Mclean

“Rather than wait two weeks to see a GP, people can get immediate diagnosis, treatment and medication for the price of a Nando’s,” said Seb James, chief executive of Boots UK, in October 2021.

He was speaking to The Sun newspaper about plans for a new, private in-store “GP-style” prescribing service, with appointments apparently starting at £15.

Of course, you could argue that pharmacist independent prescribers are worth much more than some chicken and chips, but this recent announcement reveals a wider trend in pharmacies providing these services.

Leyla Hannbeck, chief executive of the Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies, says the number of pharmacies offering private services has increased “particularly in the last 18 months”, as members respond “to demand from within our local communities because some of these services are no longer available on the NHS, or it is no longer convenient to access the full range of GP services because face-to-face appointments are not always easily accessible”.

Simon Dukes, former chief executive officer of the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC), also candidly told The Pharmaceutical Journal in October 2021 that the sector could face even more funding cuts and that contractors should consider providing private services to make up the shortfall.

Online services

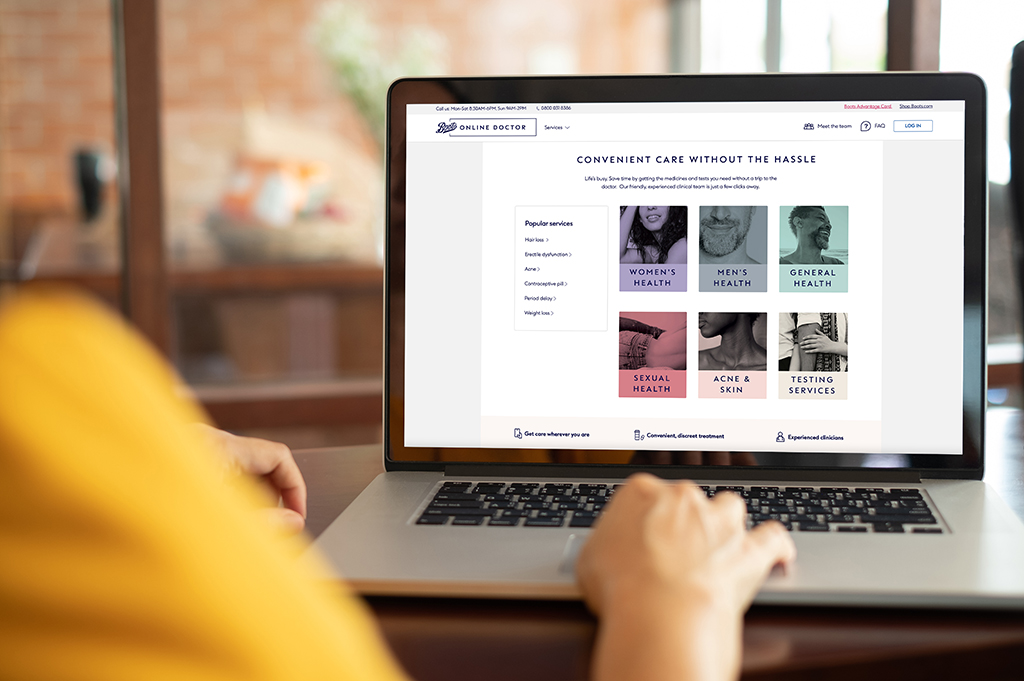

The multiples are stealing a march on this. In addition to its new in-store offering, Boots also expanded its ‘Online Doctor’ service in June 2021, with patients now able to access treatments for more than 30 conditions and 11 testing services.

These include services in which a team of pharmacist independent prescribers, nurse prescribers and GPs prescribe asthma inhalers for up to £158 for two inhalers, hormone replacement therapy at a cost of up to £150 (depending on the prescription) and adrenaline auto-injectors for up to £99 for two pens. The most expensive prescription offered costs £280 for five Saxenda 6mg/mL pens (Novo Nordisk) to aid weight loss.

Shutterstock / Boots UK / MAG

Despite the cost, ‘The Boots digital healthcare trends report 2021’ says the service has been steadily growing since its launch, having proved particularly popular among those aged 20–34 years, who make up more than half (60%) of all patients seen by the service.

