Emily Nash

Insomnia is like waiting at a bus stop, says Kevin Morgan, director of the Clinical Sleep Research Unit at Loughborough University, UK. After a while, you start to think the bus should have arrived by now, and you have to make a decision — do you walk away or simply wait?

The latter is what people do when they cannot sleep, he says. “They wait for it to come, thinking, ‘if I get out of bed, I’ll miss it, so I should probably stay here’.”

As a result, these individuals lose the learned association between going to bed and going to sleep, which many of us take for granted.

As people age, their sleep patterns can also undergo a number of changes. They may find it even more difficult to fall asleep or may sleep a lot less than they used to and wake up earlier than they want to. Sleep research is growing, but it is still in its infancy; researchers are investigating why sleep changes as people age, the health implications of not getting enough sleep, and the sleep hygiene habits we should all take on.

Insomnia

The most common of the sleep disorders, insomnia, is defined as a persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, or quality, which occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep, and results in some form of daytime impairment. It is diagnosed on the basis of this difficulty occurring at least three times a week and having been present for at least the previous three months.

Insomnia is different to sleep deprivation, which occurs as a result of short sleep and leads to sleepiness and an increased propensity to fall asleep. Individuals with insomnia tend to feel fatigue but they do not feel sleepy. The estimated prevalence of insomnia is 8–12% for adults, and an estimated 30–50% of the population will experience some insomnia symptoms at some point in their lives.

In the UK, insomnia rates show a steady rise as age increases. According to Morgan, the prevalence of insomnia in mid-life is around 10%, while in later life, it rises to around 20–25%. As a result, he says, people tend to link insomnia to getting older but, in reality, it is much more complicated than that.

“Once insomnia becomes embedded in an individual’s personal history, it tends to stay there,” he says.

Once insomnia becomes embedded in an individual’s personal history, it tends to stay there

“Anything that is chronic, irreversible and can arrive at any age, accumulates in older age,” much like baldness, he adds.

“Men can become bald at almost any decade but if you look at [older] men, 50% are bald. It doesn’t mean it’s to do with being old — it’s because it’s chronic and irreversible.”

Insomnia is the product of three ingredients: predisposing factors, precipitating events and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors refer to a particular type of psychological configuration that makes individuals vulnerable to insomnia. “This is characterised by an inability to disconnect from a focus on some highly specific things, and in terms of insomnia you focus on not going to sleep,” explains Morgan.

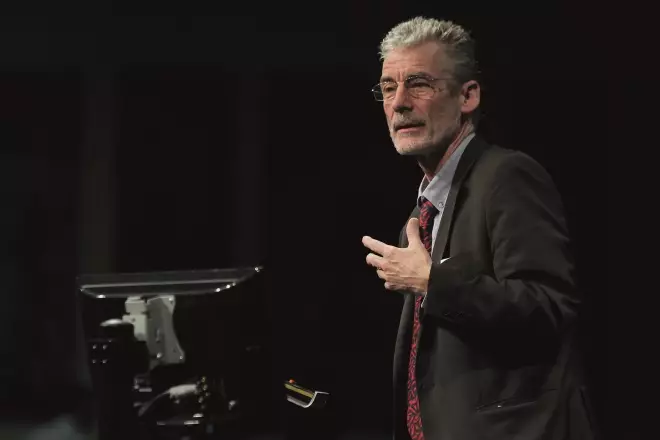

Source: Courtesy of Kevin Morgan

Kevin Morgan, director of the Clinical Sleep Research Unit at Loughborough University, says that people tend to link insomnia to getting older but, in reality, it is much more complicated than that

“You lock into a vicious cycle — I’m not asleep, that makes me concerned, my concern transfers into an effort to go to sleep, the effort to go to sleep generates the very level of alertness that stops sleep — some people are predisposed to that style of thinking.”

Some people who are predisposed may never experience an event that precipitates insomnia, for example, a personal trauma, illness or life event. However, later life, Morgan says, can have its “own minefield of precipitating events”.

For example, for women, the menopause, with its hormonal changes, hot flushes, thermoregulation problems and sleep disturbances, can have a huge impact on sleep quality and quantity. Later life is also associated with a higher probability of chronic conditions and pain, which can also disturb sleep.

