JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

At the time, the National Institute for Health and Care EÂxcellence (NICE) 2014 guideline on atrial fibrillation (AF) was billed as a “major advance” in the drive to ensure that many more patients at risk of stroke were taking anticoagulants[1]

[2]

. And it has certainly changed the care given to patients diagnosed with this condition.

In this guideline, NICE recommended that new direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) — such as dabigatran and rivaroxaban — should be placed alongside warfarin as first-line therapy. Unlike warfarin, DOACs have a predictable therapeutic response, rapid onset of action, few drug interactions and no requirement for coagulation monitoring. The guideline led to a massive increase in patients with AF taking anticoagulants.

“If you look back over the past five years, [we’ve gone from] about 40% of the AF population [taking anticoagulants] to 84% of the AF population [in England],” explains Matthew Fay, a GP with a special interest in cardiology and a member of the NICE guideline development group.

According to data from NHS Digital, prescriptions for DOACs overtook those for warfarin for the first time in 2018, with 9.3 million items for DOACs dispensed in the community in England compared with 8.2 million for warfarin.

However, concerns have been raised that patients taking DOACs are not receiving the support they should be.

While warfarin users are required to have frequent reviews, this is not the case for the increasing number of patients taking DOACs. Fay believes there is a ‘fire and forget’ approach to prescribing DOACs, which means that some patients are left on inappropriate doses, resulting in more strokes and bleeds. Other experts have expressed concerns that the lack of monitoring might lead to poor adherence, which is problematic with DOACs because their anticoagulant effect fades rapidly after 12 to 24 hours[3]

.

Recognising the risk

Patients are also being left on potentially risky combinations of anticoagulants and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or anticoagulants and antiplatelets, without gastroprotection — both of which increase the risk of bleeding.

However, the dangers of anticoagulants are now starting to be recognised by the government and pharmacists are being seen as part of the solution.

Results from a 2018 study showed that anticoagulants, NSAIDs and antiplatelets cause more than a third of hospital admissions as a result of avoidable adverse drug reactions, and anticoagulation was consequently identified as a patient safety priority area for NHS England and NHS Improvement[4]

.

Anticoagulation is one of six ‘headline issues’ to be addressed by the new NHS Improvement Medicines Safety Programme, details of which were published on 2 July 2019[5]

. Under the programme, pharmacists will be trained in shared decision making so that they can support patients with AF taking anticoagulants.

Audits on anticoagulation will also form part of the Pharmacy Quality Scheme for 2020/2021, according to the community pharmacy contractual framework which was published in July 2019. Similarly, in the five-year framework for GP contract reform, published in January 2019, anticoagulation is mentioned as an area in which pharmacists can take “a central role”.

‘Set adrift’

Eve Knight, chief executive of Anticoagulation UK, a charity dedicated to the pÂrevention of thrombosis, says that there is a perception that DOACs do not need monitoring “and that can be taken literally across the board”.

She adds that patients who feel like they have been “set adrift” on DOACs frequently contact the organisation.

Patients on DOACs don’t know what they can and can’t do…or…when they’re going to be seen again

“They don’t know what they can and can’t do, they don’t know if they need to make changes or not, and they don’t know when they’re going to be seen again.”

Although DOACs do not need the same level of monitoring as warfarin — patients taking warfarin require regular blood tests in order to track how long it takes their blood to clot — patients taking DOACs still need support with their medicines. DOACs require dosage adjustment if kidney function changes and are associated with poorer adherence than warfarin, so both of these areas need to be monitored[6]

.

David Russell, a pharmacist manager of a Well Pharmacy in Grenoside, Sheffield, who runs a warfarin-monitoring clinic, says there should be more routine support for patients who are switched to these newer anticoagulants.

“One of the problems at the moment is that warfarin is viewed as high risk — because it always has been — but I don’t think the same sort of risk is applied to other anticoagulants because there’s not the [same] monitoring required,” says Russell.

