In October 2020, the NHS became the first healthcare system in the world to commit to a net-zero target1. The Health and Care Act 2022 strengthened this commitment, placing new duties on integrated care boards (ICBs) and NHS trusts to consider sustainability in their decision making2. In 2022, each trust and ICB was asked to produce a ‘green plan’, allowing them to set out aims, objectives and delivery plans for carbon reduction, and these are scheduled to be refreshed by July 20251.

Medicines, which account for one quarter of NHS carbon emissions, are a crucial component of achieving the net-zero target1. Anaesthetic gases and inhalers make up 5% of NHS carbon emissions between them, with the rest mainly in manufacturing and the medicines supply chain.

However, since the initial net-zero fanfare in 2020, the NHS has grappled with a global pandemic, funding struggles, growing demand for services, and a change of government. Additionally, in March 2025, it was announced that NHS England is to be scrapped, with heavy cuts to ICB staff3. All of these factors have the potential to derail sustainability goals.

Progress so far

There has been some progress. Among the big wins already cited by NHS England are the NHS-wide decommissioning of desflurane — a particularly environmentally damaging anaesthetic gas — an ongoing programme to cut waste of anaesthetic gas nitrous oxide, and switching respiratory patients to higher quality, lower carbon care4.

NHS suppliers have also been tasked with publishing a carbon reduction plan and, from April 2027, will be required to publicly report targets and emissions.

NHS England data obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal under the Freedom of Information Act have revealed a 13% reduction in total emissions of mixed nitrous oxide (more commonly known as ‘gas and air’) between 2020 and 2024, from 183,757 to 159,314 tCO2e. For pure nitrous oxide, the drop in emissions was 31% over the same period, down from 81,563 to 56,609 tCO2e (see Figure 1).

There has also been a decline of 33% in the average emissions for short-acting beta-2 agonist (SABA) inhalers prescribed in primary care, from 24.2kgCO2e in 2020 to 16.1kgCO2e during the first 11 months of 2024.

This follows national incentives for primary care to switch people from the Ventolin Evohaler (salbutamol sulfate; GSK) to the Salamol inhaler (salbutamol sulfate; Teva UK), which is associated with less than half of the carbon emissions.

However, the percentage of non-SABA inhalers that are metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) has barely shifted from 56.2% in 2020 to 56.3% in 2023 and 55.7% for the first 11 months of 2024 (see Figure 2).

Nuala Hampson, pharmacy lead at the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, explains that changing from Ventolin to Salamol was a simple switch that many areas will have done by bulk. However, moving people on non-SABA medicines from MDIs to dry-powder inhalers (DPIs) is more complex.

“The next step — switching people over from MDIs to DPIs — is much harder [and] requires some clinical decision making, person-centred discussions and a face-to-face appointment to ensure good inhaler technique. So this change is likely to happen much more slowly.”

Hampson strongly believes there is a much broader context to sustainable healthcare that needs to be considered beyond the focus on inhalers.

