clinicaltrials.gov

Source: istockphoto.com

Clinical trial organisers pay volunteers in cash for attending medical check-ups

Shirin Abdul Khan was 16 years old when in 2009 she was enrolled as a volunteer in a clinical trial to study the effects of adding vitamin D to conventional treatment for patients newly diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis. Along with many of her school friends, she was lured by the easy money.

“It was harmless,” Khan says. “We just had to sign a blank form every time the money was given. Whenever I had to go for a check-up, once a month, they would pay us 150 rupees (US$2.50). It was good money for a school student.”

She decided to enrol after hearing about her aunt’s treatment for cancer. Sairabano Khan was part of a clinical trial in 2008 to study the safety and efficacy of a new compound for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

Sairabano Khan received 700 rupees (US$11.00) at home each time she went for a check-up at the Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital in Pune. This was one month’s pay for someone who used to do household chores. She had to stop work because of her illness, and the trial money helped her make ends meet.

There are many such cases in India of money changing hands as volunteers enrolled in trials. However, the companies failed to seek adequate consent from participants in some trials. Sometimes the consent papers were in English, which most patients in rural areas cannot understand, and representatives didn’t explain the many risks associated with the trial.

In 2013, India’s Supreme Court took action after receiving complaints and public-interest litigation (PIL) petitions filed by non-government organisations (NGOs). All trials of new drugs were subsequently put on hold. However, the Indian government convinced the Supreme Court that the move was not in the interest of patients who needed new drugs. The Supreme Court acceded, but imposed a three-tier screening process for all trials. Since then, the Ministry of Health has laid down fresh rules and amended existing legislation to tighten the regulatory control of clinical trials (see ‘Timeline of clinical trials in India’). But uncertainty over the new regulatory regime has led pharmaceutical companies and contract research organisations (CROs) to move their clinical trial programmes elsewhere.

Procedural violations

Since regulations in India were amended in 2005 in a bid to liberalise the conduct of global drug trials, companies have flocked there because of the genetic diversity of the population. However, trials in the country have been plagued by scandal. Government data show that more than 2,600 patients participating in clinical trials in India died between 2005 and 2012, and nearly 12,000 suffered serious adverse effects. Of these, 80 deaths and more than 500 serious adverse effects were directly attributed to the drug being trialled.

It was a 2009 US$3.6m post-licensure observational study, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which finally prompted regulatory change. The study, which aimed to evaluate the cost and feasibility of introducing the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine into the country’s universal immunisation programme, was run by the Programme for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), a non-profit organisation based in Seattle in the United States, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in New Delhi, and the Indian state governments of Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat. The trial, which involved 24,777 adolescent girls, was halted by the ICMR in April 2010 following media reports of the deaths of seven participants and a memorandum from 68 human rights and women’s groups to the Indian Minister of Health and Family Welfare opposing the trial’s “unethical” nature[1]

.

The media came down hard. The government had to finally concede defeat

“The media came down hard,” says Chandra M Gulhati, a healthcare activist in New Delhi and editor of the Indian medical journal Monthly Index of Medical Specialties. “The government had to finally concede defeat.”

The deaths were not found to be causally associated with the vaccine. However, Vishwa Katoch, director-general of the ICMR, admitted to India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare in April 2010 that the guidelines laid down by the drug controller general of India (DCGI) had not been adhered to during the trial. The DCGI works for the health ministry and is responsible for approving new drugs, clinical trials and medical devices, as well as monitoring the quality and efficacy of pharmaceutical products on the market.

After little action by the Indian Government, the women’s health activists who had brought the case to the attention of the Indian Parliament filed a PIL petition in the Supreme Court about unethical promotion of the vaccines in the private and the public sector, violation of rules on informed consent and the need to investigate the deaths and adverse events after vaccination. Those required to respond to the petition included the DCGI, the ICMR, the states of Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat, PATH International, and the vaccine manufacturers. A second petition on the HPV vaccination project was jointly filed by two NGOs — SAMA, a resource group for women and health, and the Karnataka-based Drug Action Forum — and Delhi Science Forum. These petitions came on the back of earlier PIL petitions on clinical trials filed by NGO Swasthya Adhikar Manch, and doctor and whistleblower Anand Rai.

