Iratxe López de Munain

Parosmia. You’ve probably never heard of it. I hadn’t. Not, that is, until my 13-year-old daughter developed the condition after a mild bout of COVID-19 in September 2021.

Although most people will now be familiar with, or may even have experienced, loss of smell — known as anosmia — during an acute COVID-19 infection, they may not be aware of parosmia — a lesser-known smell disorder.

For my daughter Zara, it started with a Saturday night takeaway, about two months after her initial COVID-19 infection (from which she appeared to have completely recovered). She gagged at the first mouthful, saying the chicken tasted off.

Over the next few weeks, more and more foods took on this same “COVID taste”. And things began to smell bad to her too; first, it was food, then it spread to shower gel, shampoo and even toothpaste. Now, five months on, it’s a stench that constantly lurks in our house, in the dining hall at school and even on seaside walks, and Zara is down to only a handful of what those living with the condition call “safe foods”.

Upturn in cases

It is thought that parosmia — a medical term that describes smell distortions that are often unpleasant — usually happens as people start to recover from the damage that has caused smell loss. For most, including Zara, the distortions seem to hit several months after the initial anosmia, and their duration can range from a few weeks to several months or even years; Cara Roberts, for example, is 16 months into her parosmia journey after contracting COVID-19 in December 2020.

Every smell that I knew, and every taste that I knew, had completely gone — and I didn’t know whether I was ever going to get them back

Cara Roberts, who lives with parosmia

“I woke up one morning and I felt like my whole world had changed,” explains 33-year-old Roberts, who lives in the north west of England and works as a regional manager for a student accommodation company. “Every smell that I knew, and every taste that I knew, had completely gone. And I didn’t know whether I was ever going to get them back.”

Before the pandemic, anosmia was believed to affect approximately 6% of the general population, with a higher prevalence in those aged over 60 years[1].

But COVID-19 has caused case numbers to rise dramatically.

“We know that viruses cause smell loss and have done for decades,” explains Carl Philpott, a rhinologist and consultant ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon, who set up Britain’s first taste and smell clinic back in 2010. “One of the most common presentations in my clinic was viral smell loss, before COVID-19 came along, but it’s just the sheer scale of it with COVID-19 that has made it so dramatic and turned the spotlight on it in quite a way that we haven’t seen possible before.”

It is estimated that about two-thirds of patients experience loss of smell during acute COVID-19 and about 10–15% of these report persistent symptoms for more than four weeks[2]. If you multiply this by the number of cases we have seen so far in the UK, it suggests that upwards of 2 million people might have suffered persistent smell loss following COVID-19, and a staggering 48 million worldwide. Around half of these will subsequently develop parosmia[3]. A caveat to these figures, however, is that there are some indications that the Omicron variant is causing less olfactory dysfunction, cautions Philpott.

This rise in olfactory disorders is reflected in the increasing numbers of people seeking support from charities, such as Fifth Sense and AbScent, which provide advice for those living with smell and taste disorders (see Box).

Box: Top tips for managing parosmia

- Remember, for most people, parosmia is a phase that will pass;

- Eat foods that are cold or room temperature since these will give off less odour;

- Keep a diary to establish changes, triggers and foods that are safe for you;

- Avoid obvious triggers. Some of the most common are coffee, toast, roasted or fried meats, deep fried foods, eggs, garlic, onions (raw or cooked), mint toothpaste and chocolate;

- Some people find that bland foods, such as rice, boiled potatoes and pasta, are palatable for them;

- Try a wide variety of foods. Something that tasted awful last week may not now;

- Try masking foods affected with a strong flavour that does not cause a distortion — for example, cinnamon, chilli oil or peppercorn sauce;

- If you cannot eat anything, try unflavoured or vanilla protein shakes;

- Use unscented toiletries and try cinnamon or herbal toothpaste if mint is triggering;

- For some people, wearing a padded nose clip when eating can help eliminate or reduce distortions.

Sources: Fifth Sense, AbScent

“Our membership has increased significantly since the pandemic began,” says Duncan Boak, the recently appointed chief executive of Fifth Sense, which he founded in partnership with Philpott in 2012 after suffering smell loss following a head injury.

