Shutterstock.com

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Understand how pharmacy practice both contributes to the climate crisis and is vulnerable to its effects;

- Describe the principles of sustainable healthcare in relation to pharmacy practice;

- Give examples of how pharmacy teams can apply the principles of sustainable healthcare to routine pharmacy practice.

The earth is heating owing to the emission of greenhouse gases caused by human activity, including unsustainable energy use, land use and consumption1. The consequences of this global heating include increasing frequency and severity of heatwaves, wildfires, drought, floods and storms; however, we may not associate provision of healthcare with this changing climate, nor recognise the health-related impacts of climate change2.

The climate crisis negatively impacts the population’s health and wellbeing and adds to the burden on the health service in several ways3,4. In the UK, one in three flood victims experience long-term mental health problems, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder5. Extreme heat in 2022 was associated with an additional 3,000 deaths in the UK3. Air pollution negatively affects health at every stage of life and is associated with up to 40,000 deaths annually in the UK6. Poor air quality is also associated with emergency asthma admissions7. The health impacts of climate change are exacerbated by rising health and social inequality, with the most deprived suffering the worst consequences4,8.

Healthcare services are vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis. Global extreme weather events create pressure on complex supply chains, including pharmaceuticals, exacerbating existing medicine supply problems9. Locally, extreme weather (both heat and flooding) present challenges within the day-to-day running of health services, impacting storage of medicines, operation of equipment and IT, maintenance of a healthy working environment and access to healthcare sites. The vast majority (90%) of NHS hospitals are at risk of overheating and 10% are at risk of flooding10,11.

Sustainable healthcare has been defined as “the ability to provide healthcare to meet the needs of this generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their healthcare needs”12.

This article defines the relationship between health and climate. It introduces the principles of sustainable healthcare and explores how they can be applied to pharmacy practice.

Provision of healthcare contributes to the climate crisis

The NHS is responsible for 4-5% of the UK’s carbon footprint (see Figure 1)13. Of this, pharmaceuticals, inhalers and anaesthetics account for a quarter of the entire NHS carbon footprint13. Pharmaceuticals also present a significant challenge in terms of pharmaceutical pollution of waterways and plastic pollution from packaging and disposable devices14.

These negative health impacts place an ethical and professional responsibility on us as healthcare professionals to minimise our contribution to the climate and ecological crises15,16. The NHS is legally bound by the 2022 Health and Care Act to meet its target to be net zero by 2045, with an ambition to reach an 80% reduction by 2036 to 203913. In August 2024, the General Pharmaceutical Council published its ‘Net zero action plan for sustainable pharmacy regulation‘, which is aims to achieve carbon net zero 2040 for the organisation and sets out plans to embed environmental sustainability at every level of pharmacy regulation17. In February 2024, the Care Quality Commission has introduced a requirement to address environmental sustainability within their single assessment framework via the quality statement on environmental sustainability18. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s ‘Competency framework for all prescribers’, published in September 2021, asks prescribers to “consider the impact of prescribing on sustainability, as well as methods of reducing the carbon footprint and environmental impact of any medicine”19.

Pharmacy teams have a significant role to play in encouraging healthy living, streamlining prescribing processes, ensuring appropriate and sustainable use of medicines, avoidance of waste, and facilitating appropriate disposal of medicines to minimise their negative impact on the environment16. Pharmacy teams already undertake much of this work as routine practice but may not recognise the significance of this work in relation to sustainability. The principles of sustainable healthcare enable us to view practice through the lens of sustainability20.

