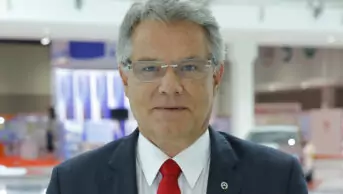

Courtesy of David Palopoli

Frank Palopoli, a chemist who discovered clomifene, the drug which revolutionised fertility treatment for anovulatory women, died on 6 August 2016 at the age of 94.

Palopoli, the eldest of three sons of immigrants from southern Italy, began working for the William S Merrell Company (later Merrell-Dow) in 1950 as a research assistant and retired in 1990 as global director of chemical development.

In 1956, he and colleagues synthesised the substance now known as clomifene citrate. A patent application for the compound was made 1957 and granted in November 1959.

In 1961, the first results of clinical testing in humans noted in JAMA that it was “heartening to find a drug which holds much promise of inducing ovulatory-type menses with considerable regularity in anovulatory women”.

An editorial in the BMJ, published in October 1962, found the results “of interest”. Clomifene, also known as Clomid, went on the market in 1967. It is now on the World Health Organization’s list of essential drugs.

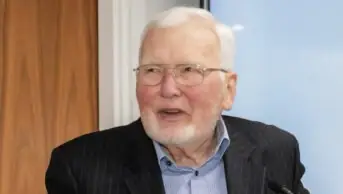

Tony Rutherford, a member of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority — the UK’s independent regulator overseeing the use of gametes and embryos in fertility treatment and research — and former chair of the British Fertility Association, says: “It’s a great drug and the mainstay of inducing ovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. It has never been overtaken by anything else in that field. It works quickly and it’s cheap.”

Clomid produces ovulation rates of 60–85% and pregnancy rates of 30–40% “so not that different from the general population,” said Rutherford, consultant in reproductive medicine and gynaecological surgery at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS trust.

Palopoli, who died of heart failure in Montgomery, Ohio, United States, was born in Pittsburgh on 19 February 1922. His father, Francesco, a steelworker and cobbler, had emigrated to the US from Calabria in 1910 and his mother, Pauline (di Mauro) had emigrated from Sicily, Italy, in 1921.

His father moved to Pittsburgh after his shoe repair shop in New York was blown up in a protection racket. As well as working in the Pittsburgh’s steelworks, he also owned a cobbler shop where he made and repaired shoes, with the family living behind the shop. The family spoke only Italian at home but Frank learnt English on the streets. In order to bring some money into the home he worked as a pinsetter in a bowling alley and for an Italian grocer.

Frank attended Central Catholic High school in Pittsburgh, and then the city’s Duquesne University where he obtained a BSc in 1943 and MSc in 1948. He also studied organic chemistry at Purdue University in Indiana, completing all the course work (but not thesis) required for a PhD in the industry. However, his work would have earned him multiple PhDs in chemistry. He worked in the steelworks to help pay his way through college and also sang in bars. During the war he served in the US Navy. He married Margaret D’Alfonso in 1944 and they had five children.

He never really received acclaim for what I consider a significant contribution to the welfare of mankind

Apart from an interlude at Merrell’s sister company, The National Drug Company in Philadelphia, where he was director of clinical research from 1963 to 1970, he spent his career at Merrell in Cincinnati, Ohio. He and colleagues also synthesised MER-29, the first cholesterol-lowering drug, which was introduced in 1959.

He travelled extensively in Europe overseeing drug development and authored or co-wrote some 60 papers in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry and the Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry.

In 2009 Palopoli’s children endowed a professorship in the science department of La Salle University, Philadelphia, to honour their father’s contribution to drug development. Palopoli’s son, Frank C. Palopoli said: “He never really received acclaim for what I consider a significant contribution to the welfare of mankind. Thousands and thousands of families are able to have children who might not have. Clomid is so positive in encouraging life that it is certainly worthy of celebration.”

Frank C. Palopoli believed his father’s interest in chemistry was inspired by the present of a chemistry set when he was a child, and encouragement from a high school teacher.

Another son, John Palopoli, a physician who lives in Louisiana, said that his father was a modest man and conscientious mentor to his staff at Merrell. “He took them under his wing. They loved him,” he said.

John Palopoli added that his father rarely referred to his achievements.

“He was polite and gracious when approached by someone who, by chance, discovered he was the scientist who discovered Clomid allowing them to have a son or daughter they would refer to as their ‘Clomid baby’. Dad would accept thank yous and hugs, but never let it go to his head.”

Palopoli had a lifelong love of singing — and musicals — and sang in his church choir until he was 90.

Speaking at his father’s funeral in August, John Palopoli said: “Dad was an explorer. He loved the adventure that went with travel and as a scientist made discoveries that changed the world.”

Palopoli is survived by four sons and a daughter. His wife predeceased him in 2006 at the age of 84.

You may also be interested in

Robert Twycross (1941–2024)

Nina Barnett (1965–2023)