Shutterstock.com

Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/coronavirus

Rani Khatib had a demanding job as a consultant cardiology pharmacist at Leeds General Infirmary when he contracted COVID-19 in November 2020.

After developing a headache, cough and fever, he tested positive for the virus, meaning that he and his household were forced to isolate in their home near Halifax, West Yorkshire. Khatib, who is in his 40s, continued what he could of his busy work schedule, delivering an online lecture to a national cardiology meeting. “Everybody noticed, of course, I was just talking, talking, talking and then coughing,” he says.

When Khatib’s oxygen saturations dropped dangerously low (he had an oximeter at home), he called for an ambulance, but he remained upbeat. “Being young, I have no risk factors as such … I’m otherwise fit and well,” he says. “I thought this will probably be a couple of weeks of oxygen, worst-case scenario, and I’ll be fine.”

However, Khatib was admitted to hospital, eventually put into an induced coma and ventilated for two months. Nine months later, he is still suffering symptoms — exhaustion, peripheral neuropathy, a persistent dry cough — and has yet to return to work.

“When I first came home, I could barely complete a sentence. I was out of breath,” he says.

Khatib’s symptoms are recognised as part of a phenomenon known as ‘long COVID’ or ‘post-COVID-19 syndrome’, where signs and symptoms persist for more than 12 weeks after a COVID-19 infection. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence describes the symptoms as highly variable and wide ranging[1]. Multiple systems can be affected: respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and psychological.

According to data from the ‘REACT long COVID’ (REACT-LC) study, led by researchers at Imperial College London, up to one in three people who have had COVID-19 report symptoms of long COVID (see Box 1)[2].

Khatib is one of a growing number of pharmacy professionals experiencing ongoing symptoms; often young, previously fit and healthy, individuals left with debilitating symptoms that are changing their lives and threatening their careers.

