Mclean/Shutterstock.com

While many industries suffered financial blows during the COVID-19 pandemic, the online shopping market was not one of them.

According to the Office for National Statistics, online sales rose to a record high of 33.9% as a proportion of all retail spending in 2020. A report by delivery management company Metapack, published in March 2022, suggested this trend could be here to stay, with more than a quarter of surveyed consumers expecting to stick with online shopping preferences after the pandemic ends.

The increasing preference for online purchases has not been limited to clothing and groceries.

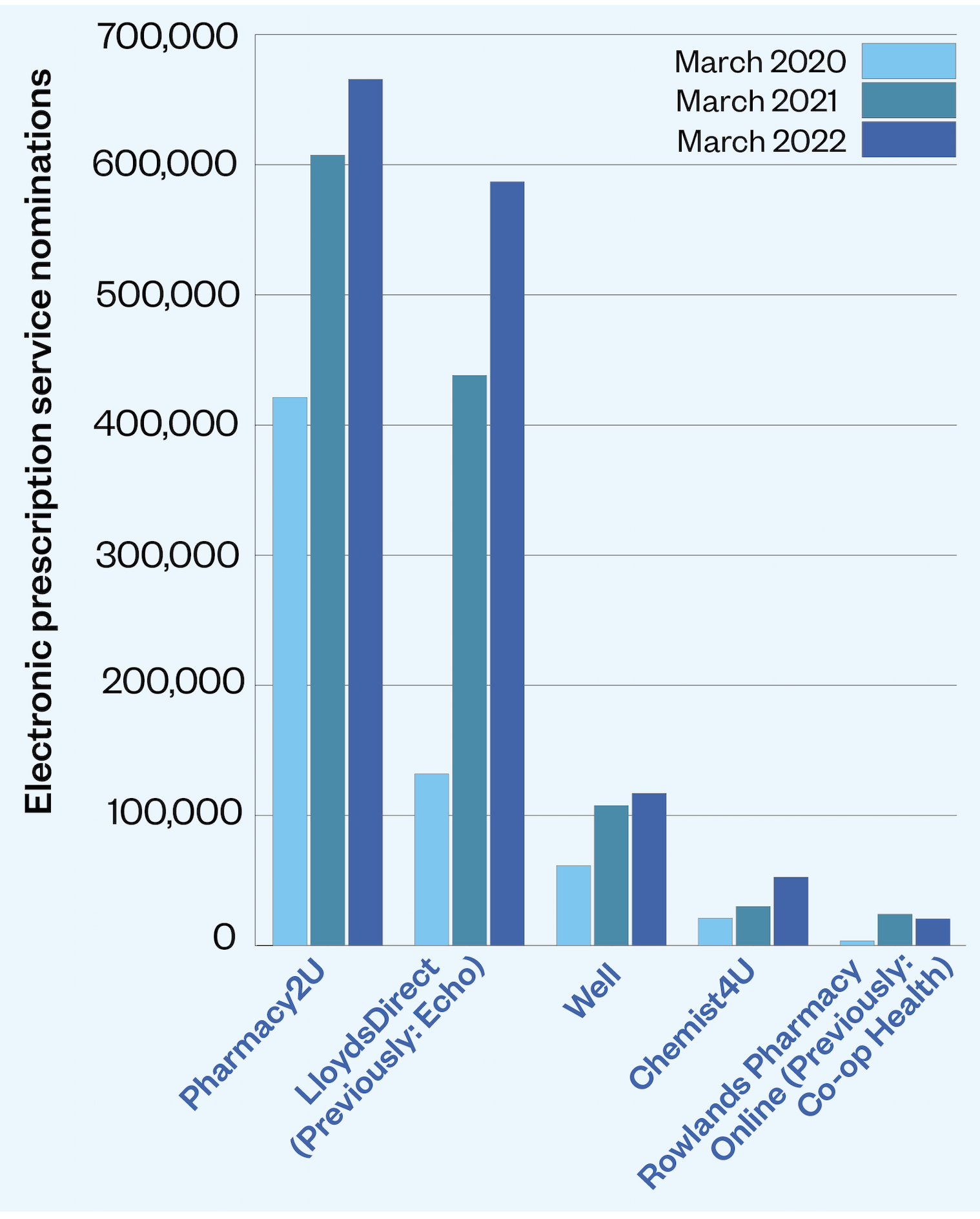

Distance-selling pharmacies — more commonly known as ‘online pharmacies’ — have also grown in popularity over the course of the pandemic. Figures from NHS Digital show that the number of patients nominating online pharmacies as their preferred option for receiving medicines through the electronic prescription service (EPS) nearly doubled from 999,498 to 1,950,497 between March 2020 and March 2022 (see Figure).

