Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

By the end of this article, you will be able to:

- Understand the rationale for adopting a person-centred approach when prescribing;

- Identify the prerequisite factors for the successful incorporation of patient-centred practice;

- Identify ways that person-centred prescribing can be incorporated into individual pharmacist prescribing and across teams.

RPS Competency Framework for All Prescribers

This article aims to support the development of knowledge and skills related to the following competencies:

- Domain 3: Present options and reach a shared decision (all statements);

- Domain 5: Provide information (all statements);

- Domain 8: Prescribe professionally (8.4 ‘Makes prescribing decisions based on the needs of patients and not the prescriber’s personal views’).

Introduction

The Royal College of General Practitioners defines person-centred care as “holistic, empowering” care that “tailors support according to the individual’s priorities and needs”[1]. Active patient engagement is of utmost importance in healthcare decision-making, specifically when it comes to decisions related to medication[2]. By prioritising the needs, preferences and values of the individual, person-centred practice ensures that prescribing decisions align with their overall wellbeing.

Research examining the integration of person-centred care into the practice of pharmacists has indicated positive outcomes, including enhanced medication adherence, improved health communication and stronger patient-provider relationships[3]. These studies have demonstrated that patients are actively engaged in consultations, especially in discussions about their treatment plans, and demonstrate increased motivation to self-manage their chronic illnesses[4].

Access the prescribing advice and support from the RPS here or click on the images below.

Whether you’re interested in becoming a prescriber, need advice on how to find a designated prescribing practitioner, or are currently working as a prescriber and looking to expand your scope of practice, the RPS has produced a range of resources to help you practice safely and confidently.

This article will explore the rationale behind adopting a person-centred approach to prescribing, consider the external environment and provide examples of how person-centred approaches can be incorporated into individual prescribing practice and across teams in the context of pharmacy.

It is recommended that you read this article in conjunction with these resources from The Pharmaceutical Journal:

- ‘How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting‘;

- ‘How to build and maintain trust with patients‘;

- ‘How to provide patients with the right information to make informed choices‘.

To help further expand your prescribing skills, additional related articles are linked throughout. You will also be able to test your knowledge by completing a short quiz at the end of the article.

Definitions

- Holism: an understanding that individuals are complex and health and wellbeing is influenced by various interconnected factors. It emphasises the need to consider the physical, psychological, social and cultural aspects of a person’s life when making prescribing decisions;

- Personhood: recognises that individuals are not just patients or recipients of healthcare services but unique, each with their own identities, experiences and aspirations. It emphasises treating each person with dignity, respect and empathy, valuing their autonomy and involving them in decisions about their care;

- Person-centredness: an approach that prioritises the needs, preferences and values of the individual when making healthcare decisions. It involves active listening, shared decision making and collaborative goal setting between the healthcare professional and the patient.

Principles of person-centred care

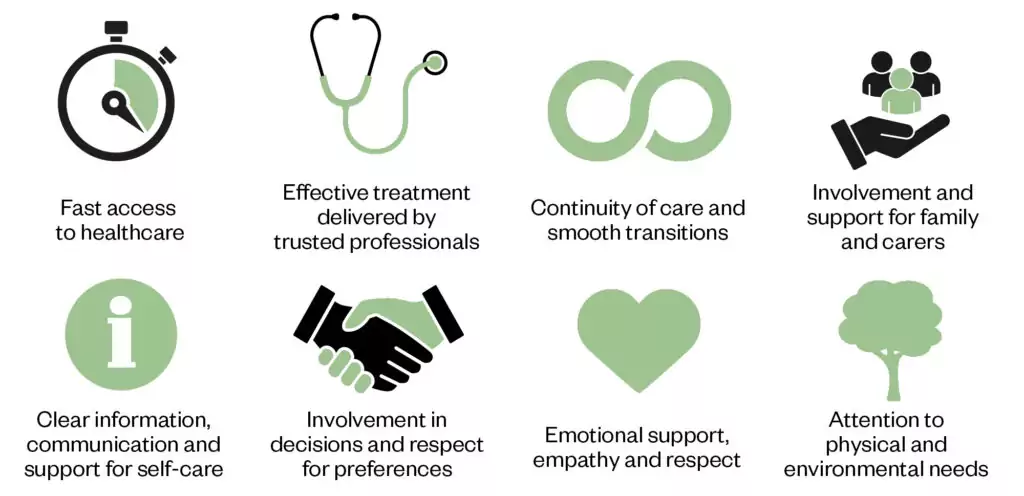

Unpacking the different components of personhood is complex. Different models and frameworks have been developed to help healthcare professionals understand the underlying principles of person-centred care and support its implementation into practice. The Picker Institute Europe, a non-profit organisation dedicated to developing a patient-centred approach to healthcare, has conducted extensive research — including focus groups with patients, family members, caregivers and clinicians — to develop eight principles of person-centred care (see Figure)[5]. These principles focus on factors that matter most to all those who use care services and define the important elements that should remain non-negotiable in the delivery of care[6]. Organisations are encouraged to implement these principles to advocate for the continued placement of people at the centre of care provision. There is an increasing need to move away from paternalistic approaches where patients are told what treatment they will be receiving, towards collaborative relationships where the knowledge, values, preferences and specific circumstances of everyone is taken into account when jointly deciding how to manage their care.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

