Abstract

Aim

To identify and describe (i) pharmaceutical needs assessment (PNA) activity and (ii) the awarding of new NHS community pharmacy contracts in primary care trusts in England.

Design

A self-completion questionnaire.

Subjects and setting

All PCTs in England.

Results

The response rate was 74%. 90% of PCTs had completed a PNA of which 85% had used one or more resources to assist with the process of undertaking a PNA. Local community pharmacists were engaged in the process in most (92%) PCTs. Other stakeholders can be grouped into those with high, moderate and low levels of engagement. 90% of PCTs had analysed the findings of their PNA, and those who had undertaken them earlier were significantly more likely to have used the results when commissioning services (P=0.026). 116 PCTs (54%) had approved a total of 194 new community pharmacy contracts since 1 April 2005, two thirds of which were exempt from control-of-entry regulations and were concentrated in a minority of PCTs.

Conclusions

PNAs have been undertaken by most PCTs, with high levels of activity in the months leading up to implementation of the new contract. Local PNAs are important to PCTs when planning and commissioning pharmaceutical services provision.

Understanding the needs of local populations is fundamental to the planning and provision of health services. In the 19th century the first medical officers for health were responsible for assessing the needs of their local populations.1 Since then, approaches and methods for understanding health needs have been developed and refined, and work of this kind is now referred to as health needs assessment.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) defines health needs assessment as “a systematic method for reviewing the health issues facing a population, leading to agreed priorities and resource allocation that will improve health and reduce inequalities”.2 Health policy highlights the importance of health needs assessment to primary care trusts, to enable understanding of local needs in order to commission the most appropriate services.3

Thus, a pharmaceutical needs assessment (PNA) focuses on pharmaceutical needs. PNAs are now an important process for those planning pharmaceutical services provision, in particular PCTs commissioning services through the new contractual framework for community pharmacy. “Choosing health through pharmacy” highlights the task of assessing the health and social needs of the local community as one of the 10 key roles for pharmacy in public health.4 National Pharmacy Association guidance identifies planning as a key stage of the commissioning cycle.5 Planning involves assessing needs and resources, before going on to develop contracts with providers to meet identified needs.

Resources are available to support PCTs in the process of carrying out PNAs, for example the National Primary and Care Trust Development Programme (NatPaCT) developed a PNA “toolkit” which emphasises the importance of ensuring input from key stakeholders, including local community pharmacists, as well as other health care professionals.6 Although many studies on needs assessments in hospital and general practice care have been published, this is not the case for community pharmacy. Williams et al used the term “PNA” in their 2000 study identifying the roles that a pharmacist could deliver from a general practice base,7 and Porteous and Bond described a PNA undertaken to assess needs in a geographical area.8 Aside from these small-scale studies, there is little published evidence available on needs assessments relating to community pharmacy.

PNAs are also directly relevant to the reformed rules for control of entry, the process through which a PCT decides whether an application to establish a new pharmacy is desirable or necessary.9 The Pharmaceutical Regulations 2005 (Regulation 13)10 introduced reforms to the control-of-entry system for community pharmacy by establishing four exemptions. For three of these exemptions (those pharmacies based in large, out-of-town shopping centres, opening for at least 100 hours per week or that are part of one-stop primary care centres), pharmacies must provide a “directed” list of services specified by the PCT. NatPaCT guidance emphasised the importance of completing PNAs before April 2005 as a factual basis for determining which services are included on these lists.9

The aim of this paper, therefore, is to present findings from a national commissioning survey of PCTs to quantify the extent of PNA activity in PCTs in England and identify the resources used, the stakeholders involved in the process, and the ways in which the findings have been used.

Methods

A questionnaire about the commissioning of pharmaceutical services was distributed to all PCTs in England during March 2006. Two mailings took place, the first to all PCT chief executives with the intention that they would forward the questionnaire to the “community pharmacy commissioning lead”, ie, the person at the PCT with primary responsibility for commissioning services from community pharmacy.

A reminder mailing was sent direct to commissioning leads. Non-responders were reminded twice either by e-mail or telephone. Paper copies and an online version of the questionnaire were made available.

The questionnaire was designed by the research team with input from “experts” with PCT and community pharmacy backgrounds. The questionnaire was piloted with five PCT pharmaceutical advisers and, subsequently, minor revisions were made.

