“I was covered in my own blood, the operating suite was covered in my own blood, because my arm had managed to free itself from the restraints and was pouring blood everywhere,” said Barrie, a patient describing his experience of going through heart surgery without being given his Parkinson’s disease (PD) medicines, which provoked “erratic and difficult movement”.

In an interview with the charity Parkinson’s UK in May 2024, Barrie explained that — following similar problems during a previous hospital admission — an agreement was reached with hospital staff to ensure that he received his critical PD medicines on time. However, despite this agreement and the medicines being present in the operating theatre, Barrie was not given them until he returned to the ward.

I know my medication regimen better than anyone else, I know when my body needs its next dose of medications because my body tells me. They don’t have that alarm — I do

Barrie, who has Parkinson’s disease

“I know my medication regimen better than anyone else, I know when my body needs its next dose of medications because my body tells me. They don’t have that alarm — I do,” he said.

Time-critical medicines (TCMs) are medicines that need to be given or taken at a specific time, where a delay in receiving the dose or an omission of the dose entirely may lead to serious patient harm. Examples of TCMs include insulin injections for diabetes mellitus or specific medicines for PD.

Missed or delayed administration of TCMs can result in deterioration in disease control, leading to increased morbidity, mortality and/or length of hospital stay. Patients can also suffer stress and anxiety owing to an increase in symptoms and a loss of control of their condition1.

The omission or delay of medicines in the acute sector has been an ongoing issue since 2006, which was first highlighted in a rapid response report, published in February 2010 by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA).

The report revealed that the NPSA was alerted to 27 deaths, 68 severe harms and 21,383 other patient safety incidents related to omitted or delayed medicines between September 2006 and June 20092.

“People with PD need to take their medication within 30 minutes of their individually prescribed times,” explains Sam Freeman Carney, health policy and improvement lead at Parkinson’s UK.

“The consequences of not doing so can be not being able to swallow, walk or talk again, and in extreme circumstances, it can be fatal,” he says.

“But the number of patients that haven’t got their medication on time when they’ve been admitted to hospital has always remained quite stubbornly high.”

In a webinar on TCMs held by the Specialist Pharmacy Service (SPS) on 28 June 2023, Graeme Kirkpatrick, head of patient safety at NHS England, highlighted that there were 41,000 medicines incidents reported to NHS England’s national reporting and learning system under the omitted medicines category between April 2022 and March 2023. Omitted medicines accounted for 18% of all medicines incidents, the second highest category after ‘other’.

Although most of these incidents (83%) resulted in no harm, there were 17 deaths reported.

In response to the prevalence of ongoing incidents, NHS England included TCMs in its Medication Safety Improvement Programme in April 2024, a move that it announced on World Patient Safety Day on 17 September 2024.

The programme, which is aimed to address the most important causes of severe harm associated with medicines that continue to challenge health and care systems, will explore how to improve care by ensuring that patients receive their critical medicines on time, in partnership with SPS and charities, such as Parkinson’s UK.

“It’s been almost 20 years since Parkinson’s UK has been actively working on this issue, and having this national focus and profile for the first time is a big positive step in the right direction,” says Freeman Carney.

“It’s now for us to work and support the programme and ensure that it’s going to deliver for people living with PD and others who rely on time-critical medication.”

Get it on time campaign

According to the ‘Every minute counts’ report published in September 2023 by Parkinson’s UK, a 2022 audit conducted by the charity found that 58% of people with PD admitted to hospital in England did not receive their medicines on time every time, with little progress made since 2015 (see Figure 1)3.

Through freedom of information requests sent to NHS trusts in England in June 2023, Parkinson’s UK also discovered that only 52% of trusts require inpatient clinical ward staff to complete training on TCMs, with only 40% making training mandatory3.

Freeman Carney says this is an important issue for people with PD, their caregivers and loved ones. “One of the things we focused on last year, is working with charity partners whose patient population is also impacted by the need to have medication when they need it.

“Together we put out a policy report last year where it highlights the issue [and] puts forward a number of solutions.”

The campaign — ‘Get it on time’ — led by Parkinson’s UK, was launched in September 2023. In a joint statement published alongside the campaign, organisations including Diabetes UK, Epilepsy Action, the National Aids Trust, Rethink Mental Illness and the Richmond Group of Charities, with the support of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS)4 called on the UK government to “take action” via “simple solutions to deliver medications on time”5.

