Alfred Pasieka / Science Photo Library

In 2003, French researchers identified high levels of a protein in a family with familial hypercholesterolaemia, an inherited disease that leads to dangerously high blood cholesterol and, consequently, increased risk of cardiovascular disease[1]

. The protein, called proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), had been discovered earlier that year by Canadian researchers[2]

.

A series of experiments from different laboratories subsequently showed that high levels of PCSK9 stopped the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors from functioning.

Three years later, the results of a large community study mapping LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and the incidence of coronary heart disease against mutations in the PCSK9 gene were released[3]

. Those with genetic variations linked to reduced PCSK9 function were found to have significantly lower LDL-C levels and lower risk of coronary heart disease. The hypothesis that inhibiting PCSK9 activity could reduce cholesterol became an important research topic.

“This led to experimental studies in animal models showing that inhibition of PCSK9 was a potent way to reduce cholesterol levels in blood,” explains Prediman Krishan Shah, director of the Oppenheimer Atherosclerosis Research Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Cardiovascular diseases are the number one killer across the globe, with an estimated 17.5 million people dying from one of these disorders in 2012 — 31% of all deaths. One of the risk factors is atherosclerosis: caused when high levels of LDL-C in the blood build up in the inner walls of arteries, thickening them and provoking an inflammatory response, it can lead to heart attack or stroke. Levels of LDL-C are therefore often used as a surrogate marker for the risk of having a cardiovascular event.

Statins, which have been on the market for almost 30 years, are the primary therapy used to prevent cardiovascular events. They lower LDL-C levels by inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which has a vital role in the production of cholesterol in the liver. Statins typically reduce LDL-C levels by 30–40% (depending on the dose and statin) and are directly associated with reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke.

However, although hugely successful in terms of sales — Pfizer’s atorvastatin (Lipitor) is the bestselling drug of all time — for many, statins are ineffective or the side effects are intolerable. “We cannot achieve very low levels of LDL-C in the majority of patients,” says John Kastelein, professor of medicine at the Department of Vascular Medicine at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

We cannot achieve very low levels of LDL-C in the majority of patients

Hoping to address this unmet need, the drug development pipelines of some biopharmaceutical companies feature novel candidates to lower LDL-C. Perhaps the most eagerly anticipated are the PCSK9 inhibitors, several of which have been shown to reduce LDL-C levels in clinical trials. However, whether they will ever be prescribed as widely as statins will depend on whether they can be shown to have a positive effect on clinical outcomes, as well; a number of major studies looking at their impact on cardiovascular events are ongoing.

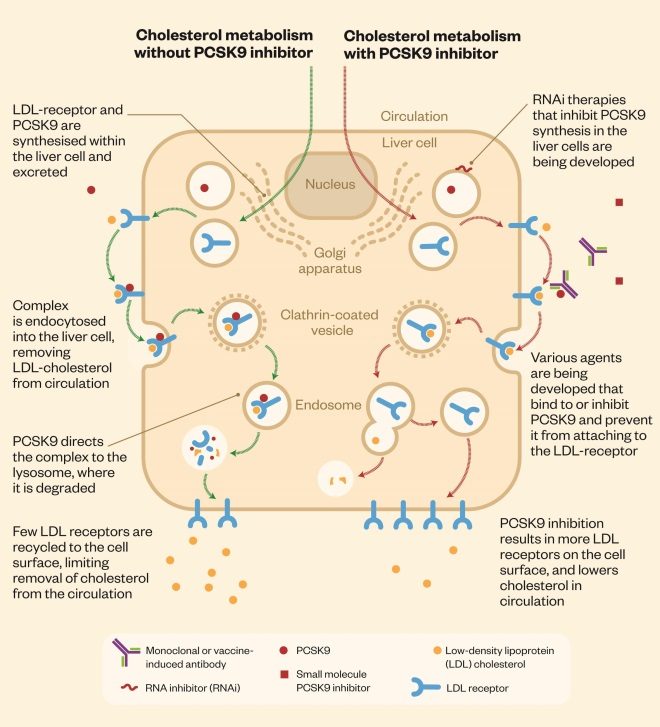

The PCSK9 protein interferes with the clearance of LDL-C from the blood. LDL receptors on liver cells remove LDL-C from the blood by binding it and then moving it into the cell for elimination. The lipid-free receptors then return to the surface of the cell. When PCSK9 binds to the LDL receptor, however, the receptor is unable to re-emerge on to the cell surface to remove more LDL-C, which then remains in the blood. By inhibiting the PCSK9 protein, PCSK9 inhibitors essentially improve the liver’s ability to recycle LDL receptors, resulting in a greater number of receptors on the cell surface and enabling more LDL-C to be removed from circulation (see ‘Cholesterol metabolism and PCSK9 inhibitors’).