The questionnaire covered the following topics:

- Implementation of the new pharmacy contract

- Commissioning of enhanced services

- PCT approaches to commissioning phar-maceutical services

- Access to medicines

- Management of long-term conditions

- Public health

This paper presents findings relating to PNA activity and the award of new pharmacy contracts. Respondents were asked for details on PNAs undertaken before and after implementation of the new community pharmacy contract, and to specify which resources they had used and which stakeholders had been involved in the process. Due to the relevance of PNAs to the reformed control-of-entry rules, results on the numbers of new pharmacy contracts approved since the new contract was introduced and the proportion of these that were exempt from control of entry regulations were also included.

Data analysis

Data were entered into SPSS v13.0 for analysis. The analysis involved the use of simple descriptive statistics, including frequency counts and cross-tabulations of variables. A chi-squared test was used to test for association between variables. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

At the time of distribution, the official number of PCTs in England was 303. However, a number of respondents indicated that some PCT reconfiguration had begun and some PCTs already had integrated management structures. This resulted in a revised sample size of 290, and questionnaires were received covering 216 PCTs, representing a corrected response rate of 74 per cent. Non-respondent PCTs were randomly distributed across England, with no evidence of geographical clustering.

Demographics of the respondents

One hundred and ninety-eight respondents (92 per cent) worked within a pharmacy or medicines management team. The length of time that respondents had spent in their current role ranged from one month to almost 16 years, with the mean being three years and eight months. One hundred and forty-eight (70 per cent) were female, and 68 (30 per cent) male. Ninety-five respondents (45 per cent) were in the 35–44 years age group, making this the most common age category, followed by 65 people aged 45–54 years (31 per cent), 33 aged 25–34 (16 per cent) and 17 aged 55–64 (8 per cent).

PNA activity across England

By March 2006, 214 PCTs (99 per cent) had at least begun the process of undertaking a PNA, with 194 (90 per cent) having completed at least one. A further 20 (9 per cent) had a PNA “in progress” and two (1 per cent) had not yet started the process.

Of the 194 PCTs that had completed at least one PNA, 122 (62 per cent) had completed a PNA before the new community pharmacy contract was implemented (1 April 2005). Of these, 105 (86 per cent) were completed between January and March 2005. Across the whole sample, seven PCTs (3 per cent) had undertaken two PNAs, with the interval between them ranging from six to 24 months.

Resources used when undertaking PNAs

The questionnaire contained a list of resources available to assist with the process of conducting PNAs and respondents were asked to state which they had used. Of the 214 PCTs that had started a PNA, 182 (85 per cent) had used one or more resources. The NatPaCT toolkit was the most frequently cited resource; this was used by 168 PCTs (79 per cent). Twenty-eight PCTs (13 per cent) had commissioned a commercial consultancy to undertake either the entire PNA or a smaller piece of work, such as a patient survey, which fed into the overall assessment.

Respondents were also asked to state any additional resources that had been used and 25 PCTs (12 per cent) did so. Two types of resource were identified. First, sources of guidance on the actual process such as resources from a local university or the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) were used. Second, use was made of various health and sociodemographic data, including the national census, prescribing data and local patient surveys.

