Mclean/Shutterstock.com

“One in four consultations in primary care involve fatigue — it’s the most common reason why people go to see their GP,” says Julia Newton, a consultant physician with an interest in fatigue at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

At least 250,000 people in the UK live with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a long-term neurological disease with a wide range of symptoms, including debilitating pain, fatigue and crashes after activity known as post-exertional malaise. And self-reported data indicate that 50% of people with chronic conditions — such as rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, or multiple sclerosis (MS) — struggle with tiredness[1–3]. “Despite that, there’s very little research,” points out Newton.

Lack of funding has left fatigue science decades behind the scientific understanding of other chronic symptoms, such as pain.

In part, this is owing to the heterogeneity of how fatigue is experienced. On top of presenting across multiple conditions, it can be emotional, physical, cognitive or motivational in nature, and varies from person to person — even from day-to-day for the same patient (see Box). This diversity means conducting research can be a tricky and unattractive investment.

Box: What do we know about chronic fatigue?

“There isn’t [an accepted] scientific definition of fatigue — there isn’t a physiological, biochemical understanding of what the pathophysiology of fatigue is,” states Julia Newton, a consultant physician with an interest in fatigue at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. “It is a symptom that is described by patients, so it’s a word that can often be used to describe a whole range of different things.”

“There are quite a few things we need to understand about fatigue,” stresses Anna Kuppuswamy, principal research fellow in clinical and movement neurosciences at University College London. “We have acute fatigue and chronic fatigue, and they are completely different from each other — that’s never made clear.”

“Early fatigue is considered part of sickness behaviour; inflammation-induced reduction of performance and activity, and a feeling of tiredness which accompanies it. It’s supposed to be an effective mechanism to focus on recovery rather than just doing things.” Like pain, fatigue is a message to our body that something is wrong.

“But if you think about chronic fatigue, that’s where it starts to get very murky; it’s sort of a free for all, it could be anything.” In chronic fatigue, the switch to turn this message off is not flicked.

It is yet to be understood what this switch is, along with the mechanisms involved in the message system; a complex mixture of inflammatory mechanisms, metabolic and autonomic dysregulation, neuroendocrine pathways, and psychological disturbances, such as sleep disorders, have all been implicated as contributors to fatigue pathology[4].

Without a good endpoint, you’re never going to get the investment you might need to get a drug to market

Julia Newton, consultant physician with an interest in fatigue, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

“It’s made more complicated by the fact it’s really hard to measure fatigue — not impossible, but it is hard, it’s really subjective,” Newton explains. “In order to encourage the pharmaceutical industry to come and to develop their drugs, you need a good end point — that’s the problem at the minute. [Without it] you’re never going to get the investment you might need to get a drug to market.”

But this could be changing. With fatigue consistently ranked as the most frequent self-reported symptom associated with long COVID, the powerhouse of global COVID research — and the funding that comes with it — has the potential to dramatically remodel the landscape of fatigue science and therapy[5].

And it’s sorely needed. For patients currently living with fatigue, this landscape is pretty sparse.

Getting it wrong

There are currently no approved pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions for chronic fatigue, across any of the conditions it is present in. For ME/CFS, the 2021 revision of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE’s) guidance for managing the condition removed a previously recommended therapy — graded exercise therapy (GET), a programme of fixed, incremental increases in exercise — and downscaled the scope of another — cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) — because a re-evaluation of the evidence base for these therapies failed to show meaningful benefit.

GET and CBT were used as early interventions that aimed to improve ME/CFS symptoms by tackling ‘unhelpful beliefs’ patients were thought to hold about exercise and activity patterns; a model where psychology was considered a root cause of fatigue[6]. In acknowledgement of current understanding for a physiological basis for chronic fatigue, together with patient and expert experience, CBT recommendations are now limited to helping patients cope with symptoms — not as a possible ‘cure’ for fatigue behaviour[7]. Accumulating data for GET suggest that forced exercise targets actually make ME/CFS symptoms worse; in one survey, this was true for 38% of patients treated with GET compared with 6% who found it helpful[6,8].

