Adrià Volta

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, it became apparent that some communities in the UK were being hit particularly badly by the virus. However, as researchers rushed to find treatments, they also grappled with the fact that the very groups of people who were most affected — ethnic minorities and those living in deprived areas — were also the ones that were historically underrepresented in clinical trials[1].

Participants of diabetes trials, for example, are often not the ethnically diverse populations that are typically seen in clinical practice[2]. The same is true for trials of cardiovascular, cancer and dementia drugs[3–6].

The reasons for this ethnicity research gap are complex but likely to be a mix of hesitancy from participants, healthcare staff or researchers not approaching patients — with invitations sometimes not even being made in different languages — as well as other socio-economic factors and entrenched structural inequalities[7]. The consequences of these discrepancies are potentially huge in that the benefits and harms recorded in trials may not translate to clinical practice, which means findings specific to different populations may be missed, ultimately contributing to widening health inequalities.

So, when the University of Oxford’s ‘PRINCIPLE’ trial, launched in March 2020 to test the effectiveness of pre-existing drugs in older people with COVID-19, needed to recruit quickly and from the community — in particular the marginalised communities that were most vulnerable — pharmacies were included as an instrumental part of the effort[8].

As the university’s pharmacy inclusion and diversity lead at the time, Mahendra Patel set to work doing outreach with religious and cultural groups, local government, university students, people with disabilities and organisations large and small (even involving 1990s TV fitness instructor ‘Mr Motivator’).

The efforts led to 10,000 patients being recruited over two years, and this same approach was repeated when the ambitious ‘PANORAMIC’ trial was launched in 2021 to test novel antivirals. It has since signed up 27,000 patients[9].

Patel’s aim was to get pharmacies on board on a scale that had never been done before. From large multiples to independents, more than 7,500 community pharmacies were promoting PRINCIPLE to their patients and, by the time PANORAMIC came around, this number had increased to 8,600 across the UK.

“There was a lot of learning from these innovative platform trials,” says Patel. “We were bringing research participation into the comfort of people’s homes.”

Pharmacy networks had a big impact and, in my opinion, had never been mobilised before

Mahendra Patel, head of the Centre for Research Equity, University of Oxford

Pharmacies were visible and open, and in the very communities they needed to reach, were able to both spread the word, answer questions and refer possible patients, he adds.

“Pharmacy networks had a big impact and, in my opinion, had never been mobilised before. I just went around asking the national multiples, local pharmacies, colleagues, anyone I could think of to try and improve the visibility of these trials.”

Boots, LloydsPharmacy and Well were among those displaying posters in their windows, but it went beyond putting out promotional materials, according to Janice Perkins, former superintendent pharmacist at Well. “We put posters up and handed out flyers, but it is also about targeting your message, having that conversation with somebody to say there is an opportunity here, to explain why it would be important, reassuring people. That personal invitation, that’s how we had success.”

Building on the momentum

Data from PRINCIPLE show good representation compared with national census data for South Asian populations and across socio-economic profiles (see Box)[10]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic was a unique time, with researchers and potential trial participants pulling together to fight the novel virus.

Box: Promoting diverse participation in ‘PRINCIPLE’

Several strategies were employed to promote recruitment into the PRINCIPLE study from socio-economically deprived and minority ethnic communities:

- A national pharmacist expert was appointed and tasked with: targeting socio-economically deprived areas, minority ethnic communities and people with learning difficulties; developing UK-wide relationships with community and religious organisations; collaborating with universities and national and regional healthcare institutions; and gathering nationwide support from minority ethnic leaders, healthcare professionals and their organisations;

- The trial was consistently promoted in many languages, via local and UK national media channels, the internet and social media platforms;

- Pharmacy and general practice networks helped to promote and facilitate recruitment.

The strategies contributed to the inclusion of 4.0% South Asian and 0.5% black participants in the analysis of azithromycin for treatment of suspected COVID-19, which was comparable to 3.7% Asian ethnicity and 1.6% black ethnicity among people aged over 50 years (the target age group) in England and Wales.

The proportions of participants in Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintiles were (from most to least socio-economically deprived): 26% (IMD1), 19% (IMD2), 20% (IMD3), 18% (IMD4) and 17% (IMD5), showing good recruitment from socio-economically deprived communities.

