Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are common and account for around 5% of all[1]

, and up to 16.6% in the elderly[2]

hospital admissions. Approximately 10%–20% of inpatients suffer at least one ADR during their hospital stay. ADRs often adversely affect the individual’s quality of life; may reduce medication adherence; often increase (direct or indirect) costs of care; and may result in death in about 0.1%–0.3% of hospitalised patients[3]

.

An ADR is an unintended, undesirable effect of a properly prescribed dose of a medication. It differs from an adverse drug event (ADE) that occurs during treatment with an agent, but is not necessarily caused by the pharmacology of the agent or have a casual relationship with it, and may result from medication errors. Six different subtypes[4]

of ADRs are A: Augmented, B: Bizarre, C: Chronic, D: Delayed, E: End of use or withdrawal, and F: Failure (unexpected) of therapy. Type A (augmented) ADRs are the most common and account for 80% of total ADRs that may occur in the hospital setting or result in hospitalisation[3]

; are because of the augmentation of known pharmacologic effect(s) of the drug; and are often dose-dependent and predictable. Antibiotics, anti-neoplastic agents, cardiovascular drugs — especially diuretics and the inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), anti-diabetic agents, anti-inflammatory agents, anticoagulants, and opiates are the common drug classes responsible for ADRs in adults[1]

.

ADRs are common at extremes of ages. Developmental changes affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of many drugs in the pediatric population. Similarly, the elderly are at increased risk of ADRs because of their increased pharmacodynamic sensitivity, decreased renal or hepatic clearance, reduced cytochrome P450 (CYP) oxidation[5]

, and changes in the volume of distribution because of the decrease in lean body mass and total body water. The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease increases with age, often resulting in polypharmacy, and thereby increasing the risk of ADRs.

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a well accepted and effective approach for the management of patients at high cardiovascular risk, including patients with hypertension, diabetes, heart failure and chronic kidney disease. However, due to the important vascular and renal properties of the angiotensin II (Ang II), its blockade in some circumstances is associated with occurrence of untoward side effects like hypotension or acute kidney injury (AKI), and has been reported in over 40% of the individuals over 65 years of age[6]

,[7]

. In addition, acute infectious illnesses — such as influenza, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, and diarrhoeal illnesses — increase the risk of dehydration and volume depletion. This exacerbates the risk of AKI and other ADRs, as the parent drug or its metabolites accumulate because of reduced renal clearance. To reduce ADRs, it is important that the medications that precipitate AKI and the others that could accumulate because of reduced renal clearance should be withheld during the periods of acute illness. The Canadian Diabetes Association[8]

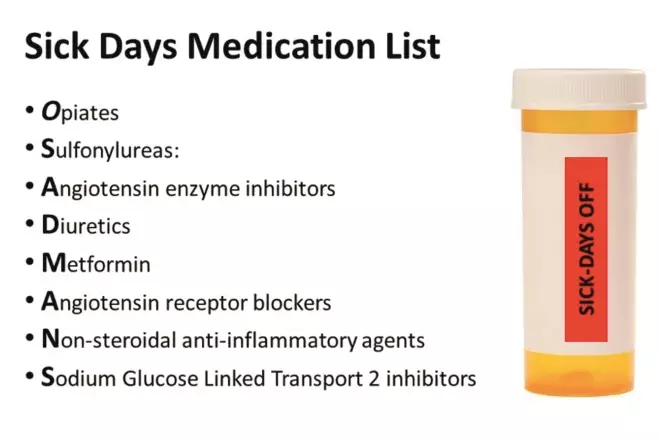

has developed a simple, easily memorable SADMANS pneumonic for the “Sick Day Medication List”, highlighting the need to hold medications that are likely to cause ADRs during such periods.

Many healthcare providers, especially nephrologists, advise patients to hold these medications of the SADMANS group during such periods, and some even give printed sheets to patients as a reminder. However, patients or their family members often do not remember to hold these medications during such times and continue to take these medications and often present to emergency department with the consequences resulting from dehydration, AKI, hypoglycemia, or hyperkalemia. Often, they require hospitalisation; at times may require invasive therapy like dialysis; and may prolong their length of stay. In addition, various opiates or their metabolites accumulate in renal failure and may cause altered mental state often resulting in expensive imaging investigations in such circumstances and increase costs of care. I propose to expand the SADMANS list to include opiates in this category as well and call it “O SADMANS” list (Figure 1).

Figure 1: O SADMANS list

Source: Malvinder S Parmar

List of medications to be held during periods of acute dehydrating illnesses, and proposed warning label on medication containers

Despite patient education and the knowledge among healthcare providers, the risk of such ADRs during periods of acute illnesses remains significant, though easily preventable[6]

,[7]

. All healthcare providers, including allied health, have an important role in preventing ADRs, but pharmacists play a vital role in the pharmacovigilance process. I propose that a red-colored warning label, with “SICK-DAYS OFF” should be affixed on each of these medication containers (Figure 1). This simple procedure is feasible, inexpensive, and would likely be extremely effective in reminding patients or their care-givers to hold these specific medications during these periods of acute illness. I hope that this would make these at-risk patients recall the discussion between them and their healthcare providers so that they do not take these medications during the periods of acute illness, or to review their concerns, if any, with their providers. However, implementation of the initiative requires acceptance by the medical community and support of the pharmacists, especially at the community pharmacies. I invite pharmacists and sincerely hope that they, especially at the community pharmacies, take this simple initiative to reduce some of the ADRs related to these commonly used medications.

Malvinder S Parmar, MB, MS, FRCPC, FACP, FASN

Professor of Medicine, Northern Ontario School of Medicine

Consultant Physician, Internal Medicine & Nephrology

Timmins and District Hospital, Ontario, Canada

References

[1] Kongkaew C, Noyce PR & Ashcroft DM. Hospital admissions associated with adverse drug reactions: a systematic review of prospective observational studies. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42(7):1017–1025

[2] Petrovic M, van der Cammen T & Onder G. Adverse drug reactions in older people: detection and prevention. Drugs Aging 2012;29(6):453–462

[3] Pirmohamed M, Breckenridge AM, Kitteringham NR et al. Adverse drug reactions. BMJ 1998;316(7140):1295–1298

[4] Edwards IR & Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 2000;356(9237):1255–1259

[5] Brahma DK, Wahlang JB, Marak MD et al. Adverse drug reactions in the elderly. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2013;4(2):91–94

[6] Elgendy IY, Huo T, Chik V et al. Efficacy and safety of angiotensin receptor blockers in older patients: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Hypertens 2015;28(5):576–585

[7] Chaumont M, Pourcelet A, van Nuffelen M et al. Acute kidney injury in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease: do angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors carry a risk? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016;18(6):514–21

[8] Cheng AY. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Introduction. Can J Diabetes 2013;37 Suppl 1:S1–3