McLean

Anticoagulation required a substantial rethink early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

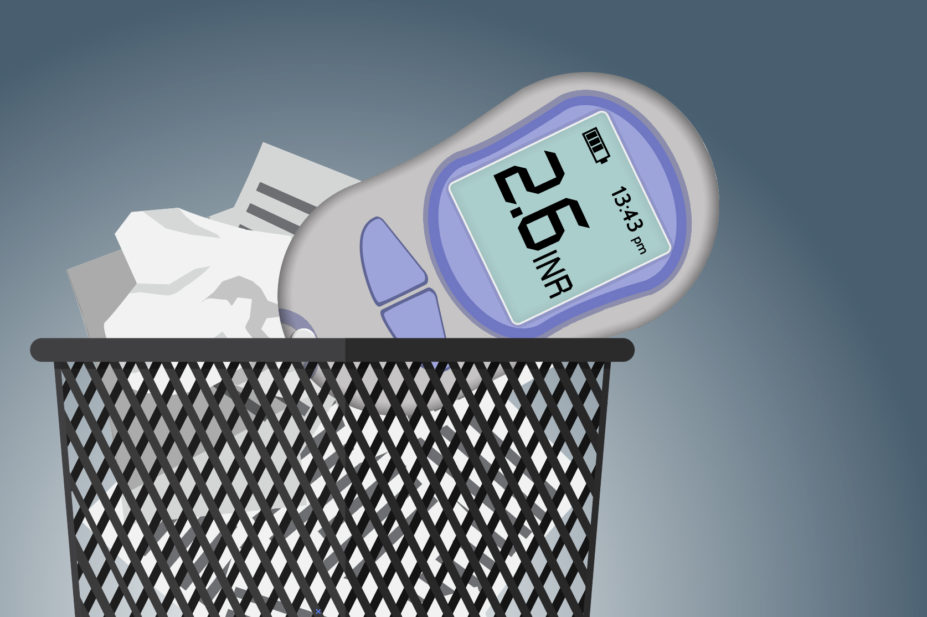

When the UK government announced a national lockdown on 20 March 2020, several factors came together to make monitoring patients treated with the anticoagulant warfarin more difficult, including patients becoming unwell or being reluctant to leave their homes, as well as a rise in demand for district nursing services, leading to delays in international normalised ratio (INR) testing[1].

In response, NHS England published guidance to aid a pragmatic approach to switching patients from warfarin to a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) to avoid the need for regular monitoring (see Box)[2].

“NHS England was very quick off the mark with the guidance it issued in March [2020], which was helpful,” says Lynne Garforth, an advanced practice pharmacist, who runs an anticoagulation clinic within a GP surgery.

“On paper, it was quite a practical approach to the scenario.”

However, what appeared straightforward on paper was a different matter in practice.

Stumbling blocks

Results from a population cohort-based study — carried out on behalf of NHS England, using routine clinical data from more than 17 million adults in England — found that between March 2020 and May 2020, 20,000 out of 164,000 patients originally on warfarin were switched to a DOAC[3]. But there was a sharp rise in potentially unsafe co-prescribing of warfarin and a DOAC, from 50–100 patients per month before the pandemic to 246 in April 2020 — described as a small but substantial number.

In October 2020, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) warned that it was aware warfarin treatment had been continued in a small number of patients after starting treatment with DOACs[4].

To address this co-prescribing, the MHRA reminded healthcare professionals to ensure that warfarin treatment was stopped before DOACs were started.

And, in July 2021, a “safety critical” National Patient Safety Alert from NHS England ordered that more than 700 patients with a mechanical heart valve who had been switched to a DOAC during the pandemic should be reviewed urgently[5].

According to the alert, 14 incidents had been reported since 1 March 2020, in which patients with a mechanical heart valve had been switched from warfarin to a low molecular weight heparin or a DOAC. In two of the incidents, the patients were hospitalised owing to valve thrombosis and/or required emergency surgery, and one was admitted with severe anaemia.

The practicalities of applying quite a logical guidance … quickly became a little bit unworkable

Lynne Garforth, advanced practice pharmacist

While these serious incidents were relatively rare, considering the number of patients eligible for switching across the country, it illustrates just how challenging it can be to make widespread switches at this scale.

“What quite quickly manifested itself was that, in order to [switch patients], one of the first things we’ve got to look at is: have we got baseline bloods for kidney function, liver function and the blood count?” recalls Garforth.

“If [the blood tests] were longer than three months ago, that was really classified as being too old.

“And that was a massive issue really early on; the phlebotomy services went to a very limited capacity — we could only refer for urgent bloods and there were very few appointments.”

Garforth works in Lancashire and Liverpool and says that the walk-in phlebotomy services in both regions simply “ground to a halt” and, without access to up-to-date blood results, switching became a “no go” for a lot of patients.

“We were kind of stuck right at the first hurdle,” Garforth adds. “The practicalities of applying quite a logical guidance … quickly became a little bit unworkable.”

For those patients who were able to switch, it was difficult to try to find the time for those crucial conversations to allow patients to process the information being conveyed.