In a report published in August 2013, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare said that PATH had violated laws and regulations laid down for clinical trials in India while conducting the HPV trial, and accused it of promoting the interests of HPV vaccine manufacturers, who would have reaped huge profits had the vaccine been included in the universal immunisation programme[2]

. The report was also critical of the ICMR, which forms ethical guidelines for researchers, pointing out that its involvement in the study gave rise to a conflict of interest.

In a statement, PATH stressed that it strongly disagreed with the findings, conclusions and tone of the report, which it said disregarded the evidence.

Supreme Court intervention

In September 2013, India’s Supreme Court stepped in, ruling that no clinical trials should be allowed for new drugs until a mechanism is put in place to monitor them.

Because of the increasing number of deaths and public concern across the country, all trials were held in abeyance

“[Because of] the increasing number of deaths and public concern across the country all trials were held in abeyance,” says Gulhati, who is also a former World Health Organization consultant on drugs. “Trials were never banned completely.”

The immediate consequence of the Supreme Court’s actions was that the number of new clinical trials dropped dramatically. Data from the Indian Government show that the number of applications to conduct clinical trials in India fell from 480 (with 253 approved) in 2012 to 207 (with 73 approved) in 2013.

Since the Supreme Court’s decision, 162 trials approved by the DCGI have been put on hold. A senior official of a multinational drug company says this has been a major setback.

Speaking at BioAsia 2015, an annual international life sciences conference held in Hyderabad, India, in early February 2015, an official from the CRO Quintiles said there were several hundred clinical trials taking place in the country before 2010 that were in complete compliance with international and local guidelines. Quintiles currently has approval for ten trials in India but commenced just one trial in 2014. Many CROs say that conducting clinical trials in India is now difficult and cumbersome, and have not gone ahead with trials despite getting government approval.

Leena Menghaney, access campaign coordinator at humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), says that for the past two years, MSF has not had the clearance it needs to conduct operational research on HIV patients living with tuberculosis.

Gulhati insists that trials are still going on in India under the new rules, but that approvals for trials are taking much longer. “It is an ongoing exercise, since the Ministry of Health is issuing new orders to take into consideration the directives issued by the Supreme Court,’’ he says.

The Supreme Court has stripped the DCGI of powers to approve clinical trials. “The Supreme Court asked for a mechanism to be put in place. There is a three-tier system now for all trials. There is a subject committee of 10-12 members for each therapeutic area, a technical committee, which has 20 members, and an apex committee,’’ Gulhati explains. “Only when all the three approve the trial can the application go to the DCGI.”

Gulhati says the new rules are aimed at ensuring that patients are not misled. He alleges that of 100 trials that took place before the Supreme Court stepped in, informed consent was perfunctory in at least 80. “It was not worth the paper it was written on, since most did not detail the side effects, or the compensation amount. It was just permission given by the patient to allow the company-appointed investigator to treat them.”

Informed consent must now be audio and video recorded. It has become difficult for multinational drug companies to dodge accountability if trials of their patented drug lead to adverse reactions, says Gulhati.

Mary Francis, director of Jovis Clinical Research, a clinical research consulting and training company based in Mumbai, and chief executive of CRO Mascot Spincontrol, says that since the new rules were introduced, the process of registering with the DCGI and Clinical Trials Registry has become more time consuming. “All the approvals have to be in place. Some new investigators don’t have proper infrastructure, or their insurance papers are not in order. If the drug is the first line of treatment in the market (a new chemical entity), it takes a longer time,’’ she adds.

An official with Scientia Clinical Services, a CRO base in Pune, questions the need to have investigators and sites registered before each trial, as has been mandated by the government, and says the many ‘must-haves’ in the new regulations are mind-boggling.

“Sponsors do not have the power to choose any investigator or a particular site. The power to do so rests solely with the regulator,” he says. “If one denotes any hanky-panky, or if the regulator is dissatisfied about the credentials, the trial could be refused.”