We found GET produced, at best, a moderate effect in a small number of people, and that effect wasn’t long-lasting compared with no intervention

Peter Barry, non-expert chair of the ME/CFS NICE guideline committee

“There was a strong signal of risk of harms from GET,” Peter Barry, non-expert chair of the ME/CFS NICE guideline committee, says of the panel’s appraisal of the evidence base.

“We found GET produced, at best, a moderate effect in a small number of people, and that effect wasn’t long-lasting compared with no intervention, and the evidence around GET was of low or very low quality. The committee felt as a whole, that given [the] low quality of [evidence of] an, at best, moderate benefit, which wasn’t long-lasting, against a strong signal of harms, it shouldn’t be recommended.”

While these changes were mostly welcomed as a step in the right direction, it has effectively put ME/CFS care back at square one, with a distinct lack of therapeutic options.

“There’s nothing, there’s no treatments in the NICE guideline,” Newman agrees, adding: “You’re almost left with a blank piece of paper.”

So what can a patient with chronic fatigue expect from care now?

The three Ps

Both the updated NICE ME/CFS and long COVID guidance focus clinical support for fatigue on the concept of self-management — assisting the patient to build up a set of skills themselves to cope with their illness. In chronic fatigue this involves thinking carefully about energy use[7,9].

We’ll often use the analogy of a mobile phone battery and encourage people to think about how they are using their battery of energy

Rachel Rogers, a fatigue specialist occupational therapist at the long covid clinic based at Churchill Hospital, Oxford

“We talk about the three Ps approach — prioritising, planning, and pacing,” says Rachel Rogers, a fatigue specialist occupational therapist at the long COVID clinic based at Churchill Hospital, Oxford, and clinical lead for Oxfordshire’s ME/CFS service. Rogers describes the patient journey for someone presenting with long COVID fatigue.

“We’ll often use the analogy of a mobile phone battery and encourage people to think about how they are using their [battery of] energy,” she says. Patients are advised to prioritise where they are going to spend their energy and not waste any unnecessarily, and plan out how they might use the limited energy across the day and week.

“And then, with pacing, how they are going to break tasks down into smaller more manageable chunks and top up that energy battery with periods of rest throughout the day,” she adds.

Pacing helps eke out the patient’s energy or ‘battery life’ so it doesn’t drain completely. If that happens, “one of the patterns that people will fall into is this ‘boom and bust’”.

“They’ll have a good day, they’ll feel as if they’ve got a bit more energy, and they’ll race around trying to get everything done that they’ve not managed to do for a while, and end up crashing in a heap, spending two or three days recovering,” Rogers cautions. “So, it’s about trying to avoid too many of those dips and crashes and spread out their energy expenditure.”

Referred to as post-exertional malaise (PEM), crashes are notoriously difficult to predict and prevent, and it is even harder to do so when already struggling with fatigue.

“Not everyone even understands they are having a bout of PEM,” says Nicholas Sculthorpe, an exercise physiologist at the University of West Scotland. “And bouts of PEM can be delayed by three or four days from what actually triggered it, so you’ve got to try and track all of that for three or four days at least to get an idea of your triggers. And on top of all that, [what if] you’ve got brain fog[?]”

As part of a recent round of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funding for long COVID[10], Sculthorpe is trialling a modern solution for PEM: a Fitbit, linked to a purpose-built app that alerts wearers if they are close to exceeding energy thresholds. “We could say, you’ve been very active this morning, maybe this afternoon you could take a rest,” says Sculthorpe, outlining the concept. As a proxy measure of energy use, the team are tracking the time spent at an elevated heart rate. “We’ll send a message that will say, you’ve used 15 minutes of your 30-minute threshold already today.”