Examples included having self-administration of medicines (SAM) policies in every hospital across each ward, boosting the rollout of e-prescribing in hospitals and using it to monitor and report missed or delayed doses, and training all hospital ward staff responsible for prescribing and administering medicines so they know what a TCM is and who needs it.

Using e-prescribing

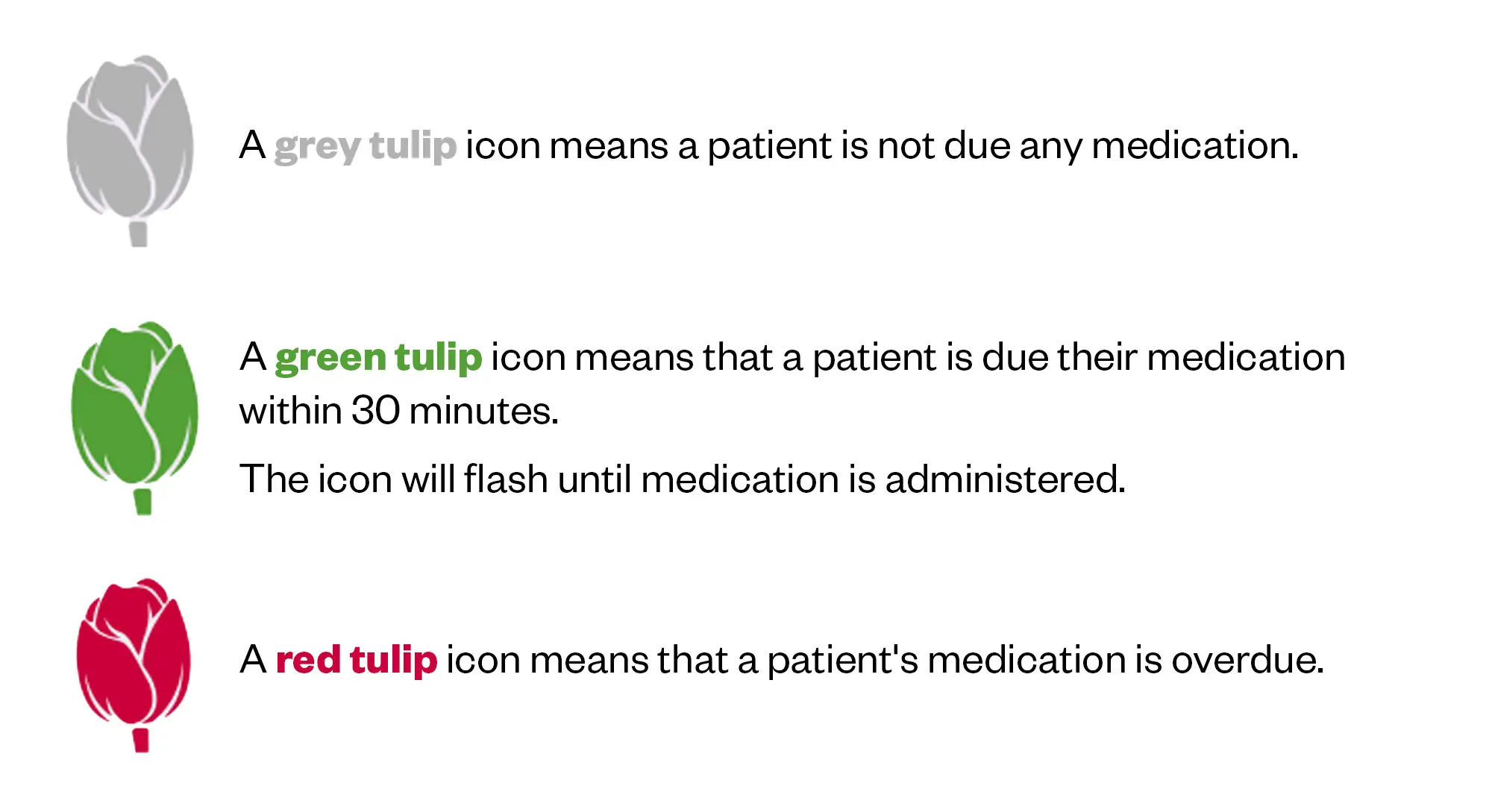

One of the key drivers for the ‘Get it on time’ campaign recommendations was a local PD project conducted by NHS Ayrshire and Arran. The project, launched in 2010, used e-prescribing to audit missed or delayed doses of medicines, create daily reports to identify patients on PD medicines, as well as develop ward prompts — known locally as ‘The Tulip System’ (see Figure 2) — to alert staff when medicines were due6.

