DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY / Raihana Asral / Shutterstock.com

Switching patients to new therapies is not always straightforward, but when it comes to anticoagulants it can be particularly complex. A lot of prescribers have to work closely with their patient to find the right anticoagulant for them because the side effects and potential risk of bleeding can be serious.

“[It’s] not as straightforward as switching a statin,” explains Katherine Stirling, consultant pharmacist in anticoagulation and thrombosis at St James University Hospital, Leeds.

“It needs to be done carefully, with the patient at the centre, if it’s appropriate for them to switch in the first place — because there are some patients it’s not appropriate for as well.”

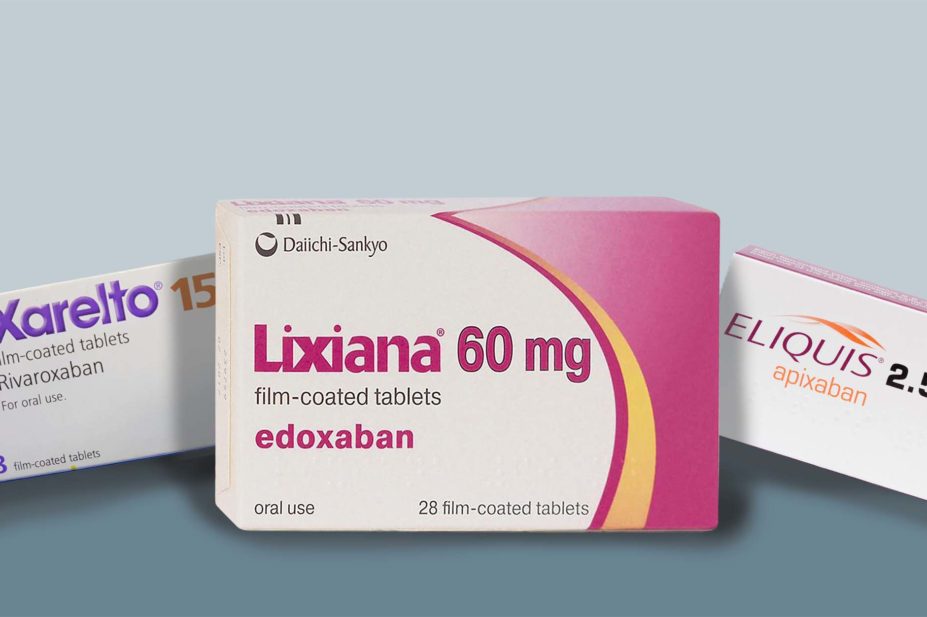

Nevertheless, the NHS in England is ploughing ahead with a national scheme to switch thousands of patients taking anticoagulants to edoxaban.

At the end of 2021, NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE&I) confirmed the details of a national procurement agreement for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

The letter, sent to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) across England, highlighted that Daiichi Sankyo, which manufactures the DOAC edoxaban under the brand name Lixiana, had offered better prices, investment and support than that offered individually or collectively by other DOAC suppliers.

This means edoxaban is now the DOAC with the lowest net acquisition cost by a significant margin. This cost, which is commercially confidential, is the listed tariff price minus any national discounts secured by NHSE&I.

As a result, commissioning recommendations were then published that encouraged prescribers to start new patients on edoxaban or, if locally agreed, switch DOAC patients to edoxaban, where clinically appropriate, and as a result of a shared decision making conversation[1].

Financial incentives

A few months later, in March 2022, three new indicators to be incentivised under the investment and impact fund (IIF) — which is used to support primary care networks in delivering high quality care to their patients — were announced by NHSE&I for 2022/2023[2]. One of these stated that GP practices would be rewarded for prescribing edoxaban to more patients from a pot of £14.8m.

Initially, NHSE&I set the lower and upper thresholds for the percentage of patients started or switched to edoxaban, in the six months to the reporting end date, to 40% and 60%, respectively. However, under updates to the 2022/2023 network contract published on 31 March 2022, these thresholds were reduced to 25% and 35%, respectively, much to the relief of some clinicians.

But even now, incentives around edoxaban are still dividing prescribers.

In June 2022, a joint position statement from Oxfordshire, Berkshire West and Buckinghamshire clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) said they had “decided not to act” on commissioning recommendations from NHSE&I regarding prescribing edoxaban in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF)[3].

In the statement, the CCGs said that currently there were no head-to-head clinical trials to give “definitive guidance” on which DOAC was best for AF and, therefore, existing patients must not be “batch switched” to edoxaban. Instead, the statement said that consideration for a switch must be made on an individual patient basis, as per guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), published in 2021[4].