This ‘Fitbit-in-reverse’ hopes to offer an easy way for patients to understand their energy variables; to better gauge the amount of energy different activities require to help plan better in the future, or retrospectively analyse their data to pinpoint triggers of PEM. “The whole point is to give people an external brain for all of that.”

Active treatment

Sculthorpe’s study, which received £317,416 in funding, is a prime example of how chronic fatigue research is starting to be taken more seriously.

But research efforts are not stopping at supportive tools; another study, receiving £640,180 of NIHR funding, is the Percutaneous Auricular Nerve Stimulation for Treating Post-COVID Fatigue (PAuSing-Post-COVID Fatigue) study, which applies electrostimulation to the auricular vagus nerve, in an intervention known as neuromodulation[10]. “It’s what is increasingly referred to as an ‘electroceutical’,” says lead investigator Mark Baker, senior clinical lecturer at Newcastle University.

In a 16-week cross-over study in 96 subjects with post-COVID-19 fatigue, the electrical stimulation is applied for an hour, three times daily, by a transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) machine, a small device already marketed for pain relief in conditions such as endometriosis or sports injuries. Building on a small study of 15 subjects with Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease, that showed improved fatigue scores after 28 days of twice-daily vagus nerve electrostimulation, Baker says the team is “hoping to see improvements after eight weeks of continued treatment”[11,12]. Pathological mechanisms for chronic fatigue are not fully understood, but the autonomic nervous system — the vagus nerve and its crosstalk to the immune system — is thought to play a role in fatigue modulation[4].

The thinking is that the virus might be potentially hijacking the mitochondria and affecting their ability to process fuel and energy for the cell

Betty Raman, clinical transition intermediate fellow at the British Heart Foundation Oxford Centre of Research Excellence and lead investigator of the AXA1125 trial

Investment in drug-based therapies for chronic fatigue is also trickling through; an early front-runner to reach phase IIb testing in the UK is clinical-stage biotechnology sponsor Axcella’s candidate AXA1125[13,14]. An oral powder mix of six amino acids, AXA1125 has previously boosted mitochondrial function in clinical trials with subjects with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), where mitochondrial metabolism in the liver is faulty[13,15]. Mitochondrial problems are similarly implicated in ME/CFS, and Betty Raman, clinical transition intermediate fellow at the British Heart Foundation Oxford Centre of Research Excellence and lead investigator of the AXA1125 trial, explains that evidence points to this in long COVID fatigue too[16,17].

“Cardiopulmonary testing has identified that there are abnormalities in the body’s ability to use oxygen efficiently [in long COVID fatigue]. Other tests have detected a reduced activity of the mitochondria in peripheral blood cells. So, it’s believed that one basis for [long COVID fatigue] could be mitochondrial dysfunction.

“The thinking is that the virus might be potentially hijacking the mitochondria and affecting their ability to process fuel and energy for the cell.”

Long COVID patients with fatigue in the UK are eligible for enrolment in this trial; but studies of other potential therapies are ongoing internationally too. US-based biotech company Resolve Therapeutics is testing its autoimmune disease candidate RSLV-132 in a phase II, 10-week study of 70 subjects with long COVID[18][19]. RSLV-132, a ribonuclease that breaks down strands of pro-inflammatory RNA before they can be translated into inflammatory proteins, has already shown benefit in improving fatigue in Sjögren’s syndrome. “Based on our previous positive phase II clinical trial with RSLV-132 in autoimmune fatigue, we are hopeful that removing circulating RNA in long COVID patients will have a similar improvement in their fatigue and brain fog,” says James Posada, chief executive officer of Resolve Therapeutics[20].

Similarly, Ageless Rx, a US-based telehealth ecommerce start-up, is testing two candidates in a 12-week pilot study of 60 subjects with fatigue following COVID-19 infection[21,22]. The first intervention, oral low-dose naltrexone (4.5mg), picks up from several previous studies indicating low-dose naltrexone improved fibromyalgia symptoms, including fatigue[23,24]. The second intervention, topical patches of the metabolic enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), is another targeted at cell energy processing[25].