The final piece of the puzzle required for an individual to lock into an “insomnia career”, as Morgan refers to it, is perpetuating factors. “These tend to be behavioural and cognitive — things that people do and styles of thinking that people adopt,” he says.

“If you repeatedly and habitually go to your bed wondering if tonight is going to be the night when you get a good night’s sleep, you take into your bed a preprogrammed expectation that sleep might not happen. No one who sleeps well does this.”

If you go to your bed wondering if you’ll get a good night’s sleep, you take into your bed a preprogrammed expectation that sleep might not happen

Sleep and ageing

Contrary to popular belief, the idea that we need less sleep as we get older is a fallacy, according to James Goodwin, chief scientist at Age UK.

The Global Council for Brain Health, of which Goodwin is a member, says that your need for sleep remains the same throughout your life — between 7 and 8 hours in every 24.

“These are measured words — not 7–8 hours at night — 7–8 hours in a 24-hour period, right the way through your life,” he says.

The change is that, unfortunately, it becomes less easy for older adults to generate the restorative sleep they require.

According to Matthew Walker, neuroscientist and sleep expert at the University of California, Berkeley, three key changes happen in our sleep as we get older: quantity and quality are reduced; sleep becomes less efficient; and the timing of sleep is disrupted.

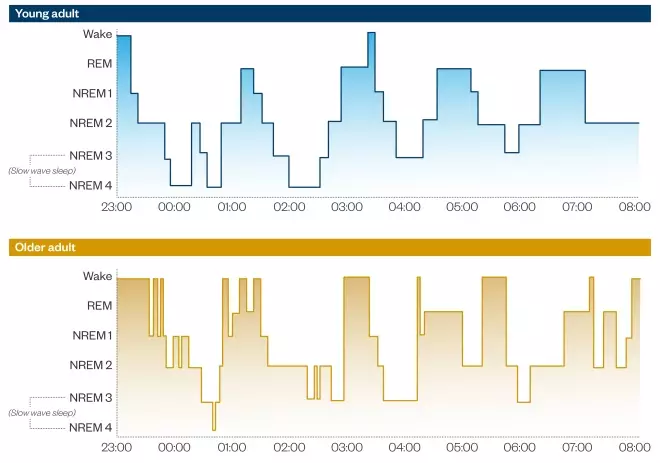

In his book ‘Why we sleep’, Walker says that by the time we reach 70 years of age, we will have lost 80–90% of deep (stage 3 and 4, or slow wave) non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, meaning we have fewer hours of the deepest stages of sleep. This gradual reduction in deep NREM starts happening as early as our late 20s (see Figure 1)[1]

.

“Ageing is associated with decreases in the amount of slow wave sleep and increases in stage one and two non-rapid eye movement sleep, often attributed to an increased number of spontaneous arousals that occur in [older people],” explains Ari Manuel, a sleep ventilation consultant at Aintree University Hospital Trust, UK.

As we get older, our auditory awakening thresholds also reduce, despite our hearing acuity diminishing, meaning that it becomes easier to wake an older person with noise, regardless of the sleep stage they are in.

Figure 1: The human sleep cycle in young and older adults

Source: Mander B, Winer J & Walker M. Sleep and human aging. Neuron 2017;94:19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.004

Humans cycle through two types of sleep which differ in terms of brainwave activity, eye movement activity and muscle activity — rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is characterised by rapid movement of the eyes and dreaming, and deeper, non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, in which there is no dreaming. REM and NREM alternate within one sleep cycle, which lasts about 90 minutes in adults.

NREM is further subdivided into four separate stages, which increase in depth. Stages 3 and 4 are the deepest stages of NREM sleep.

As we age, the amount of stage 3 and 4 NREM sleep gradually reduces, meaning we get fewer hours of the deepest stages of sleep.

Sleep in older people is also altered by increased waking throughout the night as a result of interacting medicines and diseases, but mainly resulting from a weakened bladder requiring more frequent visits to the toilet.

Increasing numbers of studies have described the negative effect of nocturia — going to the toilet once or more during the night — on sleep quality. One study found that the severity of nocturia increased with age in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, and was significantly correlated with poor sleep quality, daytime dysfunction and in some cases, higher rates of sleeping pill use[2]

.

