Garo / Phanie / Science Photo Library

Desperate to help their children with treatment-resistant epilepsy, parents have rallied around an unlikely plant — Cannabis sativa— in recent years. Although better known for its highs and haze, the medicinal properties of cannabis have been touted since antiquity.

Now, as more US states legalise cannabis, dispensaries prepare and sell extracts of the whole plant in oil, typically strains high in cannabidiol (CBD) and low in Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive ingredient responsible for the high that cannabis causes. Internet forums offer anecdotes of children getting relief from seizures, and parents share advice on the best strains and dosages for treatment. In the UK, people can choose from a range of products containing CBD, such as chewing gum, tea and skin cream.

Despite the easy availability and appeal of this natural medicine, these products are unregulated and untested, which puts doctors and patients in a difficult position.

“It’s hard to tell people whose child is seizing many times a day, and they’ve tried every available medication, that they shouldn’t try some oil they got off the internet,” says Daniel Friedman, a neurologist at New York University. “They’re looking for something, for hope, and there’s somebody giving them hope.”

It’s hard to tell people whose child is seizing many times a day, and they’ve tried every available medication, that they shouldn’t try some oil they got off the internet

But it is easy to be fooled. Different oils vary in their mixture of active ingredients, and many do not even contain what they claim to, according to test results released by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2016. Wishful thinking may also drive many of the reported improvements: for example, a study in the state of Colorado, where cannabis is legal, found that parents who had moved to the state expressly to obtain cannabis products for their children reported twice the decrease in seizure frequency than those who lived in Colorado already[1]

.

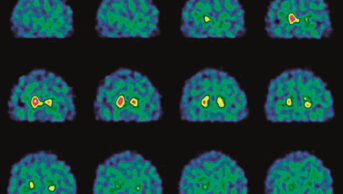

Figure 1: Marijuana’s increasing popularity for childhood epilepsy

Source: Medical Marijuana Registry, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

There were 40 patients under 18 years old on Colorado’s Medical Marijuana Registry at the beginning of 2013, but this increased dramatically after a special documentary entitled “Weed” aired on CNN in August 2013. The documentary, by neurosurgeon and chief medical correspondent for CNN Sanjay Gupta, featured the case of Charlotte Figi, a five-year-old girl with Dravet syndrome, who was having 300 seizures per week despite being on seven epilepsy medicines. After starting medical marijuana, her seizure frequency reduced to just two to three per month.

“I think that speaks a lot to bias, to how powerful it is in these families who have typically tried 10 or 12 medications before they get here,” says Kristen Park, a neurologist specialising in childhood epilepsies at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Park was not involved in the study, but she fields questions about cannabis everyday. “I think that study validated the need to be cautious,” she adds.

Source: Courtesy of Kristen Park

Kristen Park, a neurologist specialising in childhood epilepsies at Children’s Hospital Colorado, says families who have already tried numerous medicines may overestimate the benefits of cannabis products

Science may finally be catching up with the enthusiasm for cannabis. Several pharmaceutical companies are now conducting clinical trials of CBD-based drugs, with one poised to be approved by the FDA as early as 2017 for two paediatric epilepsy syndromes. Although these trials will provide some welcome guidance on safety, dosage and efficacy, concerns remain about side effects such as sedation, interactions with other drugs, and potential disturbances of brain development. Whether these CBD medicines, mostly tested in children with rare epilepsies, will translate to more common epilepsies in adults also remains to be seen.

Even as CBD’s effectiveness may soon be established in rigorous clinical trials, experts see it as one of many new additions to the arsenal of epilepsy medicines, rather than a panacea.

“The little evidence that is starting to make a dent in the hype about cannabis being a miracle treatment is going to help people make informed decisions about what they feel is appropriate risk for their child,” says Park.

The little evidence that is starting to make a dent in the hype about cannabis being a miracle treatment is going to help people make informed decisions about what they feel is appropriate risk for their child

Calming cannabinoids

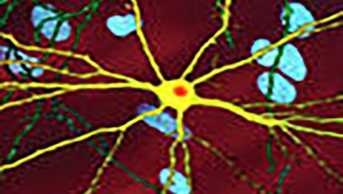

People with epilepsy are prone to seizures, which can range from brief lapses in attention to disabling episodes of involuntary movements and unconsciousness. Seizures stem from overactive neurons in the brain that run out of control. This state can arise for different reasons, leading to different seizure types and different forms of epilepsy.

Current medicines keep seizures in check for a majority of people with epilepsy — up to 65 million worldwide. But around 30% of people do not get control over their seizures. Rare epilepsies that arise in childhood, such as Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, are particularly intractable, with children still experiencing 50–75 seizures a day, despite taking multiple medicines. Even new medicines developed in the past decade still do not thwart seizures in children with these conditions, and they could face greater disability if uncontrolled seizures derail their brain development.