LloydsPharmacy has had an ‘Online Doctor’ service since 2002 that prescribes for a variety of conditions, ranging in cost from £15 for one Ventolin (salbutamol; GSK) inhaler to £469 for three injections of HPV vaccine Gardasil 9. The costs are significantly marked up from their drug tariff prices — with the same Ventolin inhaler listed as costing £1.50, for example — but cover the consultation, medication and delivery.

A spokesperson for the multiple said its pharmacists “relish these opportunities to use a wider range of clinical skills in support of our patients and customers”, adding that LloydsPharmacy is “always developing our service to respond to patient needs”.

And this could be part of a wider trend towards the increasing use of private healthcare. In April 2021, market research company LaingBuisson predicted the private healthcare market will grow by 10–15% in the next three years as NHS waiting times increase post-pandemic.

First port of call

Marc Donovan, chief pharmacist at Boots, says the expansion of the multiple’s private service offering was to “become everyone’s first port of call for their health” and that Boots plans to provide a private mental health service by the end of 2021.

“We hope that by providing access to both NHS services and private healthcare on the high street or online, we can help to relieve pressure on our NHS,” he says.

Ade Williams, lead prescribing pharmacist at Bedminster Pharmacy in Bristol, prescribes a range of travel vaccinations and COVID-19 PCR travel services at prices he describes as “competitive”. He says his pharmacy began offering private services after the funding cuts in 2016.

“We informed our community about the tough choices we faced, including reducing our community health initiatives by 40% to help sustain some of our unfunded but vital work,” he says, adding that patients began suggesting private health services that were lacking locally, to help generate income “to keep our projects addressing health inequalities alive”.

Funding problems

Williams adds that, for him and his team, “there is a collective disappointment [around us having] had to go down this road, alongside coping with the slow pace and somewhat limited ambition of NHS-commissioned services” in England.

The irony is that we are creating private income streams to help us deliver the best NHS care possible

Ade Williams, lead prescribing pharmacist at Bedminster Pharmacy, Bristol

“There is a real sense that it is only by building the community pharmacy clinical offerings ourselves that we will be able to demonstrate the value of our expertise.

“The irony is [that we are] creating private income streams to help us deliver the best NHS care possible.”

And that is the driving factor here.

In the opening lines of the government’s contractual framework for community pharmacy in England, which began an overall five-year funding freeze in July 2019, former health secretary Matt Hancock made grand claims of community pharmacy being newly placed as “the first port of call for minor illness”.

However, three years into this contract, NHS-commissioned services have more firmly placed community pharmacy as a second port of call — reliant on referrals for minor illnesses, such as acne, hair loss and sleep difficulties, from NHS 111 or general practice through the community pharmacist consultation service (CPCS).

And it has not exactly been a money spinner. It had been expected to bring in around £4m in 2019/2020 and £9m in 2020/2021. But, so far, referral numbers from NHS 111 have been lower than planned and take-up of the GP referral service was hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic when it launched in November 2020.

Data published on 28 October 2021 by NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) show that community pharmacies earned just £1.9m through the CPCS in 2019/2020 and £5.3m in 2020/2021.

And with 7,361 pharmacies signed up to provide the service in 2019/2020 and 9,284 pharmacies signed up in 2020/2021, this only equates to approximately £271 and £572 per pharmacy in each of the years, respectively.

In response to the NHSBSA data, Alastair Buxton, director of NHS services at the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC), told The Pharmaceutical Journal that although referral volumes are now increasing, community pharmacies could better support the access challenges many patients are facing across the NHS if the number of referrals was “substantially increased”.

On 14 October 2021, NHS England published plans asking all GP practices to sign up to provide the CPCS by 1 December 2021, in an effort to increase the number of referrals to community pharmacy. However, medical unions are supporting GPs in boycotting the plans, because it fails to “reduce the unnecessary burden” on GPs, and it feels too little too late.

Community pharmacies are also facing unprecedented pressures, particularly financially, with data published in October 2021 revealing that England has the lowest number of community pharmacies in the past six years, after a record number of closures following the funding freeze.