The Health Foundation has also developed a framework that identifies four principles of person-centred care[7]:

1. Affording people dignity, compassion and respect;

2. Offering co-ordinated care, support or treatment;

3. Offering personalised care, support or treatment;

4. Supporting people to recognise and develop their own strengths and abilities to enable them to live an independent and fulfilling life.

Focus in practice — using person-centred approaches to support adherence

Individuals with chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension and asthma, often struggle with medication adherence. Non-adherence can have various underlying causes, the most common reason cited by patients is ‘pill burden’. This is where the role of pharmacists as prescribers becomes exceptionally valuable, as they are uniquely placed to provide tailored support to patients by placing their needs at the forefront during consultations, particularly when managing their polypharmacy. A pharmacist adopting a person-centred approach can isolate the specific factors contributing to their pill burden, leading to mutually agreed solutions that will improve adherence[8].

Person-centred approaches in practice

Person-centred prescribing is influenced by the external environment in which it is practiced. Consider how different the experience will be for patients receiving treatment in a busy hospital ward compared with a one-to-one consultation carried out at their home. The external environment may not be something prescribers can change but, by considering its potential impact on the person, it may be possible to identify opportunities to make small but effective accommodations (e.g. moving a conversation to a quieter or more private setting).

Person-centred care requires multidisciplinary approaches recognising the individual’s capacity to manage and improve their own health[9]. Effective implementation of person-centred practice also places different demands on prescribers, staff and the health system; it requires excellent communication skills and the capacity to respond flexibly to individual needs. Active listening, empathy and the ability to provide clear explanations of treatment options are crucial when facilitating shared decision making.

The method of communication should be tailored to the patient demographic and the setting in which you are working. For example, the communication style adopted during a remote consultation will be different from when a patient is seen in a face-to-face clinic setting. Similarly, where the patient may present with impaired capacity, how you communicate with them or their carer will differ to someone who is fully cognisant. This topic can be explored in greater depth by reading ‘Pharmacy consultations with patients with learning disabilities’.

For person-centred practice to be successful, it should be embraced at all levels of the healthcare system, as well as by policymakers, educators and the public. A good example of wide-scale adoption of person-centred practice is the ‘Hello My Name is’ campaign. This grassroots initiative serves as a reminder to healthcare professionals of the importance of simple gestures and that a proper introduction is an important first step in establishing meaningful trusted relationships with patients.

The prescriber will be unable to provide effective person-centred care without a strong knowledge base and clinical competence. Prescribers need to provide patients with accurate and up-to-date information to enable an informed discussion of treatment options.

The four principles outlined below briefly describe ways that person-centred practice can be incorporated into prescribing:

1. Understand the person

Recognising the differences among individuals is essential for fostering a productive and personalised shared decision-making process. For example, a patient’s cultural beliefs and values, language proficiency, socioeconomic status and personal views can significantly influence their health-related choices and attitudes towards medications[10,11]. Healthcare professionals should avoid making assumptions and approach each patient with an open mind, ensuring that care is tailored to individual needs and preferences. By taking the time to comprehend these diverse aspects, healthcare professionals can tailor their approach and engage in meaningful conversations about care. For example, a Muslim patient will need specific support managing their medication when fasting during Ramadan. Similarly, for Hindu patients, considerations will need to be made for their dietary requirements when prescribing treatments that may contain animal products.

By understanding and respecting these differences, healthcare providers can collaboratively design a care plan that aligns with the patient’s values, resulting in improved adherence and better outcomes. Embracing patient diversity and actively engaging with patients on an individual level fosters a patient-centred care model that prioritises both the physical and emotional well-being of the patient. The case-based learning article ‘Insulin intensification in a Hindu patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus‘ explores how this can be applied to a practice example.