Furthermore, sleep-related respiratory disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, occur with increasing prevalence in older people and can further disrupt sleep patterns.

Out of rhythm

Finally, sleep change in advanced age is related to changes in our circadian rhythms.

“[Older] individuals tend to go to sleep earlier in the evening and wake earlier due to a phase advance in their normal circadian sleep cycle,” says Manuel, who works at a tertiary sleep unit.

Older individuals tend to go to sleep earlier in the evening and wake earlier due to a phase advance in their normal circadian sleep cycle

As we enter old age, a regression in our circadian rhythm causes an earlier evening release and peak of melatonin, which prompts an earlier start time for sleep[3]

. This trigger for an early-evening doze clears away the sleep pressure of an enzyme called adenosine, which steadily builds during the day causing us to get sleepy in the evening.

As a result, when that individual eventually goes to bed, they may find it difficult to fall asleep or to stay asleep. Their melatonin levels will then continue to fall until around 04:00–05:00 when production is shut off altogether, signalling the end of sleep and causing the individual to wake much earlier than they would like.

This pattern may contribute to daytime fatigue and napping, with a consequential negative impact on next-day functioning. Excessive daytime napping can also result in poor-quality sleep and reduced sleep quantity at night.

According to Goodwin, alterations in our sleeping patterns as we age are the result of holistic changes in the ageing process. These include generalised cognitive decline and neuronal loss in the brain, but also changes to circumstantial factors, including social connectivity, diet, hydration, mental wellbeing, health and housing.

Source: Courtesy of James Goodwin

James Goodwin, chief scientist at Age UK, says that a better appreciation is needed of the crucial importance of sleep in generating good health and wellbeing in older age

Long-term health conditions, such as stroke, hypertension and diabetes, which occur more frequently in older people, are also associated with poor sleep quality. Studies have shown that, after controlling for comorbidities, the rates of insomnia reported in the older population fall significantly.

“It’s crucial to understand that sleep is the absolute confluence of physical, environmental, genetic and psychological factors, which is a little bit different to many areas of medicine,” explains Guy Leschziner, clinical lead of the sleep disorders centre at Guy’s Hospital in London — one of the largest in the UK.

Health consequences

In his clinic, Leschziner and his team of consultants, psychologists and pharmacists, see around 14,000 patients a year.

He explains that the health consequences of poor sleep are continuing to emerge as sleep research grows. So far, it has been linked to weight gain, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and a disturbing number of other health issues[4]

.

According to Walker’s book, there have been more than 20 large-scale epidemiological studies that have tracked millions of people over many decades — all of which report the same clear relationship: the shorter your sleep, the shorter your life[5]

.

We know that poor sleep gives rise to anxiety, depression and cognitive complaints. In people with dementia, when we improve their sleep, sometimes their functioning improves as well

In addition, he says that adults aged 45 years or older who sleep fewer than 6 hours a night are 200% more likely to have a heart attack or stroke during their lifetime, compared with those sleeping 7–8 hours a night.

Another study found that losing just one night of sleep resulted in an immediate increase in beta-amyloid, a protein in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease[6]

.

“We know that poor sleep gives rise to anxiety, depression and cognitive complaints. In people with dementia, when we improve their sleep, sometimes their functioning improves as well,” says Leschziner.

A lack of sleep has also been linked to cancer. In 2007, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified shift work with circadian disruption or ‘chronodisruption’ as a probable human carcinogen.

Sleep is also necessary to maintain the efficiency of our immune systems and studies have shown that if you sleep deprive people for a long time they eventually become immunocompromised[7]

.

In addition, there are many mental health issues that can arise in those who do not get enough sleep. One of the most thoroughly researched consequences of chronic insomnia is that the risk of major depression is hugely increased, relative to people who sleep well, says Morgan[8]

,[9]

.

Caroline Horton is director of DrEAMSLab (Dreams, Emotions, Associations and Memories in Sleep Lab), which explores sleep-related cognition and is based at Bishop Grosseteste University in Lincoln. She says that every mental health diagnosis will include a diagnosis of poor sleep, disrupted sleep, difficulty falling asleep or difficulty staying asleep.

