Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this feature article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/wuhan-novel-coronavirus

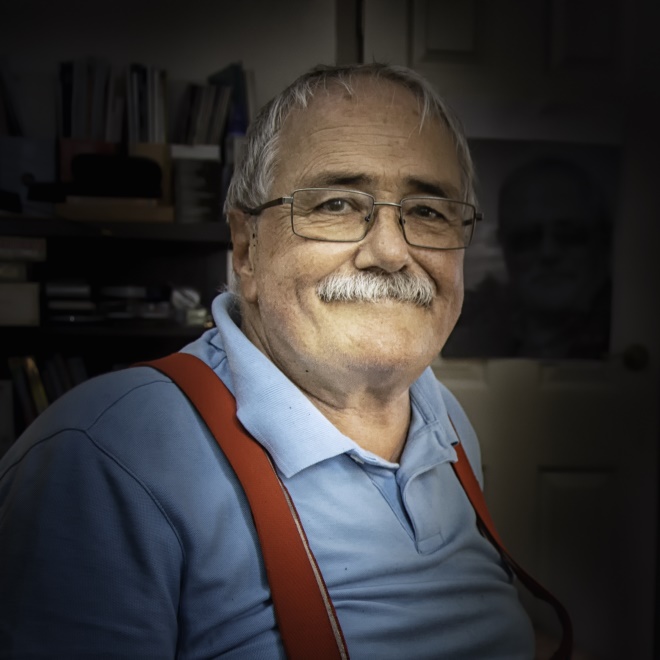

bob dunkley

Bob Dunkley, semi-retired community pharmacist

At 70 years of age, male and with type 2 diabetes, community pharmacist Bob is in a high-risk group and, in March, chose to self-isolate at home rather than continue with his weekly locum shift at an independent community pharmacy in Bradford. “One week I was doing my usual locum shift and the next week COVID-19 descends, and my life is in danger,” he recalls.

But he has not been sitting around with his feet up. He runs a support group for pharmacists who are recovering from alcohol addiction, which has been in demand during the pandemic. “It has been a time of great mental strain, and if you’re already in a very fragile state, from drug or alcohol use, you’re not in a very good place,” he explains.

Bob returned to work as a locum in August. He admits that 2020 has been the most memorable of his 50 years within the profession. “Over the years… there’s been no major upsets. There’s been peaks and troughs, of course … but COVID-19 is unique,” he says.

Mark Borthwick, consultant pharmacist in critical care

When the first surge of COVID-19 cases hit, Mark, consultant pharmacist in critical care at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, was at the sharp end. “Patients surged out of our prepared area and into the rest of ICU, and then into a cardiac critical care area, all within a week. Our initial plan only lasted 36 hours. It was unbelievably stressful.”

The pharmacy introduced a near patient intravenous preparation area for COVID-19 patients. “We were working a 12-hour shift system, three to four days a week,” says Mark, who lives with his wife Claire – a hospital pharmacist – four children and three dogs.

As cases rise again, Mark says there is a sense of fatigue. “The first time nobody quite knew what was happening… and in one perverse sense, perhaps it was energising to have to deal with a complete redesign of the services. But now, we need to put in place what we’ve learned, and deal with business-as-usual alongside this. We can see we’re in for the long haul. But we all have a job to do and we just need to get on with it.”

Osariemen Egharevba-Buckman, MPharm student

Osariemen, a third-year student at Medway School of Pharmacy, says there was uncertainty when universities first closed their doors in March. “It took [the university] a week or two to … figure out how it was all going to work.” Osariemen moved back to London, where she shares a house with her parents and two siblings.

Online learning for Osariemen’s course took the form of recorded lectures but there was confusion about whether exams would go ahead. “It was very nerve-racking because I didn’t know if I should be revising.”

Two of her uncles contracted COVID-19 during the early part of the pandemic, which Osariemen says “was very scary” and made it difficult to focus on her studies.

Osariemen returned to university in September, but online learning has continued, which she finds difficult. She also feels disappointed that she is missing out on face-to-face teaching and practice placements, as well as the social aspects of university life. “When you go to university, you go to the library, you go to societal events, and you go to lectures, and in between you have a catch up — all those things have kind of been lost. At times, it’s lonely.”

Navinder Singh, provisionally registered pharmacist

Navinder, a provisionally registered pharmacist, was in the middle of preregistration training in an independent community pharmacy in Huddersfield when the pandemic first hit.

“It started quite slow … but I remember there being a sense of impending doom,” he recalls.

Two weeks later, the pharmacy began to feel the impact. “We had to limit entry and serve at the door as there was such huge demand.” This led to longer working hours: “We started to stay for one to two hours after closing each week to tidy up. And we would use half of our lunch break to disinfect the pharmacy. Sometimes when I got home, I didn’t have the energy to do anything. I would just have a quick snack and go to bed.”

Although Navinder had initially planned to study for a PhD in pharmacology, this was curtailed and, instead, he gained experience at the pharmacy as well as working for a preregistration training provider. He is feeling optimistic about the future and hopes to pursue a role in a GP practice.

Karen Newman, care home pharmacist

Before the pandemic hit, Karen, senior clinical pharmacist in the Medicines Optimisation in Care Homes team at Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust, spent her days in the office she shares with her team or visiting one of 280 care homes.

But in March, life changed dramatically when care homes shut their doors. “One week I was visiting a care home … and then the following week I was left wondering what I was doing next.” Karen had to get used to a different way of working, based at her home, which she shares with her police officer husband and two grown up sons.

To begin with, Karen was firefighting, but she has now settled into a routine in which she provides medicines reviews via telephone and video calls. “I do miss the patient contact. You don’t go into a job like this without actually liking patients.” The lack of day-to-day contact with her colleagues has also been isolating: “The team is there for you to lean on, and that is not the same when you are at home.”

You may also be interested in

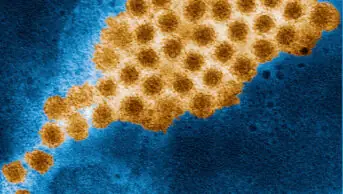

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control