The principles of sustainable healthcare

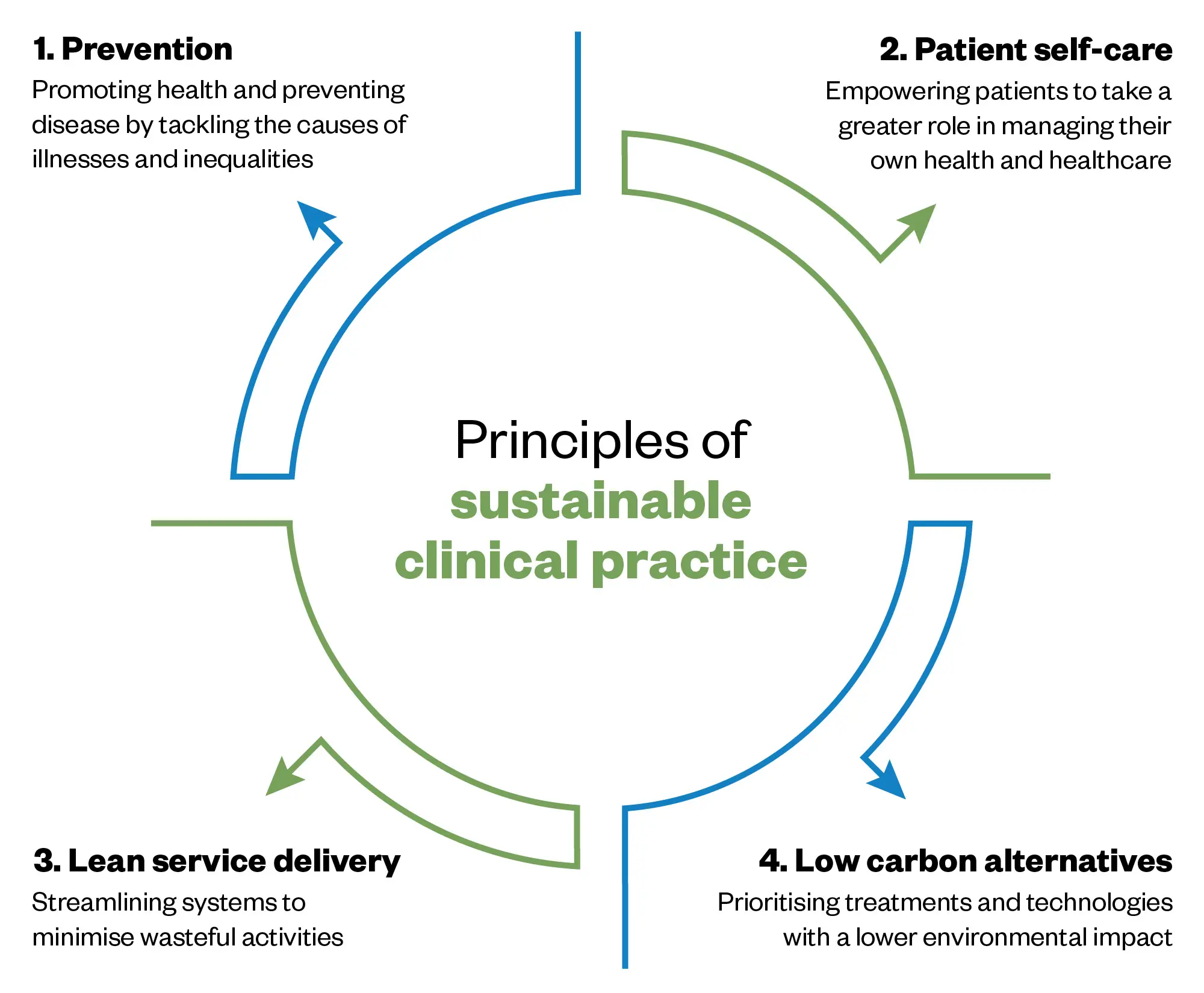

In response to these challenges, the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare (CSH) developed the Principles of Sustainable Clinical Practice to enable health services to identify, prioritise and implement actions that drive sustainable clinical transformation (see Figure 2)20. Applicable across any sector of healthcare, the principles are listed in order of their impact and importance in optimising the sustainability of clinical practice.

Adapted from Centre For Sustainable Healthcare

These principles were further developed to encompass non-clinical activity within sustainable healthcare by including a fifth principle that addresses sustainable resource use. These five principles are shown in the form of a driver diagram in Figure 321. By considering the different drivers that lead to emissions and resource use, practitioners can start to identify change ideas designed to reduce carbon while delivering high-quality care. To see examples of pharmacy-related change ideas, click on the empty boxes in the diagram. Note that many ideas will align to more than one principle. There are many examples of practice that demonstrate the wide-ranging positive impacts of a sustainable approach, improving clinical and population health outcomes, while minimising environmental impacts, optimising social value and reducing costs.

Driver diagram templates are available on the SusQI website.