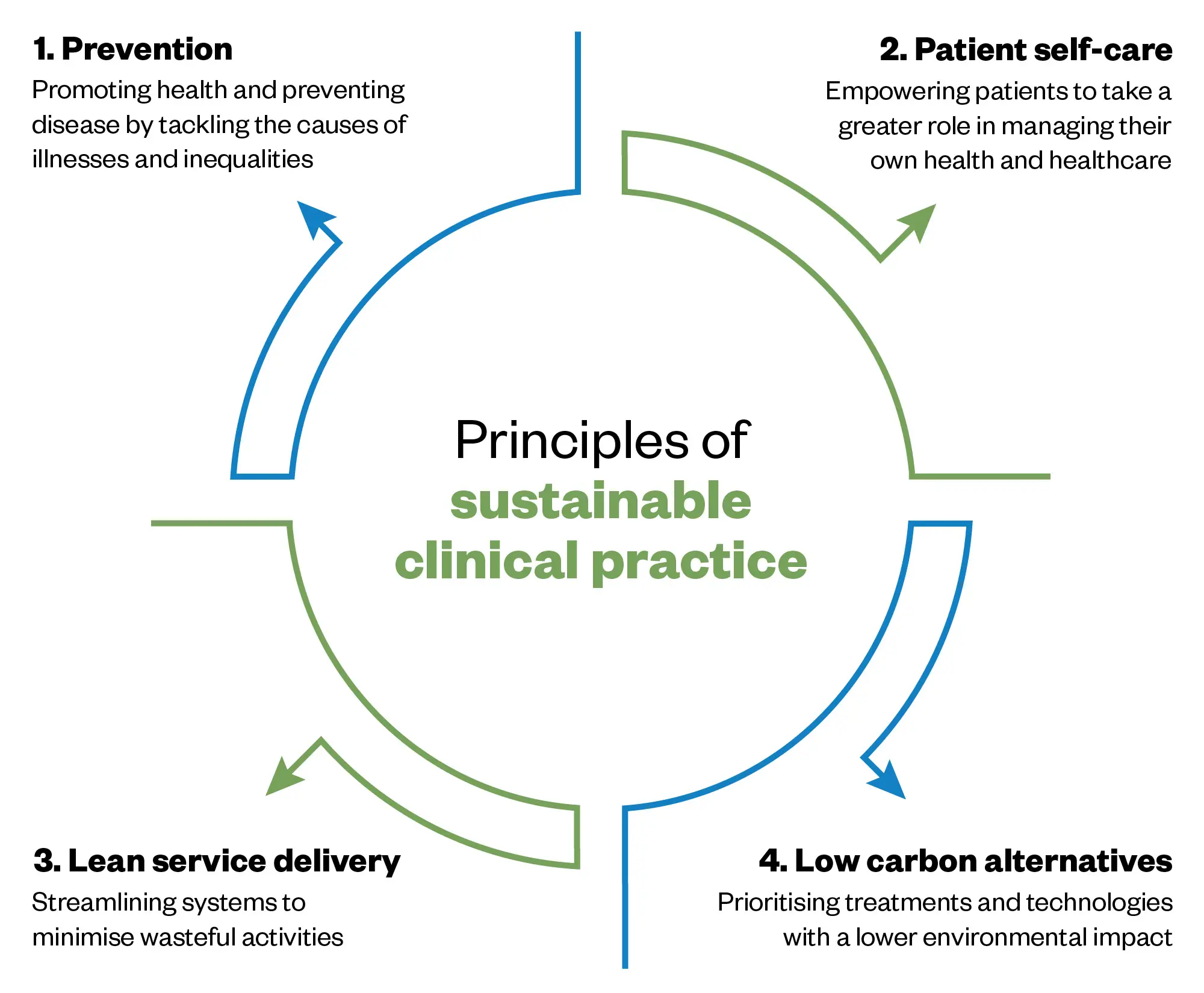

The principles of sustainable healthcare look at whether you can prevent someone needing a medicine in the first place by tackling the causes of disease and health inequalities, and empowering patients to take a greater role in managing their own health (see Figure 3).

Adapted from Centre For Sustainable Healthcare

Cutting waste

In general, people being prescribed medicines they never take or do not need is a huge problem, Hampson explains.

10% of medicines don’t need to be prescribed in the first place, and 30–40% of patients just don’t take the medicines as prescribed

Nuala Hampson, pharmacy lead at the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare

“If you look at the [‘National overprescribing [review] report’, [published in 2021], 10% of medicines don’t need to be prescribed in the first place, and 30–40% of patients just don’t take the medicines as prescribed. We need to address that by engaging with patients to make shared decisions around medicines,” she says5.

It has been estimated that every £1 spent on pharmaceuticals generates greenhouse gas emissions of 0.1558kg CO2e5. A report on medicines optimisation, published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in 2017, calculated that avoiding £150m of unused medicines equates to total avoidable emissions of 23,400 tCO2e from the manufacturing and supply of pharmaceuticals6.

Through its Pharmacy Sustainability Network, the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare showcases quality improvement projects, including reducing medicines waste in hospitals, encouraging patients to only order what they need in the community, using low-carbon alternatives, and supporting patients with non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as social prescribing.

Hampson points to work done by Deborah Gompertz, a complex care GP in Somerset, who began a project to reduce medicines waste in 2021 during home visits. A 12-week ‘Show me your medicines’ pilot of 40 patients found large amounts of waste. Replicating the scheme in a retirement village, community team members again found hundreds of boxes of unused medicines. The scheme has now been expanded to include patients admitted to the local hospital.

