Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

The UK government announced on 16 September 2024 that it has ordered more than 150,000 doses of mpox vaccine to help ensure the UK is prepared for any cases of a new clade of the virus that may enter the country.

“No cases of clade I mpox have been detected in the UK, but we are taking steps to ensure the country is prepared with a robust vaccination programme that protects those who may be at high risk,” said health secretary Wes Streeting.

The announcement follows a rapid rise in the number of cases of a new mpox strain, which led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC)” on 14 August 2024, the second related to mpox in two years.

In a statement issued alongside the PHEIC declaration, Dimie Ogoina, WHO committee chair and infectious disease physician at the Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria, said: “The current upsurge of mpox in parts of Africa — along with the spread of a new sexually transmissible strain of the monkeypox virus — is an emergency, not only for Africa, but for the entire globe.

“Mpox, originating in Africa, was neglected there, and later caused a global outbreak in 2022. It is time to act decisively to prevent history from repeating itself,” he added.

The latest data — published on 31 August 2024 by the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention — show that there have been over 24,000 mpox cases reported in Africa since the beginning of 2024, including 18,737 suspected cases, 5,265 confirmed cases and 617 deaths. More than 90% of these cases originated in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

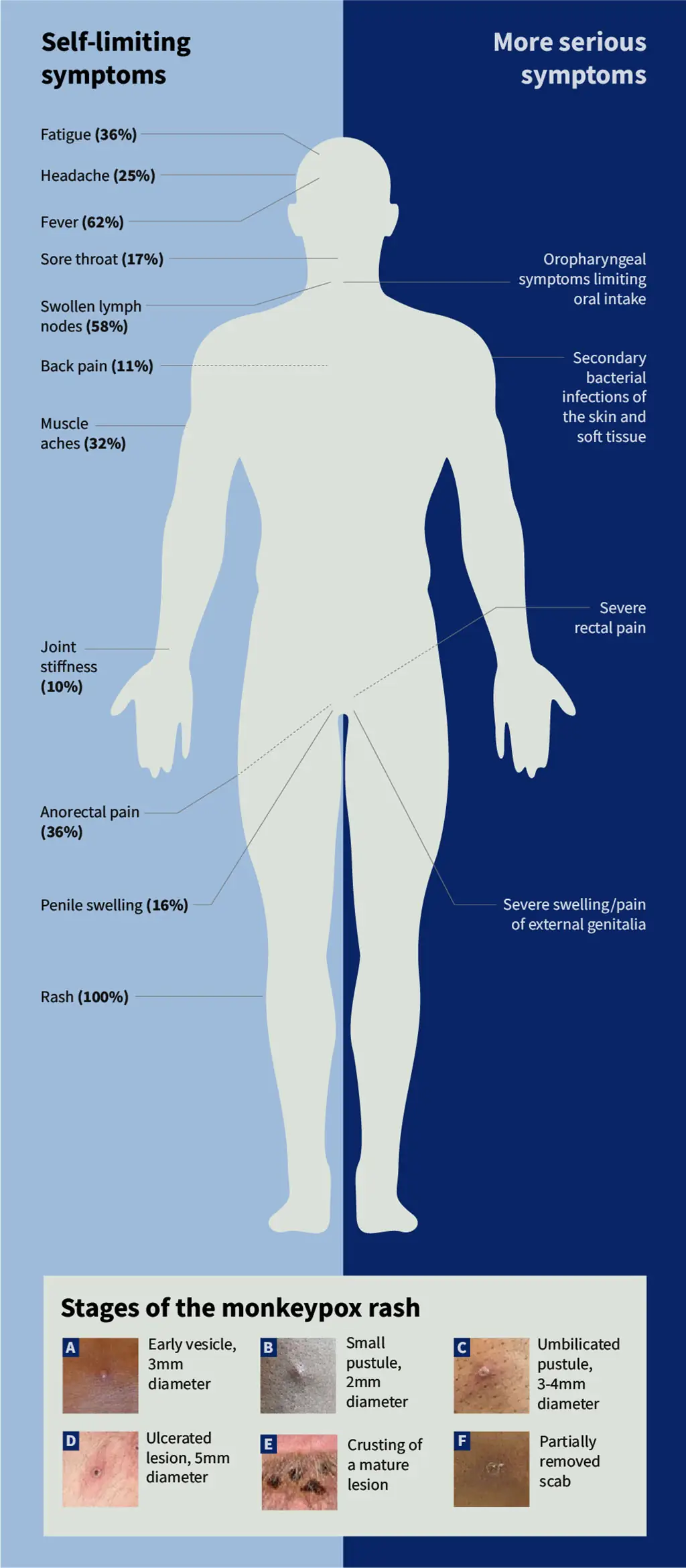

Mpox — formerly known as ‘monkeypox’ — is a virus from the same family as smallpox and presents with a rash often beginning on the face or genital area, which may be mild and localised, but can also be severe and disseminated (see Figure 1 for symptoms, see Box 1 for more information on mpox).