2. Assess the impact of socio-economic factors

The impact of social determinants on an individual’s health outweighs the influence of the quality and quantity of healthcare they receive[12]. Factors such as employment status, overall wellbeing, living conditions and income play a significant role in shaping health outcomes. These non-medical factors have a profound effect on a person’s overall health and should be given due consideration in the context of person-centred prescribing. This includes assessing factors, such as affordability of medication, access to healthcare resources and social support systems. Prescribers may need to explore medication assistance programs or provide information on more affordable alternatives to ensure patients can access and adhere to their prescribed medications. Non-pharmacological interventions with support from social prescribers may be required to provide a holistic approach to patient care that is much more tailored to their needs and targets underlying factors contributing to their ill health.

A full discussion of the social determinants of health is beyond the scope of this article but further reading has been identified at the end of the article.

3. Facilitate shared-decision making

Treatment options should be clearly explained to patients, including the benefits and risks associated with each choice. By considering the patient’s preferences, values and beliefs, shared decision-making can lead to treatment plans that align with the patient’s goals and enhance their adherence to medication regimens.

The ‘Year of Care’ initiative serves as an excellent illustration of efforts to implement shared decision-making for individuals with long-term conditions[13]. It emphasises the use of personalised care and support planning to ensure that interactions between patients with long-term conditions and healthcare professionals are meaningful and impactful with healthcare that focuses less on ‘fixing’ a patient’s illness and more on supporting them to manage their condition independently.

4. Collaborate with the multidisciplinary team

Person-centred prescribing relies on the full involvement of the multidisciplinary team. Involving physicians, nurses and other allied healthcare professionals can enhance the quality of care provided to patients and ensure that the individual preferences and circumstances of the patient are understood by the full team.

An evidence-based approach developed by academics at King’s College London, known as ‘Experience-Based Co-Design’ (EBCD), offers a method for enhancing people’s healthcare experiences[14]. It involves gathering feedback and experiences from both patients and staff and using this information to collaboratively develop service improvements. By adopting the EBCD approach, healthcare professionals are encouraged to reframe their perspectives and view healthcare from the patients’ standpoint. This enables them to work alongside patients in identifying and implementing often small yet impactful changes that significantly enhance the overall patient experience of care.

The following case study explores how a prescribing pharmacist can adopt a person-centred approach during a routine consultation:

Case in practice

Patient profile: Mrs Smith, aged 65 years, is visiting a pharmacist prescriber in their hypertension clinic at a GP practice. She had been asked to monitor and record her blood pressure over the previous two weeks. Mrs Smith currently takes no medication and enjoys going out with her friends and family. She loves playing with her two-year old grandchild and plays tennis every week.

Background: The prescribing pharmacist has discussed Mrs Smith’s recent blood pressure results. The results Mrs Smith has brought in today indicate she has consistently raised blood pressure and could benefit from the prescription of a new antihypertensive medication.

When discussing the blood pressure results, the pharmacist has informed the patient about the risks of leaving high blood pressure untreated and explained the medical options available that can help manage the risk of stroke and heart attack. Mrs Smith agrees to start on a new antihypertensive medication but is concerned about the potential side effects and the impact on her daily life, as she values her independence and enjoys an active lifestyle.

Reflective questions: How can incorporating person-centred care principles support Mrs Smith as she considers the use of antihypertensive medication?

What strategies would you employ to establish rapport and create a comfortable environment for open communication with the patient?

Reflecting on the shared decision-making process, what challenges are you likely to encounter during the discussion and how would you address them to ensure the patient’s involvement and satisfaction with the treatment decision?

What additional patient-centred approaches can be incorporated into the care plan for the patient?

Answer guidance is available at the end of the article.

Questions for reflection

- How has incorporating patient-centred care impacted your prescribing practice? Reflect on specific instances where you have prioritised patient perspectives and needs during consultations.

- What challenges and barriers have you encountered when implementing patient-centred care? How have you addressed these challenges, and what lessons have you learned from them?

- How have you effectively engaged patients in shared decision-making during the prescribing process? Reflect on strategies you have employed to ensure patients are actively involved in treatment decisions and how this has influenced patient outcomes.

- Reflect on a recent patient case where you successfully incorporated patient-centred care principles into your prescribing practice. What were the key factors that contributed to a positive patient experience, and how can you apply those learnings to future cases?

Knowledge check

Expanding your scope of practice

The following resources expand on the information contained in this article.

