MAG

In 2014, a report published by UK researcher Roger Kline revealed a lack of ethnic diversity across all employees at London NHS trusts.

The report, ‘The snowy white peaks of the NHS’, showed that the proportion of board members from ethnic minorities in London’s NHS trusts was 8%, while overall, 41% of staff were from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds.

Kline’s conclusion was that it was time to urgently address the widespread and systemic discrimination that black and minority ethnic staff within the NHS face.

In the eight years since this report was published, there has been some progress on the representation of staff from ethnic minorities at senior levels of the NHS.

In 2015, the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) was introduced in England, which contractually obliged all NHS organisations to report the representation of staff from ethnic minorities at all levels publicly each year. The 2020 WRES report found that the total number of BAME staff at the ‘very senior manager’ pay band in England had increased by 42%, from 108 in 2017 to 153 in 2020.

NHS Workforce Statistics for England, published in January 2021, showed that at band 5 — the lowest level for graduates — 71.1% of staff were white. The proportion of staff who are white increases at each band up to the most senior level, ‘very senior manager’, at which 92.6% of staff were white and 7.4% were other than white.

In an attempt to shine a light on how these data apply to pharmacy roles in the NHS, The Pharmaceutical Journal submitted 209 requests under the Freedom of Information Act to NHS trusts and health boards in England, Wales and Scotland. We received 87 responses with comparable data.

Diversity in pharmacist posts

Overall, pharmacy is a diverse profession. According to the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC), pharmacists from ethnic minorities comprised 47% of registered pharmacists in 2019, with 43% from white backgrounds and 10% unknown or undisclosed.

However, data exclusively obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal from NHS trusts and health boards across Great Britain suggest that pharmacist management posts in the NHS may not be as diverse as would be expected.