AbScent had its official launch on 27 February 2020 — anosmia awareness day — just as the pandemic hit. “On the day of the launch, AbScent had 1,500 people in its Facebook group. Right now, we serve over 80,000 people on multiple platforms,” explains Chrissi Kelly, the chief executive officer of the charity.

The sense of smell has traditionally been perceived as the least important of our senses

Duncan Boak, chief executive of Fifth Sense

Despite this huge increase in the number of people affected, awareness of parosmia, and how these smell distortions can have such a huge impact on people’s mental health and quality of life — both among the public and healthcare professionals — is still low. And research into treatments for olfactory dysfunction has long been neglected.

“The sense of smell has traditionally been perceived as the least important of our senses … and that’s why smell and taste science and research has traditionally been undervalued, under done and underfunded,” explains Boak.

“Unfortunately, it’s taken a virus to come along that has meant that significant numbers of people across the world have experienced [smell loss] … for the world to wake up and go, ‘actually, this matters’.”

Normal life on hold

Part of the problem is that people with parosmia often find it hard to describe their symptoms, making it difficult for those around them to relate to the experience.

“It’s not like any food I have ever smelt or tasted before,” explains Zara. “All meat tastes the same, like it is out of date by at least a decade and has been sat in a rotting heap of compost for that whole time.

“Dairy tastes sort of like when you’ve left a piece of cheese out in the sun for a few days and it’s gone all sweaty and mouldy,” she adds, and carbohydrates tend to have a burnt cardboard-like smell.

And what tastes good and bad can vary from day to day, and even from hour to hour. This bizarre narrative can foster disbelief among non-sufferers.

In the beginning, Roberts couldn’t eat or drink anything without feeling nauseous, and lost so much weight that she ended up spending two weeks in hospital. But she wasn’t admitted to an ENT ward as you might expect. “They actually put me on an eating disorder ward because they didn’t believe me that parosmia was a thing.”

Roberts says that living with parosmia is like nothing she has ever had to deal with and has taken a huge toll on her mental health. “I lost two and a half stone in the course of three weeks. I couldn’t go to work because I could not be around smells like coffee to start with. I couldn’t go near my partner because I couldn’t stand the smell of him. I couldn’t be a mum because I couldn’t cook food for my little one.”

“Parosmia really affects all areas of your life,” adds Kelly, who founded AbScent after suffering from both anosmia and parosmia herself. “It is considered an ENT problem. But people need mental health support, they need dietary advice.”

Kelly and a team of researchers conducted a thematic analysis of user-generated text from 9,000 members of a moderated AbScent Facebook group and found that COVID-19-related sensory upheaval had “serious implications for food, eating, health, work and wellbeing and for some is a profound existential assault disturbing their relationship to self, others and the world”[4].

A lack of understanding and empathy from family, friends, colleagues and healthcare professionals was frustratingly common.

The nose knows

To understand parosmia, it is important to know how our noses work.

The average person can detect at least 1 trillion different smells. The lining of the roof of the nose, called the olfactory epithelium, is filled with millions of sensory nerves, the tips of which contain smell receptors — with about 12 million in humans. These receptors control our ability to smell; there are hundreds of different types that respond to different odours. The odour molecules bind with the receptors and this generates a signal that passes along the nerve fibres up to the olfactory bulb, a structure on the frontal lobe of the brain. The olfactory bulb then processes these signals and passes the information to other parts of the brain (see Figure; a downloadable version can be found here).

Each receptor can be activated by many different odour molecules, and each odour molecule can activate several different types of receptors. What we think of as a single smell is actually a combination of many odour molecules acting on a variety of receptors, creating a complex neural code that we can identify as a particular scent. Odours released when we chew foods or sip drinks combine with the basic tastes from the tongue (salt, sweet, sour, bitter, umami) to create the unified experience of flavour. Loss or distortion of smell leads to loss or distortion of our perceptions of flavour, commonly described as taste.

Philpott explains that there is ongoing debate about the full pathophysiology of parosmia, and several mechanisms could be involved. “We think it’s mostly a peripheral problem (i.e. at the receptor level at the top of the nose) but there are some theories around the fact that there’s a modification to that, that happens in the brain.”