Organisations and resources to promote person-centred practice:

- The Point of Care Foundation

- ‘Top tips: person-centred care‘, Royal College of Physicians

Background information on experience-based co-design:

- ‘Working together to improve healthcare services‘, King’s College London

- ‘The experience-based co-design approach – how the method works‘, King’s College London

- See the presentation ‘Goal Attainment Scales (GAS) in person-centred pharmacy consultations‘ for information on how coaching approaches can be used when setting goals with patients

Health inequalities

- ‘Social and economic consequences of health status‘, The Health Foundation

Model answers for case study

Pharmacist actions:

- Establishing rapport: the pharmacist starts by introducing themselves and creating a comfortable environment for open communication. They establish rapport with Mrs Smith, ensuring she feels heard and respected;

- Assessing the patient’s needs: the pharmacist takes a holistic approach and begins by understanding Mrs Smith’s lifestyle, preferences and concerns related to her hypertension treatment. They explore her daily routines, physical activities and any potential barriers to medication adherence;

- Providing information: the pharmacist educates Mrs Smith about hypertension, its long-term consequences and the importance of medication adherence. They use clear and simple language, avoiding medical jargon and ask Mrs Smith to repeat back or summarise the information provided to check she fully comprehends the information;

- Addressing concerns: The pharmacist actively listens to Mrs Smith’s concerns about potential side effects. They explain the common side effects associated with the prescribed medication, such as dizziness or fatigue, and reassure her that most side effects are temporary and often diminish with time;

- Shared decision-making: the pharmacist involves Mrs Smith in shared decision-making, presenting alternative antihypertensive options and discussing their benefits and potential side effects. They consider Mrs Smith’s preferences and work collaboratively to select a medication that aligns with her lifestyle and minimises any potential impact on her daily activities;

- Individualised care plan: based on the shared decision, the pharmacist develops an individualised care plan for Mrs Smith, including medication dosing instructions, potential side effects to monitor and lifestyle modifications to complement her treatment;

- Monitoring and follow-up: the pharmacist schedules a follow-up consultation to monitor Mrs Smith’s response to the medication, address any further concerns and provide ongoing support for medication adherence and lifestyle modifications.

Outcome:

Through patient-centred pharmaceutical care, the pharmacist successfully addresses Mrs Smith’s concerns, actively involves her in decision-making and tailors the treatment plan to her needs and preferences. Mrs Smith feels empowered and confident in managing her hypertension, leading to improved medication adherence, better health outcomes and enhanced overall patient satisfaction.

- 1Person-Centred Care toolkit. Royal College of GPs. https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/mod/book/view.php?id=12953 (accessed Sep 2023).

- 2Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared Decision Making — The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–1. doi:10.1056/nejmp1109283

- 3Fitzpatrick K, Addie K, Shaw M, et al. Implementing an innovative, patient-centered approach to day case arthroplasty: improving patient outcomes through remote preoperative pharmacist consultations. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2023;:ejhpharm-2022-003573. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2022-003573

- 4Basger BJ, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Uptake of pharmacist recommendations by patients after discharge: Implementation study of a patient-centered medicines review service. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23. doi:10.1186/s12877-023-03921-2

- 5Patient centred professionalism – defining the public’s expectations of doctors . Picker Institute. 2008.https://picker.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Patient-centred-professionalism-…-1.pdf (accessed Sep 2023).

- 6Impact Report 2020-2021. Picker Institute. https://picker.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Picker-Impact-Report-2021-WEB-updated.pdf (accessed Sep 2023).

- 7Person-centred care made simple. The Health Foundation. 2014.https://www.health.org.uk/publications/person-centred-care-made-simple#:~:text=Person%2Dcentred%20care%20supports%20people,the%20needs%20of%20the%20individual (accessed Sep 2023).

- 8Koshy S. The Practice of Polypharmacy: Do Pharmacists Have A Role? J Pharma Care Health Sys. 2016;03. doi:10.4172/2376-0419.1000153

- 9Coulter A, Oldham J. Person-centred care: what is it and how do we get there? Future Hosp J. 2016;3:114–6. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.3-2-114

- 10Burggraf L, Stark S, Schedlbauer A, et al. 10 Ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE) in general practice consultations – report of a mixed methods study. Oral Presentations. 2019. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2019-pod.24

- 11Shahin W, Kennedy GA, Stupans I. <p>The impact of personal and cultural beliefs on medication adherence of patients with chronic illnesses: a systematic review</p> PPA. 2019;Volume 13:1019–35. doi:10.2147/ppa.s212046

- 12Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed Sep 2023).

- 13NHS Year of Care. NHS Year of Care Partnerships. https://www.yearofcare.co.uk/ (accessed Sep 2023).

- 14Experience-based co-design toolkit. The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/ebcd (accessed Sep 2023).

2 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Very useful information on patient centred approach in practice.

How do I get answers to the quiz?

Many thanks for your comment. I am senior editor for research and learning at The Pharmaceutical Journal. We have looked at this and there was a problem with the quiz functionality preventing the score and answers from displaying. This has now been fixed so please do try it again and let me know if you continue to have problems. My email address is alex.clabburn@rpharms.com.