To support the implantation of change ideas, the SusQI framework has been developed to support the adoption of sustainability into routine quality improvement22. Examples of sustainable quality improvement are provided in the sections below.

Prevention

Prevention is the first and most impactful principle of sustainable healthcare. If we can prevent disease from occurring in the first place, this benefits the patient’s health and wellbeing, but also eliminates the carbon footprint of healthcare activity that would be required to manage that disease. It also avoids the cost and burden placed on NHS services. Similar impacts can be achieved by reducing progression of disease and avoiding exacerbations of disease and admission to inpatient settings where resource use and associated emissions are highest.

The current health of the UK illustrates that more can be done to prevent disease23. In May 2024, a report published by the Department of Health and Social Care highlights that healthcare demand is at an all-time high and is set to increase as the population ages and health needs become increasingly numerous and complex24,25. Six conditions — cancer, heart disease, musculoskeletal disorders, mental ill-health, dementia and respiratory diseases — all of which are caused or exacerbated by lifestyle factors, account for 60% of ill health and early death in England26. Applying evidence-based preventative interventions has been estimated to add 20 more healthy days per person, per year, in the UK — a 33% reduction in ill health24.

There is a need to normalise prevention and to make positive lifestyle choices in relation to diet and physical activity easy and accessible to everyone24,27. Evidenced-based interventions on diet and physical activity to improve health and avoid disease can also have positive impacts on climate change. Limiting consumption of meat, particularly red meat and processed meat, which are known carcinogens, and increasing the proportion of whole food plants (fruit, vegetables, wholegrains, legumes, nuts, seeds) has proven health benefits in reducing the incidence of a range of conditions, including obesity, heart disease, diabetes and some cancers28–30. It also enables us to reduce the amount of land and water use dedicated to food production while continuing to produce sufficient food for the world’s growing population31.

The health benefits of physical activity are well documented and can also have a positive impact on climate change27. For example, individuals undertaking physical activity in place of using a car reduce their carbon footprint, contribute to a reduction in local air pollution and are likely to be increasing their time outside in green space, which is also known to be beneficial for mental health6,32,33.

Pharmacy teams already engage effectively in a wide range of preventative activities, including vaccination, screening for conditions such as hypertension and providing healthy living advice34. Pharmacy teams will be familiar with using the ‘Making every contact count’ approach to address harmful behaviour, such as smoking35. More emphasis now needs to be given to using an informed and evidenced-based approach to recommending dietary changes and increased physical activity for disease avoidance in the general population23.

Prevention activities should now be targeted so that people are able to benefit before the point at which medication is indicated. For example, women attending for HRT prescriptions can be advised to take preventative action against osteoporosis by undertaking weight-bearing exercise and ensuring they have sufficient calcium in their diet36. The positive impact of improved diet, physical activity and mental health and wellbeing should be emphasised, ensuring that patients understand the potential that lifestyle change has to slow or reverse the progression of disease and reduce exacerbations24,26,27,30–33. We can work more closely with colleagues such as social prescribers to enable patients to live healthily for longer.

Patient empowerment

Closely linked to prevention, patient empowerment enables patients to take a more active role in managing their own health and health conditions. An engaged, informed and supported patient is more likely to undertake self-care and self-monitoring when their condition is stable and to access healthcare services appropriately when needed, as demonstrated by the appropriate use of asthma self-management plans37. Additional information on the significance of patient empowerment can be found in ‘Principles of person-centred practice for prescribing’.

Evidence suggests that improvements can be made in decisions around medicines. Modern western lifestyle and culture is contributing to poor health outcomes for many people24–30. The medical model and ever-increasing levels of prescribing is proving to be neither sustainable nor effective38–41. It has been estimated that £300m worth of medication goes unused annually in England and up to half of all medicines prescribed for long-term conditions are not taken as recommended42–44. Medicines optimisation is an important responsibility for pharmacy teams and is one area where positive outcomes can be achieved for patients, NHS services and the environment. There are already some initiatives that have been started to improve this.

For example, in Gloucestershire, patients are encouraged to check their medicines before they leave the pharmacy so that any unwanted medicines can be returned for re-use45.

