studiomode / Alamy Stock Photo

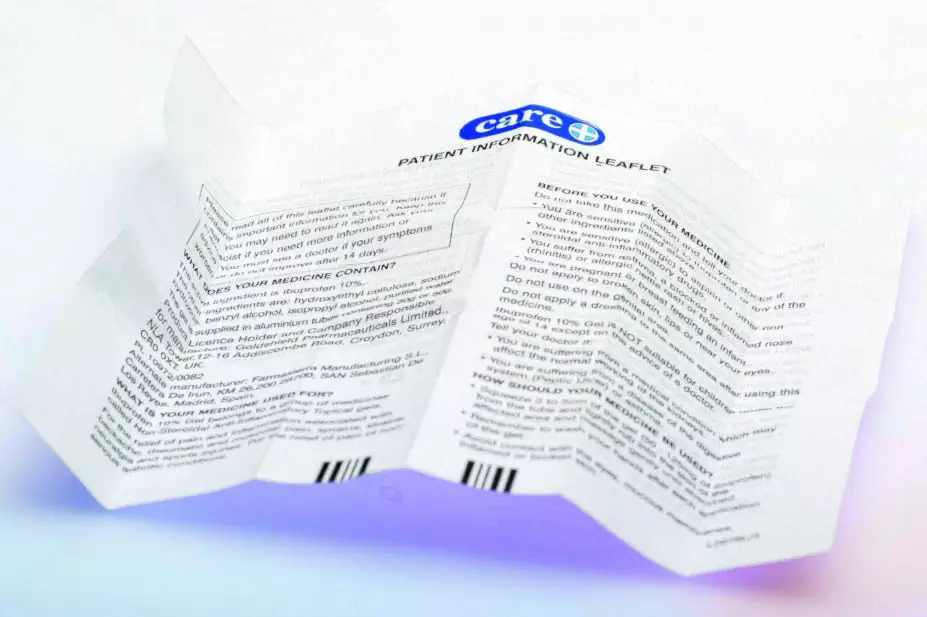

Most people, including some healthcare professionals, probably think that patient information leaflets (PILs) are screwed-up pieces of paper with small print and unintelligible, scary text. In fact, they contain specific information about medical conditions, doses and side effects, and are packed with medicines to give the user information about the product. All licensed medicines need to carry such a leaflet.

Since 2005, action has been taken to improve them, with the impact of EU legislation (Directive 2004/27/EC) requiring that they “reflect the results of consultations with target patient groups to ensure [they are] legible, clear and easy to use”[1]

. As a result, pharma companies have implemented ‘user testing’ of PILs — where lay people are asked to test the PILs, and any problems are identified and addressed.

Recent reports from the European Commission (EC) and the Academy of Medical Sciences have made recommendations for improvement of PILs[2],[3]

.

The EC report ‘Study on the package leaflets and summaries of product characteristics of medicinal products for human use’ concluded that patients’ comprehension of the PIL and its readability can be improved, and that the language used is often too complex and the design and layout are not always user-friendly[2]

.

In its report ‘Enhancing the use of scientific evidence to judge the potential benefits and harms of medicines’, the academy said there was too much focus on the potential side effects of medicines on PILs and not enough on their benefits, and there was too much medical jargon.

Criticisms about the usability of PILs are not new. But there are few comprehensive, reliable and available resources for patients about their medicines — and the PIL is one of the few that do exist.

User testing

Under user testing, the testers provide feedback on what is wrong with a PIL, applying expertise in information writing and design to make improvements. The PIL is then tested again. Crucially, there are two parts to the interview: the first determining whether people can find and understand the key points of information; the second asks them open questions about what they did and did not like about the leaflet[4]

.

These responses to the open questions are particularly useful because the participants’ views are informed by their having had to use the PIL to answer the questions in the first part of the interview. This differentiates the process from one in which patients (often ‘expert patients’ — people who have the confidence, skills, information and knowledge to play a central role in the management of life with chronic diseases — from patient groups) are simply asked for their views on health information.

It is only the man or woman ‘in the street’ who can tell us if the leaflet is fit for purpose for ordinary people

It is an important aspect of user testing that ‘real’ people do the testing, not expert patients. Expert patients are important in providing strategic advice, but such people are not appropriate for testing the information itself. It is only the man or woman ‘in the street’ who can tell us if the leaflet is fit for purpose for ordinary people.

The key improvements to arise from user testing since its implementation relate to the wording and the layout. Both are equally important, and a leaflet will just as likely fail a user test because people cannot find the information as not understanding it if they do find it. Not only has the process of user testing improved PILs directly, but it has also led to a change in attitude of many of those involved. It has been a catalyst for convincing people, notably those in the pharma industry, that good patient information does matter, and is worthwhile addressing.

What further improvements are needed?

User testing has resulted in improvements to PILs, but there are still issues that need to be addressed to maximise their benefits. This was reflected in the decision by the EU to commission the report on the ‘shortcomings’ of PILs — undertaken by the universities of Utrecht and Leeds[2]

. This involved an extensive literature search and a Europe-wide stakeholder survey, including patients and the public. Some of the key recommendations of this report include:

- Reformulate the guidance for PILs to include more on the principles of good information design. Good design and layout are central to enabling the reader to find their way around — and our experience is that a PIL is as likely to perform badly in a user test because readers cannot find key information rather than not being able to understand information.

