of available local resources,” says Reeves.

“This has resulted in quite a lot of practices paying only lip service to the frailty initiative, which is one reason why the medication review rate is low.”

Another reason is that GPs are already over-stretched regarding workload, he adds, and “the government has provided no additional resources to support the initiative”.

However, Richard Vautrey, GP committee chair at the BMA, cautions that the figures may say more about coding and recording. “A clinician will review the medication … when they see patients or a prescription is done, but [they] may not necessarily code this,” he suggests.

The importance of medication reviews will be reinforced through the forthcoming PCN service specification on structured medication review

Whether or not this is the case, NHS England is determined to ensure reviews happen. Its draft primary care network (PCN) service specification, published in December 2019, recommends that from 2020; PCNs should use clinical pharmacists, GPs and advanced nurse practitioners to carry out structured medication reviews for frail older people[3]

.

“The importance of medication reviews will be reinforced through the forthcoming PCN service specification on structured medication review, which … will start in 2020,” says a spokesperson for NHS England and NHS Improvement.

“This enhanced requirement is being supported through the deployment of thousands of clinical pharmacists into PCNs as part of our wider proposals for PCNs to recruit over 20,000 additional staff,” they add.

However, pharmacists have raised concerns that the sheer number of people needing structured medication reviews, which also target seven other patient groups, could result in reviews that prioritise efficiency over thoroughness.

Defining frailty

There are plenty of tools designed to measure frailty, yet currently there is no gold standard and it is not something that can be accurately quantified. In addition, there are overlaps with multimorbidity, which can further confuse the picture when medical conditions have been treated separately to each other.

GPs use the electronic frailty index (eFI) to flag patients at risk of frailty — a system that takes information from the electronic primary healthcare record. The eFI estimates that 3% of the population aged 65 years and over in England live with ‘severe frailty’, 12% live with ‘moderate frailty’ and 35% with ‘mild frailty’[4]

. Once patients are identified as being at risk of frailty, clinical judgement must be used to make a diagnosis.

Ali Hasan is a specialist frailty pharmacist with the Proactive Ageing Well Service in Islington, North London. He takes patients who have been identified by the eFI to look in more detail at the ‘moderates’ and ‘don’t knows’.

By phone, Hasan uses the PRISMA 7 questionnaire (see Box 1) to identify who may need help out of those who score three or more, before asking in more detail about falls, continence issues, memory, mood, and what help the patient receives.

Box 1: PRISMA 7 questions

- Are you over the age of 85 years?

- Are you male?

- In general, do you have any health problems that require you to limit your activities?

- Do you need someone to help you on a regular basis?

- In general, do you have any health problems that require you to stay at home?

- In case of need, can you count on someone close to you?

- Do you regularly use a stick, walker or wheelchair to get about?

Source: BCGuidelines.ca

After visiting the service, run by a multidisciplinary team, in August 2019, NHS England found it to be the type of programme it would like to see rolled out nationwide, according to Hasan. Since the start of 2018, the service has saved £33,000 in cuts to polypharmacy, around £275,000 in hospital avoidance and reduced falls by 50%. It has seen 852 patients to date, each of whom sees the team an average of 2.5 times.

“There are lots of problems you find with medicines. One of the common ones is inhaler technique: no one takes them properly and if they’re not using it properly, they’re not getting much benefit. [They] may as well stop it,” says Hasan.

Medicines mismanagement, such as taking too many painkillers, is another problem the team deals with regularly, he says.

“compliance is also an issue and, in that case, we would work to rationalise medicines to what’s important to the patient,” he explains.

All patients have a postural blood pressure check and are often taken off of antihypertensives to prevent falls, which is a common step during a review of patients’ medicines, he adds. Indeed, the NHS Digital data show that 12% of patients diagnosed with ’moderate’ or ‘severe’ frailty had a fall within the past 12 months[2]

.

Generally speaking, the frail patients Hasan sees do not want to take a lot of tablets, especially those that give them side effects.

“[These patients’] priorities have changed and they can’t see the benefit [of multiple tablets]. You come across side effects a lot, particularly [with] tramadol and anticholinergic drugs like amitriptyline. What you find is that a lot of patients titrate themselves [by reducing the dose].”

Pharmacists’ role

With pharmacists poised to take on a greater role in the care of frail patients, Green is among those who believe that the wider primary care team is going to have to adapt.

“It was only when I saw the medicines reviews done by my practice pharmacist [that] I realised how sketchy my own medicines reviews had been,” he says.

It was only when I saw the medicines reviews done by my practice pharmacist [that] I realised how sketchy my own medicines reviews had been

Woodford points out that it will be important to define what a medication review involves. “I suspect that sometimes it works really well to the GP, pharmacist and patient’s satisfaction, and sometimes it becomes a tick-box exercise.”

In most cases, a successful medicines review will involve deprescribing.

“Many of the [healthiest] frail patients are on next to no medication,” says Green. “Yet a patient who is independent and is being threatened by a painful knee might need an increase in medication to keep that independence. Those difficult decisions are where the GP can play a particular role.”