Fay adds that another issue is that GPs are not funded to monitor dosing of aÂnticoagulants.

“They follow what the hospital tells them and seem to forget the fundamental truth that they are responsible for that prescription. [A low dose of] 2.5mg apixaban [may be] started in hospital if the patient is unwell and losing weight … [but] when they return to their GP once they’ve put the weight back on and their creatinine has fallen, they get left on 2.5mg.

“These patients then suffer more strokes and more bleeds because of inappropriate dosing — you’ve got to make sure the dose is appropriate.”

Sotiris Antoniou, consultant pharmacist in cardiovascular medicine at Barts Health NHS Trust and chair of the International Pharmacist Anticoagulation Taskforce (see Box), agrees that it is important not to assume the dose patients are initiated on is the appropriate one. “We’ve seen evidence that, for people initiated on DOACs, basing dose on [estimated glomerular filtration rate] can lead to an inappropriate dose. We should be dosing based on Cockcroft-Gault [creatinine clearance].”

He adds that issues around dosing also cause problems during transfer of care. Some patients who are started on DOACs in secondary care may not see their GP for 12 months until they are scheduled for a blood test to check kidney function.

“Like any other drug you start on … there might be a few ‘hiccups’ in the first few weeks or months. Surely there should be some follow-up in primary care when someone’s been started on a new drug in secondary care,” suggests Knight.

Russell says that if all community pharmacies had access to GP clinical systems, as his pharmacy does, it would allow pharmacists to review the blood test results of patients taking anticoagulants and flag any issues with kidney function and potential need for dose adjustments.

The technology is there to allow pharmacists to have access to the records that they need to provide a patient management service for anticoagulation

“We need to see a shift to a patient management service for anticoagulation as a whole … the technology is there to be able to allow pharmacists to have access to the records that they need to provide that sort of service, and patients like coming in and chatting to the pharmacist about their drug regimens.”

Pharmacists working in GP practices are also well placed to review patients taking anticoagulants. Satinder Bhandal, a senior clinical pharmacist and specialist in anticoagulation working at the Swan Practice in Buckingham, says pharmacists should be asking patients directly how often they are taking their anticoagulants and if they have had any unprovoked bleeding.

“Patients wouldn’t necessarily tell anyone and [healthcare professionals] don’t automatically think to ask.”

They can then ensure that a patient’s anticoagulant is at the right dose for them by checking their creatinine clearance, she adds.

Fay agrees, saying that with GP practices now employing more pharmacists, they can be the ones to review patients taking anticoagulants and raise any issues with the GPs.

Risky combinations

It is not just dosing that needs monitoring; potentially harmful drug combinations are also a concern. The risk of harm from anticoagulants is further increased if they are prescribed concurrently with other medicines that can increase the risk of bleeding, such as NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs.

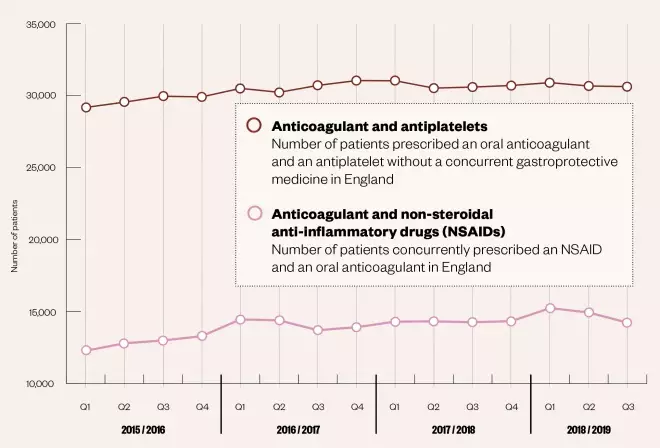

Yet figures show that during the third quarter of 2018/2019, around 14,000 patients in England were prescribed an NSAID alongside an anticoagulant, and 30,000 patients were prescribed an antiplatelet and an anticoagulant without gastroprotection[7]

. (see Figure). In the same quarter, there were 38 admissions to hospital for gastric bleeds for every 10,000 patients taking an NSAID and an anticoagulant, and 117 admissions for every 10,000 patients on an anticoagulant and an antiplatelet without gastroprotection.