Cholesterol metabolism and PCSK9 inhibitors

The PCSK9 protein interferes with clearance of cholesterol from the blood. Several PCSK9 inhibitors are being developed, which improve the liver’s ability to recycle low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors, enabling more cholesterol to be removed from the circulation.

Drugs race

There are thought to be around 20 PCSK9 inhibitors in development (see ‘Selected PCSK9 inhibitors in developmen

t’), but the two frontrunners are Amgen’s evolocumab (Repatha) and Regeneron/Sanofi’s alirocumab (Praluent). Both drugs are injectable monoclonal antibodies that appear to be highly effective at reducing LDL-C levels, achieving an additional 60–75% reduction in patients taking statins.

So far, no serious adverse events have been reported in phase III clinical trials. Common side effects include injection site reactions, and cold and flu-like symptoms. However, Amgen and Regeneron/Sanofi are assessing potential neurocognitive side effects, such as memory loss and confusion. And Kastelein says it is possible that the body’s own antibodies to the monoclonal antibody treatments could cause rare problems over the long term — something that will emerge through continued surveillance once the treatments reach market.

PCSK9 inhibitors are expected to work synergistically with statins. Most of the benefit of statin treatment comes from a low dose; doubling the dose increases LDL-C reduction by only another 6%, according to Sotiris Antoniou, consultant pharmacist in cardiovascular medicine at Barts Health NHS Trust. “Part of the reason is that the body compensates by increasing levels of PCSK9,” he explains. Adding PCSK9 inhibitors to statins, therefore, should result in a much greater reduction in LDL-C.

The race to be first to market is on. Amgen was the first to seek regulatory approval for a PCSK9 inhibitor with its application to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for evolocumab in August and September 2014, respectively. But Regeneron/Sanofi could yet beat Amgen to it. The marketing authorisation application for alirocumab was accepted by the EMA and FDA in January 2015, but the FDA has agreed to speed up the process by selecting it for priority review, aiming for a six-month turnaround. Hot on their heels is Pfizer, whose PCSK9 inhibitor bococizumab (RN316) is currently in phase III trials.

Initial regulatory submissions for evolocumab and alirocumab are based on results from phase III studies of their safety and efficacy in lowering LDL-C. These studies have shown that evolocumab can lower LDL-C up to 75% further in patients already treated with statins[4]

, up to 56% more in those unable to tolerate statins[5]

, and can maintain reductions in LDL-C over 52 weeks[6]

with low incidence of adverse effects. Treatment with evolocumab can also lower LDL-C by an additional 61% in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia who are already being treated with another therapy[7]

.

Similarly, phase III trials have shown that alirocumab can reduce LDL-C by an additional 62% in patients already receiving statins[8]

. Data from three trials presented at the European Society of Cardiology meeting in Barcelona in September 2014 suggest that alirocumab is better than either a non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug (ezetimibe) or placebo at reducing LDL-C levels in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia, a history of intolerance to statins, or both.

Despite their safety and efficacy in reducing LDL-C levels, the general consensus is that the phase III data for both evolocumab and alirocumab will result in their approval for use only in restricted indications — patients who have familial hypercholesterolaemia or who are intolerant to statin therapy.

“The profile of the anti-PCSK9s looks extraordinarily good in terms of safety and efficacy,” says Eric Schmidt, research analyst at Cowen and Company in New York. Although he acknowledges that the convenience of the drugs “could be improved upon” (they require an injection once or twice a month), he points out that this downside will be outweighed by the potential benefits for patients who are hard to treat. Schmidt concludes: “We believe the profile of the anti-PCSK9s will be difficult to match, and that they will gain broad use over time in these severe patients.”