The official adds that the registration of sites and investigators will take more time. “A simple back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that around 12 months would be lost just for the registration process,” he claims.

Global spread of clinical trials

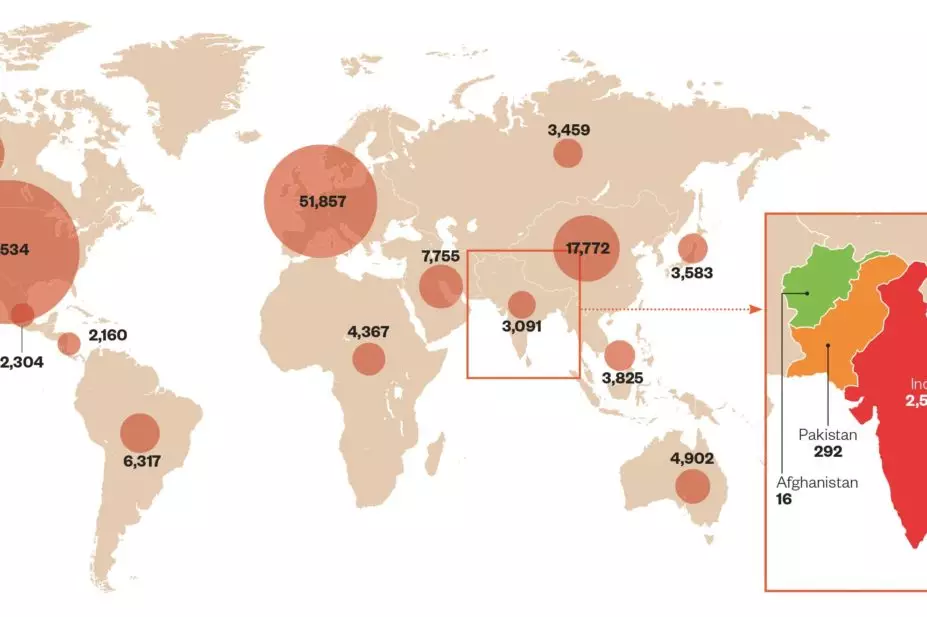

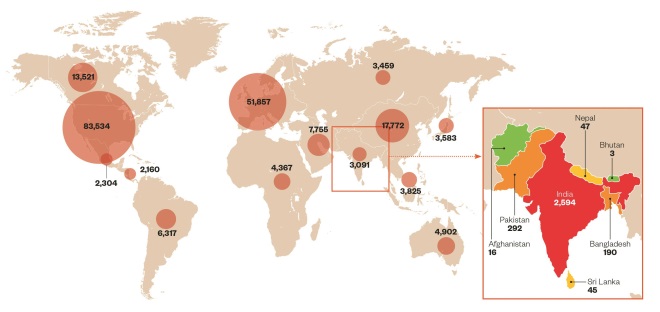

Source: clinicaltrials.gov

Data from clinicaltrials.gov show that 1.4% of global clinical trials are currently carried out in India compared with 3.2% in China, 1.5% in the Czech Republic, 1.0% in Turkey, and 0.9% in Thailand. Half of all trials being conducted worldwide are based in North America, with the UK hosting 5.5% of trials (data retrieved on 11/03/2015).

More compensation

“The number of trials has reduced considerably because of the Supreme Court’s intervention. Also there is greater compensation,” Gulhati says. “Patients will now get at least four times more than they would have got before.”

The health ministry is currently working on a clinical-trial policy that will incorporate quicker approvals and balanced compensation guidelines. “The baseline figure of 800,000 rupees (US$13,000) as per the formula can result in actual compensation of 400,000 rupees (US$6,500) for patients over 65 years old with a short period of expected survival and a maximum of 7.29 million rupees (US$0.1m) for young volunteers in phase 1 trials. Earlier, the compensation was 50,000 rupees (US$800) with a maximum of 300,000 rupees (US$5,000),” he says.

