NIPH

The executive director of infection control and environmental health at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, John-Arne Røttingen, has worked in public health since 1999. Since 2012, he has also been teaching at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston. Røttingen has been instrumental in establishing and running an Ebola vaccine trial in Guinea, which has won respect both in terms of speed and results. In less than a year the preliminary results show 100% efficacy.

How and when did it all start?

The World Health Organization (WHO) organised a high-level meeting on Ebola vaccines on 23 October 2014. At that stage, two larger trials were planned for Liberia and Sierra Leone led by the US National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, respectively, but there were no specific plans for Guinea. Representatives from Guinea expressed that they also wanted to contribute to, as well as benefit from, vaccine testing. As a result, an open working group on Ebola vaccine trials in Guinea was formed that afternoon. We then had our first full-day meeting on 5 November 2015 in Geneva, Switzerland, where more detailed plans were made by a wide group of institutions and participants.

Vaccine developments usually take ten years. Your team did it in less than a year (preliminary results). What are the main three reasons why this was possible?

There have been several teams contributing to this extremely speedy clinical testing of Ebola vaccines. Several teams started phase I trials in Europe, the United States and Africa from September 2014, and then other teams planned for larger phase II trials in African countries not struck by the Ebola epidemic. Our team for the phase III trial in Guinea constituted of Guinea, WHO, Médecins Sans Frontières and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), as well as several academic institutions. It is the totality of teams and partners that is the main reason for the robust and solid clinical testing process. However, without expedite funding decisions and reviews and assessments from regulatory and ethical review processes, this would not have been possible. Finally, promising vaccine candidates were available and the pharmaceutical companies that owned them demonstrated a clear willingness to precede with other opportunities to make Ebola a priority.

What is the ring approach to conducting the trial and why was it used?

Ring vaccination has been used as a public health measure when stamping out the last pockets of smallpox during the eradication campaign. It is a “forest fire” strategy where contacts of cases and their contacts again are vaccinated to stop further transmission to a wider population group. However, it has never been used in a vaccine trial. Our rationale for doing so was a combination of wanting to do a pragmatic trial where the most likely strategy for utilisation of an Ebola vaccine was tested and, at the same time, needing to do the testing among high-risk groups where Ebola-transmission occurred.

What are the side effects and safety profile of the vaccine?

So far, the side effects are minor and in line with what is to be expected of a live vaccine, but more detailed and longer follow up will be reported. Some of the phase I trials picked up arthritis as a temporary side effect, but this does not seem to be the case in the larger studies in Africa. We are waiting to see the safety data from other parallel trials. We will also do a full analysis of our data when the trial is completed in early 2016.

The trial is ongoing. What’s next?

Yes, the trial continues, but without the control arm from August 2015. We saw that it would be important to collect more data on the vaccine and, at the same time, secure access to the vaccine through ring vaccination around new cases in Guinea and also later in Sierra Leone. Now we are planning for closure of the trial because there have been no reported cases of Ebola from Guinea in several consecutive weeks. However, all included volunteers will need to be followed up for the full period first.

When can we see a potential rollout?

The next step is to make our data and data from other trials ready for assessment by regulatory agencies. Merck will submit an application for regulatory approval, and then the regulatory authorities will make their decisions probably around mid-2016. The vaccine will be accessible in this interim period through an extended access scheme, but it is not until formal approval that the vaccine will be licensed for use. This vaccine will not be considered a mass vaccine, though, and will probably be used for ring vaccination, as well as vaccination of health personnel and other front line workers at risk.

The vaccine was not tested widely on children, adolescents, and pregnant and breastfeeding women. What can be done to protect these groups of people from Ebola?

Smaller trials on adolescents and children have been conducted, and there will hopefully be sufficient safety data to include these groups when the vaccines are considered for approval. We decided to include older children late in our trial when the safety data indicated a good profile among children. Risk-benefit assessments for using the vaccine for pregnant women will also be conducted.

Does this vaccine provide long-term or life-long protection?

We do not know the length of protection. We and others will assess antibody responses after longer follow up, but it is too early to say what duration of response we will see — and what will indicate protection.

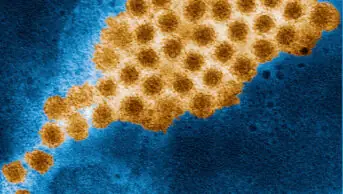

Why is this a ‘rVSV-vectored’ Ebola vaccine and what is the advantages of this?

This Ebola vaccine is a recombinant vaccine where the gene for a glycoprotein of the Ebola virus is substituted for a normal gene of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). The VSV thereby acts as a vector that helps transfer the antigen for the detection and response by the immune system.

Based on the Ebola outbreak, you have called for a global system for research and development (R&D) preparedness and response for pandemics, such as an R&D fund of at least US$1bn. How would it work and when can we expect to see it?

The WHO Ebola Research and Development summit in May 2015 called for a blueprint on R&D to be better prepared for future outbreaks and epidemics. This blueprint is now being developed through a larger consultation process with several meetings. A global R&D financing mechanism that can be used for preparation, as well as during a crisis, will be necessary to implement such a blueprint. The world does not want — and does not need — to see another Ebola outbreak of this magnitude and its devastating effects. There are now several evaluations and panels that have concluded on the need for an R&D financing and co-ordination mechanism, and I hope that heads of states will make decisions in this direction at some stage in 2016.

What will be the patent situation of this vaccine and will people who are affected be able to afford it?

The VSV vaccine is patented by the Canadian Public Health Agency, and Merck has the exclusive licence for the vaccine. It is obvious that there is no commercial market for an Ebola vaccine, and therefore there needs to be established a stockpiling mechanism funded by public and philanthropic sources to secure access during future outbreaks.

What is the overall lesson learnt from this Ebola project?

We have witnessed a co-ordinated and managed vaccine trial system that, through international collaboration and sharing of knowledge and early results, has delivered a collective good. Competition is key both for industry and academic research, but managed collaboration in the midst of a crisis is necessary. In such circumstances, collective results should be seen as indicators of success and much more important than results from each independent actor.

You may also be interested in

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control