Since The Tulip System was introduced in 2018, the initiative has led to 87% of people with PD in targeted wards receiving their TCMs on time from September 2022 to August 2023, compared with 41% in 2014. Patient feedback also highlighted improved satisfaction and confidence in staff during hospital admissions3.

Although e-prescribing is not available in every NHS trust, Freeman Carney points out that 80–90% of trusts have the e-prescribing functionality to adopt the NHS Ayrshire and Arran model for TCMs.

On 23 October 2024, NHS England told The Pharmaceutical Journal that approximately 90% of acute trusts have an electronic prescribing and medication administration system in general inpatient wards, that should have the capability to provide alerts for TCMs.

Self-administration of medicines

While e-prescribing can help with understanding the extent of problems with delayed and omitted TCMs, Emma Kirk, medication safety officer network lead at SPS, points out that it has created challenges in implementing other approaches, such as the SAM multidisciplinary process that allows patients to take control of their own medicines, which can minimise the risk of incorrect administration, improve knowledge and reduce future medicines-related hospital admissions.

However, Anna Bischler, associate director of medicines use and safety at SPS, agrees, saying that e-prescribing has had a “massive impact” on NHS trusts struggling to successfully embed their SAM policies into practice.

“When there was a drug chart and the patient could sign it, the communication between all parties was easier. I think it’s definitely more difficult now,” she says.

“There are challenges with governance and documentation. We try to sell [SAM] as it saves you time, because you don’t have to give [the medicines]. But we’ve spoken to nursing staff, and they don’t feel it actually does [save time], because they’ve still got to go through and make the record that the dose has been given on the electronic prescribing system, as patients don’t have access to this,” Bischler explains.

Despite the benefits of SAM, data from the ‘Every minute counts’ report revealed that 16% of hospitals in England do not have an SAM policy3. Of the NHS trusts with a policy, only 56% said they executed SAM in inpatient hospital wards, with 17% responding that they did not have the facilities and resources to enact their policy3.

Kirk highlights that there are several barriers to implementing SAM, such as storage — particularly of controlled drugs and refrigerated items — as well as the execution of SAM in certain wards, such as paediatrics.

For every prescribing episode, there are dozens of administration episodes, so your total opportunity for error is greater

Tony Jamieson, clinical improvement lead for medicines safety at NHS England

Other challenges with SAM include: the reliance on patients to bring their medicines into hospital, patients’ medicines being of acceptable quality and issues around accountability of administration.

“There is a huge amount of fear of putting self-administration in place, partly because — as a nurse — if the patient self-administers and you sign the chart, are you accountable for them actually swallowing it?” asks Tony Jamieson, clinical improvement lead for medicines safety at NHS England.

“For every prescribing episode, there are dozens of administration episodes, so your total opportunity for error is greater.

“There is a lot of stuff to work through … We’re really interested in what places have made this [SAM] work, what makes it work for them and [how they] manage the fear of putting SAM in place,” he adds.

Designated list of TCMs

One intervention that was stipulated in the 2010 NPSA alert and has been widely adopted by trusts is the use of a designated list of TCMs to help clinical ward staff identify patients and improve data collection2. However, experts say the impact of these lists has been limited and a national list is unlikely to be implemented, owing to variety in what constitutes a TCM among trusts1.

A designated list can guide you, but something that is time critical for one patient may not be for another

Emma Kirk, medication safety officer network lead at SPS

“A list can guide you, but something that is time-critical for one patient may not be for another,” Kirk explains.

“The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has a list and that works for an emergency department where, ideally, your patients are only there for a few hours. But this cannot be translated everywhere.”

The trust Kirk works at has 184 drugs on its TCM list, which she says can be difficult to maintain and for healthcare professionals to remember. “When the list gets that big, you’ve got a problem. And if there is a new antibiotic or PD medicine, you will probably need to add them on the list.”

Bischler adds that having a list of TCMs can sometimes have unintended consequences.

“Just one case that we’ve heard of is, when there’s a list and someone’s been asked to supply what is very obviously a critically urgent medicine, you’ve got a [healthcare] professional saying ‘well, it’s not on the list, so it’s not critical’.

“To upskill all healthcare professionals that have interactions with that individual, to be able to identify and weigh up the risk, is incredibly challenging because it’s so individualised to the scenario, to the patient and to the clinical indication. That is one of the biggest challenges,” she adds.