The market for these pharmacies has also grown in recent years, with dispensing through online pharmacies increasing fourfold in five years, from 13.2 million items in 2016 to 52.9 million items in 2021. Meanwhile, over the same time frame, the number of items dispensed by all community pharmacy contractors in England increased by just 2.3%, from 1.104 billion items in 2016 to 1.129 billion items in 2021.

But as the popularity of using online pharmacies skyrockets, their safety has been called into question.

An analysis by The Pharmaceutical Journal of inspection reports published by the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) — which regulates all pharmacies, including those dispensing at a distance — reveals that online pharmacies are more likely than ‘bricks-and-mortar’ pharmacies to fail at meeting all five regulatory standards.

The reports analysed covert inspections carried out since April 2019, when the regulator began publishing reports on its website.

Of the 129 online pharmacies that had been inspected by the GPhC as of 30 March 2022, 28 (21.7%) were found to have failed to meet at least one standard following their most recent inspection and nearly a third (40 online pharmacies) have received a failed inspection report at some point since April 2019.

For comparison, of the 2,808 ‘bricks-and-mortar’ pharmacies that had been inspected as of 30 March 2022, just 2.6% (75 pharmacies) were found to have failed to meet at least one standard following their most recent inspection and just 15% (430) have received a failing inspection at some point since April 2019.

Our inspectors are continuing to identify serious patient safety concerns in some pharmacies providing online prescribing services

Duncan Rudkin, chief executive of the General Pharmaceutical Council

Duncan Rudkin, chief executive of the GPhC, says the regulator conducted a programme of online pharmacy inspections “directed at those where concerns had been raised as well as those that were selling/prescribing higher risk medicines or working with overseas prescribers”.

“Our inspectors are continuing to identify serious patient safety concerns in some pharmacies providing online prescribing services,” he says, adding that between April 2019 and December 2021, “we have taken enforcement action against 48 online pharmacies to protect patient safety”.

“By carrying out targeted inspections in higher risk areas, we have naturally found more pharmacies that are not meeting our standards — which is exactly why we are focusing our efforts in this way, in order to prioritise patient safety.”

Following this targeted inspection programme, Claire Bryce-Smith, director of insight, intelligence and inspection at the GPhC, wrote to pharmacy trade bodies in August 2021 warning of “patient safety concerns relating to pharmacies dispensing medicines prescribed by EEA prescribers working alone or for online prescribing services”.

“Our inspections found that our standards were not being met and our guidance on providing pharmacy services at a distance was not being followed,” the letter says.

According to the guidance for online pharmacies, published in April 2019 and updated in March 2022, online pharmacies are allowed to work with prescribers based overseas, but must ensure that these prescribers are not “trying to circumvent the regulatory oversight put in place within the UK”.

Where pharmacy services involve working with prescribers or prescribing services based outside of the UK, contractors are required to ensure that “the prescriber is registered in their home country where the prescription is issued and can lawfully issue prescriptions online to people in the UK”, the guidance states.

It adds that the contractor should also ensure the overseas prescriber “is working within national prescribing guidelines for the UK”.

The Pharmaceutical Journal’s analysis reveals that a third of the inspection reports for failing online pharmacies highlight that the pharmacy in question has links to prescribing services based outside of the UK — most commonly in Romania, as well as the Czech Republic and Germany — that enable them to avoid regulation by the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

The inspection reports of these failing online pharmacies make for alarming reading.

At one such pharmacy, FCL Chemist in Derbyshire, which uses an online prescribing service based in Romania, “95% of prescriptions dispensed were for opioids and z-drugs”. However, the pharmacy could not provide evidence that it “reviews prescribing to prevent misuse or abuse”.

The inspector reported one incident where the pharmacy had supplied a patient with 100 codeine phosphate 30mg tablets “on six separate occasions within a five-month period”. The patient had refused to give consent to contact his GP but was required to provide a GP report before a seventh supply could be made.

“This showed that codeine (co-codamol 30/500) had only been prescribed by the GP on one occasion, which was after the person had received six supplies from the pharmacy, and it was listed as an acute medicine,” the inspection report says.