To build on this momentum, the University of Oxford launched the ‘Centre for Research Equity, through pharmacies, community and healthcare’ in May 2023, led by Patel and colleague Chris Butler, clinical director of the University of Oxford Primary Care Clinical Trials Unit. The centre lists pharmacies among the stakeholders that can provide “direct, sustained and constructive interaction with communities”.

“Let’s use this engine we have established over two years to move forward,” says Patel. “There is an issue with sustainability here and that’s where the centre comes in — we need to build on the work we have done.”

The plan is to provide training, build the evidence base for community-based recruitment and trial design and build a “delivery network” through pharmacy, community and faith groups and other healthcare providers.

“Rather than a one size fits all, it’s about tailoring to different communities and different geographies. Looking at inclusivity in the very early stages of trial development,” Patel explains.

It’s about tailoring your approach to the population you want to reach and being more inclusive and extensive in your approach to patients

Philip Evans, deputy medical director, National Institute for Health Research

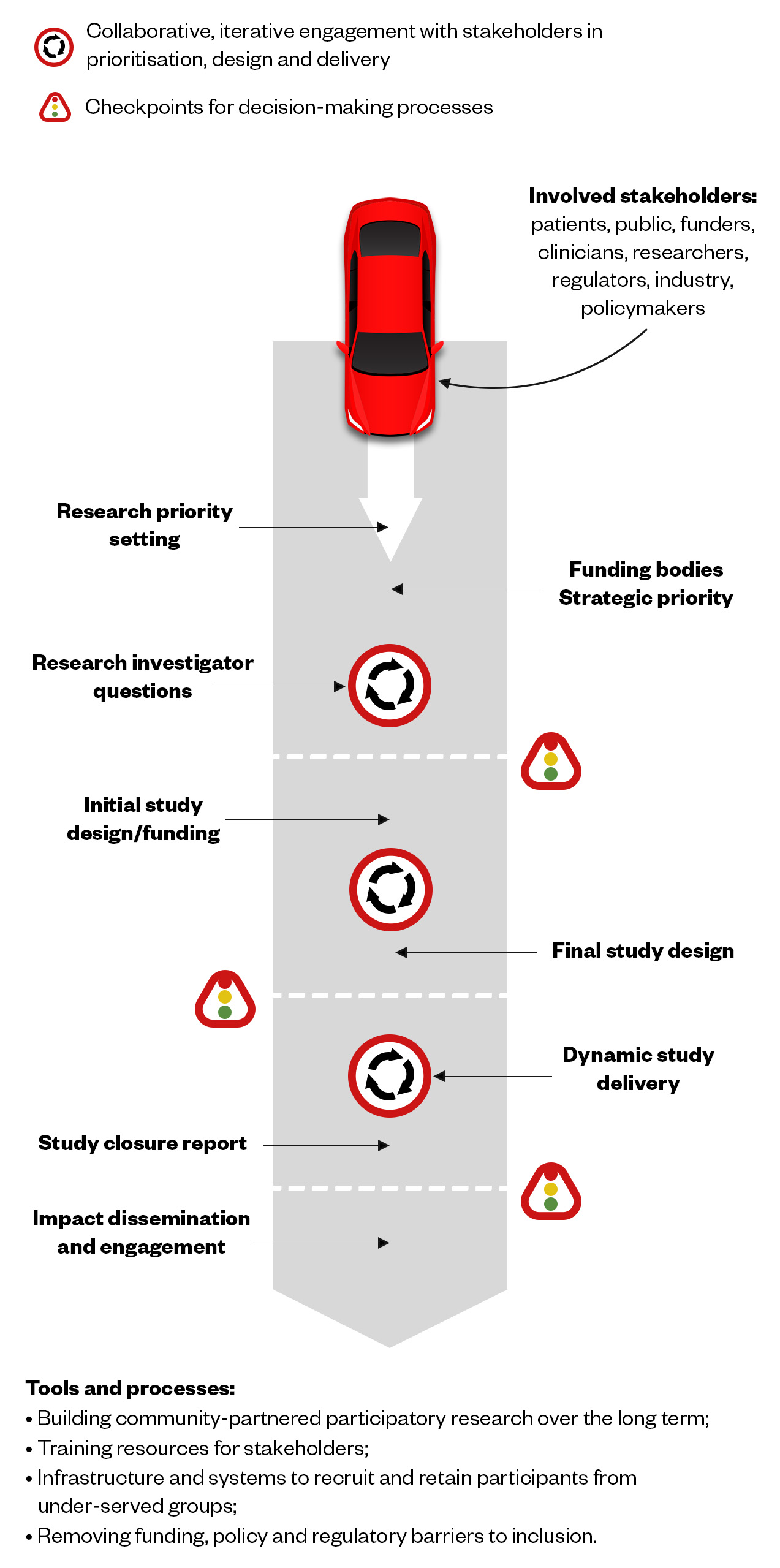

Philip Evans, a retired GP and deputy medical director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network, says it is vital that research is applicable to the population that is ultimately going to be treated[11]. That can be in terms of gender, ethnicity, age, deprivation and prevalence of conditions, he adds. The NIHR has developed guidance for researchers on how to address this, he says (see Figure 1)[12].

The Pharmaceutical Journal, based on the NIHR original

“We’ve identified there’s a major problem with it and that’s where the centre comes in, trying to address how you differentially recruit in areas of greatest need. We demonstrated, to some degree in the pandemic, it’s about tailoring your approach to the population you want to reach and being more inclusive and extensive in your approach to patients.”

Part of encouraging pharmacies and others in primary care to get more involved is to make research “as easy as possible to do in that difficult, stressed clinical environment that we find ourselves in”, Evans adds.

Barriers to overcome

This is not the first initiative to encourage community pharmacy to take part in more research. The NIHR Pharmacy Champions programme and Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) ‘Research ready pharmacy’ accreditation scheme are two examples that started strongly but then slowly petered out.

It’s really difficult for pharmacy teams to see how they can make a contribution

Janice Perkins, chair of Greater Manchester Local Pharmaceutical Committee