Although cannabis was used as treatment for epilepsy in Victorian times and even earlier, the practice declined as other medicines were discovered and the plant was deemed illegal. Interest revived in the 1990s with the discovery of an endogenous cannabinoid system in the brain, which consists of two receptors, cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and CB2, and two endogenous ligands, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide. The most abundant components of cannabis are cannabinoids, a family of compounds that share chemical structures unique to the plant. Of these, three cannabinoids bind to CB receptors, including THC and CBD.

Years of preclinical work in rodent models of seizure uncovered anticonvulsant powers of CBD and, to a lesser extent, cannabidivarin (CBDv). Although how they work is still being investigated, it may not involve the CB receptors themselves, says Ben Whalley, a pharmacologist at the University of Reading. Instead he suspects other molecular targets, many of which relate to the modulation of calcium: VDAC1, an ion channel present on mitochondrial membranes; CAV3.3, a voltage-activated calcium channel; GPR55, an orphan G-protein receptor that modulates calcium in the presynaptic terminal to regulate excitatory neurotransmitter release; a serotonin receptor, 5HT1R; glycine receptors; and adenosine, a ligand that acts through adenosine 1 receptors[2]

.

Source: Courtesy of Ben Whalley

Ben Whalley, a pharmacologist at the University of Reading, says that, so far, no evidence of synergy has been found for combinations of cannabidiol and cannabidivarin in animal models of seizure

Once the true targets are identified, they could point the way to entirely new classes of drugs.

“There’s nothing to suggest that CBD is the best thing operating at these targets,” says Whalley. “So finding out what the targets are could offer an insight into what makes these hard to treat epilepsies so hard to treat.”

There’s nothing to suggest that CBD is the best thing operating at these targets, so finding out what the targets are could offer an insight into what makes these hard to treat epilepsies so hard to treat

Some proponents of whole cannabis extracts argue that studying its components in isolation may fail to capture their full effects, but so far there isn’t any evidence for synergy.

“I get quite frustrated with the concept that because something appears as a crude mixture in a plant, it must be kept as a crude mixture from a plant, otherwise it will stop working,” says Whalley, noting that researchers can and do find evidence for synergy, but that so far nothing has been found for combinations of CBD and CBDv in animal models of seizure.

Even in isolation, however, CBD’s effects in humans may be, in part, indirect. CBD changes the metabolism of other epilepsy medications such as clobazam, causing their levels to rise. This compels doctors to check blood levels of medications once CBD treatment has begun, says Edward Novotny, a neurologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington, a state that has legalised cannabis.

Source: Courtesy of Edward Novotny

Edward Novotny, a neurologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington, says cannabidiol changes the metabolism of other epilepsy medicines, causing their levels to rise

Novotny describes the case of a three-year-old patient who, when CBD was added to the treatment regimen, experienced a doubling of concentration of another anticonvulsant. “The child fell asleep, and basically was asleep almost constantly for hours and days at a time,” he says.

Orphan trials

The widespread availability of cannabis-derived products calls for rigorous clinical trials. But in the United States, research is slowed because CBD is categorised as a schedule 1 drug, which means it belongs to the most restricted substances deemed of no medicinal value. Until recently, studies in humans have been too small to draw firm conclusions and, considered together, they did not recommend CBD for epilepsy[3],

[4]

.

There is a worry, in an open label study where everyone knows what they’re getting, that something that’s subtle may be blown up by a hopeful parent

The tide is starting to turn, however. In 2016, an open label study found that adding CBD to treatment was safe and tolerable in people with Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and other types of epilepsy that had not responded adequately to conventional medicines[5]

. The CBD compound, called Epidiolex, has been developed by GW Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, which has already brought a THC-based drug called Sativex to market to treat spasticity. Epidiolex halved the frequency of motor seizures, as reported by parent questionnaire, in children and adults, but adverse effects, such as sleepiness, were also noted.

“There is a worry, in an open label study where everyone knows what they’re getting, that something that’s subtle may be blown up by a hopeful parent,” says Friedman, one of the study’s authors. “That’s why a randomised trial is necessary, that’s why they’re done.”

The intense public interest in cannabis means that developing a fully characterised, consistent medicine demonstrated to be safe and effective compared with placebo is more important than ever, says Stephen Schultz, vice president of investor relations at GW Pharmaceuticals. “Science is trying to provide physicians and patients with an option that provides these hallmarks that they typically expect from a pharmaceutical medicine,” he says. “None of those hallmarks are true of the dispensary-based artisanal oils on offer, and likely will not be.”