We think it’s mostly a peripheral problem (i.e. at the receptor level at the top of the nose) but there are some theories that there’s a modification that happens in the brain

Carl Philpott, rhinologist and consultant ear, nose and throat surgeon

The theory for smell loss caused by COVID-19 infection is that the virus enters and kills sustentacular cells in the olfactory epithelium that support and nourish olfactory receptor neurones. This can lead to a malfunction of the neurones, temporarily causing anosmia.

If larger areas of sustentacular cells are affected, this could lead to damage to the neurons and hence longer-lasting symptoms.

The good news is that both sustentacular cells and olfactory receptor neurones can regenerate from stem cells within the lining of the nose — sustentacular cells much more rapidly than neurones. When the olfactory nerves start to recover from the initial damage, some receptors begin to work before others.

For example, the smell of a rose has 13 odour molecules, explains Philpott. “But if you can only pick out 6 of the 13 molecules, then you get some information, but you are missing some of the key bits that enable you to recognise what it is.”

“For some reason, those distortions tend to be unpleasant in nature. And I don’t think we quite understand why that is.”

This theory may not give the whole answer — the signal for the smell may be modified further centrally, and some have suggested that, as olfactory neurones regrow, there is incorrect rewiring. A recent UK Biobank study, published in Nature, investigated brain changes via two MRI scans before and after mild COVID-19 infection, and revealed tissue damage and greater shrinkage in brain areas related to smell[5]. It is not known whether this damage is a result of the effects of SARS-CoV-2 or the loss of sensory input owing to anosmia. It is also unknown whether these effects will persist in the long term.

Sniffing out answers

The many unknowns surrounding parosmia extend to its treatment too.

There is evidence that a technique called smell training can help to speed up recovery in some people with smell dysfunction, although it is by no means the answer for everyone.

The first evidence for smell training in olfactory disorders came from Thomas Hummel, who runs a smell and taste clinic at the University of Dresden, Germany. In 2009, he ran a study to investigate whether repeated short-term exposure to odours over several months would have any effect on the olfactory ability of 56 anosmia sufferers[6]. The smell training group involved 40 participants, who were given four essential oils — rose, eucalyptus, clove and lemon — and told to sniff each one each day, morning and evening, for 10 seconds at a time for 12 weeks. The other group did not participate in smell training. Hummel found that 28% of patients who had undergone the training experienced some improvement in olfactory function, compared with 6% in the group who had not participated.

In 2015, Hummel published a further study that suggested some additional benefit from smell training using a wider range of odours over a longer period[7]. Since then, three meta-analyses and several prospective controlled studies have suggested improved olfactory function with smell training[2].

Adding to this evidence, Hummel and colleagues, including Philpott, published a retrospective cohort study of 153 participants with post-infectious olfactory dysfunction in 2020, which focused specifically on whether those with parosmia could benefit from smell training[8]. They found that clinically relevant recovery of the ability to identify and discriminate between smells after smell training for up to nine months was more likely in those who had parosmia at the initial clinic visit.

It is thought that smell training works by increasing growth of olfactory receptor neurons and expression of olfactory receptors, although this is unproven. It has also been suggested that smell training may effectively improve cognitive processing of incomplete sensory information.

Philpott, who is also professor of rhinology and olfactology at the University of East Anglia, hopes to do a COVID-19-specific study on smell training. He has also applied for several grants to study other potential treatments for smell disorders. He already has funding for a proof-of-concept study on whether vitamin A nasal drops can help people to regain their sense of smell after viral infections, including COVID-19. Entitled the APOLLO study, it will involve 57 participants[9].

“Vitamin A drops are thought to help regenerate smell receptor activity,” explains Philpott.

Vitamin A drops are thought to help regenerate smell receptor activity

Carl Philpott, rhinologist and consultant ear, nose and throat surgeon

Participants will have an MRI scan before and after treatment. “While [participants are] in the scanner, they’ll be receiving smells through a dedicated olfactometer so that we’ll be able to get a measure of brain activity and look for any changes between the two scans.

