Charlie Milligan

“I’m in the office today,” says Nigel Clarke, outgoing chair of the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC), as he makes a gesture that takes in the crisp white walls, neatly-filled bookshelves and the distinctive delftware pharmacy jars of the pharmacy regulator’s London headquarters.

It is a small but poignant illustration of just how much the COVID-19 pandemic changed our way of life — for many of us, being physically present in the office is still something of an occasion.

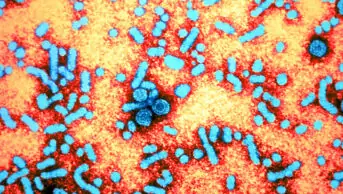

When the virus reached UK shores in early 2020, the GPhC had to react quickly. As Clarke says: “It was clearly a serious health issue, but it was also very clear that, in the beginning, none of us really knew anything about it. We didn’t know how serious it actually was. Nor did we know how contagious it was. You had to assume the worst in relation to all of these things.”

The creation of the provisional and temporary pharmacy registers, as well as the shift to online registration assessments, were just some of the things the GPhC oversaw as part of its COVID-19 response.

These pandemic responses are just one small part of how dramatically the pharmacy landscape has shifted in the eight years since Clarke first entered those offices.

His tenure has overseen big changes to the education and training of early career pharmacists, as well as the introduction of revalidation, the growth of independent prescribing and the explosion in online pharmacy.

Before he handed the baton to Gisela Abbam on the 14 March 2022, The Pharmaceutical Journal asked Clarke for his reflections on eight years of change.

You were chair of the General Pharmaceutical Council during a global pandemic. What were your experiences for that time?

It became very clear to Duncan [Rudkin, chief executive of the GPhC], the team and I right at the beginning [of the COVID-19 pandemic] that the single most important thing to protect the public was to make sure that pharmacy continued to deliver services.

We were asked by the NHS to see whether we could try to make sure that any retired pharmacists or pharmacy technicians could rejoin the register as soon as possible. As a result, around 6,000 pharmacy professionals were given temporary registration.

We also created the provisional register, so that those who were in preregistration training could also join the register provisionally to allow them to continue to practice.

We then set up the new registration assessment regime, which had a few teething problems. There were things that, with hindsight, we should probably have double checked: some people had difficulties in finding a venue to book into first time around; there was a problem with overseas students.

In the end, by the time we’d run the third set of examinations on this basis we were in a position to close the provisional register and to say that in the immediate future, the registration assessment will be done in the new format.

There is now a question for my successor and council going forwards as to whether the registration assessment is the best way of determining whether people meet the standards to be able to register — and I think that needs to be revisited.

The updates to pharmacist initial education and training were another huge development from your time in office. What are your hopes for this in the future?

This one really is essential for the future. The principal things here were for there to be greater training alongside other healthcare professionals and to make sure that there was more patient-centred content in the education that was taking place, so there is a stronger clinical feel to it. Integrating the fifth year — the preregistration year, previously — into the formal sets of desired outcomes was also absolutely essential.

A lot of the focus has been on independent prescribing as part of initial training, but we need to be thinking carefully about what the impact of that will be. Under what circumstances will pharmacists be prescribing? If someone’s medicines regime has changed, can we be certain that the next healthcare professional they consult will be able to see not only that the change has been made, but why it has?

There are some quite big questions that are outstanding; important questions about making sure that risk is removed from the way patient care is managed.

Revalidation was another big development during your time as chair — is there any evidence that it is improving patient care?

It’s extremely difficult to tell and the COVID-19 pandemic got in the way, if I’m honest.

I think that revalidation is an area that we need to be refocusing on. Broadly speaking, the new structure of revalidation was popular with pharmacists who felt it was less of a tick-box bureaucratic exercise and better focused on their own practice. But I think we need more time, in normal circumstances, to understand.

I suspect that with work that is now going on about post-registration training and education there is actually quite a lot of change that will feed into the way revalidation ought to work.

The Pharmaceutical Journal has covered ethnicity awarding gaps in the MPharm and the preregistration assessment. Is enough being done to look at this?

There’s no such thing as being finished with this kind of work. Each year, there is a clear disparity between people of different ethnic backgrounds in terms of the MPharm pass rate and the registration assessments.

Unless you can work out all the factors that actually impinge upon how well someone does in that exam, you’re not going to address the issue of whether there are particular things going badly wrong in the education or employment process. You’re not going to know whether you’re doing the right things to sort it out.