Source: Courtesy of Caroline Horton

Caroline Horton, director of DrEAMSLab at Bishop Grosseteste University in Lincoln, explains that if you decrease the amount of sleep you normally have, over time, your ability to think clearly and to be able to assess memories accurately, slows down

If an individual has a tendency towards depression, or if something has happened in their life that they are struggling to process, it is likely that they will sleep poorly, she explains. Sleeping poorly will then impact negatively on the way that they deal with their depression or life event, and consequently sleep will become even more of a struggle.

“There’s a really complex ongoing relationship between sleep and mood, anxiety and psychiatric disorders — and that’s just the psychological side,” she says.

However, it’s not only the long-term consequences we should be concerned about, the short-term consequences of sleep loss are also significant.

Horton explains that it is possible to demonstrate that if you decrease the amount of sleep you normally have, over time, your ability to think clearly and to be able to assess memories accurately, slows down.

“Your ability to learn new information is vastly impaired. Coupled with that, you will have a bias towards negative stimuli so, if you don’t have enough sleep, you wake up, see something that’s probably neutral, but you see it as a negative threat,” she says.

“We’re also clumsier, we forget words, our concentration and ability to sustain attention on single things are impaired and our ability to remain aroused is impaired,” says Morgan.

“We need sleep — it’s so crucial — it might seem like an inconvenience, but we absolutely cannot function without it,” concludes Horton.

A light at the end of the tunnel

A better appreciation of the crucial importance of sleep in generating good health and wellbeing in older age is needed, according to Goodwin.

“It is only just beginning to assume the importance it should have,” he says.

Having a good knowledge of how lifestyle behaviour can improve sleep is exceptionally useful for a pharmacist — patients need a good dose of behavioural modification before you get to the stage where you are dispensing pharmaceuticals

“We know that the risk of poor health is greatly increased by an absence of sleep and we know that cognition … is also greatly impacted on by the absence of sleep.

“It’s the maintenance of good cognitive function that enables individuals to remain autonomous and independent,” he adds.

Goodwin highlights, while changes in sleep as we age can be expected, they can also be reasonably managed and most older people should be able to achieve good sleep.

In terms of the role that pharmacists can play, he says that they can do a lot by simply talking to their patients and finding out more about their sleep patterns.

“Having a good knowledge of how lifestyle behaviour can improve sleep is exceptionally useful for a pharmacist — patients need a good dose of behavioural modification before you get to the stage where you are dispensing pharmaceuticals.”

Elaine Lyons, a pharmacist specialising in sleep and respiratory medicine, who works alongside Leschziner at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ sleep disorders centre, runs the only pharmacist-led titration clinics in sleep medicine in the UK, and she says that her list of patients is “spiralling”.

Source: Courtesy of Elaine Lyons

Elaine Lyons, a pharmacist specialising in sleep and respiratory medicine, emphasises the need for the development of agents that target both sleep initiation and sleep maintenance without residual next-day effects

The clinic sees patients aged from 16–100 years old and Lyons says that sleep disturbances are a common complaint among those aged 65 years and older.

Most treatment guidelines recommend non-pharmacological approaches to managing sleep complaints, including improved sleep hygiene (see Panel 1) and behavioural therapy techniques, such as cognitive behavioural therapy.

Panel 1: Sleep hygiene – ten tips for a good night’s sleep

- Amount: aim for 7–8 hours’ sleep in every 24 hours.

- Routine: get up at the same time every day and maintain a regular routine in preparation for bedtime – for example take a warm bath, avoid blue light, etc.

- Environment: keep the bedroom quiet and dark. If you have to get up, use soft lighting. Maintain a comfortable room temperature. Keep smartphones, books and electronics out of the bedroom.

- Exercise: regular physical activity promotes good sleep, but avoid strenuous exercise at least two hours before bedtime.

- Food: restrict fluids and food three hours before going to bed.

- Alcohol: avoid alcohol several hours before bedtime — it can take 2–3 hours for your body to eliminate it.

- Caffeine: do not drink caffeine after 14:00.

- Smoking: avoid smoking and nicotine substances 4–6 hours before bed.

- Medication: avoid using over-the-counter medicines for sleep because they can have negative side-effects (see Panel 2). Dietary supplements, such as melatonin, may have benefits for some, but the scientific evidence on their effectiveness is inconclusive. If you are using prescription medicines to help you sleep, consider limiting their use to three nights a week as habitual use can limit their effectiveness, unless your health provider says otherwise.

