This content was published in 2013. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

In short

For patients and clinicians, managing the symptoms of chronic heart failure can be complex and challenging — particularly in older people and those with comorbidities.

Pharmacists, as members of the multidisciplinary team, can support and empower patients with heart failure around matters relating to self-care and medicines management.

Heart failure affects 1–2% of the adult population in the UK with the prevalence rising steeply with age. It is one of the leading causes of emergency medical admissions and readmissions to hospital. Patients with heart failure have a reduced quality of life and many experience severe or prolonged depressive illness.1

The most common causes of heart failure are ischaemic heart disease and hypertension. Other causes include genetic disease of the heart muscle, congenital heart defects, cardiac arrhythmia, alcohol misuse, some cancer treatments and viruses.

The term “heart failure” is used widely and encompasses:

- Left-ventricular systolic dysfunction, also known as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- Right-ventricular failure

- Bi-ventricular failure

Symptom management

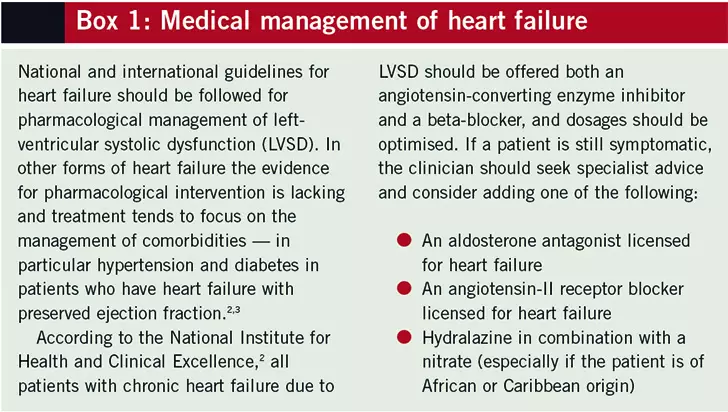

Early and accurate diagnosis of heart failure is crucial for optimal management using evidence-based pharmacological treatment (see Box 1) and implantable devices.

For patients, reducing symptoms of heart failure can have marked effects on quality of life. In clinical trials morbidity benefits are usually assessed by evaluating hospital admissions and readmissions for heart failure or cardiovascular causes. The main symptoms relate to fluid retention which can give rise to:

- An increase in breathlessness, orthopnoea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea secondary to pulmonary congestion or pulmonary oedema

- Peripheral oedema, which can range from mild ankle swelling to gross oedema including abdominal ascites and at times extending to the genitalia and beyond

Managing the effects of fluid overload can be challenging and include the use of diuretics, fluid and salt restriction, daily weighing and education of the patient and carers on ways to recognise and respond early to deterioration.

Diuretic therapy

Despite the widespread use of diuretics there is no evidence of survival benefits from these medicines. Nevertheless, managing the symptoms of fluid overload is essential in all forms of heart failure. Loop diuretics (most commonly furosemide or bumetanide) form the mainstay of treatment, with thiazide diuretics being used alone only in mild cases or in combination with loop diuretics for a synergistic effect in more severe cases.4

It is important to use the lowest dose of diuretic to manage symptoms (preserving renal function in the longer term) and to review the dose of diuretics regularly in line with symptoms, renal function and electrolyte concentrations. However, there will be some patients for whom diuretics become less effective with time and diuretic resistance is a challenge in everyday clinical practice.

Self-care strategies

Like for many other chronic conditions, education in self-care strategies is important for the heart failure patient to maintain health.5 Development of multidisciplinary heart failure services in the UK has been important in ensuring patients learn about heart failure, the trajectory of the condition, its management and how to access professional help when things are starting to deteriorate.6 At Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, this approach has had a positive impact on reducing readmission rates for decompensated heart failure.

Pharmacists can help patients with heart failure by:

- Supporting medication adherence

- Offering lifestyle advice, eg, regular exercise, smoking cessation, fluid and dietary recommendations

- Providing guidance on recognising and responding to symptom deterioration

Information provided can be supplemented by signposting patients to appropriate websites (eg, www.heartfailurematters.org), DVDs and publications (eg, those produced by the British Heart Foundation5). A person-centred approach should be taken, and clinicians should remain aware that patients may experience barriers to self-care, such as depression, anxiety or impaired cognition, which may reduce motivation and adherence.

Salt restriction

Although there is much in the media and medical literature about salt intake and its detrimental effects on health for patients with chronic heart failure, studies supporting sodium restriction are limited. In our experience, patients and carers consider this one of the most difficult aspects of self-management.

The recommended daily intake of salt for adults is 6g (or 2.5g of sodium), which equates to only a teaspoon of salt a day. Advice to guide patients is essential, since there is much “hidden” salt in food, particularly in processed foods (see Box 2).

Strategies to help patients include education on food labelling, increasing awareness of foods to avoid and how to limit salt intake. Practical suggestions include removing salt from the dining table and using herbs, spices and fresh lemon or lime juice as alternative seasonings.