Devolved nations

Despite the grim picture in England, NHS pharmacist prescribing schemes in other areas of the UK are thriving.

Under Scotland’s NHS ‘Pharmacy First’ scheme, which launched in July 2020, community pharmacists can offer free advice and prescribe treatments to patients presenting with a wide range of minor conditions. More than 2 million consultations have been carried out since its launch and it is expected to keep expanding.

In Wales, the NHS announced that all local health boards would be able to commission any community pharmacy to provide an independent prescribing service (IPS) from 1 November 2021. The service uses the pharmacist independent prescriber workforce to prescribe medicines for conditions such as hay fever, athlete’s foot and eye infections.

As of June 2021, Welsh pharmacies had carried out more than 16,000 IPS consultations during the service’s pilot phase — a number that could grow quickly under the government’s target for 30% of community pharmacies to employ an active independent prescriber by 2022.

With no such targets in England, providing private prescribing services is a way of offering opportunities to independent prescribers — an otherwise underused part of the profession — outside the NHS, because the NHS largely relies on local patient group directions (PGDs).

PGDs provide a legal framework to allow pharmacists to supply and administer certain agreed treatments to pre-defined groups of patients without a prescription or needing to be a prescriber. Each PGD is developed locally by multidisciplinary working groups and authorised by one of five types of organisations, including clinical commissioning groups and NHS England.

However, PGDs can also be bought by pharmacies from a range of suppliers to provide private services treating many conditions, such as impetigo, weight loss and acne.

Nobody should feel as though they are in a position where they have to pay for care and services that are available on the NHS

Martin Marshall, chair of the Royal College of GPs

Social goodwill

Not everyone is fully supportive of these private pharmacy services. Martin Marshall, chair of the Royal College of GPs, told The Pharmaceutical Journal: “This kind of paid-for GP service might be appropriate, convenient and within the means of some people, but nobody should feel as though they are in a position where they have to pay for care and services that are available on the NHS.

“GPs and our teams are working under intense workload and workforce pressures,” he says and has called on the government to introduce “measures to tackle ‘undoable’ workload in general practice — so that we can deliver the care and services our patients need”.

And with GPs providing 1.3 million consultations per day to their registered patients, it is unclear whether online private pharmacy services will make any significant contribution to improving patient access to healthcare.

Helga Mangion, policy manager at the National Pharmacy Association, insists that developing “integrated NHS services remains key to the sector’s future overall”.

Independent pharmacies are “responsive to local need and often provide a private service where there are gaps in NHS service commissioning,” she says.

“However, there are fewer private options for pharmacies in deprived areas and it is important that NHS provision is comprehensive and meets the needs of all communities.”

And Williams describes the dilemma of choosing to provide private services to make up for the NHS’s shortcomings as a “moral crisis for many of us trying to map our way to a sustainable footing”.

He fears that by providing private services, “in the long run, we are decoupling the unique social goodwill that sets community pharmacies apart”.

However, the winds of change are clearly blowing in the opposite direction.

Contractor view: ‘We see this as a critical offer to support the NHS’

David Evans, chief pharmacist and managing director at Daleacre Healthcare, which owns 12 Evans Pharmacy branches across Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, says his pharmacies provide travel and lifestyle medicines privately “from an independent prescribing perspective rather than from a patient group direction (PGD)”.

The service was set up “because the NHS won’t commission us to actually use our prescribing qualifications, so we have to use them ourselves” he says, adding that, while his pharmacies began offering private services for “professional satisfaction”, the additional money through the service “obviously helps”.

Pete Horrocks, superintendent pharmacist at Knights Pharmacy, says his small chain of 90 pharmacies across the country employs “a number of prescribers” but currently offers private services, such as weight management and vaccination clinics, through PGDs.

“We do expect this to change over the coming years and see this as a critical offer to support the NHS by offering alternative points of care for patients,” he says.

“We are particularly excited to work with local NHS organisations to offer prescriber-led clinics that are commissioned locally and create additional capacity in local systems.”