In June 2022, Terra Biological, also based in the United States, reported positive results from a small proof-of-concept trial in ME/CFS and long COVID fatigue patients with its nutritional supplement oxoalocetate[26]. Another intervention taking aim at metabolic processes, the improvements seen warrant further investigation in ME/CFS and long COVID fatigue, the company says.

Investment in chronic fatigue is gathering momentum. But with most of this research in long COVID patients, what does this mean for those for whom fatigue has been a reality for decades?

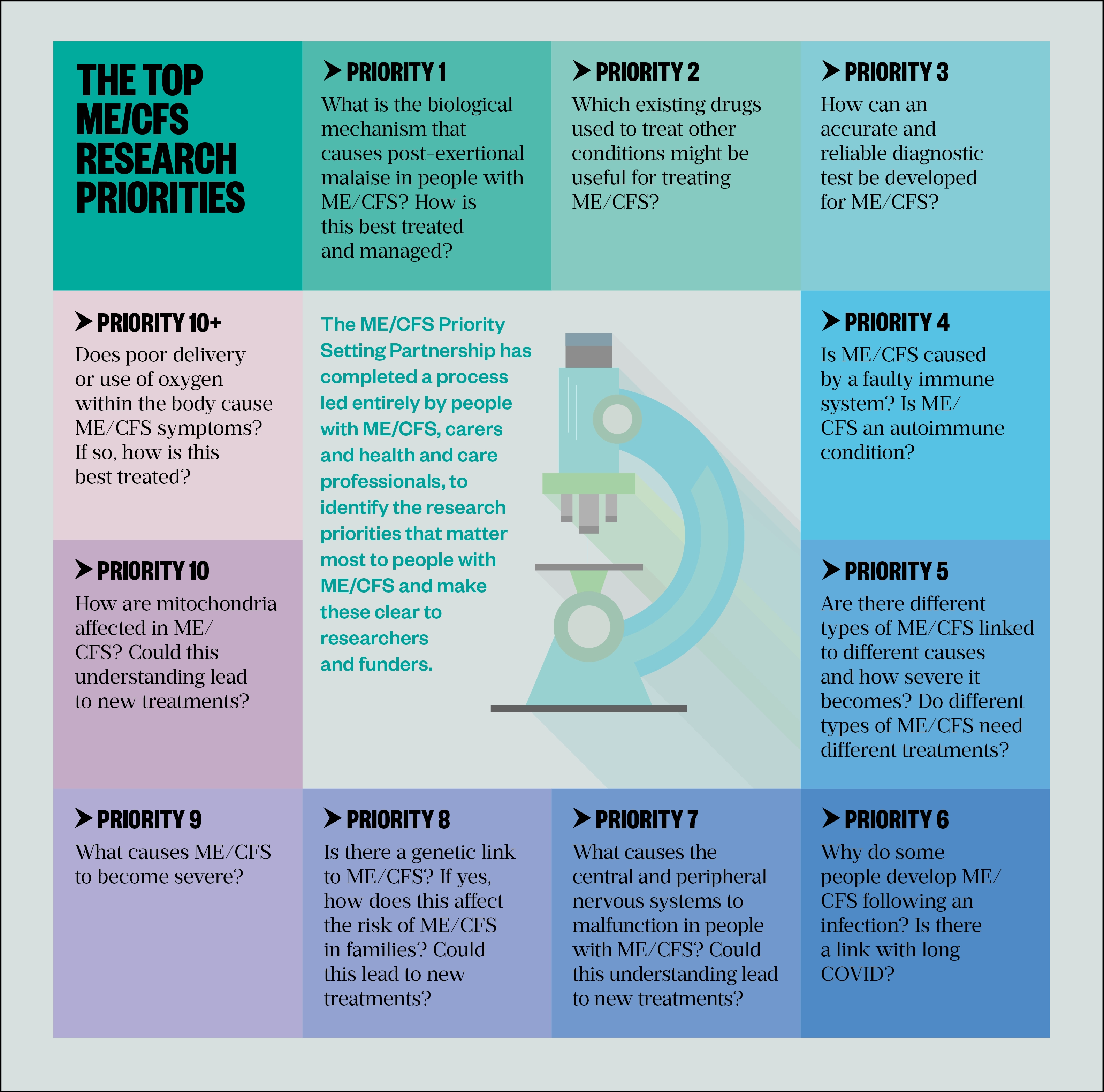

The answer might not be too far away. In May 2022, the then UK health secretary Sajid Javid announced that as part of a package of government support for ME/CFS, he is co-chairing a roundtable focusing on research priorities that include exploring possible links between ME/CFS and long COVID, and whether drugs explored for fatigue in other conditions, such as low-dose naltrexone, could work in ME/CFS, as well as getting to the bottom of the biological mechanisms behind ME/CFS and symptoms such as PEM (see Figure)[27,28].

“I am excited and optimistic that this represents a new horizon for those with this terrible illness that will provide opportunities for new treatments and a greater understanding of the impact ME/CFS has on people’s lives,” says Newton, who is a participant at the roundtable.

Chronic fatigue research has an uphill journey ahead of it, but it seems to be finally moving in the right direction.

- This feature was amended on 19 July 2022 to clarify the difference between myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), which is a long-term neurological disease with a wide range of symptoms, including fatigue, and chronic fatigue, which is a symptom of a number of different conditions

- 1What is ME? ME Research UK. https://www.meresearch.org.uk/what-is-me/#:~:text=ME%2FCFS%20affects%20an%20estimated%20250%2C000%20people%20in%20the,sclerosis%2C%20congestive%20heart%20failure%20and%20other%20chronic%20conditions (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 2McAteer A, Elliott AM, Hannaford PC. Ascertaining the size of the symptom iceberg in a UK-wide community-based survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e1–11. doi:10.3399/bjgp11x548910