Importantly, patients should be advised to avoid salt substitutes, which usually contain potassium salts, due to the risks of hyperkalaemia (particularly in the presence of renal impairment or with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or aldosterone antagonists).7

Fluid intake

There is a paucity of evidence on the restriction of fluids for heart failure patients and current guidelines advise that routine fluid restriction is of no benefit except in patients with severe heart failure or those with concomitant hyponatraemia.3

Nonetheless, it is important to establish each patient’s usual fluid intake because many (particularly elderly patients) do not have a high fluid intake. It is good practice to review the need for fluid restriction on an individual basis and advise according to severity of symptoms, body mass index, weather conditions, electrolyte levels and presence of diarrhoea, vomiting or fever.

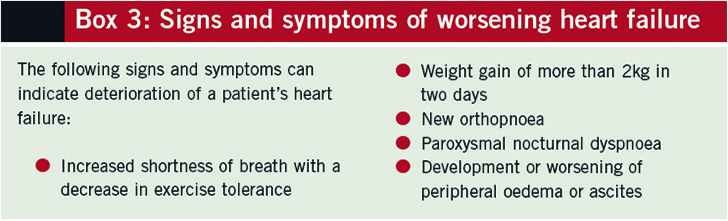

Recognising deterioration

Patients require education on recognising the signs and symptoms of deterioration (see Box 3) and the daily recording of weight is central to this. Such signs and symptoms tend to indicate fluid retention — adjustment of diuretic dose along with the monitoring of renal function can often resolve the situation or prevent further deterioration.

Over-diuresis may also occur alongside fluid and electrolyte loss and risk of deterioration in renal function. Early signs include excessive urination, weight loss, tiredness, muscle weakness, dizziness and dry skin. Patients who are new to diuretic therapy, those with a recent increase in diuretic dose and those with diarrhoea and vomiting should be particularly vigilant; early recognition, with diuretic adjustment and renal function monitoring, is crucial.

Patients should also be given advice on what to do if they experience:

- Chest pain

- Acute shortness of breath

- Dizziness

In addition, patients should be made aware that their condition can destabilise if they develop an infection.

Exercise

It is a misconception that patients with heart failure will not be able to participate in exercise programmes. Physical conditioning through exercise has been shown to increase exercise tolerance, improve health-related quality of life and reduce hospital admissions among patients with heart failure. The European Society of Cardiology recommends regular aerobic exercise, ideally as part of a multidisciplinary care programme, to improve functional capacity and symptoms.3

Signposting the patient to local programmes designed for cardiac patients can improve uptake and ongoing participation.

Managing medicines

Pharmacists should be alert to medicinesrelated issues among heart failure patients, especially those prescribed complex regimens. It may be necessary to:

- Adapt labelling for visually impaired patients

- Simplify treatment regimens

- Engage family members or care providers to assist with administration

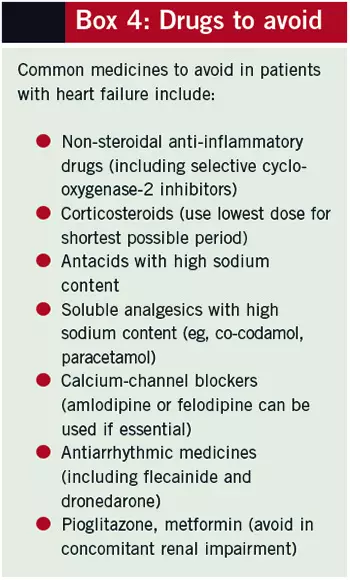

Patients should be aware that any change to their medicines, or the addition of a new treatment (for short-term or ongoing use), may require closer monitoring of their heart failure. Box 4 lists some common medicines to be avoided or used with caution for patients with heart failure. Of particular note is the detrimental effect of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs, which can cause fluid retention and renal impairment with resulting decompensation of heart failure that can lead to hospital admission.

Community pharmacists are well placed to support the patient in the longterm use of medicines and to help identify those patients who are experiencing difficulties.

NOTE

Clinical Pharmacist PRACTICE TOOLS do not constitute formal practice guidance. Articles in the series have been commissioned from independent authors who have summarised useful clinical skills.

References

- National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. National heart failure audit April 2010 – March 2011. www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/heartfailure/additionalfiles/pdfs/annualreports/annual11.pdf (accessed 5 October 2012).

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic heart failure: management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. August 2010. www.nice.org.uk/cg108 (accessed 5 October 2012).

- European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. European Heart Journal 2012;33:1787–1847.

- Jentzer JC, DeWald TA, Hernandez AF. Combination of loop diuretics with thiazide-type diuretics in heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010;56:1527–34.

- British Heart Foundation. Heart failure publications. www.bhf.org.uk/publications/publications-searchresults.aspx?m=simple&q=heart+failure (accessed 5 October 2012).

- Lainscak M, Blue L, Clark AL, et al. Self-care management of heart failure: practical recommendations from the patient care committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Heart Failure 2011;13:115–26.

- British Heart Foundation. Salt publications. www.bhf.org.uk/publications/publications-search-results.aspx?m=simple&q=salt (accessed 5 October 2012).