However, he adds that determining the cause of death is dependent on the integrity of the investigator: “There are over 30,000 investigators in India — how many are honest and how many are corrupt?” No sponsor would like to publicise unfavourable results, says Gulhati, and there is a conflict of interest because investigators are employees of the sponsor and would find it difficult to file an adverse report. “There is no independent mechanism,” he adds.

Pulling out

Given the uncertain regime, drug companies and CROs are cutting back on clinical trials in India. The Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance (IPA), which represents leading domestic pharmaceutical companies, says that the increasing reluctance of India’s drugs and devices regulator to grant approvals for new drugs, even if they are approved in developed countries, and to allow clinical trials or biostudies for export purposes, has severely hampered the industry.

The hub appears to have shifted to China, where a lot of government support has come to the aid of the industry, in terms of easier processes

Francis says that some trials have moved to other countries. “The hub appears to have shifted to China, where a lot of government support has come to the aid of the industry, in terms of easier processes. English has also been made mandatory in China, which has given a fillip to most CROs to take on work from multinationals.”

She says it is easier to conduct business outside India. “CROs in Turkey, Indonesia and Malaysia are flourishing, since the regulatory norms are not so strict and approvals are given faster,” she says, adding that CROs in Eastern Europe have made it cheaper to carry out clinical trials there.

“From 2010–2011, things have changed quite drastically for CROs. These regions [Eastern Europe] used to charge heavily, so many of the multinational companies moved to India, where it was 40% cheaper to conduct trials and there was a ready demographic,” she explains. “Now, the margin has come down considerably.”

The effects of the regulatory uncertainty are already being felt. Max India, for example, has announced that it will sell its clinical research business for US$1.5m to JSS Medical Research, a Canadian CRO. The company says the regulatory challenges have made it difficult to scale up the business.

Other Indian pharmaceutical companies, such as Biocon, Alembic, Zydus Cadila, Torrent and Lupin, have already moved trials out of the country. At Biocon, the research and development (R&D) spend is 134% higher in the second quarter of 2015 compared with the same period in 2014. The company’s chairman, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, said at an analyst briefing that the high R&D spend is a result of ongoing global clinical trials that require large investment. For example, Biocon’s global phase III trial for biosimilar trastuzumab is being conducted in Europe.

Indian CROs, such as Veeda Clinical Research and Lambda Therapeutics, have also moved out to other Asian countries, including Malaysia and Thailand. An official at Veeda says the high degree of uncertainty in India has discouraged clinical trials.

Timeline of clinical trials in India

June 2009: Registration of clinical trials in the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) registry becomes mandatory.

2009: Non-profit organisation PATH along with the ICMR and two local governments start a phase 4 trial of human papillomavirus vaccine in adolescents in two Indian states.

April 2010: 68 Indian human rights and women’s groups send a memorandum to the Indian Minister of Health and Family Welfare opposing what they say is the unethical nature of the PATH HPV vaccine trial and calling for it to be halted. In response, the ICMR suspends the trial.

March 2011: Twelve New Drug Advisory Committees are constituted to evaluate applications for approval of clinical trials, excluding investigational new drugs (INDs). Applications for INDs are evaluated by a separate committee.

February 2012: Indore and Pune based health activist group, Swasthya Adhikar Manch, files Public Interest Litigation seeking justice for “drug trial victims throughout nation”.

January 2013: Amendments to the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules specify procedures to analyse the reports of serious adverse events occurring during clinical trials and procedures for payment of compensation in case of trial-related injury or death.

February 2013: Amendments to the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules specify various conditions for conduct of clinical trials, authority for conducting clinical trial inspections and actions in case of non-compliance. Further amendments specify requirements and guidelines for mandatory registration of ethics committees.

March 2013: The Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) constitutes an expert committee to examine reports of deaths in clinical trials.

July 2013: The Ranjit Roy Chaudhury panel — established to advise on policy guidelines for approval of new drugs, clinical trials and banning of drugs — publishes a report suggesting major changes, including that clinical trials should be held only at centres that are accredited for the purpose, and that the existing 12 drug advisory committees should be replaced by a single broad expertise-based Technical Review Committee to ensure speedy clearance of applications.