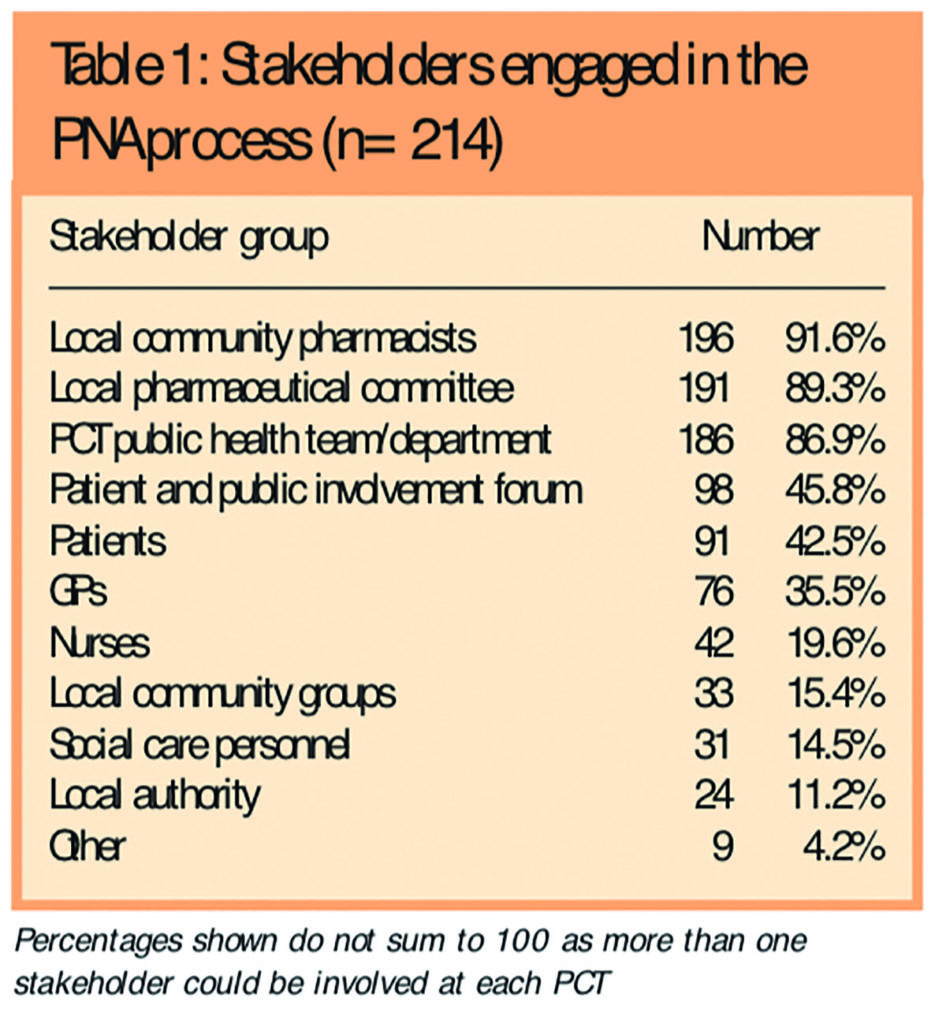

Stakeholders involved in the PNA process

The questionnaire contained a list of potential stakeholders in the PNA process and, as with the question on resources, respondents were asked to state which had been involved and to specify any others. The results, presented in Table 1, can be categorised into high, moderate and low levels of engagement.

The highest levels of engagement were found for local community pharmacists, local pharmaceutical committees and PCT public health teams. Patient and public involvement forums, individual patients and GPs were moderate level stakeholders, and nurses, local community groups, social care personnel and local authorities were all low level.

Other stakeholders, involved at a small number of PCTs, included non-executive PCT directors, local medical committees and drug misuse agencies.