Placebo-controlled trials are under way, with promising —though unpublished — results reported in 2016. GW Pharmaceuticals reported positive results in press releases for Epidiolex over placebo in three phase III trials – one in Dravet syndrome and two in Lennox-Gastaut. In each trial, a 14-week course of Epidiolex added to current medicines decreased seizure frequency by at least twice as much as placebo. Most participants, however, also reported mild to moderate side effects, such as sleepiness or decrease in appetite.

The focus on rare, childhood epilepsies reflects the dire need for medicines, but is also a business decision: Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut syndromes have been designated as “orphan diseases” by the FDA because of their lack of treatments. Any drug approved for an orphan disease is granted market exclusivity for 7.5 years. This is an attractive option for Epidiolex, which is derived from plants containing high CBD levels — naturally-occurring compounds cannot be given a “composition of matter” patent.

GW Pharmaceuticals is now working on a new drug application for Epidiolex to submit to the FDA. It also has a phase II trial under way for another cannabinoid, cannabidivarin (CBDv), in adults with focal epilepsy, where seizures are localised to one side of the brain.

The positive results may well translate to adult forms of epilepsy, says Schultz. If Epidiolex is approved, the indication would be for seizures associated with Dravet or Lennox-Gastaut syndromes. Such seizure types are also found in other epilepsies, and so a doctor could make a decision on whether to try it for someone who has some of the same seizure types, if not the same condition.

But others are not convinced that what works in children will work in adults. As children mature, their brains undergo substantial changes as neurons form or prune back connections. This may explain why some medicines stop working for some children, or why some children outgrow certain seizure types or even epilepsy itself.

“Drug studies done in a child’s nervous system, which is dynamic, growing and changing, may not translate to adults, where the brain is mature and fixed,” says Novotny. “It’s really hard to extrapolate both ways.”

Drug studies done in a child’s nervous system, which is dynamic, growing and changing, may not translate to adults, where the brain is mature and fixed

Novotny also has concerns about potentially disruptive effects of CBD on brain development, citing links between cannabis and brain development[6]

and function[7]

. It is also unclear whether taking CBD on a long-term basis would have similar effects.

Topical treatment

Other companies earlier in their development of cannabinoids for epilepsy are taking different approaches. INSYS Therapeutics, based in Chandler, Arizona, has developed a synthetic form of CBD, which it says has manufacturing advantages over the plant-derived variety.

Source: Courtesy of INSYS Therapeutics

INSYS Therapeutics, based in Chandler, Arizona, has developed a synthetic form of cannabidiol, which it says has manufacturing advantages over the plant-derived variety

“With a plant-derived compound, there will be variation between plants, variation in watering and other conditions that must be maintained over years to allow for the same level of quality,” says Santosh Vetticaden, chief medical officer at INSYS. “A synthetic does not have these intrinsic challenges.”

INSYS’s CBD compound has been tested in an initial trial examining different dosages and safety for children with refractory paediatric epilepsy; a long-term safety trial is under way. The company is also conducting a trial for infantile spasms in children aged between 6 months and 3 years.

A topical preparation of CBD has also been developed by Zynerba, based in Devon, Pennsylvania, with the idea that it provides a more efficient way to get CBD into the bloodstream than oral medicines. The compound, ZYN002, may also avoid some of the sedating side effects of CBD: Zynerba’s research team has gathered evidence that suggests that CBD, when in the stomach, could be metabolised into THC, which may contribute to sedation.

Currently Zynerba is conducting a phase II trial of ZYN002 in adults with treatment-resistant epilepsy in Australia and New Zealand, where CBD is not a controlled substance. The company already has a patent on their formulation and, if clinical trials are successful, it anticipates approval in 2020.

In the meantime, as the clinical trials roll on, doctors struggle to tread the best course for their patients.

“I think our priority as clinicians is not to tell people that they shouldn’t try this if they’ve exhausted conventional therapies, but to educate them about what’s known and unknown and what are the safety risks,” says Friedman. “They can [then] make the best informed decision they can about treatments for their family members.”

References

[1] Press CA, Knupp KG & Chapman KE. Parental reporting of response to oral cannabis extracts for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2015;45:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.02.043

[2] Ibeas Bih C, Chen T, Nunn AV et al. Molecular targets of cannabidiol in neurological disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2015;12:699–730. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0377-3

[3] Gloss D & Vickrey B. Cannabinoids for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(3):CD009270. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009270.pub3

[4] Koppel BS1, Brust JC, Fife T et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2014;82:1556–1563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363

[5] Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D et al. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: an open-label interventional trial. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:270–278. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00379-8

[6] Lorenzetti V, Solowij N, Yücel M et al. The role of cannabinoids in neuroanatomic alterations in cannabis users. Biological Psychiatry 2016;79:e17-31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.11.013

[7] Broyd SJ, van Hell HH, Beale C et al. Acute and chronic effects of cannabinoids on human cognition—A systematic review. Biological Psychiatry 2016;79:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.002