The profile of the anti-PCSK9s looks extraordinarily good in terms of safety and efficacy

Outcomes versus biomarkers

The clinical community, however, will be inclined to wait for the culmination of major outcome studies before prescribing PCSK9 inhibitors for many patients, according to an analyst on the cardiovascular and metabolic disorders team at GlobalData, London[9]

.

It is generally accepted that decreasing LDL-C levels by 1 mmol/l results in a 10% reduction in the risk of having a cardiovascular event, according to Antoniou. “Whilst the evidence for reducing LDL is well accepted, we are fortunate in cardiovascular disease that prescribing is almost completely based on outcomes,” he says. “As such, until outcomes have been associated with PCSK9 inhibitors, they are likely to be reserved for patients with somewhat greatly elevated risk of cardiovascular disease.”

There is often much focus on lowering levels of LDL-C as a way to reduce cardiovascular risk, but there has been some controversy as to whether this biomarker really does translate into a reduction in cardiovascular events.

For a long time, ezetimibe (trade name Zetia, Merck; marketed in Europe as Ezetrol, MSD) was a case in point. Way back in 2002, the FDA approved ezetimibe, a cholesterol-lowering agent that inhibits absorption of cholesterol by the small intestine, for use singly or in conjunction with statins. Daily ezetimibe tablets alone can reduce LDL-C levels by around 17% and by more when combined with a statin[10]

, although the treatment is associated with muscle weakness and pain, and other rarer side effects, such as jaundice, chest pain and pancreatitis.

Despite the fact that ezetimibe can lower LDL-C levels significantly, many clinicians were unconvinced that it was effective at preventing cardiovascular diseases — a concern compounded by a 2008 study showing that adding ezetimibe to a statin (simvastatin, trade name Zocor; Merck) had no effect on athersclerosis progression, as judged by changes in the thickness of the innermost layers of the artery wall[11]

. Antoniou says the lack of outcome-based data meant that ezetimibe was not routinely used.

However, more than ten years after it was approved, the results from a seven-year outcomes study (IMPROVE-IT) comparing simvastatin and a combination pill containing simvastatin and ezetimibe (Vytorin, Merck; marketed in Europe as Inegy, MSD) demonstrated that ezetimibe is able to prevent heart attacks and stroke, albeit modestly, in high-risk patients with established heart disease — findings that may have little consequence for ezetimibe, but huge implications for PCSK9 inhibitors.

The data show for the first time that a non-statin can prevent heart attacks and stroke, presumably through an incremental reduction in LDL-C when added to statin treatment.

Although the reduction in the cardiovascular event rate was only 2%, the study is, arguably, among the most influential in the history of LDL-C drug research, says the GlobalData analyst. This is because it validates the theory that LDL-C is a causative agent of cardiovascular disease and that its reduction with aggressive drug therapy can prevent cardiovascular events — a property that can no longer be considered unique to statins. As a result, the study is likely to affect the sales and regulatory status of all future LDL-C-lowering therapies, he says. This includes PCSK9 inhibitors, which already markedly outperform ezetimibe in terms of safety and efficacy in lowering LDL-C levels.

Both Amgen and Regeneron/Sanofi are undertaking expensive ongoing studies of cardiovascular outcomes to see whether further reductions in LDL-C by the addition of PCSK9 inhibitors in patients on statins will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes. Results for alirocumab’s ODYSSEY Outcomes trial are expected in January 2018 and for evolocumab’s FOURIER in December 2017.

Stumbling block

Inevitably, for PCSK9 inhibitors to be used broadly, one of the considerations will be price. Whereas the use of Vytorin could achieve low levels of LDL-C at an annual treatment cost of approximately US$2,350, PCSK9 inhibitors are likely to command the hefty pricing associated with monoclonal antibody therapies — or ‘biologics’ — which is in the range of US$10,000 to US$20,000 per year, says the GlobalData analyst[9]

. This stark price difference would be exacerbated by the arrival on the market of generic versions of Vytorin and ezetimibe, which are expected less than a year after the first PCSK9 inhibitors are likely to launch (late 2015). “As a cardiologist, do you prescribe the time-tested, scientifically established, low-cost treatment for your hard-to-treat patients, or do you go with the new, high-priced biologic? The answer will be the latter only in cases in which there are no other options — that is, in statin-intolerant, high-cardiovascular-risk patients,” he says[9]

.