In its Kapsule Kids project, Great Ormond Street Hospital used Kidzmed training to empower paediatric patients to take tablets or capsules instead of liquids. The initial project generated savings of £258,255 and saved the carbon equivalent of driving 972 miles in an average car. Pills are likely to have a reduced environmental impact compared with an equivalent dose of liquid medication, with less packaging and less wasted medicine46.

Lean pathways

Streamlining systems — such as repeat prescribing — reducing waste of medicines, high-risk drug monitoring (aligning blood tests to minimise visits and use of consumables) and undertaking remote consultations where appropriate are all part of typical day-to-day practice for many pharmacy teams. These activities not only reduce cost and carbon emissions, but also streamline services and minimise the risk of avoidable harm from unnecessary interventions, prescribing and investigations. While the efficiency gains and patient benefits of more streamlined care are obvious, the environmental sustainability impacts are less commonly considered.

Medicines, including inhalers and anaesthetics, account for 25% of the NHS carbon budget, representing a ‘carbon hotspot’ that needs to be addressed13. Prescribing is the most common intervention in the NHS. In the 2022/2023 financial year, 1.37 billion prescription items were dispensed in the community in England, Scotland and Wales, at a cost of £12.3bn38–40. The National Overprescribing Report, published in September 2021, revealed that at least 10% of prescription items in primary care need not have been issued. Medicines waste costs the NHS at least £300m per year42,43.

This represents significant waste of limited NHS resources and has widespread environmental impacts, including the energy and emissions involved in the development, manufacture, transport and use of medicines that have not been used; packaging waste (often single use plastic or difficult to recycle materials) and the risk of pharmaceutical pollution of waterways14. Interventions to reduce unnecessary prescribing, undertake appropriate deprescribing and minimise medicines waste could have significant impacts in reducing the environmental impact of medicines use.

For more on this topic, listen the episode of the PJ Pod: ‘Effective deprescribing: getting the most from medicine’.

The NHS Dorset ‘Medicines waste’ campaign empowered patients to contribute to streamlining the repeat prescription process by only ordering the medicines that they need, resulting in a 2% drop in prescription requests across Dorset. In the first two months, approximately 65,000 prescription items were not requested because of the campaign, with associated savings of £475,000 in avoided prescription costs and 294,975kg of avoided carbon emissions47. There are many examples of SusQI projects that illustrate a range of interventions that have been undertaken for cost or efficiency reasons but have resulted in significant carbon savings (see Box 1 for links to case study examples).

Box 1: SusQI projects that have resulted in carbon savings

Deprescribing

Reducing unnecessary dosing with proton pump inhibitors in critical care patients through improved staff education, patient information and enhanced review processes.

Reducing paracetamol co-prescribing with strong opioids on the Sheffield Macmillan Unit

Utilising PRN versus regular prescribing of paracetamol on a palliative care unit to reduce tablet burden and wasted medication.

Streamlining blood requests

SusQI case study: Reducing routine blood testing in frailty and care of the elderly wards

Reducing low-value and unnecessary blood testing on a care of the older person’s ward through use of a decision-making tool on the need for blood testing.

Reducing medicines waste in hospitals

Reducing medicines waste by avoiding disposal of patient’s own drugs during inpatient stays through staff education and improved medicines waste segregation processes.

Streamlining operating theatres’ stock medicines to reduce waste, avoid over-stocking and improve efficiency.

‘Scheme to reuse medicines in hospital cuts carbon emissions and saves money‘, The Pharmaceutical Journal, and ‘Reducing Medicine waste by returning unused medicines to pharmacy‘, Pharmacy Sustainability Network

Reducing medicines waste by ensuring patients own medicines move with them during hospital stay and optimising re-use of hospital medicines.

Procurement

‘Tackling pharmacy’s reliance on single-use plastic‘, The Pharmaceutical Journal

Reducing single use plastic bags in hospital pharmacy.

More can be found on the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare Networks website.

Low-carbon alternatives

Low-carbon alternatives are products or processes that emit minimal greenhouse gases. Metered dose inhalers (MDIs) and anaesthetic gases are two carbon hotspots, emitting high levels of greenhouse gases though their direct use13. While there are alternatives and strategies that can be considered to reduce the use of both, it should be noted that a blanket approach for inhaler switching is not appropriate.