Involving patients

During the SPS webinar, Byrony Dean Franklin, professor of medication safety practices and policy at University College London, highlighted the importance of engaging patients, stressing that using patient held medicines records can reduce the risk of errors and serve as a reminder for administration.

“But the role that the patient can play relies on partnership with us as healthcare providers,” said Franklin.

“What we all need to do as healthcare professionals is: number one, encourage patients to keep records, if they’re able to do so; number two, ask to see them whenever we have an interaction with a patient; and number three, show them we really value it,” she added.

Speakers during the webinar also discussed the benefits of using ward posters to raise awareness of TCMs as well as relieving workforce pressures by using ward medicines assistants to administer medicines.

Improvement programme

NHS England’s involvement with TCMs has been a long time coming. Kirk explains that competing priorities within the NHS, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and workforce issues, as well as difficulties with data collection around TCMs, have contributed to the delay.

The three-year Medicines Safety Improvement Programme has started with an inquiry to gather information on various interventions already in place across England.

“Our partner organisation SPS is leading this piece of work for us because it’s already done some incredible work with one of its national webinars, and it’s put together some resources on its website,” says Jamieson.

The inquiry will involve structured interviews with organisations and local trusts who have undertaken work around TCMs to understand how they have engaged with patients, what interventions they have made and what they have measured to show they made a difference, Jamieson adds.

“You have to try to find things that are replicable … then we’ll spend a few months in the design phase where we analyse everything that we’ve got in order to offer the service to somebody else to give it a go,” says Jamieson.

While there are many challenges still to be addressed with current interventions to improve timely administration of medicines, James Davies, director for England at the RPS, says that pharmacists and pharmacy teams have a key role to play in supporting the accessibility of TCMs, whether they are self-administered or given by staff.

“One of the areas that we are exploring is the support for schemes that encourage people to take their medicines into hospitals with them, such as the ‘Green Bag Scheme’ and patients’ own drugs schemes,” he says.

“Seeing more pharmacists involved in supporting these schemes and educating other healthcare professionals on what to do, why it’s important and why it’s a problem going forward. That’s key to what we do.”

Bischler adds that to solve these longstanding problems with TCMs, a shared approach among healthcare professionals is needed. “You’re not going to fix this problem by looking at individual actions or processes,” she says. “It’s a collaborative approach and accepting that you cannot solve it unless you take iterative little steps.”

- This article was amended on 25 October 2024 to update Emma Kirk’s job title, and to clarify and provide more context to Kirk and Bischler’s comments in the ‘Self-administration of medicines’ section of the article

- This article was amended on 28 October 2024 to clarify that it is Parkinson’s UK’s ‘Get it on time campaign’ and the organisations who were involved in the joint statement.

- 1.Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Time Critical Medications. Royal College of Emergency Medicine. November 2023. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://rcem.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Time_Critical_Medications_QIP_Information_Pack_2023_Final.pdf

- 2.National Patient Safety Agency. Rapid Response Report. NHS National Patient Safety Agency. February 24, 2010. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://www.cas.mhra.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAttachment.aspx?Attachment_id=101086

- 3.Parkinson’s UK. Every minute counts: Time critical Parkinson’s medication on time, every time. Parkinson’s UK. September 2023. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-09/CS4006%20Get%20it%20on%20time%20policy%20report_Web%20Version.pdf

- 4.Parkinson’s UK. Get It On Time campaign gathers momentum. Parkinson’s UK. December 20, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/news/get-it-time-campaign-gathers-momentum

- 5.Parkinson’s UK. Joint statement: Medication on time, every time: people shouldn’t fear going into hospital. Parkinson’s UK. September 2023. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-09/Joint statement September 2023.pdf

- 6.Parkinson’s UK. Electronic prescribing: how it can improve the delivery of time critical medications. Parkinson’s UK. February 16, 2024. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/electronic-prescribing-how-it-can-improve-delivery-time-critical#:~:text=Events-,Electronic%20prescribing:%20how%20it%20can%20improve%20the%20delivery%20of%20time,improving%20patient%20care%20and%20safety.&text=Here%2C%20Nick%20Bryden%2C%20Parkinson’s%20Nurse,Digital%20Services;%20and%20Nick%20Bryden.

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

It was interesting to see a severely hyperkalaemic patient's patiromer being delayed to the next day because it had been prescribed as a morning dose on EPMA.