Box 1: What is mpox?

- The mpox virus is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus, of the orthopoxvirus genus. The virus was initially discovered in monkeys in a Danish laboratory in 1958, but can infect various animals, including rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats and dormice;

- Mpox spreads mainly through close contact with someone who has the virus. This includes skin-to-skin (e.g. touching or sexual intercourse), mouth-to-mouth (e.g. kissing), or face-to-face (e.g. talking or breathing close to one another). It can also be passed on via contaminated materials, animals or during pregnancy;

- Anyone can catch mpox; however, people with multiple sexual partners are at higher risk of acquiring the virus;

- Based on available data from both clades, children aged under 15 years are considered at risk of severe disease, with children aged under 5 years at highest risk;

- Symptoms of mpox usually begin within one week but can start up to 21 days after exposure (on average 6 to 13 days), with initial clinical presentations of fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy and headache (see Figure 1) and typically last 2 to 4 weeks. Symptoms may last longer in those who are immune compromised;

- Clinical diagnosis of mpox can be difficult because other conditions can look similar. The preferred laboratory test for mpox is detection of viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction [6]. Rapid testing for all mpox strains is available in the UK;

- Treatment of mpox is mainly supportive — treating the rash, managing pain, and preventing complications;

- Antiviral medicines, such as cidofovir and tecovirimat, have been used for those with or at high risk of severe disease; however, at present there is no proven effective antiviral treatment for mpox, leaving vaccination as the focal point in managing the outbreak.

The Pharmaceutical Journal/Photographs: courtesy of the UK Health Security Agency

There are two major genetic groups (clades) of the virus: clade II mpox (formerly known as ‘West African clade’); and clade I mpox (formerly known as ‘Central African or Congo basin clade’), which is considered to be more severe.

Historically, fatality rates for clade I mpox have been as high as 10% in unvaccinated individuals, but recent outbreaks have seen lower rates of 1–3%. According to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), differences in the features of past outbreaks, such as population groups affected, make it hard to draw a firm conclusion.

These clades are further classified into subclades – clade Ia and Ib and clade IIa and IIb. The clade IIb strain was responsible for the global outbreak in 2022.

The new ‘clade Ib’ mpox virus first emerged in September 2023 in the east of DRC and has spread rapidly in Africa. Historically, clade I mpox has only been reported in five central African countries but it has now spread to other countries within Central and East Africa, and sustained sexual transmission has emerged in the DRC. Two travel-related cases have also been reported outside of Africa — in Sweden and Thailand — both in August 2024.

The 2022 outbreak

The first human case of mpox was identified in the DRC in 1970, eventually becoming endemic to Central and West Africa. But a surge in cases occurred in Nigeria between 2017 and April 2022, during which time 558 suspected cases were reported and the virus was exported to several countries, including the United States, UK, Israel and Singapore, where the virus is not endemic. By August 2022, a total of 25,864 cases were reported across 80 countries.

The UK was one of the first non-endemic countries to report an mpox case as part of the 2022 outbreak on 6 May that year, having identified the virus in a person who had visited Nigeria and then returned to the UK. A total of 3,732 highly probable and confirmed cases were reported in the UK by 31 December 2022, with 3,553 of those cases being in England.

In January 2023, the UK’s Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens recommended that the clade II mpox virus no longer be classified as a ‘high consequence infectious disease’ (HCID) because it no longer met the criteria, while the clade I virus remains an HCID.

Following this, the outbreak in the UK ebbed, with just 286 cases of mpox reported by the UKHSA between January 2023 and July 2024, and no fatalities.

UK response

In a statement published on 16 September 2024, Susan Hopkins, chief medical advisor at UKHSA, said: “The risk to the general UK population of being exposed to mpox clade I is currently considered low.

“However, we are preparing for any cases that we might see in the UK and vaccination plays a vital part in our defences.

“Alongside vaccination, we have been working rapidly to ensure that clinicians are aware and able to recognise cases promptly, that rapid testing is available, and that protocols are developed for the safe clinical care of people who have the infection and the prevention of onward transmission,” she added.

The government also published guidance on 15 August 2024, which advised all providers of clinical care “to ensure that they have adequate stocks of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and relevant staff are trained in its use for the assessment and treatment of patients presenting with suspected clade I mpox infection”.