Box 1: Prevalence of long COVID

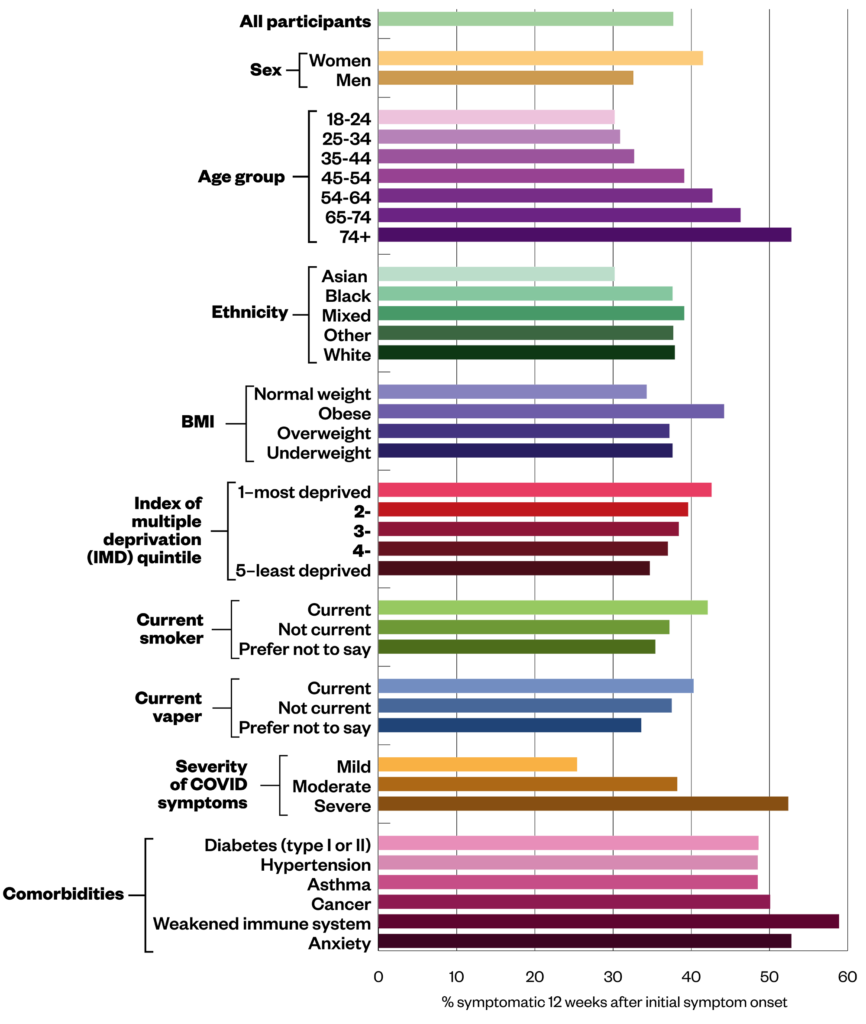

Estimates for the prevalence of long COVID vary. Data from the REACT-LC study released in June 2021 suggest that, in England, more than 2 million people are living with self-reported COVID symptoms that have lasted for 12 weeks or longer. Data from the study also show that the prevalence of long COVID increases with age and is higher among women (see Figure 1).

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) puts the UK figure for long COVID at around 850,000 (1.32% of the population), with the most common symptoms being fatigue, shortness of breath, muscle ache and difficulty concentrating.

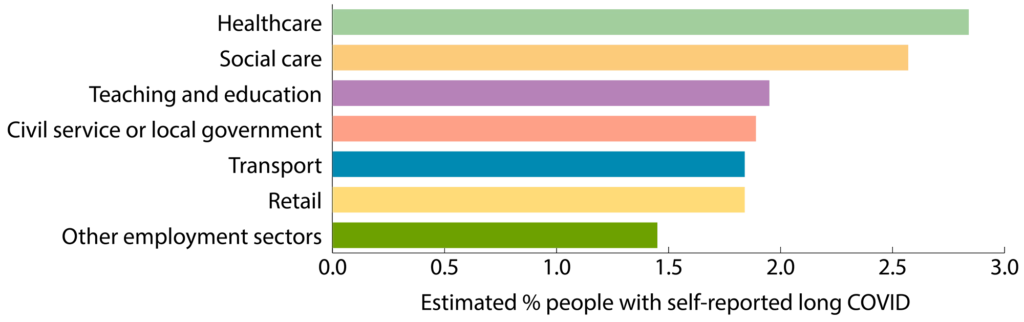

ONS data also show healthcare workers as having the highest prevalence rates of self-reported long COVID (see Figure 2). Data on the prevalence of long COVID among pharmacists are lacking.

Pain and exhaustion

Ana Wright* qualified as a pharmacist in 2019, just months before the COVID-19 pandemic struck. In April 2020, while working at a district general hospital in North West England, she developed severe muscle aches — not a recognised symptom of COVID-19 at the time. “Nothing was relieving it, nothing was making it go away,” she says. Wright, who is now aged 26 years, felt constantly exhausted.

At the time of the onset of her symptoms, testing for NHS staff with atypical symptoms was not available, so Wright continued to work, not wanting to let her colleagues down.

“It was really, really tough,” she says, describing days at work when she would struggle to cover her wards because of the distances involved. “I’ve done all three levels of my [Duke of Edinburgh awards]. I’ve done much worse in terms of physical [exertion].”

Over a year later, Wright still suffers with muscle pain and her liver function profile continues to show high creatine kinase levels, indicating muscle breakdown. Wright says her GP has been supportive and has diagnosed her with long COVID., but she feels let down by her employer. She says she was asked to reconsider taking up a sick note when her symptoms were at their worst because the hospital was understaffed and overstretched.

There were so many things that should have been done differently; being able to sit at home and rest and think ‘I shouldn’t feel guilty’

Ana Wright*, pharmacist at a district general hospital

“There were so many things that should have been done [differently],” she says. “Being able to take that time [off], being able to sit at home and rest and think ‘I shouldn’t feel guilty’.”