There are certainly barriers to overcome, notes Perkins, who is now chair of Greater Manchester Local Pharmaceutical Committee. “I’ve always felt that community pharmacy can play a part in research [but] a lot of research projects are so complex, detailed and time consuming, it’s really difficult for pharmacy teams to see how they can make a contribution,” she says.

When she worked at Well, Perkins would try to say yes if there was research that had a clear benefit to pharmacy teams and their patients. When Patel approached her about PRINCIPLE, it was easy to see why they should get involved and they created in-house materials to help. “There are others I’ve not got involved with over the years because they are just too complicated. You need to think of the practicalities.”

This includes researchers asking themselves why they want pharmacies take part, how it benefits the patients and the community, and how it is going to have an impact on inclusion or a challenge that pharmacists know is a problem. She adds that Patel was very good at communicating how the trial was progressing.

“I’ve been involved in projects before where you don’t hear anything for two years but [with PRINCIPLE] we knew how it was going so I could feed back to the teams and say you played a part in this.”

Change is coming

Jenny Scott, senior lecturer in pharmacy at the Centre for Academic Primary Care at the University of Bristol, believes there is so much more community pharmacy can do in research and says that change is coming. In late 2022, she set up South West Pharmacy Research Network to help bring research closer to practice. She also points to the NIHR Pharmacy Research Incubator, awarded in June 2023 to a research team in Leicester, which aims to address areas where there is a need to build research capacity on a national level[13].

Recruitment through pharmacy is essential if we’re going to design services that really are fit for the diverse population that pharmacy serves

Debi Bhattacharya, pharmacist and professor of behavioural medicine, University of Leicester

Debi Bhattacharya, a pharmacist and professor of behavioural medicine at the University of Leicester, who will lead the incubator work, says pharmacy is the third largest healthcare profession but substantially underrepresented within all NIHR training and research programmes, with few pharmacy professionals adopting principal investigator roles.

In the first 12 months of the three-year incubator, Bhattacharya plans to work with pharmacy professionals, including technicians, across hospital, community and primary care to gain an understanding into the barriers and enablers to getting involved in research. Issues she expects to come across include pharmacy not seeing research as a core part of its NHS work, as well as infrastructure and funding.

