Courtesy of PharmacyHealthLink materials

This content was published in 2007. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Although the discipline and concept of public health is not new to pharmacy — there are, after all, national strategies to develop pharmaceutical public health in England and Scotland (see Panel 1) — it appears that a significant number of pharmacists remain either sceptical or uninspired about its relevance to pharmacy practice. In part this is due to the use of language that does not sit easily with those trained principally in the pure or applied sciences. For example, the most commonly cited and widely accepted definition of public health is “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organised efforts of society”.1 This definition, coined by Donald Acheson, clearly has non-traditional scientific aims, making reference to “the science and art of ” and to the equally nebulous term “society”. Acheson’s definition is not shy about engaging with non-traditional scientific disciplines and refers to human resources as agents of change. To understand public health in this way requires an initial understanding and acceptance of the wider role of the arts, humanities, and the social and behavioural sciences — alongside the pure and applied sciences — in achieving a common good. Therefore, given its complexity, perhaps it is unsurprising that public health has been described as a vague, aspirational concept. Nobody wants publicly to demean its value because there is broad acceptance of it as an “intrinsically good thing”. However, by being beyond the usual boundaries of challenge, public health also risks losing impact and meaning. So is public health merely an abstract good idea, or are there more tangible, meaningful components to it with which pharmacy can usefully engage?

Panel 1: Strategies for pharmaceutical public health in England, Scotland and Wales

England “Choosing health through pharmacy. A programme for pharmaceutical public health 2005–2015” was published by the Department of Health (England) in 2005 (www.dh.gov.uk/ publications). The English strategy acknowledges the contribution already made to public health by pharmacists and their staff working in a variety of settings, and sets out how they can help deliver the health improvement strategy “Choosing health”. It also outlines a vision of how pharmaceutical public health might look in 2015 should the actions identified in the strategy be delivered.

Scotland “Pharmacy for health: the way forward for pharmaceutical public health in Scotland” was published in January 2003 by the Public Health Institute of Scotland (www.phis.org.uk/pdf. pl?file=publications/Pharmacy.pdf). This document highlights the main areas where pharmacists have already made a contribution to public health and how they might further contribute to the health improvement aims of “The right medicine: a strategy for pharmaceutical care in Scotland”(PJ, 8 February 2003, pp197–200).

Wales Wales does not have a specific public health pharmacy strategy at present.

Population perspective

The easiest way to conceptualise what public health means in practice is to understand the “population perspective”. There are many different definitions of public health (see Panel 2) but, collectively, the defining feature of them is the emphasis they place on activities focused above an individual level. Whether they refer to a strategic or population approach to optimise use of resources or health gain, or emphasise the processes or structures through which health gain is achieved, they all, ultimately, focus on the benefits to society, communities or groups rather than on individuals (on whom most health professionals focus their time and resources). Simple examples of public health measures include ensuring a clean water supply, running vaccination programmes and distributing free condoms.

Panel 2: Definitions

Adaptations of Acheson’s definition of public health are commonly used, some examples follow:

Public health Derek Wanless, in “Securing good health for the whole population” (www.hmtreasury. gov.uk/wanless added that “informed choices of society” is a facet of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health.

Pharmaceutical public health Pharmaceutical public health has been described as “the application of pharmaceutical knowledge, skills and resources to the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, promoting, protecting and improving health for all through organised efforts of society”.2

Some organisations adopt an action-oriented view of public health. For example, the UK Public Health Association, describes public health as an approach that:3

- Focuses on the health and well being of a society and the most effective means of protecting and improving it

- Encompasses the science, art and politics of preventing illness and disease and promoting health and well being

- Addresses the root causes of illness and disease, including the interacting social, environmental, biological and psychological dimensions, as well as the provision of effective health services

- Addresses inequalities, injustices and denials of human rights, which frequently explain large variations in health locally, nationally and globally

- Works effectively through partnerships that cut across professional and organisational boundaries and seeks to eliminate avoidable distinctions

- Relies on evidence, judgement and skills and promotes the participation of the populations who are themselves

The approach uses multidisciplinary research based on a scientific method, typically going beyond the biological and clinical sciences to include social and behavioural science approaches. Research conducted on the health needs of various populations is used to mobilise resources to improve health and reduce inequalities in health. In England, this has led to changes to the pharmacy contractual framework (eg, providing brief advice on lifestyle issues is an essential service) and incentives for some pharmacy services (eg, enhanced services).

Wider determinants of health

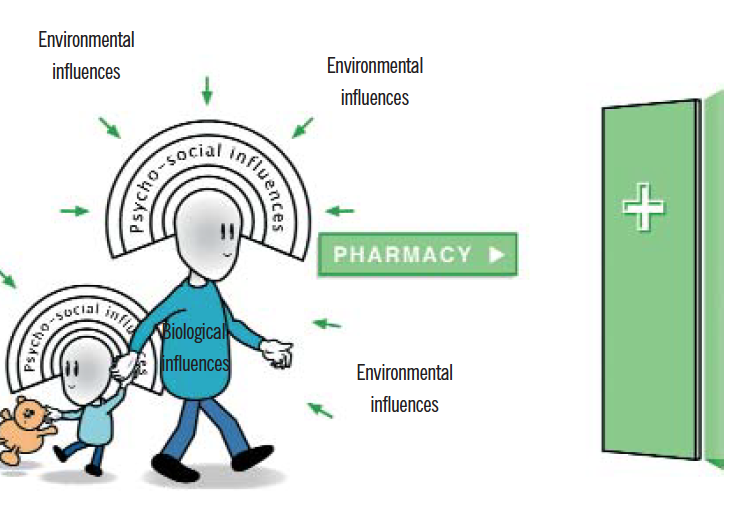

In tandem with the population approach is the need to examine and influence the distribution of health and health gain within a specified population. Invariably, this endeavour will require some knowledge and understanding of the wider determinants of health and how they influence all levels of society — at a global, national, regional, local community, group and individual level. These include environmental influences, psycho-social influences and biological influences over time. In addition, individuals possess some power to influence their environment (although there is plenty of individual variation), and can use their personal (and other) resources to interact with their wider environment to optimise their own well-being.