No antidote

Edoxaban does offer some other advantages over other DOACs. For example, it is taken as a once-daily dose and can be taken on a full or empty stomach, unlike DOACs such as apixaban and dabigatran, which are taken twice a day, or rivaroxaban, which has to be taken with food.

However, as highlighted in Oxfordshire, Berkshire West and Buckinghamshire CCGs’ joint statement, there are instances when edoxaban may not be suitable; for example, in obese patients with a body mass index of over 40 or in patients with a high creatinine clearance[3].

You want people to be confident in their healthcare providers that they’re offering them appropriate advice and taking their wants and needs into account

Katherine Stirling, consultant pharmacist in anticoagulation and thrombosis at St James University Hospital, Leeds

“There’s less evidence for bigger people — patients over 120kg,” explains Stirling, adding that there was also a concern from the original studies that in patients with really good renal function — creatinine clearance over 95mL/min — edoxaban may have reduced efficacy.

There is also no licensed antidote for edoxaban, which may put off certain patients from being switched because it means there is not a straightforward solution if they experience serious and uncontrolled bleeding — a potential risk of being on a DOAC.

“It’s the only [DOAC] without a licensed antidote,” says Stirling.

“There is good evidence for prothrombin complex concentrate for management of bleeding, [but] for andexanet, which is licensed for apixaban and rivaroxaban, there weren’t enough edoxaban patients in the study so it doesn’t have a licence or NICE approval.”

Difficult consultations

As a result, clinicians may need to prepare to have some challenging conversations with their patients. Nonetheless, these are conversations that need to happen, preferably face to face. This communication is particularly important in this case because the switching decisions are being based mostly on cost, something patients could take issue with.

“You want people to be confident in their healthcare providers that they’re offering them appropriate advice and taking their wants and needs into account,” says Stirling.

“It needs to be done really carefully with patient involvement,” she adds.

“These drugs aren’t the safest group in terms of what could go wrong … if you switch somebody and then they bleed … the risk could be high if it’s not done carefully.”

Charlotte Nicholls, head of policy and influencing at the Stroke Association, agrees that it is important for patients to be a part of any discussions around changes to their medication.

“We want patients with AF to continue to be reviewed at least annually and to be part of discussions about any changes in their anticoagulant medication,” she adds.

“Everyone with AF at risk of stroke deserves to lead the best life possible. That includes empowering patients to take control of their health and to be involved in discussions with their GP or health professional about optimal treatment options.”

For Matthew Fay, a GP with a special interest in cardiology, the new IIF indicators do not present any “significant issues” to his practice but this is likely to be because he is the clinical lead for a “very robust” anticoagulation service within which edoxaban is already widely prescribed to patients.

“Our first-line DOAC has been edoxaban as it has the lowest acquisition cost for the NHS, and this has been true for some years. In line with the General Medical Council good practice, we should endeavour to practise cost-effective medicine and we felt the evidence supported the use of edoxaban,” he explains.

“If we had not had high use of edoxaban then we could have considered a transfer to edoxaban (at review appointment if dose adjustment was required, for instance) but this would have been inside a very experienced team, led by a clinician with a rich knowledge of all these agents.”

If I was a national leader or key opinion leader in NHS policy, I may have highlighted the significant risk with a medication ‘switch’ within DOACs

Matthew Fay, a GP with a special interest in cardiology

Fay does acknowledge, however, that not all DOAC prescribers have the luxury of working within such an expert team.

“If I was a national leader or key opinion leader in NHS policy, I may have highlighted the significant risk with a medication ‘switch’ within DOACs — these are not as simple as statins. However … I am pleased to say these are discussions outside my pay grade.”

Stirling agrees that not all prescribers are confident when it comes to anticoagulation.

“Primary care pharmacists are often quite new and don’t feel confident with anticoagulation … is the GP going to do it? Who is going to have that discussion? It needs a bit more thought and time with patients to do it, so actually it is quite time consuming.”

She adds that a lot of her and her colleagues’ concerns stem from the fact that not all areas have as good a working relationship with their pharmacy team as they do in her patch, and many are more preoccupied with the potential savings associated with switching than ensuring the switching is done in the best way. In some areas, patients have been notified of their switch via mail.

“We’ve spent quite a lot of time with patients trying to get the right drugs … to have all that undone with a letter.” she says.

Lack of guidance

To complicate matters further, at the beginning of June 2022, Teva UK launched a generic version of apixaban which, with a total cost of more than £388m in 2021, was the most costly drug to the NHS[5].

Previously there was only a branded product available, manufactured by Pfizer, but by successfully invalidating the apixaban patent in the UK High Court, Teva UK was able to launch its own generic version.

The availability of generic apixaban will offer the NHS considerable savings and the news could impact on prescribers’ willingness to follow along with the IIF indicators.