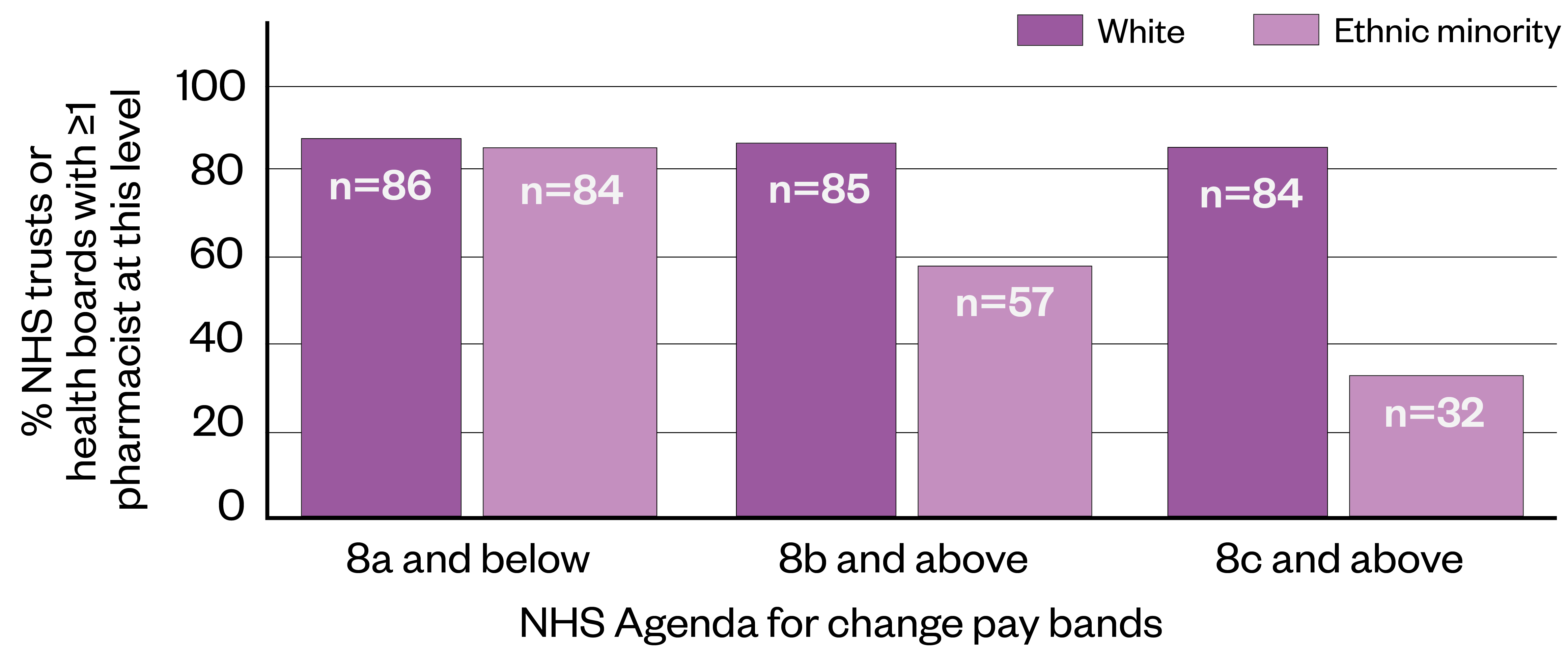

Of the 87 NHS trusts and health boards that provided the latest available data (either for 2021 or 2020), more than a third (34.5%) said they did not employ any pharmacists from ethnic minority backgrounds at band 8b or above; this compares with just two trusts (2.3%) whose data showed they had no white pharmacist staff at this level (see Figure).

Data from 87 NHS trusts in England, Scotland and Wales, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act

Newly qualified pharmacists usually begin their career at band 6, moving to band 7 once they have gained a few years’ experience in the role. Bands 8a–8d cover more senior roles, such as advanced and consultant pharmacists, as well as management of pharmaceutical services. Chief pharmacist roles are typically at band 9.

At band 8c and above, the effect was even more pronounced — 63.2% of the 87 NHS trusts and boards reported no pharmacist staff from an ethnic minority at this level. This compares with just 3.4% who reported no white pharmacists at this level.

There have been signs of a lack of diversity in the upper echelons of the sector for many years — The Pharmaceutical Journal’s annual salary and job satisfaction survey has shown a statistically significant ethnicity pay gap in favour of white pharmacists for the past four years.

The update in 2021 shows the median pay gap across all sectors was 7.3%, amounting to an annual cash difference of £3,569 for ethnic minority pharmacists (based on a 37.5-hour week).

Elsy Gomez Campos, president of the UK Black Pharmacist Association and the Pharmacists’ Defence Association BAME Network, said she was not surprised by The Pharmaceutical Journal’s findings from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests.

There is a widespread biased recruitment process embedded in our profession that we must stop allowing

Elsy Gomez Campos, president of the UK Black Pharmacist Association and the Pharmacists’ Defence Association BAME Network

“I believe they may be worse if we break it down into different ethnicities,” she said.

“[The profession needs to] take seriously how we are recruiting into senior leadership roles. In my experience, there is a widespread biased recruitment process embedded in our profession that we most stop allowing. This practice is denying career opportunities to the BAME pharmacy workforce.”

Aside from the simple justice of ensuring everyone has equal access to career progression, diverse staff representing the general population results in better care for patients.

A Health Education England (HEE) literature review of diverse leadership and patient care, undertaken and published in 2020, found evidence that diverse healthcare teams are associated with improved patient satisfaction with their care and better morale.

Barriers for ethnic minority staff

However, as the 2020 WRES report shows, this lack of progression is not purely a pharmacy problem. In its foreword, Prerana Issar, chief people officer at the NHS, wrote: “BAME staff members are less well represented at senior levels, have measurably worse day-to-day experiences of life in NHS organisations and have more obstacles to progressing in their careers.

“Much of [these inequalities are] experienced by BAME staff as subtle processes and behaviours that are often undetected by others,” she added.

The report also noted that in 83% of NHS trusts, a greater proportion of staff from ethnic minorities had experienced harassment or bullying from co-workers, compared with white colleagues.

It demonstrated that staff from ethnic minorities in acute settings were 20% more likely to enter formal disciplinary processes, compared with white staff.

This trend is reflected in the pharmacy sector: in 2020, as part of a consultation on how it will manage future fitness-to-practise concerns about pharmacy professionals, the GPhC set out to increase its “understanding of why a disproportionately high number of [fitness-to-practise] concerns are raised about BAME professionals”, with the aim of dealing “with any bias that we discover”.

Other healthcare professions have reported similar barriers to career advancement. For instance, a 2018 survey by the Royal College of Physicians of London revealed the results of a survey of 400 doctors in their first year after completing their training. According to the survey findings, when applying for their first job, 29% of white doctors were offered a post after being shortlisted, compared with 12% from ethnic minority groups.

Driving progress

Change may be coming, albeit slowly. In May 2020, the NHS established the NHS Race and Health Observatory, an independent body aiming to identify and address ethnic inequalities in health and care.

It says that “racial inequalities are ingrained in the institutions that constitute the NHS” and that it will be commissioning a review into current NHS systems, with the ultimate hope being to “identify and eradicate the causes of racial inequality” for both service users and workforce.

This review was published on 14 February 2022 and highlighted studies that were “largely qualitative and conducted mainly with women [which] showed how racism played out in the workplace to hamper ethnic minority staff’s career progression and professional development”.

The review also said there was “evidence for an ethnic pay gap in most staff sectors in the NHS and which was evident for Black, Asian, mixed and other groups, but less so for Chinese groups”.