Lucy Holt* — a 31-year-old critical care pharmacist at a rural district general hospital — was an active runner before contracting COVID-19 in spring 2020. “It’s been a massive change,” she says. “I haven’t tried running in over a year. Walking is my limit now.”

Holt was forced to isolate in April 2020 after her partner, a doctor, fell ill with COVID-19. Holt initially worked remotely, before developing symptoms herself. “I was the only critical care pharmacist [working] for the trust at that time,” she says. “I was frantically trying to do work from home.”

After two weeks at home, she returned to work but didn’t make it through the day. “I was sent home after about two hours, had another week off and then when I did go back to work, I was absolutely exhausted.”

Some days, it was like my brain was full of treacle, and it was really hard to think properly

Lucy Holt*, critical care pharmacist at a rural district general hospital

May and June 2020 were tough, says Holt, but as the first COVID-19 wave slowed, things got easier. “I was coping OK, but I kept having to have days off [as annual leave].” By November 2020, any progress Holt had made during the summer was lost. “I was struggling to get through a day without feeling terrible,” she says. “Some days, [it was] like my brain was full of treacle, and it was really hard to think properly.”

Holt eventually saw her GP but her blood results came back normal. Her options were limited. “The only thing they said they could do was sign me off,” she recalls. But Holt wanted to keep working.

Similarly, Geraint Jones, advanced pharmacist specialising in HIV and homecare at Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board in Wales, and Karen Cook, a clinical services manager for a private hospital chain in England, have also experienced massive changes in their physical capabilities.

Before contracting COVID-19 in April 2020, 31-year-old Jones was a keen footballer and played weekly five-a-side. He was also using the gym four or five times per week and doing high-intensity training with a coach at Cardiff City Football Club. “Now, I walk the dog for 20 minutes, I’m absolutely knackered,” he says.

Cook, who is in her 50s, used to be a Zumba fanatic. “I’ve been going for years,” she says. “That’s my love, Zumba music and dancing.” However, the high-energy exercise class came to an end when she fell ill in March 2020; now Cook gets her exercise by taking gentle strolls.

Like Holt, Jones continued to work through the summer of 2020. Sometimes, because of his gastrointestinal symptoms, he worked from the bathroom at his home, “… nine, ten hours a day, ringing patients, organising prescriptions, signing things off”. This was clearly unsustainable and he was forced to take sick leave as his symptoms worsened. Jones has been off work since September 2020.

Concentration and memory issues

When Cook contemplated returning to work, memory issues were her biggest concern. “As a pharmacist … you really do need to be spot on … and the thought of drug interactions and complicated questions [worried me].”

Her brain fog is better, which Cook puts down to the anticoagulation therapy she started after being diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome and multiple blood clots. But her memory problems continue. “Being back on site a few hours a day has highlighted how much I still cannot remember.”

Cognitive issues have also plagued 47-year-old David Barnard, a senior oncology pharmacy technician at Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Trust, London, who — seven months after a positive COVID-19 test in December 2020 — admits that he has made “rookie errors” at work because of his concentration issues.

“The errors at work have significantly knocked my confidence and I worry about making a serious error,” he says.

Jones says there have been days when he couldn’t string a sentence together. “My health board asked me to do a video about long COVID to highlight the problems I’d had … it was taking weeks,” he recalls. Jones wanted to use the video to express gratitude to his colleagues but couldn’t think of the right word. “I just burst into tears … because I couldn’t think how to say thank you,” he says.

Barnard feels well supported by his employer but he is conscious that there are limited options for occupational adjustments to manage his ongoing memory and concentration issues. “No amount of aide memoirs or checklists are helping,” he says.

“I would like to see organisations helped with how to support staff suffering from [these] issues, as it is harder to adjust to compared with a physical issue.”

Jones has spent around £3,000 on private consultations and investigations to try to understand his symptoms, which have included chronic diarrhoea, gastrointestinal pain, unilateral tinnitus, heart palpitations and exhaustion. “Some days it feels as if my stomach is on fire. I’ve got no doubt that there’s viral persistence or inflammation there,” he says.