I’m not a great believer in edicts from the GPhC — you have to work with other people

You also have to bring everybody together talk about it. I’m not a great believer in edicts from the GPhC being issued for things like this; you have to work together with other people, agree there’s a problem, agree what the causal factors look like and what then needs to be done to try to stop that. There are a lot of people in that equation. I would expect that to carry on as a matter of priority.

The Professional Standards Authority said in February 2022 that the GPhC was lagging behind on the time taken to resolve some fitness-to-practise cases. What is being done to address this?

It’s not easy. You’re dealing with people who’ve raised concerns; you’re dealing with worried healthcare professionals about whom concerns have been raised. It’s perfectly clear that the longer a process is, the less fair it is to everybody involved: so it really is incumbent on us to try to sort out how to do that.

Some cases have delays built in because of third-party processes; for example, if the police or the Crown Prosecution Service are involved, we have to wait until they’ve completed what they’re doing.

Otherwise, it’s just simply a case of gathering the proper evidence in the first place and, of course, whether the GPhC should be involved at all.

Quite a lot of concerns that are raised with us are actually employment matters and not matters of fitness to practise. In those cases, it’s really persuading employers that, actually, their own processes are not working properly.

Should environmental sustainability be incorporated into the MPharm degree and/or GPhC inspection standards?

That’s a pair of very interesting ideas. There is definitely environmental concern around the amount of energy required in the production of medicines, but also the large quantity of medicines produced which are either not taken at all or are not taken right.

In September 2021, the overprescribing report from Keith Ridge, chief pharmaceutical officer for England, was a very good piece of work and there’s a lot for us to look at there in terms of how pharmacists’ standards address those issues. But an awful lot of it is about working more with the public and with patient groups about how to ensure that there is a better dialogue between patients and pharmacists to make sure that medicines are taken [in the right way] in the first place and ensure that any medicines that are not used can effectively come back into the system, if that is appropriate.

The increase in pharmacists in primary care will have a big impact on this — a pharmacist in a GP surgery will be able to address the whole issue of the practice’s prescribing record on particular conditions or drugs, and we may find much more efficient use of drugs through better prescribing as a result of that.

Reflecting on your eight years as chair, is there anything you regret?

I am sorry that I’ve not been able to make more progress on the issue of read/write access to patient records for pharmacists, which seems to me to be a public safety issue of a prime nature. Some of the reasons that people have given for not acting on that have not been very convincing.

There are some outstanding issues in online pharmacy

There are some outstanding issues in online pharmacy. It’s not our job to stand in the way of progress, but at the same time, we do have to understand when people are doing new things that they don’t overstep the mark. We’re still finding out quite a lot about some of the frankly less acceptable practices that have arisen in a small number of cases. But there have actually been enough of them to disrupt our fitness-to-practise work, because they’ve arisen in numbers having not been there before.

More broadly, I would have liked to have made more progress on public health in pharmacy. We get an awful lot of information from pharmacy inspections that tells us what good practice is and we should be disseminating that more widely than just in pharmacy. We ought to probably be briefing the health departments and the NHS in all three countries and saying to them: we are the regulator and we’re seeing good things.

What are you most proud of?

The revision of the standards [for pharmacy professionals, which came into effect in 2017], because that changed the whole way that the regulation of pharmacy actually operated. Also, the creation of the knowledge hub, starting to disseminate best practice in community pharmacy, and the refocusing of inspections on more targeted, intelligence-led inspections were important developments.

More recently, the initial education and training standards [introduced in 2021], because these are going to make pharmacy fit for the rapid changes that may be taking place in the health service as a whole.

And then there is work that’s just beginning on post-registration education and training. There are big fundamental changes here and I’m proud of the way that the GPhC managed to bring people together to do that work. It’s been a terrific example of teamwork.

What are your plans now you have stepped down as chair?

I’ve been doing regulation for 25 years now and I think everybody’s probably had enough of me! But I’ve been involved with pharmacists since 2008. I know a lot of them very well; I have a lot of admiration for a lot of the people and the teams involved in it.

It would be nice to think that one can make a more active contribution to the delivery side; into driving things forward in terms of the way public policy sees the contribution pharmacy could make.

We’ve got a good framework for it, now it’s a question of trying to make sure that it happens.