- Further strengthen input from patients, and, in particular, to make user testing more iterative (testing can be undertaken mechanistically, without a focus on the iterative ‘test-improve-test’ approach).

- Examine the potential for electronic options in the future. This is something that we should take seriously now. But in the medium term the consensus is that we will continue to need a hard copy.

- Explore the possibilities for the PIL to be part of the care process, rather than being standalone — hence the need for more pharmacist input.

Do we need headlines for PILs?

There is a sister report which specifically addressed the idea of a key information section at the start of a PIL (also called a ‘headline section’). This is a listing of five to nine bullet points which summarise the most important points related to that medicine. Research at Leeds has shown that lay people very much like the idea of a headline section but do not necessarily use it when answering questions on the PILs[5]

. However, there appears to be considerable face value in the idea of a key information section, and the report called for more experience and evidence to be gathered — through testing examples of key information sections.

There appears to be considerable face value in the idea of a key information section

The UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has championed the idea of headline sections, notably in its influential publication ‘Always read the leaflet’[6]

— and has sanctioned this approach for selected leaflets in the UK. Indeed, the MHRA has been a significant player in pressing for improvements in leaflets at EU level and this was noted in the Academy of Medical Sciences report. They also co-funded a PhD student at the University of Leeds researching the ideas of a headline section and including benefit information in PILs.

Information on benefits

Perhaps the Achilles heel of PILs is that they focus on the ‘bad things’ rather than balancing the possible negative effects with the potential benefits of medicines. If people are going to make informed decisions about whether a medicine is right for them, they need both aspects — ideally expressed in similar terms (the recent Academy of Medical Sciences and EU reports both called for this).

The academy noted that the ‘research community has honed highly effective methods for determining the benefit and harms of medicines’ but, unfortunately, we do not yet know how to express this in plain language to patients.

The work of the Leeds/MHRA PhD student included giving numerical information about benefit to people taking statins, for example: “If 17 people like you take this medicine over the next 5 years, one of them will be prevented from having a heart attack or stroke”. A key finding was that patients were surprised by the perceived lack of benefit — and this ‘number needed to treat’ type of benefit expression was found to be difficult for many people[7]

.

Another barrier to providing benefit information is that you have to decide which data on benefits you use, such as which trials and which endpoints. Also, it is hard to be specific about benefits in numerical terms than it is about side effects because the indications for a single drug may vary widely. Equally, a single condition may depend on a number of medicines — each of which has a separate leaflet.

Pharmacist intervention

PILs may not be perfect, but they can still make a difference. Firstly, our research suggests that the majority of people do look at a leaflet the first time they receive a medicine, but not very often after that. Much of the public and professional view of PILs may be related to the old-style PILs that we saw in the past — before user testing and the new regulations resulted in improvements. This means a public education campaign is needed along the lines of ‘have a look at your new leaflets’.

Secondly, a pharmacist or pharmacy technician has the opportunity to talk to a patient about their medicines each time they are dispensed (although recent research suggests that this happens only in a minority of cases)[8]

. They could focus this discussion around the PIL — taking it out of the box and using it as an aide-mémoire — pointing out the key points which are most relevant to that patient. With such an approach, the patient may see more value in the leaflet, and it also helps the pharmacist to include all the key points and tailor their discussion to the individual patient.

Theo Raynor is professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Leeds, and co-founder and academic adviser to Luto Research, which develops, refines and tests health information materials.

References

[1] European Parliament and the Council of the European Union: amended by directive 2004/27/EC of the European Parliament and of the douncil of 31 March 2004 amending directive 2001/83/EC on the dommunity code relating to medicinal products for human use. Official Journal L 136. 2004. Available at: http://www.gmp-compliance.org/guidemgr/files/DIR_2004_27_EN.PDF (accessed December 2017)

[2] Raynor DK, van Dijk L, Monteiro SP et al. Study on the package leaflets and summaries of product characteristics of medicinal products for human use. European Commission 2015. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/committee/75meeting/pil_s.pdf (accessed December 2017)

[3] Academy of Medical Sciences. Enhancing the use of scientific evidence to judge the potential benefits and harms of medicines. Available at: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/44970096 (accessed December 2017)

[4] Raynor DK. User testing in developing patient medication information in Europe. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2013;9(5):640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.02.007

[5] Dickinson R, Raynor DK, Knapp P et al. Do patients use a headline section in a leaflet to find key information about their medicines? Findings from a user-test study. Ther Innovation & Regul Sci 2016;50:581–591. doi: 10.1177/2168479016639080

[6] Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Always read the leaflet: getting the best information with every medicine: report of Committee on Safety of Medicines Working Group on patient information. The Stationary Office. 2005. Available at: http://www.paint-consult.com/fileadmin/editorial/downloads/guidelines_behoerden/packungsbeilagen/MHRA_Always_read_leaflet_2005.pdf (accessed December 2017)

[7] Dickinson RJ, Raynor DK, Knapp P et al. Providing additional information about the benefits of statins in a leaflet for patients with coronary heart disease — a qualitative study of the impact on attitudes and beliefs. BMJ Open 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012000

[8] Rivers PH, Waterfield J, Grootveld M et al. Exploring the prevalence of and factors associated with advice on prescription medicines: a survey of community pharmacies in an English city. Health & Soc Care in the Community 9 May 2017. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12451