For patients that use inhalers, a holistic person-centred approach that focuses on informed self-management, minimising exacerbations, optimising inhaled treatment and engaging in self-care, such as regular physical activity, will be more impactful in reducing the carbon footprint of that patient’s treatment through avoided exacerbations and admissions than could be achieved by simply switching to a low-carbon inhaler48. It has been estimated that poorly controlled asthma generates three times the carbon footprint of well-controlled asthma48.

However, MDIs represent 3% of the overall NHS carbon footprint13. MDI propellant greenhouse gases are released each time the metered dose is used and if the inhaler is disposed of inappropriately49. It is therefore essential that pharmacy teams are aware of the relative carbon footprint of inhalers and can contribute to high-quality, low-carbon respiratory care49,50.

Pharmacy teams should be aware of the different terminology used to describe inhalers; it should be noted that carbon neutral inhalers are not necessarily low carbon. Carbon neutral status can be obtained by buying carbon emissions offsets for avoided emissions in developing countries, rather than eliminating emissions or paying for removed emissions51. In the case of carbon neutral inhalers, this does nothing to reduce the carbon footprint of the NHS. Greenhouse gases will still be released when the inhalers are used. Dry powder inhalers contain no propellant and are therefore the lowest carbon footprint inhalers available49. There are many examples of initiatives to reduce the carbon footprint of respiratory care, including addressing excessive salbutamol use, optimising treatment according to current guidelines (early use of inhaled corticosteroids and ensuring that patients are using an inhaler that suits their intuitive breathing technique, see Box 2)52.

Box 2: Examples of initiatives to reduce the carbon footprint of respiratory care

Patients using six or more short-acting beta-2 agonist (SABA) inhalers per year were pro-actively identified and offered asthma reviews to optimise asthma care; minimise carbon footprint of inhalers; educate patients to reduce over ordering; educate patients to return used/unwanted inhalers to pharmacies.

SusQI case study: Hywel Dda medicines optimisation team, “reducing the inhaler blues”

This project involved identification of patients at high risk of asthma exacerbation (more than 12 SABA inhalers/year, oral steroids in the past 6 months for respiratory exacerbation or prescribed SABA inhaler alone with no inhaled corticosteroids) and offering face-to-face respiratory reviews to optimise asthma care and reduce inhaler carbon footprint where possible.

A project focused on improving staff and patient education to:

- Avoid issuing duplicate inhalers to patients attending for assessment who already have an inhaler;

- Ensure use of low carbon inhalers where appropriate;

- Educate patients and parents on number of doses per inhaler and returning unwanted and used inhalers to the pharmacy.

Anaesthetics represent a further 2% of the overall NHS carbon footprint. Desflurane has been decommissioned by the NHS and replaced with the lower carbon emitting and clinically equivalent sevoflurane53. Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas. The traditional manifold systems have been found to be highly inefficient, with up to 95% leakage of nitrous oxide from the pipes54. Work is underway around the UK to address this waste54,55.

Pharmacy teams should be aware of other low carbon alternatives, such as formulation considerations (switching IV to oral or liquids to tablets), reusable devices and non-pharmacological options, such as green prescribing and social prescribing46,56.

Box 3: Examples of use of low-carbon alternatives

SusQI case study: Improving the environmental impact of patients with diabetes and on insulin

A project focused on increasing the use of reusable insulin pens where appropriate and promoting the use of recycling schemes for single use insulin pens.

‘How Louise discovered walking was a natural pain reliever’

Active Devon is a community-focused, non-profit organisation with a vision of everyone in Devon active for life. Their mission is to unlock the ability of movement to change lives for the better. This video illustrates the use of green prescribing (walking groups) to manage pain, reduce the need for opioid analgesia and support weight loss through physical activity.

Operational resource use

Sustainable resource use focuses first on minimising resource use as much as possible and then ensuring that resource is used as sustainably as possible and reused or repurposed before recycling or disposal is considered. The aim is to minimise consumption, access renewable energy and promote the circular use of products.

Several recycling schemes are in operation for medicines devices and packaging in the UK. These include inhaler recycling schemes in Kent and Medway and South East London57; recycling schemes for insulin pens, such as Re-Pen and Pencycle; and recycling of brand-specific plastic syringes and spoons.