“We hope to then move on to look at intra-nasal theophylline and intra-nasal sodium citrate, as they seem the most promising therapeutic agents.”

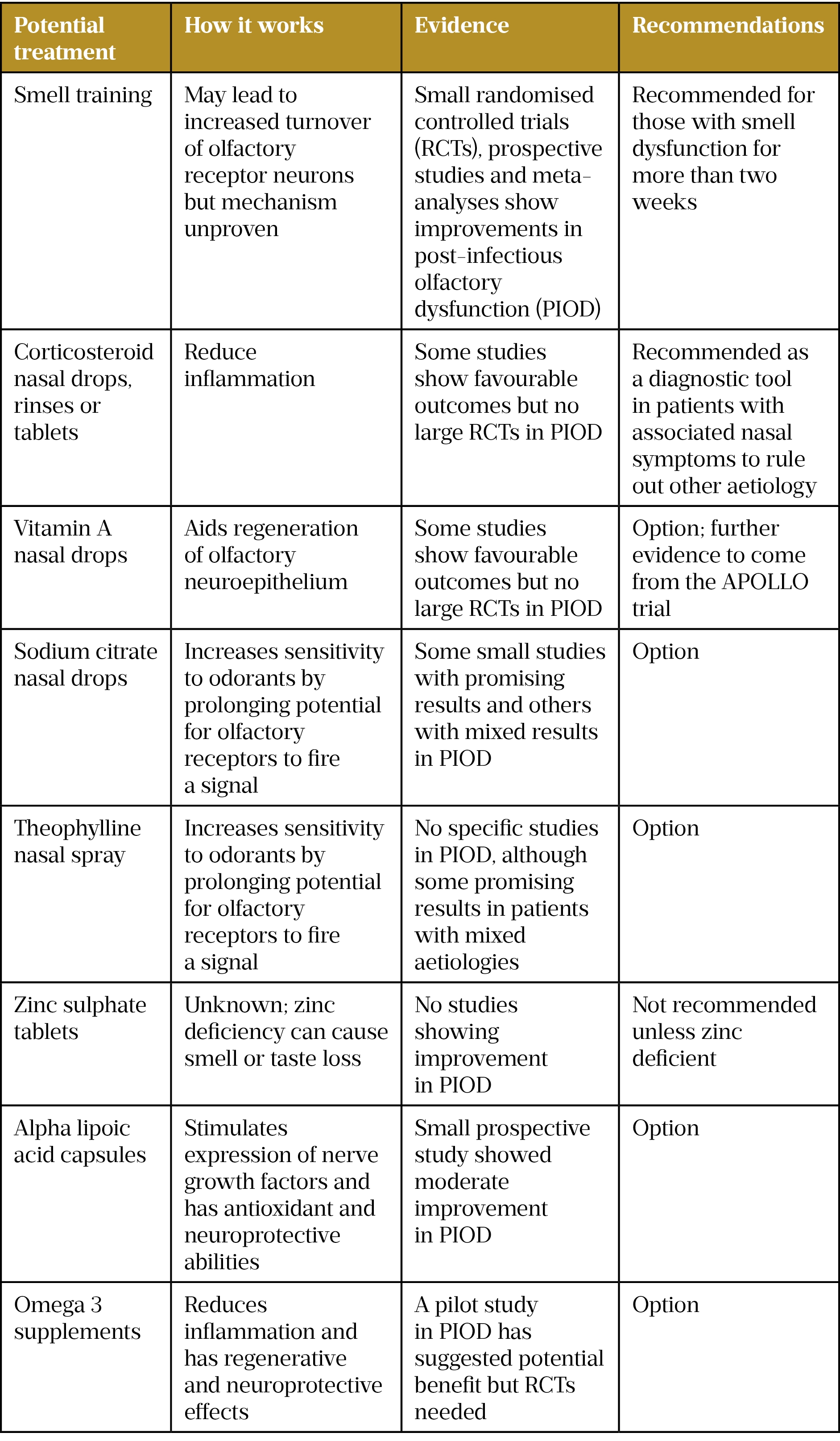

There are several other possible treatments but robust evidence for their effectiveness in post-infectious olfactory dysfunction is lacking (see Table).