At high prices, however, even a niche product could result in blockbuster sales. Evolocumab and alirocumab are drugs that will be taken by each patient for decades; furthermore, they are unlikely to suffer much generic competition because of the tight regulation surrounding biologic agents. News agency Reuters has reported that some analysts have forecast that certain PCSK9 inhibitors currently in development, including evolocumab and alirocumab, could reach US$2bn in peak annual sales[12]

.

And evidence for beneficial clinical outcomes is not far off. Sanofi and Regeneron released preliminary data from ODYSSEY LONG TERM at the European Society of Cardiology meeting in September 2014. A post-hoc safety analysis using a pre-specified endpoint that included coronary heart disease death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or unstable angina requiring hospitalisation, suggests that alirocumab roughly halves the number of heart attacks and strokes in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease. And analysis of ongoing studies suggests evolocumab can reduce cardiovascular events by 53%[13]

.

Shah concludes: “If outcomes based studies confirm preliminary data suggesting a reduced rate of cardiovascular events, and no additional new toxicity emerges, then PCSK9 inhibitors will clearly be a major advance in the lipid lowering space.”

Selected PCSK9 inhibitors in development

Vaccines

Relatively short half-lives mean monoclonal antibodies require regular injections. Vaccines that stimulate the immune system to generate high-affinity, long-lasting PCSK9-specific antibodies should overcome this limitation. Pfizer is among those developing a PCSK9 vaccine, which is expected to start clinical trials in 2016. Another is AFFiRiS, whose preclinical trials with three vaccine candidates (ATH04, ATH05, ATH06) have demonstrated a reduction of LDL-C levels in experimental animals after three to four vaccinations, lasting for up to ten months. Clinical studies are anticipated to begin in mid-2015.

Small molecules

For those who do not like injections, Pfizer is developing an oral PCSK9 inhibitor, currently in phase I trials. Additionally, Serometrix has an oral PCSK9 inhibitor in preclinical development, and Bristol-Myers Squibb is working on a PCSK9-binding drug, Adnectin (BMS-962476), also in preclinical studies. Kowa is developing a novel and potent cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor (K-312) that inhibits PCSK9 expression; K-312 is in phase I trials.

Gene therapy

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and The Medicines Company are developing RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutics that inhibit PCSK9 synthesis (the ALN-PCS programme). According to Alnylam, RNAi therapeutics can block PCSK9 synthesis across a wide range of plasma PCSK9 levels, which is useful because they are known to vary widely among individuals and to be elevated in association with statin therapy. ALN-PCS is currently in phase I trials.

References

[1] Abifadel M, Varret M & Rabès JP. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nature Genetics 2003;34:154–156.

[2] Seidah NG, Benjannet S & Wickham L. The secretory proprotein converstase nueral apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2003;100:928–933.

[3] Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr et al. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006:354(12): 1264–1272.

[4] Robinson JG, Nedergaard BS, Rogers WJ et al. Effect of evolocumab or ezetimibe added to moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy on LDL-C lowering in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the LAPLACE-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014:311:1870–1882.

[5] Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D et al. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2014:63:2541–2548.

[6] Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M et al. A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014:370:1809–1819.

[7] Raal FJ, Stein EA, Dufour R et al. PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab (AMG 145) in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (RUTHERFORD-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015:385:331–340.

[8] Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1501031.

[9] Dimise EJ. AHA Scientific Sessions 2014: Where do the PCSK9s fit in the post IMPROVE-IT world? A “modest” proposal. Formulary Watch, 5 December 2014.

[10] Patel J, Sheehan V & Gurk-Turner C. Ezetimibe (Zetia): a new type of lipid-lowering agent. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center) 2003;16:354–358.

[11] Kastelein JJ, Akdim F, Stroes ES et al. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. The New England Journal of Medicine 2008:358:1431–1443.

[12] Beasley D. Pfizer developing PCSK9 pill, vaccine to lower cholesterol . Reuters, 13 January 2015.

[13] Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD et al. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500858.