Several high street pharmacies now provide medicines blister pack recycling collection boxes in some parts of the UK. While recycling is better than disposal and, in the case of inhalers, ensures that greenhouse gases are captured for reuse, NHS waste accounts for only 0.1% of the NHS carbon footprint58. Reduction of consumption, where appropriate, is a much more effective intervention.

In pharmacy settings, sustainable resource use might include simple interventions, such as employing a switch-off checklist at the end of the day to ensure that lights, equipment, heating etc are turned off, switching to LED lighting, or streamlining deliveries to reduce the number of journeys and fuel consumption59. Energy use can be addressed by switching utility provider and using a tariff backed by renewable energy production or investing directly in renewable energy through adoption of solar panels or heat pumps. It may also be possible to undertake actions to conserve energy use and consumption of consumables such as paper, single use plastic and PPE.

There are a range of recommendations available from SEE sustainability and the Green Impact for Health Toolkit59,60. In May 2023, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society announced that it was launching its ‘Greener pharmacy toolkit‘, which provides a checklist of initiatives for community pharmacies and hospital pharmacies to consider.

Some examples of sustainable resource use initiatives can be seen in Box 4.

Box 4: Examples of sustainable resource use initiatives

Medicines delivery

Drone deliveries of vital chemotherapy to the Isle of Wight

Use of electric drones to deliver chemotherapy to patients on the Isle of Wight, reducing a 4-hour journey by road and sea to a 30-minute flight, saving carbon emissions, reducing air pollution and improving efficiency.

Green transport delivers life-saving drugs and improves patient experience

Use of bicycle couriers instead of vans to deliver chemotherapy to two sites in Oxford, saving time and money and reducing air pollution.

Energy

Elective theatre end-of-day shut down

Education of staff and development of a theatre shut-down list to effect behaviour change to switch off equipment at the end of the day, resulting in cost and carbon savings and improved staff satisfaction.

Signposting

Climate and Health

All Our Health — e-learning for healthcare: climate change and air pollution modules

Environmentally Sustainable Healthcare: e-learning for healthcare

Prevention

Plant-Based Health Professionals UK: a community interest company dedicated to providing education and advocacy on whole food plant-based nutrition and lifestyle medicine for prevention and treatment of chronic disease

British Society of Lifestyle Medicine — What is lifestyle medicine?

Medicines Optimisation

PrescQIPP — Bulletin 340: Sustainability in medicines optimisation

PrescQIPP — Bulletin 295: Inhaler carbon footprint

NHS England — National medicines optimisation opportunities 2023/2024

Networks

Pharmacy Sustainability Network: Sustainable Healthcare Networks Hub

Pharmacy Declares: climate conscious pharmacy professionals based in the UK

Primary Care Pharmacy Association (PCPA) — Greener PCPA

Greener Practice: UK primary care sustainability network

Case Studies

Sustainable Healthcare Networks Hub — Resource library

Sustainable practice: what can I do?: Series published by The BMJ aimed to offer tangible actions clinicians can take to reduce the carbon footprint of healthcare

System progress: a collection of case studies highlighting sustainability work happening at all levels across the NHS

Greener NHS Knowledge Hub: FutureNHS Collaboration Platform (NHS registration required)

Centre for Sustainable Healthcare

Sustainable Quality Improvement

Centre for Sustainable Healthcare — Courses

Centre for Sustainable Healthcare — Newsletter

- 1.Synthesis Report of the Sixth Assessment Report. IPCC. 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.ipcc.ch/ar6-syr/

- 2.Going green; what do the public think about the NHS and climate change? . The Health Foundation. October 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/going-green-what-do-the-public-think-about-the-nhs-and-climate-change

- 3.Climate change: health effects in the UK. UK Health Security Agency. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/climate-change-health-effects-in-the-uk

- 4.The Lancet countdown report. Lancet Commission. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.lancetcountdown.org/2023-report/

- 5.The impacts of climate change on public health. The Climate Coalition. 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.theclimatecoalition.org/health-report

- 6.Whitty C. Chief Medical Officer’s annual report: air pollution report. Department of Health and Social Care. 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annual-report-2022-air-pollution