Use of PNAs by PCTs

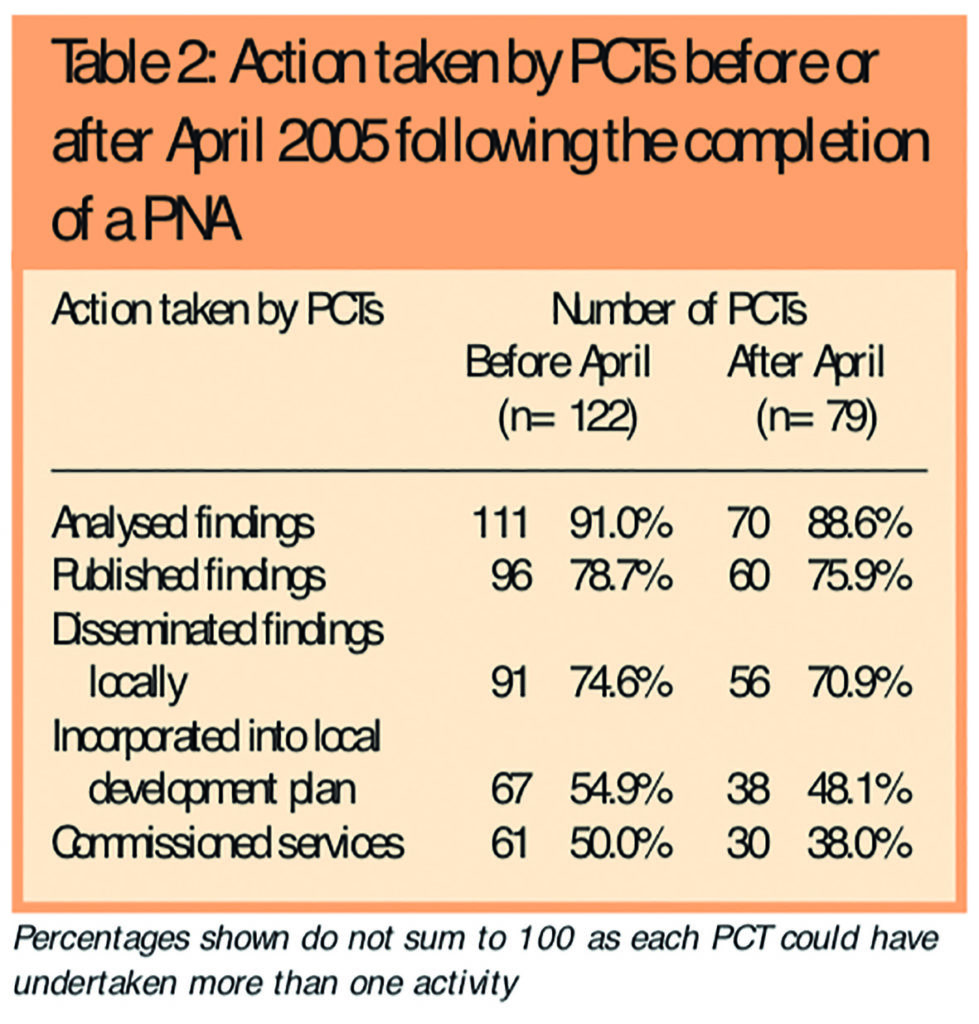

Table 2 shows the use made of findings derived from PNAs by PCTs.

Of the PCTs that had completed one or more PNAs, 175 (90 per cent) had analysed the results, and many had published these and disseminated the findings locally. Results for actively incorporating the findings into local decision making were lower; 87 PCTs (45 per cent) had used results to inform the commissioning of services, while 100 (52 per cent) had incorporated findings into their local development plan (LDP).