Hasan’s team is currently trying to build relationships with practice pharmacists and, in his view, as long as they have received the necessary training, they are in a great position to carry out medicines reviews for frail older people.

“We see a lot of patients on a lot of medicines who haven’t been reviewed for many years, but this cohort of patients is complicated and there are cognitive issues as well,” he explains. “If pharmacists can have 20–30 minutes, they can look at a patient’s medicines in much more detail, and they will probably be more aggressive with deprescribing as well,” he says.

If pharmacists can have 20–30 minutes, they can look at a patient’s medicines in much more detail, and they will probably be more aggressive with deprescribing as well

David Wright, professor of pharmacy practice at University of East Anglia, suggests that putting standards in place for managing these complicated patients would provide reassurance for GPs that these patients — the most frail and complex on their list — will be safe.

“These are not single diseases and it is not a matter of simple guidelines. You have patients who have a range of different conditions and it’s not black and white,” he says.

Wright, who set up CHIPPS (Care Homes Independent Pharmacist Prescribing Study) to assess pharmacists taking responsibility for medicines management in care home patients, explains that in response to GPs’ concerns, his team put in place a specially designed training and competency framework for pharmacists. Findings from CHIPPS are expected to be reported in 2020.

As practice and primary care network pharmacist roles grow, it will be worth them bearing in mind that home visits can be important, says Ana Armstrong, lead pharmacist in the community medical team at NHS Surrey Downs Clinical Commissioning Group.

You are so much more effective when you visit frail patients at home

“You are so much more effective when you visit frail patients at home,” she says. “You can tell so much more about how they are coping. And you need time,” she adds. “If you have a really complex patient, it can take a while to get to the bottom of why they are on a certain medication. It may be the evidence has changed or gradually other medicines have dropped off and they are left on a random combination” (see Box 2).

It is this check on how frail patients are managing their medicines that is often missing, according to Jennifer Stevenson, clinical academic pharmacist at King’s College London, who specialises in the optimisation of medicines in older adults. Doctors generally know that, because of the ageing process and physiological changes, drug doses need to be modified or certain drug classes should be avoided. However, they often do not look at how patients manage their medicines, she explains.

“You need a multidimensional approach, it needs to be structured and part of a bigger package of interventions, and you need someone coordinating that approach,” she argues.

“There is a huge amount more we can do and using the pharmacy skillset appropriately does seem to be a good starting point.”

Box 2: Case studies

Ana Armstrong, frailty pharmacist, Surrey Downs Clinical Commissioning Group:

“We had a patient who was approaching the end of her life. She was taking lots of cardiac and Parkinson’s disease medicines. Her blood pressure was low and she was really unsteady on her feet — mostly bed bound. Her son was responsible for her tablets, which she kept in a dosette box, and she was taking 30 different tablets a day.

Her son was aware that she only had a short time left. We cut out her alendronate, a bisphosphonate medicine used to treat osteoporosis and Paget’s disease of bone, and her statins. We also reduced her antihypertensives and optimised some of her Parkinson’s disease medicines because she was on a strange combination owing to medicine supply problems. When we had completed the review, we had cut out 14 doses without removing many medicines; optimising them instead. It was really satisfying as it made such a big difference to them both and is was something no one else had picked up on.”

Lelly Oboh, consultant pharmacist, Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Trust:

“A female patient aged 73 years was referred to our team because of concerns over her medicines. She was taking 15 medicines in 19 daily doses, but she wasn’t taking all of them despite education and the introduction of a blister pack by another pharmacist. Her diabetes was not well controlled, and she had fallen a few times recently. We did medicines reconciliation, ordered some tests — including for postural hypotension — and looked at her unmet needs. We changed her medicines ordering and delivery systems to solve problems she had been having with supply. We also involved the community pharmacist for a couple of weeks to help her with a new insulin device she had been struggling with. Her metformin was switched to a modified-release formulation, she was taken off oxybutynin and quinine and her statin dose was lowered; all to help reduce the side effects that she was experiencing. For her neuropathic leg pain, her gabapentin dose was optimised and she was taken off of paracetamol and Movelat Gel (salycylic acid; Genus) which she didn’t think were helping. To address the problem of falls, her doses of ramipril and amlodipine were reduced, with no problematic knock on effect to her blood pressure. Overall she was moved to ten medicines in seven daily doses, ending up much more in control of her insulin without compromising her independence. Her pain control and gastrointestinal symptoms also improved.”

References

[1] British Geriatrics Society. 2014. Available at: https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018-05-23/fff_full.pdf (accessed January 2020)

[2] NHS Digital. 2019. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/gp-contract-services/2018-19/gpprac1819 (accessed January 2020)

[3] NHS England. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/network-contract-directed-enhanced-service-des-specification-2019-20/ (accessed January 2020)

[4] Clegg A, Bates C, Young J et al. Age and Ageing 2016;45(3): 353–360. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw039