Shutterstock.com / yellow card.mhra.gov.uk

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Identify adverse events and know how they are categorised;

- Understand how suspected and confirmed adverse events should be managed;

- Know what the Yellow Card scheme is and when it should be used.

Introduction

In England, more than 1 billion items are prescribed each year in primary care and more than 1 million people are taking ten or more medicines for longer-term conditions. Almost half of these patients are aged 75 years and over1. While adverse drug reactions (ADRs) can be experienced at any age, as the population ages and more people receive treatment for longer term conditions, exposure to medicines and their side-effect profile increase and can cumulatively lead to harm2. The incidence of ADR hospitalisation in older people has been estimated at 8.7%3.

An ADR is defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as “a response to a medicinal product that is noxious and unintended, where a causal relationship between the medicinal product and adverse event is either known or strongly suspected”. ADRs may arise following the use of a medicinal product within or outside the terms of its marketing authorisation, or by overdose, misuse, abuse or medication errors or from occupational exposure3.

Results from one study showed that 16.5% of unplanned hospital admissions resulted from ADRs, with polypharmacy in older people being a major cause4. This not only has negative implications for patient health but also has been estimated to cost the UK health system £380m a year3.

ADRs have the potential to impact patients’ quality of life and can cause patients to lose confidence in the health system if the ADR is not dealt with in a timely manner. They have the potential to mimic disease, resulting in unnecessary investigations and delays in getting the right treatment; therefore, it is important that ADRs are investigated and responded to in a timely manner to promote continuation of treatment.

It is important that patients are part of a shared decision-making process and should receive appropriate information about medicines that may benefit them, how these medicines work, treatment expectations and what to do/who to contact if side effects are experienced.

Classification of ADRs

ADRs have traditionally been categorised as ‘Type A’ or ‘Type B’ (see Box 1)3. Type A are more common than Type B and account for 80% of all ADRs3.

Box 1: Classification of ADRs

- Type A (pharmacological/augmented) result from exaggeration of a drug’s normal pharmacological action when given at the usual therapeutic dose. They are dose dependent and generally reversible on either reducing the dose or withdrawing treatment (e.g. dry mouth with tricyclic antidepressants);

- Type B (idiosyncratic/bizarre) cannot be predicted from the known pharmacology of the drug. They are less common and may only be discovered for the first time after a drug has already been made available for general use (e.g. skin rash with antibiotics).

Other types of ADR include:

- Type C (continuing reactions) persist for a long time, an example of this would be osteonecrosis of the jaw with bisphosphonates;

- Type D (delayed reactions) can become apparent sometime after use of the drug, this makes them difficult to detect (e.g. leukopenia occurring up to six weeks following use of some chemotherapeutic agents);

- Type E (end-of-use reactions) occur on withdrawal of a drug (e.g. insomnia, anxiety following the withdrawal of benzodiazepines).

The MHRA Yellow Card scheme

The Yellow Card scheme is a system used to record adverse incidents involving medicines and medical devices in the UK5. It allows the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to monitor all healthcare products in the UK to ensure patient safety and the safety of staff who may handle the medicine. The Yellow Card scheme encourages reports relating to suspected ADRs for all medicines, including:

- Vaccines;

- Blood factors and immunoglobulins;

- Herbal medicines;

- Homeopathic medicines;

- All medical devices available in the UK market;

- Defective medicines;

- Fake or counterfeit medicines/medical devices;

- Nicotine-containing electronic cigarettes and refill containers5.

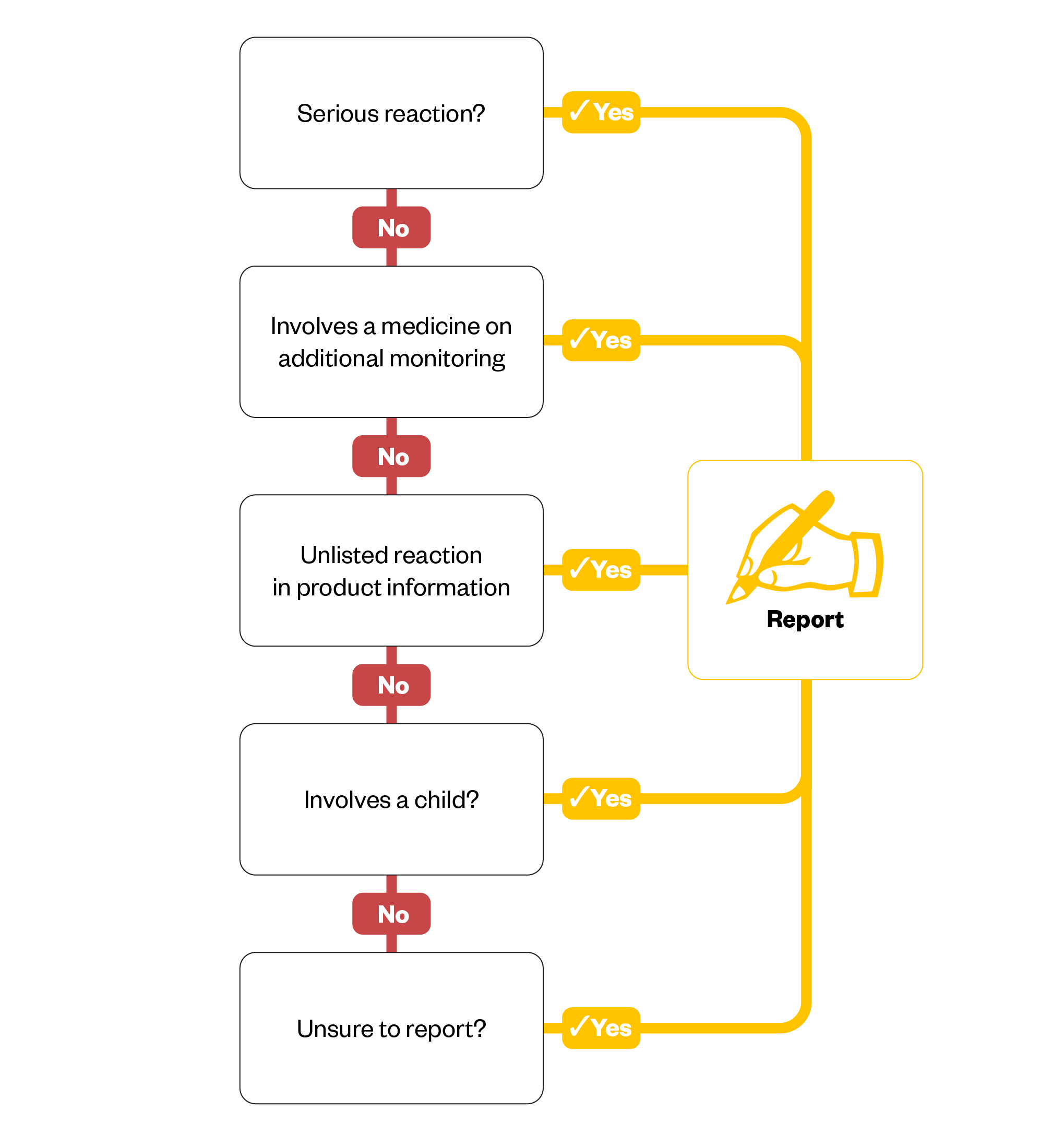

The Figure below outlines when Yellow Card reports should be completed5.

It is important to report all ADRs, even if they are well recognised; this is because reports can influence the information provided in the summary of product characteristics relating to the frequency of reactions. Specific areas of MHRA interest are explained in the following sections.

Children and older adults

Children are at increased risk of ADRs because they react differently to medicines owing to pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic differences. For example, the liver and kidneys in a child may not be fully developed, which will affect how the child metabolises and excretes the medicine6. Drugs used in children are not as extensively tested and could be used off label. In some cases, medicines may contain excipients (including alcohol) to which children react differently6.

Older individuals may be more susceptible to developing reactions as they may metabolise medicines less effectively and be more sensitive to their effects6.

Biological medicines

There is a known complexity with biologics as they are fundamentally different to standard chemical medicines. Biologics can be composed of sugars, proteins or nucleic acids, or a complex combination of these substances. They may be living entities, such as cells and tissues. Biological medicines, such as vaccines, are among the most important medicines in preventing diseases and play a huge role in global healthcare; therefore, the MHRA is interested in understanding more about these medicines and ensuring that patients receive biological medicines of the highest quality6.

Rare or delayed drug effects

ADRs can appear months or even years after drug exposure6. Rare or delayed effects can still be identified when a medicine has been available for many years. For example, Reye’s syndrome was first associated with aspirin 80 years after it was first marketed6. This information then led to a safety alert whereby healthcare professionals were advised against giving aspirin to children and young people aged under 16 years as it was potentially fatal6.

All established drugs and vaccines are continuously monitored under the Yellow Card scheme, but this is only effective if the data is reported. Even if there is a slight suspicion/ potential association, ADRs should always be reported.

Congenital anomalies

Some medications can cause congenital disorders. If a baby is born with a congenital abnormality, it could be a result of an ADR related to a medication. An example is the foetal malformations associated with exposure to valproate6. Reporting on these congenital anomalies led to the development of a national patient safety alert, which required strict controls on the use of this medication. Alerts such as this are important to mitigate the risk of congenital disorders caused by ADRs6. For more information, see ‘Congenital heart disease: an overview’.

Herbal remedies

Only a small proportion of herbal remedies are licensed for use6. It is important that any suspected ADRs to licensed and unlicensed herbal products are reported to ensure the safety of patients who may use such products. Herbal medicines have active ingredients that have the potential to interact with other medicines, as well as the ability to cause clinical effects in patients. The regulation behind these products is somewhat varied so it is extremely important to understand patient experience with these medicines so that the MHRA can identify new safety issues and risks6.

Suspected ADRs

When an ADR is suspected, it is important to first determine when the ADR started, if there is a relationship with a change of dose of a particular medicine or if it is related to the introduction of a new medicine3. Other possible causes (e.g. food intolerances, bites, stings, viral infections or exposure to other possible irritants such as soaps/plants) should be considered.

The following steps should be taken:

- A thorough review of the patient’s drug history, allergies and any previous ADRs the patient has reported;

- Review the adverse effect profile of the drug and consider if the suspected signs and symptoms are in line with this profile;

- It is important for a clinician to assess the nature and severity of the reaction to determine if urgent action is needed, such as referral to A&E, or whether the person can be managed in the community via referral to a local community pharmacy, such as in the management of a local rash following use of a new medicine. More complex ADRs would benefit from being managed by the GP or practice team3.

Recognising adverse drug reactions

ADRs can manifest with varying severity, presenting as both mild and severe reactions. Examples of mild ADRs include nausea, headaches, dizziness and rashes, while more severe reactions might involve anaphylaxis, kidney failure or neuropsychiatric effects3. The ability to identify and report side effects is crucial, because medications that cause similar presentations may vary greatly in severity. For instance, a rash caused by amoxicillin is generally non-harmful and transient, whereas a rash associated with lamotrigine can indicate a severe reaction, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, which requires immediate cessation of therapy7.

Guidance from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society emphasises the importance of comprehensive patient counselling in the recognition and reporting of ADRs. Many patients may not identify ADRs unless they are explicitly discussed with them8. Open communication is essential in helping patients identify any side effects they might experience. It is important to know what medications a patient is taking to identify drug–drug or drug–supplement interactions and clarify any ADRs they may be experiencing8.

In inpatient settings, where patients have direct access to healthcare staff, questions should be asked to inquire about any unusual symptoms that might indicate an ADR. This can be approached by asking ‘Can you tell me about any symptoms/side effects you have experienced since you have started [medication name]? You may then follow up by asking for some more details i.e ‘Can you describe the symptom in more detail? When did it start? How severe is it?’

It is recognised that discussing potential ADRs with the patient prior to commencement of therapy may lead to heightened concern or reduced medication adherence. With this in mind, the importance of transparency and discussing treatment expectations with the patient can mitigate the risk of treatment non-adherence9.

Awareness of ADRs and knowing who to contact can empower patients, alleviating concerns that often lead to non-adherence. When patients are well informed, they feel equipped to manage their medications safely, reducing unnecessary discontinuation3. This proactive approach not only enhances adherence but also minimises the risk of future hospital readmissions and disease progression linked to medication mismanagement3.

While it may be unrealistic to have in-depth discussions about ADRs for every patient, prescribers and pharmacy teams should consider the risk of ADRs when initiating or screening medications in particular medicines associated with a high-level risk or those that require therapeutic drug monitoring8. This involves evaluating patient risk factors, including age, genetics, allergies, and organ function, alongside considerations of the drug’s pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, route of administration, duration of use and starting dose8.

What happens after ADRs have been identified?

Once ADRs are identified, the clinical team — guided by NICE guidelines, the BNF and clinical expertise — will determine whether therapy can continue or needs to be altered3,10. Regardless of the decision, it is crucial to review the patient’s medications, as polypharmacy increases the risk of ADRs owing to drug–drug interactions. A medication review may also highlight opportunities to deprescribe or reduce doses of medications that are no longer benefiting the patient.

Routine monitoring and follow-up should be incorporated into patient care to review responses to medications and detect ADRs. Laboratory tests, therapeutic drug monitoring and physical observations can help identify severe ADRs, such as drug-induced liver damage with statins or clozapine-induced neutropenia.

In community pharmacies, commissioned services such as the New Medicines Service and Discharge Medication Service act as an additional opportunity to engage with patients and find out how they are getting on with the medications and potentially raise concerns around ADRs11,12. Accurate documentation of ADRs is essential for future prescribing decisions and ensuring that patients are not re-prescribed medications that previously caused a severe ADR.

Nurses, who spend the most time with patients in inpatient settings, are likely to notice changes in a patient’s presentation, such as oversedation, extrapyramidal symptoms with first-generation antipsychotics, rashes with lamotrigine or constipation with clozapine13. These observations should be raised at local meetings but also reported via local incident management system and Yellow Card reporting.

In March 2013, the Yellow Card Centre in Wales launched the Yellow Card Hospital Champion scheme. This led to an 81% increase in incident reporting in Wales. The initiative also facilitated multiple training sessions to raise awareness of pharmacovigilance and promote Yellow Card submissions to build safety data around medicines14,15.

How can pharmacists access the Yellow Card scheme?

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams can access the yellow card scheme by going online to the MHRA Yellow Card website, by downloading the dedicated Yellow Card app on their phone or device or by using the paper forms available in pharmacies and GP practices. A freephone service is available to all parts of the UK for advice and information on suspected ADRs4.

Challenges and barriers to reporting

A short survey conducted at an NHS trust in London identified some of the main reasons for lower reporting into the Yellow Card scheme; lack of awareness about the scheme (33%) and uncertainty about what constitutes a reportable ADR (25%) were the two main barriers. Therefore, it is important to signpost patients or staff to the Yellow Card site when there is an opportunity to do so. The full survey results can be found in: ‘Yellow Card reporting in East London NHS Foundation Trust’.

How to support patients

Patients should be advised to keep track of how they are feeling after starting a new medication or when the dose of an existing medicine has changed and to report any unusual symptoms to their healthcare provider promptly. This should be included as part of safety netting advice provided to patients at the point of prescribing (see ‘How to provide patients with safety-netting advice’ for more information on this).

The Yellow Card scheme should be discussed during consultations to illustrate the benefits to the patient and how this contributes more widely towards the safety profile of the drug. Patient information leaflets, online platforms and social media campaigns (i.e. World Patient Safety Day) are often used to promote the scheme and raise awareness publicly and this should continue. It is important that additional support is provided to patients with language barriers or cognitive impairments to ensure they can access and use the Yellow Card scheme effectively. The MHRA Yellow Card site currently has an option for those for whom English is not their first language to use the Google Translate application to ensure information is in a format that can be understood by the user4. The use of other technology, such as access to digital patient information leaflets, may also be useful for those with cognitive impairments. Despite this, the most effective approach would be to tailor the communication to individual’s needs by using appropriate language, visual aids and repetition, which may enhance comprehension.

The MHRA has produced a video detailing the patient’s experience and perspective around a particular medication and navigating the system to understand the adverse drug reaction and ongoing reporting.

Conclusion

A multidisciplinary approach is essential when educating patients about identifying and reporting ADRs. ADRs significantly impact medication adherence, making it vital for the healthcare team to collaborate with patients on treatment strategy. This approach ensures that patients are supported in identifying and managing ADRs, ultimately improving medication safety and therapeutic outcomes across various healthcare settings.

Best practice

Medicine safety isn’t just about responding to challenges; it’s about proactive measures and strong partnerships. When these practices are combined, they create an environment where medicines safety becomes a shared responsibility, leading to better outcomes and trust between patients and healthcare teams.

- Patients who are aware of what to expect from their medications are better equipped to notice and report side effects;

- Healthcare providers should ensure that service users understand how to take their medicines correctly, which can prevent overdosing or underdosing;

- Consider the impact of New Medicines Service and Discharge Medicines Service referrals and the opportunity for patients to reflect on their experience with new medicines and community pharmacies to educate patients about ADRs and reporting through the Yellow Card Scheme;

- A multidisciplinary team approach to ADR identification and reporting empowers patients, boosts confidence and possibly reduce readmissions linked to non-adherence.

- 1.Analyse. OpenPrescribing. 2019. Accessed June 2025. https://openprescribing.net/analyse/

- 2.Prescribed medicines. NHS Digital. 2022. Accessed June 2025. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-england-additional-analyses/ethnicity-and-health-2011-2019-experimental-statistics/prescribed-medicines

- 3.Adverse drug reactions. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022. Accessed June 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/adverse-drug-reactions/background-information/health-financial-implications-of-adrs/

- 4.Osanlou R, Walker L, Hughes DA, Burnside G, Pirmohamed M. Adverse drug reactions, multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a prospective analysis of 1 month of medical admissions. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e055551. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055551

- 5.Yellow Card Scheme. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . Accessed June 2025. https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk

- 6.Specific areas of interest for reporting suspected adverse drug reactions. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . Accessed June 2025. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a8008e840f0b62305b88c6e/Specific_areas_of_interest_for_adverse_drug_reaction_reporting.pdf

- 7.Taylor DM, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. Published online December 17, 2021. doi:10.1002/9781119870203

- 8.Getting our medicines right. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Accessed June 2025. https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/setting-professional-standards/polypharmacy-getting-our-medicines-right

- 9.Baryakova TH, Pogostin BH, Langer R, McHugh KJ. Overcoming barriers to patient adherence: the case for developing innovative drug delivery systems. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(5):387-409. doi:10.1038/s41573-023-00670-0

- 10.British National Formulary. British National Formulary. Accessed June 2025. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/

- 11.New medicine service . Community Pharmacy England. Accessed June 2025. https://cpe.org.uk/national-pharmacy-services/advanced-services/nms/

- 12.Discharge Medicines Service. Community Pharmacy England. Accessed June 2025. https://cpe.org.uk/national-pharmacy-services/essential-services/discharge-medicines-service/

- 13.Butler R, Monsalve M, Thomas GW, et al. Estimating Time Physicians and Other Health Care Workers Spend with Patients in an Intensive Care Unit Using a Sensor Network. The American Journal of Medicine. 2018;131(8):972.e9-972.e15. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.03.015

- 14.Yellow Card champion scheme. All Wales Therapeutics and Toxicology Centre. Accessed June 2025. https://awttc.nhs.wales/medicines-optimisation-and-safety/yellow-card-centre-wales/yellow-card-champion-scheme

- 15.Yellow card champions to help increase reporting of adverse drug reactions. The Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2016. doi:10.1211/pj.2016.20200416