Figure: Number of patients prescribed potentially risky anticoagulant combinations between 2015 and 2019

Source: NHS Business Services Authority Medication Safety Dashboard

These figures come from a series of prescribing indicators developed by the NHS medication safety programme in May 2018. The indicators link prescribing data with hospital admissions to help identify prescribing that could potentially increase the risk of harm to patients.

NICE and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency both say that special care should be taken when deciding to prescribe NSAIDs or antiplatelets with anticoagulants because they may increase the risk of major bleeding.

A 2018 study showed that concomitant oral anticoagulant and NSAID therapy in patients with AF increases the risk of major bleeding by 68% and the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) major bleeding by 81%. The combination also increases the risk of stroke by 50% and the risk of admission to hospital by 64%[8]

.

Anticoagulants and antiplatelets alone both increase the risk of upper and lower GI bleeding[9]

. Dual antiplatelet therapy approximately doubles the risk of bleeding compared with aspirin alone and the addition of an anticoagulant doubles that risk again[10]

.

Knight describes the numbers of people on these potentially harmful combinations as “worrying” but admits that she can see how some patients end up on them. She says many patients taking anticoagulants and NSAIDs are older people, have comorbidities, are potentially living with painful arthritis and may have been taking paracetamol for a long time.

When the patient’s pain increases, their doctor prescribes them an NSAID in order to improve their quality of life.

“GPs are just so overworked — when it comes to the point [of prescribing], they … just say ‘right let’s get this patient pain free and give them an NSAID’,” says Knight.

But Bhandal warns that once a patient is on an NSAID, it can be difficult to persuade them to stop taking it.

“[Switching to] two big [tablets of paracetamol] four times per day rather than one small [NSAID] in the morning [and] in the evening” will not be achievable for some patients, she says, adding that NSAIDs “keep them comfortable … until they have a bleed”.

GPs are feeling that there’s nowhere else to go with analgesics for patients and forget the basic rule that anticoagulants and NSAIDs are a no-go

She believes that educating patients about the risks of NSAID use in terms of kidney function and bleeding leads to some being more motivated to stop taking them.

Fay speculates that another reason for doctors continuing to prescribe NSAIDs alongside anticoagulants is because of “increasing scrutiny” on opioids and gabapentinoids.

“GPs are feeling that there’s nowhere else to go with analgesics for patients and forget the basic rule that anticoagulants and NSAIDs are a no-go.”

However, Russell argues that it is not always black and white when it comes to medicines that may potentially interact.

“[It’s about] weighing up risks and benefits. In training, you’re told you should never see aspirin and warfarin together but, in some situations, it’s less risky than someone getting a clot after a stent. It’s about having the background information and working out what’s appropriate for that patient — not one size fits all.”

In patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention, or who have acute coronary syndrome, valvular heart disease, deep vein thrombosis or a high risk for coronary events, an antiplatelet combined with an oral anticoagulant may provide benefit[11]

.

Sometimes, however, patients end up on anticoagulants and antiplatelets when they do not need to be. If there is any doubt about the ongoing need for a patient to take an antiplatelet with an anticoagulant, advice should be sought from local cardiologists, advises Bhandal.

Pharmacists in the care pathway

Clearly there are already good examples of how pharmacists have been supporting patients around anticoagulation, from initiation through to adherence, but there is more that needs to be done to raise awareness of the potential pharmacists could have in this area.