Providers were also asked to “to ensure there is a clinical pathway for isolation and management of suspected clade I mpox cases within their setting”.

The guidance adds that this pathway “should include isolation of the patient, liaison with local infection prevention and control teams, and arrangements for discussion of the case with local infectious disease, microbiology or virology”.

“All pharmacy staff should familiarise themselves with the UKHSA alert issued on 15 August 2024 and any subsequent updates, and carefully consider how this guidance may affect their teams and the care they provide,” says Claire Anderson, president of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

“The situation is evolving and pharmacy teams must stay informed and prepared,” she adds.

Vaccination programme

In its latest statement, the UKHSA announced that the vaccine will be offered to those eligible in stages as it becomes available over time and based on clinical need (see Box 2).

Box 2: People who should be offered mpox vaccination

- Gay or bisexual men, or men who have sex with other men, and those who have multiple partners, participate in group sex or attend sex-on-premises venues (staff at these venues are also eligible);

- Certain healthcare workers in agreed infectious diseases inpatient units and sexual health services;

- Certain specialist healthcare and humanitarian workers who go to affected countries to work within mpox response or sites with active outbreaks following a risk assessment;

- People who have been in close contact with someone who has mpox — ideally, they should have 1 dose of the vaccine within 4 days of contact, but it can be given up to 14 days after.

An updated vaccination schedule was published in the Green Book alongside a briefing paper on technical elements of UK’s response for clade 1.

In July 2023, the NHS mpox outbreak vaccination programme was concluded; however, vaccination sites remain available in London and Greater Manchester, for those who are most likely to be exposed to the virus (see Box 2).

Healthcare professionals in the UK assessing rashes routinely should ask about travel history as part of the consultation

Nathan Burley, president of the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists

“There is currently no blanket vaccination advice for travelling to the DRC,” says Nathan Burley, advanced public and sexual health services pharmacist and president of the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists.

“However, sexually active gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men along with trans people and those presenting with additional risk of mpox acquisition, such as workers at sex-on-premises venues and laboratory workers handling orthopoxviruses, should get vaccinated at the appropriate place for them.”

During the initial outbreak in 2022, the UKHSA reported that 96.8% of mpox cases in England were reported in gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men.

“Healthcare professionals in the UK assessing rashes routinely should ask about travel history as part of the consultation,” adds Burley.

Vaccine efficacy

At present, there are two third-generation vaccines licensed for mpox globally. The Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine, available as Imvanex (Bavarian Nordic) in the UK and Europe, and LC16m8 (or LC16 “KMB”) vaccine, which is not licensed in the UK.

Imvanex, marketed as Jynneos in United States and Imvamun in Canada, is administered subcutaneously in two doses, 28 days apart, in those who are pre-exposed (see Box 2).

On 27 August 2024, the UKHSA told The Pharmaceutical Journal that the currently available vaccine should provide approximately 70% to 85% protection after the first dose in those not already exposed to mpox (based on evidence from the 2022 outbreak), but is much less effective in those already exposed, offering approximately 20% protection.

The UKHSA said the MVA vaccine was expected to work for both clades of mpox, but that it would conduct further assessments when an isolate is received.

Targeted response

Kevin Bardosh, director and head of research at Collateral Global, a UK charity for pandemic mitigation research, believes the mpox virus is unlikely to have a significant impact in the UK. “The fact of the matter is that this is something that’s endemic for decades in Sub-Saharan Africa, it typically proliferates in areas with malnutrition, food insecurity, war, conflict, and there’s very particular social circumstances and also poor health care systems.

“So, like any sort of sexually transmitted disease (STD), the likelihood of this really taking off as being a health problem in the UK is very low,” he adds.

“It doesn’t mean that there’s not going to be any cases. It just means that at a population level, this isn’t something that should concern the average person.”

Bardosh explains that, unlike other airborne diseases, such as COVID-19 or influenza, transmission of mpox is more difficult. He believes the focus for disease prevention should be in higher risk populations (see Box 2), as part of the routine STD programme.

Vaccines remain our first line of defence against future outbreaks

Richard Angell, chief executive at the Terrence Higgins Trust

Richard Angell, chief executive at the Terrence Higgins Trust, echoes this message: “We have been clear that we must learn the lessons from the last mpox outbreak in the UK.

“If a case of this new mpox clade is detected here, that means clear, non-stigmatising messaging, appropriate funding for the health system to respond and financial support for people to isolate if they need to.

“Vaccines remain our first line of defence against future outbreaks,” he says.

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Be helpful to have regular updates, has situation not moved on since 17th September (last update), now mid-November...