- 3Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Tiredness/fatigue in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/tiredness-fatigue-in-adults/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 4Davies K, Dures E, Ng W-F. Fatigue in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: current knowledge and areas for future research. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17:651–64. doi:10.1038/s41584-021-00692-1

- 5Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 2 June 2022. Office for National Statistics. 2022.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1june2022 (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 6Managing your symptoms. Action for ME. https://www.actionforme.org.uk/get-information/managing-your-symptoms/graded-exercise-therapy/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 7Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/resources/myalgic-encephalomyelitis-or-encephalopathychronic-fatigue-syndrome-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66143718094021 (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 8Five year Big Survey. Action for ME . https://www.actionforme.org.uk/research-and-campaigns/five-year-big-survey/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 9National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Royal College of General Practitioners. Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-the-longterm-effects-of-covid19-pdf-51035515742 (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 10Department of Health and Social Care. New research into treatment and diagnosis of long COVID. Gov.uk. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-research-into-treatment-and-diagnosis-of-long-covid (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 11Davies K, Ng W-F. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.702505

- 12Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG. Measurement of fatigue and discomfort in primary Sjögren’s syndrome using a new questionnaire tool. Rheumatology. 2004;43:758–64. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh170

- 13Axcella Health. AXA1125 Now in Phase 2a and 2b Development: AXA1125 in Long COVID. Axcella . https://axcellatx.com/pipeline/axa1125 (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 14Efficacy, Safety, Tolerability of AXA1125 in Fatigue After COVID-19 Infection. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2022.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05152849 (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 15Chakravarthy MV, Neuschwander‐Tetri BA. The metabolic basis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Endocrinol Diab Metab. 2020;3. doi:10.1002/edm2.112