The tests, scans and consultations have revealed a variety of conditions, including myocarditis, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, lung scarring and reduced lung capacity. A colonoscopy showed that Jones’ bowel was in spasm.

Alongside long COVID and antiphospholipid syndrome, Cook has been diagnosed with pericarditis — she is under the care of a cardiologist, rheumatologist and haematologist. She is convinced that her diagnoses came because, as a pharmacist, she knew the right people and the right questions to ask.

“I used all the networks that I know from my job, and all my contacts,” she says (see Box 2).

Box 2: Where to seek help

The NHS has opened 81 long COVID assessment clinics across England and invested more than £50m in research to help improve understanding of the condition, from diagnosis and treatment to rehabilitation and recovery. In Scotland and Wales, long COVID is primarily being managed in primary care through GPs. However, access to help has been patchy.

Geraint Jones, advanced pharmacist specialising in HIV and homecare at Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board in Wales, is frustrated by the lack of a clear pathway for managing long COVID and has struggled to access services in Wales.

In Yorkshire, Rani Khatib — a consultant cardiology pharmacist at Leeds General Infirmary — is waiting for a clinic dedicated to long COVID to be set up in his local area. In the meantime, he has received physiotherapy support through the local pulmonary rehabilitation team, as well as a 12-week COVID-19 rehabilitation programme provided through the charity arm of Nuffield Health.

Meanwhile, a clinical psychologist has been seconded to the intensive therapy unit and respiratory department at the rural district general hospital where Lucy Holt* works as a critical care pharmacist to help staff deal with the trauma of working through a pandemic, including the effects of long COVID.

Karen Cook, a clinical services manager for a private hospital chain, has found support from others with long COVID through Facebook groups, some of which have swelled to tens of thousands of members. She says other professional groups, such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists, have developed effective long COVID support networks. She would like to see something similar for pharmacists.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society is developing support alerts, blogs and professional guidance relating to long COVID, and has a support line available for one-to-one discussion and support. It has also hosted a long COVID webinar (see Box 3).

Employment support and return to work

The Pharmacists’ Defence Association (PDA), which aims to assist and support individual pharmacists and pharmacy students, is advising its members who believe they contracted COVID through exposure at work to ask their employer if a RIDDOR (Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013) report has been made to the Health and Safety Executive.

Employers are legally obliged to record workplace exposure to COVID under RIDDOR and, where employers dispute the need to report, employees may be able to put in a grievance.

“You’ve [then] at least got a contemporaneous record,” says Paul Day, director of the PDA, who points out that long COVID might mean the end of a pharmacist’s career or that they are not able to cover their normal shifts. “We just don’t know what the long-term consequences will be,” he adds.

David Strain, a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, participated in the ‘NHS long COVID taskforce’, which was put together to inform the NHS’ approach to long COVID and comprises NHS staff and researchers, as well as people with lived experience of long COVID. He believes hospital workers affected by long COVID have generally been well supported.

“We’ve got lots of people who are on phased returns, even six or seven months later.” By adopting a ‘pacing’ approach, returning employees are offered the opportunity to work shorter shifts and take allocated rest time, he says.

However, Holt points out that the system is not designed to support those who want to continue working but who need to reduce their hours — phased return is generally only an option after extended sick leave. “You can either go off sick, or you can reduce your hours and get paid less, there is no middle ground,” she says.

As she struggled with work through the spring of 2021, Holt and her line manager came up with a flexible working plan, whereby Holt could work partly at the hospital, partly from home. “We tried to work with [occupational] health but they kept delaying my appointment,” she says. “After [they] had delayed me for the fourth time, I gave up — and said, ‘I’m going off, I can’t keep going’. So, I was signed off by my GP.”

Jones says that while he really wants to get back to work, he has had to put his professional development — such as training as an independent prescriber — on hold. “I found that when I was giving myself goals, I couldn’t reach them, and then it just drives your mental state into the ground,” he says.

Cook suspects that many individuals with long COVID do not feel valued in the way they did previously. “When you start putting your hand up and saying ‘I can’t do all that’, you sound a bit pathetic,” she says. “I try really hard not to let it show. But, sometimes … I feel so sad that I can’t be who I used to be.”