“If you did it across the whole of England, expanding to 1,250 primary care networks, that would be 1 million prescription items and £13m of waste in 12 weeks,” says Gompertz, who continues to conduct regular training and webinars to spread the word about medicines waste. In the 12-week project for complex patients in the community, Gompertz estimates a 1,693kg saving in avoidable carbon emissions.

In NHS England’s ‘Green plan guidance’ for ICBs, published in February 2025, there is reference to the principles of sustainable healthcare alongside a focus on five clinical areas that have high carbon volume, including mental health and long-term conditions, notes Hampson7. “It’s good to see these are gradually becoming part of the norm.”

The challenge is in scaling up at speed, she adds. “[The] ‘Greener NHS [programme’] has to prioritise the big wins, like the work they’ve done with the nitrous oxide toolkit” but relying on local champions is not enough, she argues. Progress on the principles of sustainable healthcare will need national incentives, as had happened with inhaler switches, she adds. “It does move things on faster.”

One change Hampson would like to see is prescribing formularies considering wider environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals. “It needs to be taken into account, as well as just the financial cost, because that changes the argument.” But that would need to be carefully implemented given some pharmaceutical companies have used carbon offsetting to label their products as carbon neutral, which she says does not go down well with sustainability experts. Some work on environmentally informed pharmaceutical prescribing has been done in Scotland but it has not yet been implemented.

I would personally love to see nationally co-ordinated, patient education campaigns regarding medication waste

Tracy Lyons, principal pharmacist for medicines optimisation and sustainability lead at NHS Dorset

Tracy Lyons, principal pharmacist for medicines optimisation and sustainability lead at NHS Dorset, says “there’s a huge amount of enthusiasm for making a difference” among ICBs as they update their green plans, particularly in light of updated joint NICE/BTS/SIGN guidelines in November 2024, which are central to sustainable medicines management for respiratory patients.

“However, it’s imperative this isn’t now lost as ICB teams transition to new activity and responsibilities,” she adds.

Enacting system change is always easier when there is a clear mandated or centrally coordinated expectation, as was seen with the decommissioning of desflurane, says Lyons.

“I would personally love to see nationally coordinated, patient education campaigns regarding medication waste.”

In Dorset, Lyons has spearheaded two projects that have shown both environmental impact and reduced spending. The ‘Only order what you need’ campaign, which empowered patients to decline unnecessary repeat prescriptions, led to 65,000 fewer prescriptions collected, saving £450,000 and preventing 300 tCO2e in just two months.

“Perhaps even more importantly, we estimate it liberated over 1,000 hours of healthcare professional time and was positively received by patients,” says Lyons.

A process of systematised structured medication reviews in thousands of high-risk patients also led to reduced medicines use and hospital admissions in that cohort over the past year, she adds.

What frustrates Lyons the most is the lack of vocal leadership within the senior echelons of the NHS. “I want a clear linkage between excellence in patient care, economic management and the principles of sustainable healthcare so that everyone understands that ‘green health’ isn’t a nice to do, it’s an essential for every part of the system,” she says.

Recycling

Another part of the net-zero story is recycling. This has proven difficult to get a handle on because it requires many parts of the system, including the NHS, different pharmaceutical companies, pharmacies and patients, to be on board. Various schemes are being trialled.

However, an inhaler recycling project that first showed its value in East Kent is being closely watched for its potential to become a permanent national scheme. ‘Re-Hale,’ a partnership initially between pharmaceutical company Chiesi and NHS Kent and Medway ICB, encourages patients to drop used or unwanted inhalers at the pharmacy to be picked up by Alliance Healthcare. The propellants are recycled by Grundon, a waste management company.

Between September 2023 and November 2024, more than 41,000 inhalers were recycled through the scheme, saving 176 tonnes of carbon. The return rate of 5.5% is more than any other UK inhaler recycling scheme has achieved so far. The team is now rolling out the programme to the whole of the Kent and Medway ICB region.

Sam Coombes, lead medicines information technician and sustainability lead at East Kent Hospitals University Foundation Trust, explains that while there was some initial resistance owing to time constraints in community pharmacy, with 55% signing up in East Kent, more and more are now coming on board, joining the dispensing GPs and hospital pharmacy teams also involved in the scheme.