- 7.Singh A, Morley GL, Coignet C, et al. Impacts of ambient air quality on acute asthma hospital admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Oxford City, UK: a time-series study. BMJ Open. 2024;14(1):e070704. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070704

- 8.Health Equity in England; the Marmot report 10 years on. The Health Foundation. 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on

- 9.Climate risk to UK supply chains: the role of government and business. Climate Change Committee. 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://www.theccc.org.uk/2022/10/20/climate-risk-to-uk-supply-chains-the-roles-of-government-and-business/

- 10.Jeffrey J. NHS Overheating. Analysis on the impact of heat waves on people who rely on and work in the NHS. Round Our Way. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.roundourway.org/our-impact/nhs-overheating

- 11.Jeffrey J. NHS Underwater. Analysis of increasing flooding events in the NHS and its impact on patients. Round Our Way. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.roundourway.org/our-impact/nhs-underwater

- 12.Environmentally sustainable health systems: a strategic document. World Health Organization. 2017. Accessed October 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/340375/WHO-EURO-2017-2241-41996-57723-eng.pdf?sequence=3

- 13.Delivering a Net Zero NHS. NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2020/10/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service.pdf

- 14.Pharmaceutical residues in freshwater. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2019. Accessed October 2024. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/pharmaceutical-residues-in-freshwater_c936f42d-en

- 15.Yassaie R, Brooks L. Reassessing ‘good’ medical practice and the climate crisis. J Med Ethics. Published online June 13, 2024:jme-2023-109713. doi:10.1136/jme-2023-109713

- 16.Pharmacy’s role in climate action and sustainable healthcare. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/all-our-campaigns/policy-a-z/pharmacys-role-in-climate-action-and-sustainable-healthcare

- 17.Carbon Net Zero Action Plan. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/about-us/publications-and-insights/carbon-net-zero-sustainability-action-plan

- 18.Environmental sustainability – sustainable development. Care Quality Commission. 2024. https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-regulation/providers/assessment/single-assessment-framework/well-led/environmental-sustainability

- 19.A Competency framework for all prescribers. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks/prescribing-competency-framework/competency-framework

- 20.Mortimer F. The sustainable physician. Clinical Medicine. 2010;10(2):110-111. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.10-2-110

- 21.Driver Diagram template. SusQI project. https://www.susqi.org/templates

- 22.Mortimer F, Isherwood J, Wilkinson A, Vaux E. Sustainability in quality improvement: redefining value. Future Healthcare Journal. 2018;5(2):88-93. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.5-2-88

- 23.Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. The Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791-846. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32822-8

- 24.Deanfield J. Making prevention everyone’s business: a transformational approach to personalised prevention in England. Department of Health and Social Care. May 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/making-prevention-everyones-business

- 25.Health in 2024: projected patterns of illness in England. The Health Foundation. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/health-in-2040

- 26.Major conditions strategy: case for change and our strategic framework. Department of Health and Social Care. 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/major-conditions-strategy-case-for-change-and-our-strategic-framework/major-conditions-strategy-case-for-change-and-our-strategic-framework–2

- 27.All Our Health: personalised care and population . Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/all-our-health-personalised-care-and-population-health

- 28.Brown KF, Rumgay H, Dunlop C, et al. The fraction of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 2015. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(8):1130-1141. doi:10.1038/s41416-018-0029-6

- 29.Red Meat and Processed Meat. Vol 114. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. Accessed October 2024. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Red-Meat-And-Processed-Meat-2018

- 30.Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958-1972. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30041-8

- 31.The EAT-Lancet Commission Summary Report. EAT-Lancet Commission. Accessed October 2024. https://eatforum.org/eat-lancet-commission/eat-lancet-commission-summary-report/

- 32.Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environmental Research. 2018;166:628-637. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.030

- 33.Green and Blue Spaces and Mental Health. World Health Organization. 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/342931/9789289055666-eng.pdf

- 34.NG102: Community pharmacies: promoting health and wellbeing. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2018. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng102

- 35.Making every contact count consensus statement. Public Health England. 2016. Accessed October 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/making-every-contact-count.pdf

- 36.Bone health for all. Royal Osteoporosis Society. Accessed October 2024. https://theros.org.uk/information-and-support/bone-health