Anticoagulation UK is currently embarking on a project with community pharmacists and patients to develop individual anticoagulation care plans. The project will enable pharmacists to monitor patients taking anticoagulants, help optimise their care and ensure that they are adhering to their medicines. It will also help with continuity of care if patients are admitted to hospital.

“Every patient should have a care plan tailored to them — it should be in their notes [and] they should have a copy of it so everyone can see they are on an anticoagulant and can consider very carefully what they are giving them,” says Knight.

“In an ideal world — and we’re working to get some funding — we’d have an app that [patients] could download and they could [communicate with] the pharmacist by inputting what’s going on [with their medication].

“If it works then it could be a game changer,” she says. But in order to do this, pharmacists need support, both financially and educationally.

With the work of organisations and specialist pharmacists, such as Anticoagulation UK and Bhandal, it is clear that pÂharmacists can do a lot to improve patient safety when it comes to anticoagulants.

As the use of these drugs continues to rise, along with our ageing population, it is crucial that pharmacists are recognised and supported to improve the safety of patients taking anticoagulants, and to identify and review patients on potentially risky drug combinations as quickly as possible.

Box: New anticoagulation guidance for pharmacists

Earlier in 2019, the International Pharmacists for Anticoagulation Care Taskforce (iPACT) — a multidisciplinary network of experts from across 25 countries — launched an interprofessional guideline to help support patients receiving oral anticoagulants and improve their quality of life[12]

.

The guidelines were developed to complement international guidance already available.

“The international guidelines tend to have a focus around initiation [of anticoagulation] … but we know that that’s just part of the job, and we wanted to develop some guidelines that were multidisciplinary and [covered] the whole patient pathway,” says Sotiris Antoniou, consultant pharmacist in cardiovascular medicine at Barts Health NHS Trust, chair of iPACT and co-author of the guideline.

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Atrial fibrillation: management. Clinical guideline [CG180]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180 (accessed August 2019)

[2] Cowan C, Fay M & Maskrey N. The new NICE AF guideline and NOACs: a response. Br J Cardiol 2015;22:53–55. doi: 10.5837/bjc.2015.019

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Supporting local implementation of NICE guidance on use of the novel (non-vitamin K antagonist) oral anticoagulants in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180/resources/nic-consensus-statement-on-the-use-of-noacs-243733501 (accessed August 2019)

[4] Elliott RA, Camacho E, Campbell F et al. Policy Research Unit in Economic Evaluation of Health & Care Interventions. Prevalence and economic burden of medication errors in the NHS in England: Rapid evidence synthesis and economic analysis of the prevalence and burden of medication error in the UK. 2018. Available at: http://www.eepru.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/eepru-report-medication-error-feb-2018.pdf (accessed August 2019)

[5] NHS England & NHS Improvement. The NHS Patient Safety Strategy: Safer culture, safer systems, safer patients. 2019. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/5472/190708_Patient_Safety_Strategy_for_website_v4.pdf (accessed August 2019)

[6] Burn J & Pirmohamed M. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin: is new always better than the old? BMJ Open Heart 2018;5(1): e000712. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000712

[7] NHS Business Services Authority. Medication Safety Dashboard. 2018. Available at: https://apps.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/MOD/MedicationSafety/atlas.html (accessed August 2019)

[8] Kent AP, Brueckmann M, Fraessdorf M et al. Concomitant oral anticoagulant and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(3):255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.063

[9] Lanas A, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Arguedas Y et al. Risk of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015 13(5):906–912.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.007

[10] Beales I. The importance of gastrointestinal protection with dual antiplatelet therapies. BMJ 2017;358:j3237. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3237

[11] Floyd C & Ferro A. Indications for anticoagulant and antiplatelet combined therapy. BMJ 2017;359:j3782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3782

[12] Damen N, Van den Bemt B, Hersberger K et al. Creating an interprofessional guideline to support patients receiving oral anticoagulation therapy: a Delphi exercise. Int J Clin Pharm 2019;41(4):1012–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11096-019-00844-0