Elsewhere, at Pharmacy First in Manchester, which uses prescribing services based in the Czech Republic, an inspector reported a case “which would indicate that a person might be overusing codeine-containing medicines”, having obtained Solpadeine or Nurofen Plus from the pharmacy for four years and receiving “8 orders over the past 12 months”.

“This was not in line with the current guidance which specifies that medication containing codeine is for short-term use only and for a maximum of three days,” the report says.

Homecare Pharmacy in the West Midlands, where “nearly all of the prescriptions dispensed were for opioids and z-drugs”, was also found to be using a Romanian-based online prescribing service, as well as “an accountant with no pharmacy training” to perform the secondary approval of some medicine orders.

“This was a check for clinical appropriateness, and he was not adequately qualified to do this,” the report says.

The inspectors found evidence that repeated supplies to patients “were made without any pharmacy intervention”, with examples including 13 supplies of 100 dihydrocodeine 30mg tablets made to one patient within a ten-month period and 7 supplies of 14 zopiclone 7.5mg tablets in an eight-month period.

As the inspection report notes: “Repeat prescribing of z-drugs does not comply with current clinical guidance for short term insomnia, which recommends referral for cognitive behavioural therapy if z-drugs are required for more than two weeks.”

During the inspection, the pharmacy was unable to confirm “whether the prescriber was registered or authorised to prescribe for UK patients”, having received a registration certificate written in Romanian “via WhatsApp”.

Despite these reports, the GPhC is restricted in its response by its regulatory remit. While the regulator is able to monitor the standards of registered online pharmacies and the pharmacy staff that work there, the CQC inspects the online primary care providers that write the prescriptions.

But neither regulator has a remit that extends to monitoring the services provided to UK patients by prescribers based overseas.

The CQC has long been on a mission for this to change.

Our view is that as digital services grow in popularity, and breadth, over the coming decade there is a gap in government’s power to intervene where harm is being caused

Care Quality Commission

In August 2017, the CQC, along with seven other regulators, including the GPhC, agreed to share intelligence about online providers to improve regulatory coverage.

This was followed by the submission of legislative proposals to the DHSC, in part to address “safety gaps” in the CQC’s “limited jurisdictional ability for UK regulators to take action in response to harmful prescribing by providers or registered persons based outside the UK”.

In evidence submitted to the Health and Social Care Select Committee in April 2021, the CQC noted that it had “current examples of death and severe harm caused by digital services delivered from outside England”.

“Our view is that as digital services grow in popularity, and breadth, over the coming decade there is a gap in government’s power to intervene where harm is being caused,” the evidence document continues.

In a statement to The Pharmaceutical Journal on 4 April 2022, the CQC said that it has “taken action where the law allows us through our enforcement action and prosecuting unregistered providers, including an example recently where the company was based in England but using General Medical Council doctors outside of the country”.

In February 2022, [the online branch of] Pharmacorp Ltd (also known as Medicine Direct) was ordered to pay £13,670 by Tameside Magistrates’ Court after the CQC found high strength co-codamol, pregabalin and gabapentin was prescribed to patients by UK-registered doctors who were based in Romania.

Pharmacorp Ltd is also a registered pharmacy but has not yet been inspected by the GPhC.

“For services that we regulate, we are able to challenge poor care and drive improvement, but we share concerns about the ability for some providers to work with little or no regulatory oversight because of the way in which they have established their business model,” says Mani Hussain, deputy chief inspector of primary medical services and integrated care at the CQC.

“If people are being exposed to risk because services are set up in a way that avoids or minimises the scrutiny designed to protect them, something needs to change.

“This is why we have been working with our regulatory partners and the DHSC to address the current regulatory gaps and the risks that they present to people.”

When asked about progress on the legislative proposals put forward by the CQC, the DHSC said it would consider them “in due course”, adding that it was currently undertaking a review of CQC regulations, which it said was a statutory requirement.

“Patient safety is our top priority, and we expect doctors and pharmacists to apply the same high standards for remote prescriptions and advice as they do for face-to-face appointments,” the spokesperson said.

Despite the DHSC’s expectations, patients’ lives still hang in the balance and it is now in the government’s power to close a loophole in regulation that has plagued the online pharmacy sector for years — one that will only grow as demand continues to surge.

FCL Chemist, Pharmacy First, Homecare Pharmacy and Pharmacorp Ltd were all approached for comment.