- 37.Pinnock H, Parke HL, et al. Systematic meta-review of supported self-management for asthma: a healthcare perspective. BMC Med. 2017;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0823-7

- 38.Prescription cost analysis, England. NHS Business Services Authority. June 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/prescription-cost-analysis-england/prescription-cost-analysis-england-202324

- 39.Dispenser payments and prescription cost analysis. Public Health Scotland. September 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/dispenser-payments-and-prescription-cost-analysis/dispenser-payments-and-prescription-cost-analysis-financial-year-2022-to-2023

- 40.Primary care prescriptions. Welsh Government. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.wales/primary-care-prescriptions-april-2022-march-2023-html

- 41.Busfield J. ‘A pill for every ill’: Explaining the expansion in medicine use. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(6):934-941. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.068

- 42.National overprescribing report: Good for you, good for us, good for everybody. Department of Health and Social Care. September 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-overprescribing-review-report

- 43.Evaluation of the Scale, Causes and Costs of Waste Medicines. York Health Economics Consortium and School of Pharmacy University of London. 2010. Accessed October 2024. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1350234/1/Evaluation_of_NHS_Medicines_Waste__web_publication_version.pdf

- 44.Barber N. Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditions. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13(3):172-175. doi:10.1136/qshc.2003.005926

- 45.Gloucestershire Primary Care Networks are working to improve their green credentials. NHS Gloucestershire. April 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nhsglos.nhs.uk/news/gloucestershire-primary-care-networks-are-working-to-improve-their-green-credentials

- 46.Lim E, Parker E, Vasey N. Why learning how to swallow pills is good for patients, parents, and the planet. BMJ. Published online January 9, 2024:e076257. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076257

- 47.“Only order what you need” medicines waste campaign. NHS Dorset. Accessed October 2024. https://nhsdorset.nhs.uk/health/medicines/waste/

- 48.Wilkinson AJK, Maslova E, Janson C, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions associated with suboptimal asthma care in the UK: the SABINA healthCARe-Based envirONmental cost of treatment (CARBON) study. Thorax. 2024;79(5):412-421. doi:10.1136/thorax-2023-220259

- 49.Inhaler carbon footprint. PrescQIPP. 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.prescqipp.info/our-resources/bulletins/bulletin-295-inhaler-carbon-footprint

- 50.High quality low carbon asthma care. Greener Practice. Accessed October 2024. https://www.greenerpractice.co.uk/high-quality-and-low-carbon-asthma-care

- 51.Glossary of terms: carbon net zero and smart solutions. Crown Commercial Services. Accessed October 2024. https://assets.crowncommercial.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Glossary-of-terms_-Carbon-Net-Zero-and-Smart-Solutions-.pdf

- 52.Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. GINA. Accessed October 2024. https://ginasthma.org/reports

- 53.Guidance: Desflurane decommissioning and clinical use. NHS England. March 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/guidance-desflurane-decommissioning-and-clinical-use/

- 54.Nitrous oxide project. Association of Anaesthetics. Accessed October 2024. https://anaesthetists.org/Home/Resources-publications/Environment/Nitrous-oxide-project

- 55.Green surgery report: surgical care pathways. UK health alliance on climate change. Accessed October 2024. https://ukhealthalliance.org/sustainable-healthcare/green-surgery-report/surgical-care-pathways

- 56.Eii MN, Walpole S, Aldridge C. Sustainable practice: Prescribing oral over intravenous medications. BMJ. Published online November 6, 2023:e075297. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075297

- 57.Inhaler return and recycling. South East London ICS. 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.selondonics.org/our-residents/your-health/local-nhs-services/inhaler-return-and-recycling

- 58.Rizan C, Lillywhite R, Reed M, Bhutta MF. The carbon footprint of products used in five common surgical operations: identifying contributing products and processes. J R Soc Med. 2023;116(6):199-213. doi:10.1177/01410768231166135

- 59.Guides for Practices. SEE Sustainability. Accessed October 2024. https://seesustainability.co.uk/resources#c75ff997-ce4f-43d4-9626-a00b6afa477b

- 60.Green Impact for Health Toolkit. Royal College of GPs. Accessed October 2024. https://toolkit.sos-uk.org/greenimpact/giforhealth/login