“You’d think it would be quite an easy sell to people, you know, we’ll swap you on to something that doesn’t need monitoring. But it’s not that easy; patients have lots of questions, you’ve got to do lots of counselling around this,” explains Garforth.

“I have ten minutes but even that isn’t sufficient for a full-blown conversation about swapping somebody from warfarin to a DOAC.”

For some patients, the regular contact required with INR monitoring was something they were not willing to give up.

“For some of these people, coming in for their warfarin appointment was about the only thing they could do,” says Katherine Stirling, a consultant pharmacist specialising in anticoagulation and thrombosis at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

“That contact ended up being really important — we had to convince a 99-year-old not to get the bus to the warfarin clinic.”

Stirling, whose team runs clinics across Leeds, had around 6,500 patients still on warfarin at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and has now successfully switched over 2,000 of them — half in the first nine months of the pandemic.

I think some of them felt forced to switch because of the pandemic

Katherine Stirling, consultant pharmacist specialising in anticoagulation and thrombosis at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

For the patients who were deemed suitable for DOACs, it was ‘all hands on deck’ to get them switched as quickly and efficiently as possible; Stirling’s team were joined by two consultant haematologists, the clinical commissioning group GP confederation pharmacy team in primary care and, when they were able to, other pharmacists in the trust.

Stirling explains that they tried to phone each person first but, because of the number of patients, some had to be picked up when they came into the clinic. Some patients were “desperate” to switch, she recalls, while for others she had to phone them “four or five times” to talk about the switch.

“I think some of them felt forced to do it because of the pandemic … how we prepared patients made a difference to those discussions.

“You have to be listening very hard [over the phone] to pick up on the nuances or if somebody is not understanding — it’s a different skill than it is if you’re seeing someone face to face,” she adds.

“Rushing affects the quality of the conversation and can cause some errors.”

Box: The switching guidance

Switching appropriate patients from warfarin to a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) may be considered to avoid regular blood tests for international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring. Anticoagulation service provision should consider the following:

- Is warfarin still required?

- This is an opportunity to review if long-term warfarin therapy is still indicated — for example, in patients with prior deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, for whom the risk of recurrence is now considered low

- Can patients on warfarin be switched to an alternative oral anticoagulant, such as a DOAC?

- While DOACs do require blood tests to assess renal function throughout treatment, the monitoring is predictable, less rigorous than INR testing with warfarin and routinely carried out in primary care.

Patients should only be switched from warfarin to a DOAC by clinicians in primary or secondary care with experience in managing anticoagulation.

The most appropriate DOAC should be chosen according to:

- therapeutic indication;

- patient age;

- actual bodyweight;

- renal function — calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl);

- drug interactions;

- patient preference/lifestyle.

In line with guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, where more than one product is available for the indication, the product with the lowest acquisition cost should be used.

A switch from warfarin to a DOAC should not be considered for patients:

- with a prosthetic mechanical heart valve;

- with moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis;

- with antiphospholipid antibodies;

- who are pregnant, breastfeeding or planning a pregnancy;

- requiring a higher than standard INR range of 2.0–3.0;

- with severe renal impairment (CrCl less than 15mL/min);

- with active malignancy/chemotherapy (unless advised by a specialist);

- prescribed some HIV antiretrovirals and hepatitis antivirals — check the HIV drug interactions website

- on phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbitone or rifampicin — these patients are likely to have low DOAC levels so should be discussed with an anticoagulation specialist;

- with venous thrombosis at unusual sites because there is little data on DOACs for this patient group — these patients should be discussed with an anticoagulation specialist;

- on triple therapy (dual antiplatelet plus warfarin) — switching these patients should be discussed with an anticoagulation specialist or cardiologist[2].

Adherence issues

With significantly fewer patients requiring INR monitoring after being switched, it has inevitably led to concerns among those working in anticoagulation services that their roles may become redundant.

“I think, particularly the biggest services, do become worried about their jobs if we’re swapping all these patients from warfarin to DOACs,” says Garforth.

“But it is very much about the leaders within that team thinking outside the box; this can look like a different service — there’s still an awful lot to do around getting people diagnosed … and around keeping the ongoing prescribing of DOACs safe.”

Garforth explains that ongoing care with DOACs is not currently done “very well”; in some cases, patients stop taking them and it is not picked up for weeks.

If you look at the literature, levels of non-adherence to DOACs are significant

Rani Khatib, consultant pharmacist in cardiology and cardiovascular reserach at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Rani Khatib, a consultant pharmacist in cardiology and cardiovascular research at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, agrees that adherence to DOACs is “an area of concern”.

“If you look at the literature, levels of non-adherence to DOACs are significant,” Khatib explains.

“When you are on long-term medicines, your adherence drops — something in the region of 30–50% non-adherence.”

According to a UK population-based study published in 2019, DOACs have a reported 65.9% adherence rate at one year[6]. And patient adherence can be affected by numerous factors, some of which may be influenced by the quantity or quality of the interaction between clinician and patient — for example, if consultations are less frequent or whether they are remote or face to face[1].