“We know that wholescale changes need to happen to support pharmacy professionals across the board in participating in research,” she adds. One of the main reasons driving her team’s application to the NIHR incubator was to ensure more inclusive research, she says. “Recruitment through pharmacy is essential if we’re going to design services that really are fit for the diverse population that pharmacy serves.”

In 2022/2023, more than 1 million people took part in NIHR-funded research. The institute’s current seven areas for strategic focus include: building on the COVID-19 research response; building capacity and capability in preventive, public health and social care research; improving the lives of those with multiple long-term conditions; and bringing research to underserved regions and communities[14]. In November 2021, the NIHR associate principal investigator scheme opened up to pharmacists[15].

“Researchers are going to be trying to engage community pharmacy in more research so there are going to be more requests to take part and it’s about being able to be effective partners in that,” says Scott.

NIHR is really interested now in pharmacy-based research, which means you have access to funding streams

Jenny Scott, senior lecturer in pharmacy, Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol

Scott believes the key is collaboration from the start of a project rather than adding pharmacy at the last minute without any thought on how that might work.

“We were recruiting pharmacies in Hackney yesterday for some research and I was amazed how willing they were. Five out of six said yes and one said maybe. The difference was we went round face to face so they were able to ask us questions and we could explain how minimal it was in terms of workload.”

She adds that pharmacies are important because they are disproportionately situated in areas of high deprivation, are on the high street close to the community and, as such, are able to engage with patients — all patients — in a very powerful way.

“Pharmacies have that relationship; they know most of the people that come in and can engage with a broad range of people. But we have got work to do in supporting community pharmacy to do that.”

Culture of research

Participating in research should not be expected as a freebie pharmacies do on top of everything else, stresses Scott. “NIHR [is] really interested now in pharmacy-based research, which means you have access to funding streams. That means there should be reimbursement for all that activity so you have your time covered.”

Pharmacy as a portal to recruit a more diverse section of the population into studies is one aspect but pharmacy as a profession should also be doing more to generate the evidence base, she adds. “Historically, particularly in community pharmacy, there have been interventions undertaken which haven’t been developed on the basis of evidence and then they don’t always work. Medicines use reviews, for example, are a good idea logically but that doesn’t always translate.”

Scott wants to see a culture of research develop within pharmacy to enable community pharmacy teams to have the willingness and capacity to work with academic researchers in partnership but also be willing to do research themselves and come forward with ideas.

Neena Lakhani, senior lecturer in clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice at De Montfort University in Leicester, has been working to get community pharmacy more involved in research for years, having been one of the original NIHR pharmacy champions for the East Midlands Clinical Research Network. She is the first to admit it has been an uphill battle.

When she started working with the NIHR in 2011, there was a fundamental gap in that there was no training available for community pharmacy. “And therein lies the problem,” she says. “Community pharmacists are the most accessible healthcare professionals on the high street. We can do a lot but we have to demystify this process.”

In the East Midlands, she is still working hard to build skills, such as by sharing new research e-learning modules developed by the RPS and NIHR. Lakhani is also working with her students to create the “research-active pharmacists of the future”, partly by sending them out to do audits in community pharmacy as part of their studies. A regular newsletter that is sent to all community pharmacies via local pharmaceutical committees shares trials that might be of interest and how pharmacies can get involved.

Several studies have been conducted locally involving community pharmacy teams, for example, on screening for diabetes and cardiovascular risk or screening for blood-borne viruses in migrants, which involved ten community pharmacies in Leicester[16,17]. The NIHR has collected research it has funded to form a portal that can help community pharmacies expand and improve their services, she adds.

My vision is to make this part of the workforce development

Neena Lakhani, senior lecturer in clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice, De Montfort University

At the Clinical Pharmacy Congress, held at London’s ExCeL in May 2023, Lakhani made the case for greater pharmacy involvement in research through the development of more pilots, more funding streams and more collaboration with GP practices. In addition to better patient outcomes, it also raises the profile of community pharmacy and embeds its role in the wider healthcare system, she argues.

“We’ve been quite successful with some projects, but it’s still not getting the traction that I want to see. My vision is to make this part of the workforce development.” Like Patel, she is of the view that it is possible to build on the traction seen with PRINCIPLE and PANORAMIC.