“There will be considerable time before a change in the drug tariff, while the cost saving for edoxaban is here now,” says Fay.

“It will, however, derail the IIF … as people will be concerned that they will do work with edoxaban and then be asked to redo it all again with apixaban, a little like the back and forth with simvastatin and atorvastatin in the 2000s.”

Lynne Garforth, a pharmacist and director at Ashburton Prescribing, a prescribing support service, says that she has not seen any plans to deviate from adhering to the edoxaban recommendations across her patch in Merseyside and Lancashire.

There still seems to be a real focus on carrying out the DOAC switch element of the commissioning recommendation … the emergence of generic apixaban has not impacted on this … which surprises me somewhat

Lynne Garforth, a pharmacist and director at Ashburton Prescribing

“There still seems to be a real focus on carrying out the DOAC switch element of the commissioning recommendation … the emergence of generic apixaban has not impacted on this it would seem, which surprises me somewhat.”

Garforth says that while there is an IIF target to increase the prescribing of edoxaban, there are other opportunities to do this. These include instead using the considerable amount of the medicine management team or primary care network pharmacist’s time to carry out switches for patients taking vitamin K antagonists to DOACs as per NICE recommendations, or for reviewing patients with known AF who are not being prescribed an anticoagulant.

“In both cases, using edoxaban first line where possible rather than focusing efforts on switching patients who are already on a suitable treatment to hit this target.

“Especially now that there is a generic version of apixaban available and more may also come on to the market in the not-too-distant future.”

The Primary Care Cardiovascular Society, Primary Care Pharmacy Association and UK Clinical Pharmacy Association have now published national guidance on implementation of the NHSE DOAC commissioning recommendations, including first-line use of edoxaban, warfarin to DOAC switching and DOAC to edoxaban switching, but, given the incentives have been in place since March 2022, many practices will have already started the switching process, keen to benefit from the financial incentives on offer (see Figure).

Although with all this work underway, there may be good reason to worry that, by 2023, they could be doing this all over again with generic apixaban.

NHSE&I were approached for comment but did not provide one in time for publication.

- This article was amended on 1 August 2022 to clarify that DOAC patients may be switched to edoxaban if locally agreed, in addition to where clinically appropriate and as a result of a shared decision making conversation, and that national guidance on implementation of NHS England’s DOAC commissioning recommendations was produced by the Primary Care Cardiovascular Society, Primary Care Pharmacy Association and UK Clinical Pharmacy Association

- 1Operational note: Commissioning recommendations for national procurement for DOACs. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/B1279-national-procurement-for-DOACs-commissioning-recommendations-v1.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2022).

- 2Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service Investment and Impact Fund 2022/23: Updated Guidance March 2022. NHS England . 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/B1357-investment-and-impact-fund-2022-23-updated-guidance-march-2022.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2022).

- 3JAPC Position Statement on Edoxaban (Lixiana®) prescribing for non-valvular atrial fibrillation only. Area Prescribing Committee Oxfordshire (APCO) Buckinghamshire Medicines Value Group (MVG) Berkshire West Prescribing Oversight Committee (POC). 2022.https://clinox.info/clinical-support/local-pathways-and-guidelines/Clinical%20Guidelines/BOB%20Edoxaban%20statement.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2022).

- 4Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196 (accessed 21 Jul 2022).

- 5Prescription Cost Analysis – England – 2021/22. NHS Business Services Authority . 2022.https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/prescription-cost-analysis-england/prescription-cost-analysis-england-202122 (accessed 21 Jul 2022).

3 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Quote from email message sent to PCN Clinical Directors and PCN Lead Pharmacists from Medicines Value Team NHSEI on 7th July 2022:

'Neither the price at which the generic version of apixaban has been made available nor its limited supply justifies the NHS to change the existing commissioning recommendations that were issued in January 2022 and therefore, consistent with NICE guidance, we continue to recommend clinicians use edoxaban for new patients, where clinically appropriate.'

Concern re suitability of edoxaban for patients with CrCl > 95ml/min;

‘On the other side of the spectrum, a possibly decreased efficacy

of edoxaban 60 mg OD compared with warfarin was observed in

patients with a CrCl of >95 mL/min.31 Interestingly, as a result of

these findings, further post hoc analyses revealed a similar effect

also for Rivaroxaban188 and Apixaban.189’

from

The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation’

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/39/16/1330/4942493

Obese patients. ISTH guidance is that unsuitability of DOACs in patients with BMI >40 weight >120kg applies to ALL DOACs:

see:

Martin, K., Beyer-Westendorf, J., Davidson, B.L., Huisman, M.V., Sandset, P.M. and Moll, S., 2016. Use of the direct oral anticoagulants in obese patients: guidance from the SSC

of the ISTH. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 14(6), pp.1308-1313.