Sources: Philpott C; Clinical Otolaryngology 2021;46:16; Rhinitis, Sinusitis and Ocular Allergy 2021;147(5):1704; Rhinology 2022;1;60(2):139

These treatments are often discussed within online support groups, as well as many others — some scientifically plausible and some not — for example, burning an orange on the stove, mixing it with brown sugar and eating it.

What the patient community desperately needs is evidence from gold standard randomised controlled trials. And that is something that Philpott and others within the specialty are trying to address.

Running with it

“I’ve been working hard in the past year or so to try to capitalise on [the spotlight COVID-19 has placed on olfactory disorders] by putting in funding applications to say, look, this is now a much bigger problem than it was before,” says Philpott. “Hopefully, by six months’ time, I might have quite a few more research grants to my name.”

Over the past few years, Fifth Sense has been engaging with people affected by smell and taste disorders, along with their families and clinicians, to capture unanswered questions and turn these into a set of research priorities. These priorities cover a range of areas, including education of medical professionals, mental health aspects of smell and taste impairment and, perhaps unsurprisingly, viral infections, including COVID-19.

“The charity’s new research hub has been established to take forward these priorities and drive research that will deliver impact for the people it represents across a number of strands, including clinical trials and epidemiology, education and training, and technology and digital health,” explains Boak.

Fifth Sense, Philpott and Kelly are all members of the Global Consortium of Chemosensory Research (GCCR), an international group of scientists, clinicians and patient advocates across more than 60 countries that came together in March 2020 to better understand the connection between loss of smell and taste and COVID-19.

The GCCR’s mission is to advance scientific understanding and clinical practice by encouraging and facilitating global collaboration on research into COVID-19 and olfactory disorders.

Kelly believes that COVID-19 has ushered in a new dawn for people with smell disorders. “It’s a new age for smell loss . . . this has really moved on the whole picture.”

Boak is also feeling positive about the future. “I think things could really start to shift this year,” he says.

This is good news for those with smell and taste disorders; effective treatments cannot come soon enough. Although Zara is learning to live with parosmia, the lack of nutrition, as well as the impact on her mental health from restricted eating, are a constant worry for me as her mother.

Roberts is encouraged by the renewed focus on research but is realistic about how long a breakthrough could take. “Obviously, the biggest thing that anybody would like is a cure. That’s probably not going to happen without a lot more research.

“Until there is that cure, there’s got to be that understanding piece, and there’s got to be some tools to be able to manage parosmia.

“Had I had that [in the beginning], I would have dealt with it a lot differently.”

- 1Brämerson A, Johansson L, Ek L, et al. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction: the skövde population-based study. Laryngoscope 2004;114:733–7. doi:10.1097/00005537-200404000-00026

- 2Addison AB, Wong B, Ahmed T, et al. Clinical Olfactory Working Group consensus statement on the treatment of postinfectious olfactory dysfunction. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2021;147:1704–19. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.641

- 3Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG, Green T, et al. Increasing incidence of parosmia and phantosmia in patients recovering from COVID-19 smell loss. 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.08.28.21262763

- 4Burges Watson DL, Campbell M, Hopkins C, et al. Altered smell and taste: Anosmia, parosmia and the impact of long Covid-19. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0256998. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256998

- 5Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5

- 6Hummel T, Rissom K, Reden J, et al. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss. The Laryngoscope. 2009;119:496–9. doi:10.1002/lary.20101

- 7Altundag A, Cayonu M, Kayabasoglu G, et al. Modified olfactory training in patients with postinfectious olfactory loss. The Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1763–6. doi:10.1002/lary.25245

- 8Liu DT, Sabha M, Damm M, et al. Parosmia is Associated with Relevant Olfactory Recovery After Olfactory Training. The Laryngoscope. 2020;131:618–23. doi:10.1002/lary.29277

- 9Apollo Trial Could Vitamin-A bring back your sense of smell after Covid? University of East Anglia Rhinology and ENT Research Group. https://rhinology-group.uea.ac.uk/apollo-trial/ (accessed 29 Mar 2022).