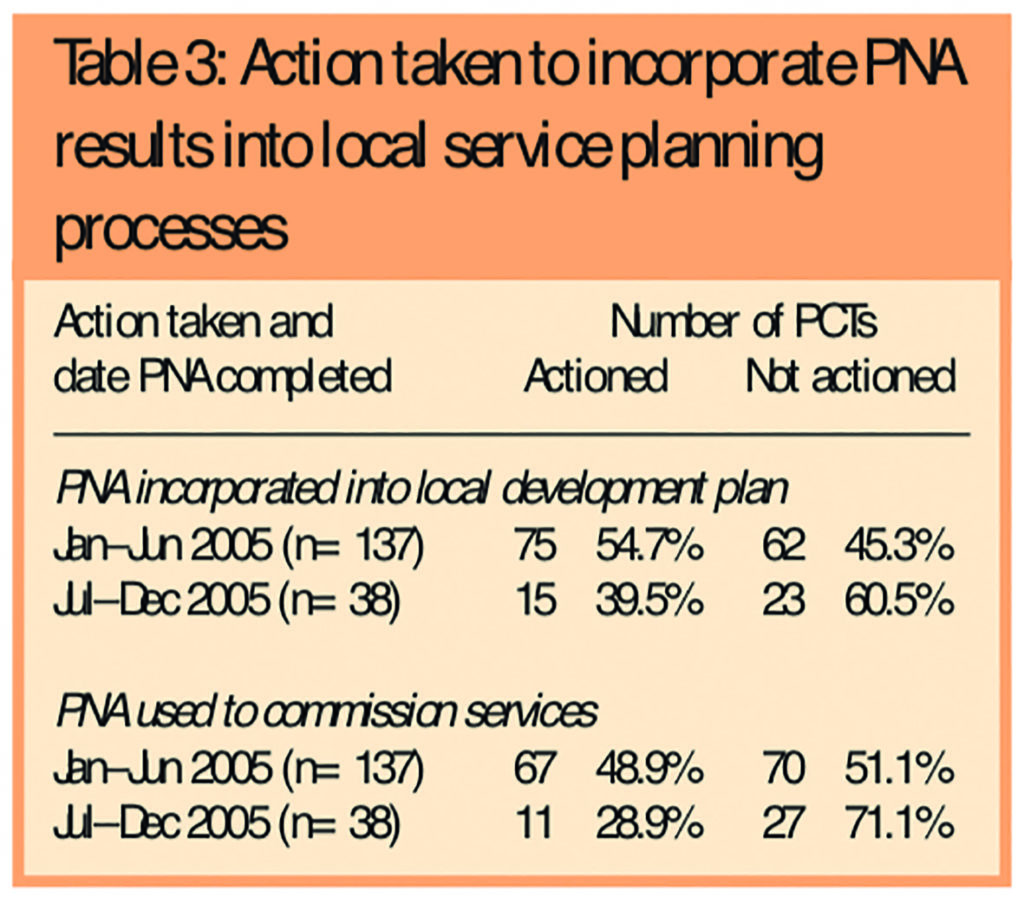

Of the 194 PCTs which had completed at least one PNA, 175 had done so during 2005. Table 3 presents results on the numbers of these PCTs which had used PNA results directly in their local planning process, and divides PCTs according to whether they had undertaken the PNA in the first (January to June) or second (July to December) half of 2005. PCTs that had undertaken a PNA earlier were significantly more likely to have used PNA results when commissioning services (P=0.026).

No significant difference was found between the time when the PNA had been completed and whether the results had been incorporated into the LDP (P=0.088).

New pharmacy contracts

A total of 194 new pharmacy contracts had been approved, distributed across 116 PCTs, since 1 April 2005. Of these, 135 (70 per cent) met criteria exempting them from the control-of-entry regulations. Across all 216 responding PCTs, 65 (30 per cent) had at least one pharmacy open for 100 hours or more per week. One hundred PCTs (46 per cent) had approved no new contracts and 151 (70 per cent) had no pharmacies that were open for 100 hours or more per week.

The results showed that the approval of new pharmacy contracts is concentrated in particular, often metropolitan, areas: two-thirds of the new contracts (126) had been approved in a quarter of PCTs (52 PCTs, 24 per cent). Thirty-four (25 per cent) of the new contracts that had been approved and were exempt from the control-of-entry regulations were situated within just 11 PCTs (5 per cent of the respondent sample).

A final point on access to NHS pharmaceutical services is that provided out-of-hours. From data collected elsewhere in the survey, we found that while most PCTs (146, 68 per cent) believed that the provision of NHS pharmaceutical services is largely covered during the daytime (9am–5pm) at weekends. This dropped to 66 (30 per cent) for weekday evenings (6pm–10pm) and not surprisingly to just 14 (6 per cent) for cover across 24 hours, seven days a week.

Only in 65 PCTs (30 per cent) are one or more pharmacies contracted to provide services for a minimum of 100 hours per week.

Discussion

The questionnaire had a high response rate and provides useful data on PCT PNA activity which have not been previously collected. The findings show that PNAs have been undertaken in nearly all respondent PCTs. A range of resources have been used and a variety of stakeholders involved in the process. Most PCTs have analysed and published the findings of their PNAs, but fewer have made direct use of them in the commissioning process.

Work to map and address the pharmaceutical needs of populations has been a key activity for those involved in planning and developing community pharmacy services even before the implementation of the new community pharmacy contract, although not always as part of a formal process, or necessarily termed as a PNA. PNAs are important for patients, PCTs and community pharmacists in addressing inequalities, ensuring better use of resources and helping to develop professional skills.

The findings do not provide any information about the quality or coverage of the PNAs undertaken, or their rigorousness. Similarly, while data are presented on the range of stakeholders involved it is not possible to assess the level of engagement these stakeholders had in the process, or the number, for example, of patients consulted in each area. The data collected represent experiences of commissioning services from a PCT perspective, and do not provide any insight into pharmacy contractors’ views.

Our ongoing evaluation work at case study sites will explore these issues in greater depth.