“In the past there have been some laudable goals in terms of improving community pharmacy taking part in research, but it’s that practical thing of how you actually do that, how you tell people about it — where is the funding, how do you make those connections? We have to break all those barriers down.”

Health inequalities

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s policy on health inequalities was drawn up in January 2023 following a presentation by Michael Marmot, director of the Institute for Health Equity, at the RPS annual conference in November 2022. The presentation highlighted the stark health inequalities across Britain.

While community pharmacies are most frequently located in areas of high deprivation, people living in these areas do not access the full range of services that are available. To mitigate this, the policy calls on pharmacies to not only think about the services it provides but also how it provides them by considering three actions:

- Deepening understanding of health inequalities

- This means developing an insight into the demographics of the population served by pharmacies using population health statistics and by engaging with patients directly through local community or faith groups.

- Understanding and improving pharmacy culture

- This calls on the whole pharmacy team to create a welcoming culture for all patients, empowering them to take an active role in their own care, and improving communication skills within the team and with patients.

- Improving structural barriers

- This calls for improving accessibility of patient information resources and incorporating health inequalities into pharmacy training and education to tackle wider barriers to care.

- 1Smart A, Harrison E. The under-representation of minority ethnic groups in UK medical research. Ethnicity & Health. 2016;22:65–82. doi:10.1080/13557858.2016.1182126

- 2Khunti K, Bellary S, Karamat MA, et al. Representation of people of South Asian origin in cardiovascular outcome trials of glucose-lowering therapies in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2016;34:64–8. doi:10.1111/dme.13103

- 3Hoel AW, Kayssi A, Brahmanandam S, et al. Under-representation of women and ethnic minorities in vascular surgery randomized controlled trials. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2009;50:349–54. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.012

- 4Berger JS, Melloni C, Wang TY, et al. Reporting and representation of race/ethnicity in published randomized trials. American Heart Journal. 2009;158:742–7. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.018

- 5Godden S, Ambler G, Pollock AM. Recruitment of minority ethnic groups into clinical cancer research trials to assess adherence to the principles of the Department of Health Research Governance Framework: national sources of data and general issues arising from a study in one hospital trust in England. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2010;36:358–62. doi:10.1136/jme.2009.033845

- 6Shaw AR, Perales-Puchalt J, Johnson E, et al. Representation of Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in Dementia Prevention Trials: A Systematic Review. J Prev Alz Dis. 2021;:1–6. doi:10.14283/jpad.2021.49

- 7Redwood S, Gill PS. Under-representation of minority ethnic groups in research — call for action. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:342–3. doi:10.3399/bjgp13x668456

- 8Principle. University of Oxford. https://www.principletrial.org/ (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 9Panoramic. University of Oxford. https://www.panoramictrial.org/ (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 10Patel MG, Dorward J, Yu L-M, et al. Inclusion and diversity in the PRINCIPLE trial. The Lancet. 2021;397:2251–2. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00945-4

- 11Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2022-2027. National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2022.https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/equality-diversity-and-inclusion-strategy-2022-2027/31295 (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 12Improving inclusion of under-served groups in clinical research: Guidance from INCLUDE project. National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2020.https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/improving-inclusion-of-under-served-groups-in-clinical-research-guidance-from-include-project/25435 (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 13NIHR funds new Incubators to support research careers. National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2023.https://www.nihr.ac.uk/news/nihr-funds-new-incubators-to-support-research-careers/33586 (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 14Our key priorities. National Institute for Health and Care Research. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/our-key-priorities/ (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 15Associate Principal Investigator (PI) Scheme. National Institute for Health and Care Research. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/health-and-care-professionals/career-development/associate-principal-investigator-scheme.htm (accessed 29 Jun 2023).

- 16Willis A, Rivers P, Gray LJ, et al. The Effectiveness of Screening for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in a Community Pharmacy Setting. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91157. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091157

- 17Pareek M, Eborall HC, Wobi F, et al. Community-based testing of migrants for infectious diseases (COMBAT-ID): impact, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of identifying infectious diseases among migrants in primary care: protocol for an interrupted time-series, qualitative and health economic analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029188. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029188