Clearly this is a complex scenario and most models that are used to illustrate these concepts risk losing, or over-simplifying, the essential influences on human behaviour (some of which might be subtle, but still have a profound influence, particularly in the long term) and health outcomes, and the interactions between them. These wider determinants of health are relevant to pharmacy practice and have a significant influence on outcomes, such as adherence. As everyone in pharmacy is aware, millions of pounds are not dedicated to the research and development and distribution of medicines for the sake of production alone. Medicines have a high value in society principally because they affect health outcomes for the better (in the vast majority of cases), however, their benefits are highly influenced by individual and societal variations — not only through genetic or physiological factors, but also by psycho-social factors (operating proximally or distally). At the very least, practising pharmacists should be able to recognise how some psycho-social factors (eg, depression and unemployment) might affect health outcomes.

Public health in pharmacy practice

Aside from the theory and philosophy underpinning public health, there are some much more grounded aspects of practice that pharmacists can relate to on a day-to-day level.

The most widely accepted functional division of public health practice in the UK is based on the three domains identified by the Faculty of Public Health as:

- Health and social care (service quality)

- Health protection and prevention

- Health improvement

These activities are principally NHSfocused, and some would argue that they do not sufficiently reflect the wider environmental aspects of public health (such as sustainable development and environmentally friendly policies). Pharmacy already contributes to each of these areas via its NHS services but it is the general aim of UK national health policies to increase and refine the pharmacy contribution in all three areas, although the emphasis might vary. The main areas of pharmacy practice governed by each domain, with examples, are listed in Panel 3.

Panel 3: The three main domains identified by the Faculty of Public Health

Health and social care

- Quality

- Clinical effectiveness

- Efficiency

- Service planning

- Audit and evaluation

- Clinical governance

These activities are familiar to most pharmacists and largely considered integral to good pharmacy practice.

Health protection and prevention

- Disease and injury prevention (eg, ensuring medicines are taken correctly, advising on storage in the home)

- Communicable disease control (eg, reporting notifiable diseases, opportunistic screening, such as for chlamydia, and identification of key groups for vaccinations)

- Environmental health (ie, safe standards for air, water, food; eg, ensuring safe disposal of medicines and medical devices)

- Emergency planning (eg, a role in containing a pandemic influenza outbreak)

At present, most pharmacists take part in these activities in diverse ways but their contribution may not be formally recognised and — as a result of this informal participation — the approach they use may not be systematic (ie, they will identify some “cases” but not all). In future, it is envisaged that community pharmacists will receive support for their wider and systematic participation in health protection activities.

Health improvement

- Employment (eg, employing local staff, especially those with knowledge of cultural differences for local ethnic groups or also are bilingual)

- Housing (eg, reporting problems such as an older person needing bathroom handrails on home visits)

- Family or community (eg, promoting uptake of vaccines)

- Education (eg, talking to schools on health topics)

- Inequalities or exclusion

- Lifestyles (eg, advising on stopping smoking)

In the UK, health improvement can be focused on the individual (eg, a one-to-one discussion between the pharmacist and the person concerned, or their carer) or efforts can be focused at improving the health of the local community (eg, talking to school pupils, parents and teachers about head lice or sexual health and contraception)

Is it worthwhile?

Generally speaking, although some good evidence exists for the contribution that community pharmacy can make to improving health, when compared with other disciplines (eg, general medical practice and nursing), the research carried out primarily as a public health endeavour in pharmacy is limited. The most conspicous example of this was borne out during the recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence review of brief interventions in smoking cessation, where over 17 studies were identified and reviewed from general practice and six from nursing.

In contrast, there was simply no evidence identified by the same search strategy from the pharmacy sector and the authors concluded:“ There has been no research on brief interventions [on smoking cessation] delivered by pharmacists.” Of course this is not to deny that pharmacy interventions already do, or can, contribute significantly to public health (directly or indirectly). Instead, it perhaps reflects the prevailing focus on research on medicines and treatments rather than the broader health-related outcomes of pharmacy interventions. Indeed, the current consultation on the future undergraduate pharmacy curriculum seems to be holding to the former approach, whereas Pharmacy HealthLink believes the profession needs to move far closer to the latter.

Conclusion

There are many aspects of pharmacy practice that are relevant to public health and that could contribute directly to actual health gain, or indirectly through better information gathering and use of information systems to inform decision-making. Undoubtedly pharmacy could contribute much more than it does at present, and it is the aims of both of the national strategies (see Panel 1) to deliver this vision. However, it is clear that a few years after publication of the strategies, much more needs to happen and perhaps it is time for the profession to have a much more thorough debate. The current consultation on the future undergraduate pharmacy curriculum seems an ideal place to start the discussion.

References

- Acheson D. Public health in England: report of the Committee of Inquiry into the future development of the public health function. Department of Health: London; 1988.

- Walker, R. Pharmaceutical public health: the end of pharmaceutical care? The Pharmaceutical Journal 2000;264:340–1.

- UK Public Health Assocation. UKPHA definition of public health. Available at: www.ukpha.org.uk (accessed 21 December 2006).

- PharmacyHealthLink response to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Fit for the Future: Principles of Pharmacy Education and Training Consultation. Available at: www.pharmacyhealthlink.org.uk (accessed 21 December 2006).