To explore this further, Khatib is currently running a research project to determine levels of non-adherence to DOACs across Leeds, with the aim of developing an intervention to improve adherence that can be deployed across GP surgeries and pharmacies.

“Sometimes, a simple phone call to the patient can actually make them share with you their medicines-taking experience and you might identify issues and areas that need exploring,” he says.

As well as adherence, Khatib explains that underdosing is an issue with DOACs.

“Clinicians tend to be worried about the risk of bleeding. For example, if you take a frail patient, [the clinician] will probably opt for a lower dose of a DOAC, despite the fact the evidence says, in that patient population, giving a full-dose DOAC is safe and nothing to worry about.”

A positive change

From Stirling’s perspective, the switching process has transferred a lot of work to primary care and provided the opportunity for learning. She has been working closely with her colleagues in primary care to ensure they are upskilled to be able to carry out follow-ups with patients and feel confident enough around anticoagulants to be able to switch and initiate them.

Nationally, it’s given people a push to consider swapping people from warfarin to DOACs

Lynne Garforth, advanced practice pharmacist

Garforth observes that, although the process has come with its challenges, it also provided the motivation required to switch patients who were eligible according to the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on management of atrial fibrillation, and who would potentially fare better on DOACs.

“Nationally, it’s given people a push to consider swapping people from warfarin to DOACs,” she says.

“Some clinicians may have been a bit complacent about that in the past and patients might have been plodding along on quite poorly controlled warfarin, despite the NICE guidance.”

And the drive to scale up the use of DOACs continues. In November 2021, NHS England announced that it had struck a deal with three manufacturers — Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer and Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), on behalf of the BMS/Pfizer alliance — to make DOACs more affordable, allowing local NHS systems to provide them to 610,000 additional patients with atrial fibrillation in England. In a statement on 16 November 2021, NHS England said that expanding the use of DOACs would “help prevent an estimated 21,700 strokes and save the lives of 5,400 patients with a fatal outcome over the next three years”.

Carrying out switches remotely has also shown how online and phone consultations can have a role in anticoagulation clinics and wider healthcare, alongside face-to-face consultations.

The success of remote switching was highlighted in a report submitted to Thrombosis Research in January 2021 by staff at King’s College Hospital Foundation NHS Trust, who carried out a survey of 186 patients switched from warfarin to a DOAC over an eight-week period[1].

The survey results showed that 80% of patients rated the quality of their virtual consultation as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’, and more than half expressed a preference for virtual consultations compared with face to face because of the convenience.

In Leeds, a survey carried out by Stirling’s colleagues revealed that some staff thought it was difficult to fully assess certain patients without physically seeing them, and sometimes found it difficult to gauge patient understanding over the phone. Despite this, most clinicians thought that telephone appointments were as suitable as face-to-face appointments in around 50–70% of cases.

Anticoagulation services need to be a bit more innovative

Rani Khatib, consultant pharmacist in cardiology and cardiovascular reserach at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Ramping up the DOAC switching programme during the COVID-19 pandemic has clearly presented significant challenges for anticoagulation teams, some of which are still being worked through. However, it has also highlighted opportunities for new, and potentially improved, ways of managing patients on anticoagulants.

“Anticoagulation services need to be a bit more innovative and think about how to use all these people who are very skilled in what they do to address the wider issue of thrombosis and anticoagulation,” says Khatib. “I can see that they will evolve to provide something else.”

Garforth agrees that the process has provided the opportunity for new thinking around anticoagulation.

“The reality is, there’s going to be less and less patients needing dosing on warfarin and that will concern people,” says Garforth, “but there’s plenty of other things that can be done with patients and keeping them safe on DOACs.

“It’s just being a bit creative about what you do with your time and focusing your efforts on where that need has moved to now.”

- 1Patel R, Czuprynska J, Roberts LN, et al. Switching warfarin patients to a direct oral anticoagulant during the Coronavirus Disease-19 pandemic. Thrombosis Research. 2021;197:192–4. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.004

- 2Clinical guide for the management of anticoagulant services during the coronavirus pandemic. NICE. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/about/covid-19/specialty-guides/specialty-guide-anticoagulant-services-and-coronavirus.pdf (accessed 30 Nov 2021).

- 3Curtis HJ, MacKenna B, et al. OpenSAFELY: impact of national guidance on switching from warfarin to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in early phase of COVID-19 pandemic in England. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.12.03.20243535

- 4Warfarin and other anticoagulants – monitoring of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2020.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/warfarin-and-other-anticoagulants-monitoring-of-patients-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/warfarin-and-other-anticoagulants-monitoring-of-patients-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed 30 Nov 2021).

- 5Inappropriate anticoagulation of patients with a mechanical heart valve. National Patient Safety Alert – NHS England & NHS Improvement. 2021.https://www.cas.mhra.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAlert.aspx?AlertID=103164 (accessed 30 Nov 2021).

- 6Banerjee A, Benedetto V, Gichuru P, et al. Adherence and persistence to direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a population-based study. Heart. 2019;106:119–26. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315307