July 2013: The US National Institutes of Health announces it is suspending 40 clinical trials in India because of the uncertainties posed by the new requirements.

August 2013: Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare publishes report criticising PATH, the Indian Council of Medical Research and the DCGI over conduct of the HPV vaccine trial.

August 2013: Drugs and Cosmetics (Amendment) Bill 2013 introduced in Parliament, which contains penal provisions for violations of clinical trial procedures, and provisions for payment of compensation and ethics committees.

August 2013: The DCGI makes it mandatory for the sponsor or his representatives to furnish the details of the contract between the sponsor and the investigator with regard to financial support, fees, honorarium, and payments in kind to be paid to the investigator.

September 2013: India’s Supreme Court suspends all clinical trials of new drugs in the country.

September 2013: Contract research organisation Quintiles closes its research centre in Hyderabad, a joint venture with Apollo Hospitals Enterprise.

November 2013: The DCGI issues a directive that an audiovisual recording of the process of obtaining written informed consent is required for each trial subject.

January 2015: The health ministry proposes pre-submission meetings in a bid to enable technical deliberations between stakeholders and the drug regulator before clinical trial applications are submitted.

Ease of doing business

In January 2015, in response to Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s plan to make it easier to do business in India, the health ministry proposed pre-submission meetings in a bid to enable technical deliberations between stakeholders and the drug regulator. The meetings will take place before drug companies make a formal application for clinical trials. The move is expected to enhance efficiency in the sector, given its muted growth over the past two years, and increase transparency, predictability and accountability.

For some time, drug companies have been asking for an opportunity to carry out technical deliberations with the regulator and experts before submitting an application to conduct a clinical trial. A health ministry official says it would at least ensure that a discussion takes place about the regulatory pathway, and that companies would be able to make their applications in a more systematic manner, saving time and resources for both the drug company and the regulator.

But Gulhati criticises this move, which was one of the recommendations of Ranjit Roy Chaudhury’s expert committee formulated by the government in 2013 to advise on matters related to policy and guidelines for the approval of new drugs and clinical trials[3]

. Gulhati says the committee is “highly pro-industry (pro-clinical trials) and anti-patient”. Speaking about a major conflict of interest, he says: “Ranjit Roy Chaudhury is employed at the Apollo Hospital heading clinical research. The hospital is one of the biggest private-sector clinical site management organisations. How can he review the situation and file a report aimed at helping draft the new rules?”

Francis says the regulation of clinical trials in India is uncertain compared with other countries. “Comparatively, it is very certain abroad, since everything is on the website, the timeline and the procedure. Here [in India], nothing is clear.”

To counter the many loopholes that still exist in India, Francis suggests that more experienced people are needed in CROs. “Training needs to be conducted so that people can understand the legal aspects, and understand how approvals are given, the regulatory monitoring, as well as the ramifications,” she says.

However, some doctors say that clinical research in India is of a high standard and that deaths during clinical trials are to be expected. Parag Shah, who heads the male infertility clinic at Nowrosjee Wadia Hospital in Parel, Mumbai, says: “Unfortunately, the good that has come of clinical research for several thousands of patients in India is often overlooked.’’

He added that the percentage death per population, and not absolute numbers, should be an important consideration.

Francis agrees: “We cannot say that [deaths in clinical trials] do not happen in other countries. Deaths due to clinical trials happen everywhere. One has to see it in perspective.”

She adds: “A few rotten apples here, though, and everyone is crucified. Many CROs are actually doing genuine work. The few who disregard the norms get the spotlight.”

References

[1] Sama: Resource Group for Women and Health. Memorandum to the Health Minister on World Health Day opposing HPV vaccinations . April 2010.

[2] Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Seventy-second report on alleged irregularities in the conduct of studies using Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine by PATH in India. August 2013.

[3] Report of Professor Ranjit Roy Chaudhury expert committee to formulate policy and guidelines for approval of new drugs, clinical trials and banning of drugs. July 2013.