Then, in March 2021, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), alongside the Association of Pharmacy Technicians UK (APTUK) and NHS England, published a ‘Joint national plan for inclusive pharmacy practice’ in England, which stated that pharmacy leaders at all levels should ensure that “the voices of colleagues of BAME origin are heard, valued, included as equal and considered when decisions are being taken”.

The document also said that pharmacy professional leaders must improve their understanding of how diverse teams benefit organisations, including “better potential to deliver more culturally competent and aware healthcare”.

How should these principles of inclusion look in practice? Several pharmacy leaders said the findings from the FOI requests raised fundamental questions about the barriers that pharmacists from ethnic minorities face in progressing their careers.

The solution comes from understanding and acting on the reasons why BAME candidates are not selected or do not apply for these roles

Paul Day, director of the PDA Union

Paul Day, director of the PDA Union, said that while the revealed lack of diversity at senior NHS levels was indicative of wider society, “pharmacy has a responsibility to address those causes of this issue that are within the reach of the profession”.

“[Part of the solution] comes from understanding and acting on the reasons why either BAME candidates are not selected or do not apply for these roles.”

Day suggested that employers should look at their recruitment practice, including providing equality training to those managing vacancy processes; reviewing adverts and job descriptions to ensure no structural discrimination; ensuring diversity of interview panels; and reviewing the interview process to ensure no unconscious bias.

Given that The Pharmaceutical Journal’s FOI requests focused on senior roles, Day also said it was important to ask questions about the inclusivity and opportunity for “pharmacists to access education and training and to have the chance to widen and develop management competency”.

Bigger than pharmacy

Roisin O’Hare, president of the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists (GHP), said it was “very disappointed, but sadly not surprised” by The Pharmaceutical Journal’s findings.

“[The GHP] encourages all of our members to be inclusive in all of their practice and have developed resources to support members to achieve this, alongside their mandatory training in equality and diversity, as well as unconscious bias training,” she said.

“The increased value and benefit of a diverse team in all settings has been widely published, not least in relation to innovative practices stemming from a greater breadth of experiences.”

O’Hare also noted that it is “important to establish how many colleagues from ethnic minority backgrounds have applied for senior positions in the first place”.

“Support and encouragement from those in senior and leadership positions can go a long way in encouraging and building confidence in the first instance when it comes to applying for these roles.”

Amandeep Doll, head of professional belonging at the RPS, said the FOI data confirmed what she had already heard from colleagues, but she believes that this was more than just about recruitment processes.

“It’s vital to encourage employees to progress so that there is representation at senior level as diversity ensures all perspectives are input to achieve the goal of inclusive pharmacy practice.

“A rigorous review of recruitment practices — combined with active encouragement and mentoring of senior ethnic minority pharmacists to become leaders — are just two ways in which the situation can improve, along with data collection to monitor and evaluate the success of measures undertaken.

“However, this isn’t just about fairer hiring polices — discrimination needs to be taken seriously so people can thrive and also means looking at systemic and institutional racism that exists in organisations.”

Box 1: Our methodology

Freedom of Information (FOI) requests were sent to 188 NHS trusts and local health boards in England between September and November 2021, and in Wales and Scotland in May 2021.

The focus of the request — in which we asked for the latest available data — was to find out the number of pharmacists who identify as white, black or ethnic minority and ‘unknown’, in each of the Agenda for Change pay bands, from band 6 to ‘very senior manager’, which sits above band 9.

A total of 87 trusts and health boards were included in the analysis. We excluded data from trusts or boards who were unable to provide precise or comparable data of the number or ethnicity of their pharmacist staff, often owing to the risk of members of staff potentially being identifiable.

Any trust or health board that reported no pharmacist staff employed at bands 8b or above was excluded from the analysis.

Unfortunately, owing to the risk of members of staff being identifiable, we were not able to obtain data for separate ethnic minority groups.

Box 2: Responses

A spokesperson for the Scottish government said it was working with NHS Education for Scotland and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society to encourage more people to consider careers in pharmacy, including underrepresented sections of the population.

“Fostering an inclusive culture that reflects the diversity of Scotland in the NHS is the cornerstone to improving everyone’s experience within NHS Scotland,” they said.

“Direct engagement between senior leaders in health and social care and staff needs is key to ensuring a change in culture. We are working to ensure that health board chairs have a meaningful anti-racist and wider equality objective that will make senior leaders accountable for meaningful action on diversity and inclusion.”

When approached for comment, NHS England referred to the 2020 NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard report, noting that there were now more ethnic minority staff at ‘very senior manager’ level overall in the health service.

The Welsh government was approached for comment but had not responded at the time of publication.