- 16Stephens C. MEA Summary Review: The role of Mitochondria in ME/CFS. The ME Association. 2019.https://meassociation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/MEA-Summary-Review-The-Role-of-Mitochondria-in-MECFS-12.07.19.pdf#:~:text=Mitochondria%20are%20the%20part%20of%20the%20cell%20responsible,and%20have%20been%20primarily%20linked%20to%20mitochondrial%20dysfunction (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 17Roberts E. Mitochondria and CFS. ME Research UK. 2021.https://www.meresearch.org.uk/mitochondria-and-cfs (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 18Clinical trials. Resolve Therapeutics. 2021.https://resolvetherapeutics.com/product-candidates/clinical-trials/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 19Resolve Therapeutics. A Study of RSLV-132 in Subjects With Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome (RSLV-132). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2021.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03247686 (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 20Resolve Therapeutics Receives FDA Approval to Initiate Phase 2 Clinical Trial of RSLV-132 in Long Covid Patients. Resolve Therapeutics. 2021.https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.206/dxk.7e7.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Long-Covid-PR-22Jun2021.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 21AgelessRx Launches Pilot Post-COVID Clinical Trial. Ageless Rx . 2021.https://agelessrx.com/agelessrx-launches-pilot-post-covid-clinical-trial/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 22Post COVID clinical trial. Ageless Rx . https://agelessrx.com/postcovid/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 23Younger J, Noor N, McCue R, et al. Low-dose naltrexone for the treatment of fibromyalgia: Findings of a small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, counterbalanced, crossover trial assessing daily pain levels. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2013;65:529–38. doi:10.1002/art.37734

- 24Younger J, Mackey S. Fibromyalgia Symptoms Are Reduced by Low-Dose Naltrexone: A Pilot Study. Pain Med. 2009;10:663–72. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00613.x

- 25AgelessRx Research. A discussion with Dr. Sajad Zalzala on the currently enrolling Chronic COVID study (long haulers). YouTube. 2021.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7NehyJtJsI (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 26Cash A, Kaufman DL. Oxaloacetate Treatment For Mental And Physical Fatigue In Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long-COVID fatigue patients: a non-randomized controlled clinical trial. J Transl Med. 2022;20. doi:10.1186/s12967-022-03488-3

- 27Sajid Javid – 2022 Statement on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. UKPOL political speech archive . 2022.https://www.ukpol.co.uk/sajid-javid-2022-statement-on-myalgic-encephalomyelitis-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

- 28The top 10+ ME/CFS research priorities. The ME/CFS Priority setting Partnership. https://psp-me.co.uk/ (accessed 20 Jun 2022).

6 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chronic fatigue is something completely different to ME/CFS. This is written with the terms confused. The complex multisystem disease, ME/CFS, see NICE Guideline ME/CFS 2021, is marked out by the symptom Post Exertional Symptom Exacerbation which includes fatigue (understatement to the point of being absurd) as well as other symptoms. It is not defined by fatigue. Chronic fatigue on the other hand just means fatigue that has become chronic, it is a single symptom that can arises from any number of other conditions such as multiple sclerosis, arthritis or even depression. It seriously doesnt help when articles confuse the two, and causes even more harm when research cohorts confuse the two - the results end up useless and potentially even harmful. Please correct the title so it is clear which of these two things the article is about, is it about the disease ME/CFS as in the NICE Guideline, or is it about the symptom of something else,, chronic fatigue? Thanks

Thanks for your helpful comments on our feature. The feature aims to explore what is known about fatigue in general, and the specific impact of long COVID fatigue on research in this area. ME/CFS is pulled out as an example of a condition in which chronic fatigue is one of the symptoms to highlight and compare the struggles of people who have been living with fatigue for a long time, but the feature is not intended to be specifically about ME/CFS. I have amended the text to clarify this.

Dawn Connelly

Features editor

The Pharmaceutical Journal

It's blatantly obvious you've never met anyone suffering from CFS/ME. As a sufferer myself, I can honestly say that PEM is NOT EVEN CLOSE to being the main symptom.

I thought the article made it clear that the relation between CFS & the scope of the article refers to the symptom of fatigue...Which is BY FAR the main debilitating symptom of the condition. (not just in my opinion, but EVERY person I've ever heard talk about it. I'm a member of a Facebook support group where thousands of CFS sufferers post about their difficulties.)