When Cook tried to return to work in October 2020, she was overwhelmed by the noisy environment and found walking around the hospital hard. Instead, she was redeployed to a project that allowed her to work from home, at her own pace.

After three months on sick leave, Barnard says he felt compelled to return to work. “Not due to any pressure from work but a real concern that I would never get better and, somehow, I had to re-adjust my life to … manage,” he says. “Providing financial support for my family became a real worry.”

Khatib is starting to think about returning to work but will take things slowly, with a phased return. He will need to consider practical challenges, such as where he will park. “Previously, … I could park anywhere [and walk in],” he says.

Adding to this difficulty, Khatib’s peripheral neuropathy makes it uncomfortable to stand for any period of time. “If I stand on my feet for a few minutes, it’s like they’re on fire,” he says.

For these reasons, Khatib expects remote working to form part of his return-to-work plans. “I can contribute virtually,” he says. “The physical aspect will take longer.”

Cook, too, expects remote working to feature in her plans. “The expectation is you’re back in your role, so you’re fine,” she says. “[But] I’m finding it very hard to be on the premises, concentrating all the time in the environment, with the dryness and the mask. … I need to prove that I can do some of it at home.”

Khatib says that COVID-19 has given him a wake-up call, causing him to reconsider how he approaches life and the demands of his job. “[I was] on the run all the time, running from this to that,” he recalls. “But you have a family, you have a life to live, to look after them. So, I’ll probably be rethinking.”

*Not pharmacists’ real names

Box 3: Resources

Long COVID clinics and self-management:

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Health Improvement Scotland, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and Royal College of GPs. Long COVID: a booklet for people who have signs and symptoms that continue or develop after acute COVID-19: https://www.sign.ac.uk/patient-and-public-involvement/patient-publications/long-covid/

Nuffield Health. COVID-19 rehabilitation programme: https://www.nuffieldhealth.com/about-us/our-impact/healthy-life/covid-19-rehabilitation-programme

NHS. Your COVID recovery: https://www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk/

World Health Organization. Support for rehabilitation: self-management after COVID-19 related illness: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/support-for-rehabilitation-self-management-after-covid-19-related-illness

Long COVID webinars:

All Party Parliamentary Group on Coronavirus: https://youtu.be/UXakeS4Edac

All Party Parliamentary Group on Coronavirus: https://youtu.be/XK5Jz4Yqr8A

Royal Pharmaceutical Society: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/webinars/long-covid-what-is-it-and-how-to-manage-it

Long COVID support groups:

Long COVID SOS: https://www.longcovidsos.org/

Long COVID Support: https://www.longcovid.org/

Long COVID Scotland: https://www.longcovid.scot/

Long COVID Wales: https://www.facebook.com/groups/longcovidwales

Long COVID Support Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/longcovid

COVID-19 Recovery: https://covid19-recovery.org/

COVID-19 Long Haulers Support: https://www.facebook.com/groups/373920943948661

Advice for employers and employees:

The NHS Staff Council. Management of long-term COVID-19 sickness absences: https://www.nhsemployers.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/Long-term-covid-absence-guidance.pdf

Health and Safety Executive. RIDDOR reporting of COVID-19: https://www.hse.gov.uk/coronavirus/riddor/index.htm

NHS Employers. Supporting recovery after long COVID: https://www.nhsemployers.org/articles/supporting-recovery-after-long-covid

Acas. Long COVID – advice for employers and employees: https://www.acas.org.uk/long-covid

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. Long COVID: https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/coronavirus/long-covid

- This article was amended on 13 August 2021 to reflect that David Strain is no longer co-chair of the British Medical Association’s medical academic staff committee

- 1National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. NICE guideline NG188. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed Aug 2021).

- 2Whitaker M, Elliott J, Chadeau-Hyam M, et al. Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a random community sample of 508,707 people. Imperial College London 2021. https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/89844 (accessed Aug 2021).