“We didn’t want it to end at the pilot and just be another effort in recycling, so we looked at partners for expansion,” explains Coombes.

Along with Cath Cooksey, lead medicines optimisation pharmacist in Medway ICB, Coombes found a partner in CiPPPA (Circularity in Primary Pharmaceutical Packaging Accelerator), a not-for-profit collaboration between pharmaceutical companies, including Chiesi, manufacturers and other stakeholders, to improve sustainability in packaging.

We’re looking at how do we take this [inhaler recycling scheme] to the whole of the UK

Sam Coombes, lead medicines information technician and sustainability lead at East Kent Hospitals University Foundation Trust

“We’ve got the next 12 months to prove the scalability,” explains Coombes. “We’re looking at how do we take this to the whole of the UK.”

CiPPPA, which officially launched in 2024, has three workstreams — inhalers, blister packs and injectables. Its figures show that around 70 million MDIs are used annually in the UK, and while the UK produces 2 to 2.5 billion blister packs annually, only 5% are recovered.

CiPPPA’s long-term aim is more sustainable packaging, but the initial focus is on scalable recycling programmes that can be used nationwide. Competing firms are attempting to overcome some of the siloed working on recycling schemes that has happened in the past by sharing resources, solving logistical issues and pushing for regulatory change, CiPPPA says.

Other successful recycling schemes include Novo Nordisk’s PenCycle scheme and Boots’ blister pack recycling scheme, which recently expanded from a pilot in 100 stores to branches nationwide after 170,000 customers signed up.

Measuring impact

One of the difficulties of tracking progress on reducing the carbon footprint of medicines is how to measure it accurately. Inhalers and anaesthetic gases are one thing, but assessing the carbon footprint of medicines is not just about how and where they are made — it is about their use in patients and how they move around the system.

In an interview published in February 2025, John Warburton, chair of the UK Clinical Pharmacy Association, noted that procurement decisions on sustainability are hindered by a lack of reliable data around the medicines life cycle8.

The British Standards Institute is currently working on a process to develop environmental impact standards for pharmaceuticals, but this is incredibly complex and likely to take some time.

You get a lot of rebranding of services as being sustainable, but they’re not actually sustainable

Alifia Chakera, head of pharmaceutical sustainability for the Scottish government

Alifia Chakera, head of pharmaceutical sustainability for the Scottish government, says the NHS needs to do more of these careful calculations.

Chakera, a clinical pharmacist, led on the ‘Nitrous oxide project’ at NHS Lothian, which has informed work across the UK after showing that a significant portion of nitrous oxide emissions was waste from the piped system9.

“My observation is that you get a lot of rebranding of services as being sustainable, but they’re not actually sustainable. I’m really excited by the enthusiasm, but I still think we need to follow the scientific method because this is about managing scarcity of resources.”

She still sees far too much greenwashing and misdirected effort. “We do need greater emphasis on where we have strong evidence, we need more rapid implementation of quality measures.”

Chakera is currently working on a green paper for the Scottish government to better understand medicines waste and harms, taking a systems approach to track how medicines move around the supply chain and then to patients, and identify areas for improvement.

Alongside this, NHS Scotland and the Scottish government have launched a challenge to come up with technological solutions to enable unused medicines to be safely reabsorbed into the supply chain for redistribution10.

Wales has set its own targets for cutting medicines waste as part of a five-year plan published by the All-Wales Medicines Strategy Group in April 202411. A raft of initiatives includes national prescribing targets for inhalers, the carbon footprint of which is being tracked carefully on a three-monthly basis12. Wales has also moved away from 28-day prescribing intervals where appropriate to reduce the carbon impact of monthly visits to the GP practice and community pharmacy to order and collect prescriptions. Interactive dashboards run by the All-Wales Therapeutics and Toxicology Centre allow NHS staff to drill down to GP level to see how they are progressing on various indicators.

‘Greener pharmacy toolkit’

For pharmacy specifically, the long-awaited Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) ‘Greener pharmacy toolkit‘ launched on 8 April 202513. Developed in collaboration with the NHS, the toolkit has been developed to guide pharmacies — with separate versions for hospital and community pharmacies — through steps they can take to achieve bronze, silver and gold status in reducing their carbon footprint across six domains, including clinical practice. The RPS says the toolkit will continue to adapt and in future phases could be used for regional oversight.