- Pets: keep pets that disturb sleep out of the bedroom.

Source: Global Council on Brain Health: Recommendations on sleep and brain health and Age UK

According to Lyons, the most common pharmacological treatments for sleep are benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepines (‘Z-drugs’ such as zopiclone and zolpidem), antidepressants and over-the-counter sedating antihistamines (see Table 1). Most of these, she says, have a negative impact on next-day functioning and increase the risk of falls.

“We run into several problems with most sleeping aids, such as interactions with other centrally acting medication, but also dependence and subsequent withdrawal symptoms from the individual agent if stopped abruptly,” she explains.

Dependence can develop with centrally acting drugs, such as benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Pharmacists should flag vulnerable individuals at risk of substance misuse or dependence for medication reviews, says Lyons.

She emphasises the need for the development of agents that target both sleep initiation and sleep maintenance without residual next-day effects.

“I have no doubt that improving next-day functioning would have a positive impact on both patients and their carers,” she says.

It is clear that everyone should pay a great deal of attention to their sleep. Much the same as diet and exercise are recommended for a healthy lifestyle, sleep too should be actively promoted, incentivised and, in some cases, prescribed.

So for those who spend their twilight hours waiting at the proverbial bus stop, all is not lost. With the right help and behavioural changes, it is possible to regain control over the sleep timetable.

| Product | Manufacturer | Ingredients | Possible side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: PAGB OTC Directory Online, summaries of product characteristics | |||

| Nytol Original | Omega Pharma UK | Diphenhydramine hydrochloride 25mg | Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, stomach upset, blurred vision, dry mouth |

| Nytol One-A-Night | Omega Pharma UK | Diphenhydramine hydrochloride 50mg | Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, stomach upset, blurred vision, dry mouth |

| Nytol Herbal Simply Sleep One-A-Night | Omega Pharma UK | Valerian root extract 385mg | Nausea, abdominal cramps |

| Nytol Herbal Tablets | Omega Pharma UK | Hop strobile extract 34mg/Valerian root extract 30.8mg/Passion flower herb extract 15.2mg | Nausea, abdominal cramps |

| Kalms Night | G R Lane Health Products | Valerian root extract 96mg | Nausea, abdominal cramps |

| Phenergan | Sominex | Promethazine 10mg or 25mg | Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, blurred vision, dry mouth, weight gain |

| Potter’s Nodoff Plus Mixture | Soho Flordis UK | Passion flower extract 0.5mL/Jamaica dogwood bark extract 0.5mL/Hop strobile extract 0.4mL/Valerian root extract 0.25mL | Nausea, abdominal cramps |

| Sominex Herbal | Teva UK | Passion flower extract 130mg/Hop strobile extract 200mg/Valerian root extract 160mg | Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, stomach upset, blurred vision, dry mouth |

| Kira Restful Sleep | Klosterfrau Healthcare Group | Valerian root extract 300mg | Nausea, abdominal cramps, drowsiness |

References

[1] Walker M. Why we sleep: The new science of sleep and dreams. London: Penguin Random House; 2017, p96

[2] Shao IH, Wu CC, Hsu HS et al. The effect of nocturia on sleep quality and daytime function in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: a cross-sectional study. Clin Interv Aging 2016;11:879-885. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S104634

[3] Walker M. Why we sleep: The new science of sleep and dreams. London: Penguin Random House; 2017, p98

[4] Tochikubo O, Ikeda A, Miyajima E et al. Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure monitored by a new multi-biomedical recorder. Hyperten 1996;27:1318–1324. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.27.6.1318

[5] Walker M. Why we sleep: The new science of sleep and dreams. London: Penguin Random House; 2017, p164

[6] Shokri-Kojori E, Wang G-J, Wiers C et al.  β-Amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation.  PNAS 2018;115:4483–4488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721694115

[7] Watson N, Buchwald D, Delrow J et al.  Transcriptional signatures of sleep duration discordance in monozygotic twins.  Sleep 2017;40:zsw019. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw019

[8] Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Dis 2011;135:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

[9] Riemann D & Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression. J Affect Dis 2003;76:255–259. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00072-1