The article even mentioned how many people aren't even aware they experience PEM. I myself have never considered it a symptom due to the unrelenting fatigue I'm already constantly battling.

You made it sound as if ME/CFS sufferers primarily experience fatigue post exertion. (Or even that exertion is REQUIRED for fatigue symptoms).... Which is not the case whatsoever.

So, if anyone needs to watch out about spreading incorrect info, that's you my friend.

The author of this clearly has a deep understanding of how CFS affects the lives of those burdened with this illness.

As this is primarily an article about about ME/CFS please could you consider making this clear in the title - as many health professionals do not understand that there is a major difference between having ME/CFS and having chronic fatigue

Chronic fatigue is a very common symptom that occurs in a wide range of medical and mental health conditions. It is not a distinct clinical entity

ME/CFS is a syndrome that includes activity-related fatigue and post-exterional malaise/symptom exacerbation among its key diagnostic features

The new NICE guideline sets out a very clear list of symptoms that are required to make a diagnosis of ME/CFS:

All of these symptoms should be present:

Debilitating fatigue that is worsened by activity, is not caused by excessive cognitive, physical, emotional or social exertion, and is not significantly relieved by rest.

Post-exertional malaise after activity in which the worsening of symptoms:

--- is often delayed in onset by hours or days

--- is disproportionate to the activity

--- has a prolonged recovery time that may last hours, days, weeks or longer.

Unrefreshing sleep or sleep disturbance (or both), which may include:

--- feeling exhausted, feeling flu-like and stiff on waking

--- broken or shallow sleep, altered sleep pattern or hypersomnia.

Cognitive difficulties (sometimes described as 'brain fog'), which may include problems finding words or numbers, difficulty in speaking, slowed responsiveness, short-term memory problems, and difficulty concentrating or multitasking.

Dr Charles Shepherd

Hon Medical Adviser MEA

Member of the NICE guideline on ME/CFS committee from 2019 - 2021

Thanks for your helpful comments on our feature. The feature aims to explore what is known about fatigue in general, and the specific impact of long COVID fatigue on research in this area. ME/CFS is pulled out as an example of a condition in which chronic fatigue is one of the symptoms to highlight and compare the struggles of people who have been living with fatigue for a long time, but the feature is not intended to be specifically about ME/CFS. I have amended the text to clarify this.

Dawn Connelly

Features editor

The Pharmaceutical Journal

I've already commented above to someone who left a similar comment, so if you don't mind pls read that as well.

It's really scary to me that PEM is such a huge factor to the medical "expert" community... So much so that it's considered a requirement for diagnosis.

As I mentioned above, I've never considered "exertion" to be much of a factor when considering my symptoms. Sure, when I have to go do things I'm worn down even more afterward, but even if I lay around for days trying to rest up I'm still going to be fatigued!!

You could say that I'm only one person & insist most people would consider exertion to play a big role in symptoms, but based off countless posts I've read on the CFS/ME support group Facebook page that's not the case with them either!?!

The reason I'm so bothered by this is because it's just one more thing added to the confusion/misinformation surrounding this cursed illness. I'm aware that there's been a severe lack of funding for research which in turn resulted in very little studies being carried out. However the ones that have been done have obviously caused erroneous info to spread throughout the medical community.

I'm going to assume that what was actually meant by post exertional malaise was really just trying to say that activity does not help the symptom of fatigue.

Another thing that seems to be creating problems with research is how there's no distinction between severity levels. It doesn't seem right, in my opinion ,to group together people who are still able to work and function practically normally and those who can barely leave their bed.

I'm not trying to be rude... It's just that this condition has completely stolen my life. I'm alive but I don't consider this living. I desperately yearn for real progress to be made regarding CFS but the way things stand currently (esp the lack of real understanding by doctors) gives me little hope.

If only there were more truly insightful people, like the author of this article working to make progress concerning CFS/ME.