These findings reflect the experiences of PCTs that undertook needs assessments as part of the local pharmaceutical service (LPS) pilot site planning process. The LPS evaluation also found that PCTs involved a range of stakeholders.12 Several LPS sites had the support of a commercial agency made available to them and this was seen as a particularly useful resource, with some PCTs stating that they would have struggled to find the capacity to undertake such detailed work without the agency. However there are now several additional sources of support and resources available, and this survey shows that many PCTs are making use of these, and the use of commercial agencies is low.

The high level of activity in the months before April 2005 suggest a push in many PCTs to complete the process in the run-up to the introduction of the new contract. Further research should determine whether levels remain this high now that the contract has been implemented.

Translating the results of PNAs into action is an important challenge for PCTs. The fact that those that undertook PNAs earlier have made more use of their results in the local planning process is not surprising, since they have had more time to do so. It may be the case that more of the PCTs that have undertaken PNAs more recently will go on to feed the results into their planning process in this way.

Recently published data show a marked increase in the number of new pharmacies that opened in the 12 months to March 2006 compared with previous years. During this period 143 new pharmacies opened, which is the largest number of openings for 10 years.13 Our survey showed that most of new contracts approved (70 per cent) were exempt from the control-of-entry regulations.

The increase in the number of new contracts approved can be taken as a sign of renewed interest and confidence in community pharmacy. It is not surprising that two-thirds of these meet the criteria for exemption from control-of-entry regulations.

Further work is needed, however, to inform the current review14 and discover the impact these “exempted” pharmacies are having on consumer convenience and access to medicines and other NHS services, and whether they are augmenting or simply replacing services provided by other community pharmacies serving the same population.

In terms of the distance to the nearest pharmacy of new pharmacy openings, recent data show that the greatest proportion of new pharmacy openings was within 500m of the nearest pharmacy, a reversal of the trend of the past 10 years, when pharmacies opening within 500m were always the lowest proportion.13 This is particularly important in the small number of PCTs where, as our survey shows, multiple “exempted” contracts have been approved.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues in PCTs who put significant effort into providing us with a huge amount of detailed data during a period of considerable turbulence.

This study was funded by the Department of Health.

This paper was accepted for publication on 24 July 2006.

About the authors

Fay Bradley, MA (Econ), and Rebecca Elvey, MA (Econ), are research associates, Darren Ashcroft, PhD, MRPharmS, is director of the Centre for Innovation in Practice and Peter Noyce, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Manchester.

Correspondence to: Rebecca Elvey, Centre for Innovation in Practice, The Workforce Academy, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL (e-mail rebecca.elvey@ manchester.ac.uk).

References

- Wright J, Williams R, Wilkinson JR. Development and importance of health needs assessment. BMJ 1998;316:1310–3.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Health needs assessment: a practical guide. London: NICE; 2005

- Department of Health. Shifting the balance of power within the NHS: securing delivery. London: The Department; 2001.

- Department of Health. Choosing health through pharmacy — a programme for pharmaceutical public health 2005–2015. London: The Department; 2005.

- National Pharmacy Association. Commissioning resource pack. St Albans: NPA; 2005.

- Celino G, Blenkinsopp A, Dhalla M. Pharmaceutical needs assessment toolkit. London: National Primary and Care Trust Development Programme; 2003.

- Williams SE, Bond CM, Menzies C. A pharmaceutical needs assessment in a primary care setting. British Journal of General Practice 2000;50:95–99.

- Porteous T, Bond C, Novel provision of pharmacy services to a deprived area: a pharmaceutical needs assessment, International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2003;11:47–54.

- PEC paper 8 — community pharmacy new contractual framework. London: National Primary and Care Trust Development Programme; 2005.

- The National Health Service (Pharmaceutical Regulations 2005) Statutory Instrument 2005 No. 641.

- NHS in England. Available at: www.nhs.uk/England/ AuthoritiesTrusts/Pct/list.aspx (accessed 28 July 2006).

- Elvey R, Kendall J, Bradley F, Ashcroft D, Hassell K, Sibbald B, et al. Processes and consequences in local pharmaceutical needs assessment: experiences of local pharmaceutical services pilots. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2005;13(Suppl):R11.

- Information Centre. General pharmaceutical services in England 2005–06 — emerging findings. Available at: www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/pharmservs (accessed 28 July 2006).

- Department of Health. Review of progress on reforms in England to the “control of entry” system for NHS pharmaceutical contractors. Consultation document. London: The Department; 2006.