This is about how to make pharmacy sustainable for the future

Minna Eii, advanced pharmacist practitioner at South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust and a co-founder of Pharmacy Declares

Minna Eii, advanced pharmacist practitioner at South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust and a co-founder of Pharmacy Declares, a group of environmentally conscious pharmacy professionals, helped to develop the toolkit, which she believes will make it easier for pharmacies to adopt sustainable practices.

Eii says she sees little pockets of sustainability activity in specialist areas that cannot be easily disseminated or implemented by others because the infrastructure to do that does not exist. Or because people are reluctant to change because they have always done something a certain way. Initiatives like the RPS toolkit should help, she adds.

“This is about how to make pharmacy sustainable for the future. It’s not just saving your carbon footprint, not just about emissions, it is about making your life easier, being more efficient and improving patient care.”

- This article was amended on 19 May 2025 to reflect that Wales has moved away from, rather than towards, 28-day prescribing intervals. In addition, a sentence about the number of injectables manufactured by CiPPPA members was removed and it was made clear that CiPPPA is not connected to Novo Nordisk’s PenCycle scheme or Boots’ blister pack recycling scheme.

- 1.Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service. NHS England. October 1, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2022/07/B1728-delivering-a-net-zero-nhs-july-2022.pdf

- 2.Health and Care Act 2022. Legislation.gov.uk. April 28, 2022. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/31/contents

- 3.PM remarks on the fundamental reform of the British state: 13 March 2025. Gov.uk. March 13, 2025. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-remarks-on-the-fundamental-reform-of-the-british-state-13-march-2025

- 4.System progress. NHS England. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/whats-already-happening/

- 5.Good for you, good for us, good for everybody:A plan to reduce overprescribing to make patient care better and safer, support the NHS, and reduce carbon emissions. Department of Health and Social Care. September 22, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/614a10fed3bf7f05ab786551/good-for-you-good-for-us-good-for-everybody.pdf

- 6.Environmental impact report: Medicines optimisation Implementing the NICE guideline on medicines optimisation (NG5). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. September 1, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/Into-practice/resource-impact-assessment/Medicines-optimisation-sustainability-report.pdf

- 7.Green plan guidance. NHS England. February 4, 2025. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/green-plan-guidance/

- 8.Janković S. John Warburton on positioning pharmacists at the heart of clinical teams. Hospital Pharmacy Europe. February 26, 2025. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://hospitalpharmacyeurope.com/pharmacy-practice/john-warburton-on-positioning-pharmacists-at-the-heart-of-clinical-teams/

- 9.East Lancashire Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trus. Case study – Nitrous Oxide: The Great Escape. NHS England. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/north-west/greener-nhs/case-studies-greener-nhs/case-study-nitrous-oxide-the-great-escape-at-east-lancashire-hospitals-trust/#:~:text=What%20action%20was%20taken%3F,and%20its%20significant%20environmental%20impact

- 10.Challenge 10.8 How can technology reduce pharmaceutical waste? CivTech. July 30, 2024. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.civtech.scot/civtech-10-challenge-8-reducing-pharmaceutical-waste

- 11.All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. AWMSG Strategy for Wales: 2024-2029. NHS Wales. April 2024. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://awttc.nhs.wales/about-us1/our-reports-and-strategies/medicines-strategy-for-wales/awmsg-strategy-for-wales-2024-2029/

- 12.NHS Wales inhaler carbon footprint reports. NHS Wales . Accessed May 12, 2025. https://awttc.nhs.wales/medicines-optimisation-and-safety/medicines-optimisation-guidance-resources-and-data/prescribing-analysis/publications/nhs-wales-inhaler-carbon-footprint-reports/

- 13.RPS Greener Pharmacy Guides and Toolkit. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. April 8, 2025. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.rpharms.com/greenerpharmacy

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

We need to look at the wastage incurred with original pack dispensing for hospital inpatients. What do we do with part used packs that are returned to pharmacy when prescriptions are changed? - recycle them or dispose of them - both of which are costly.

Unit dose dispensing eliminates wastage , reduces nursing and pharmacy time and eliminates drug administration errors.