Shutterstock.com/MAG

Repeated warnings of an antibiotic apocalypse appear to be having an impact in general and dental practice, where antibiotic consumption has decreased by 17.3% and 26.8%, respectively, since 2014. However, it is a different story in secondary care, where antibiotic use has increased by 2.8% over the past five years[1]

.

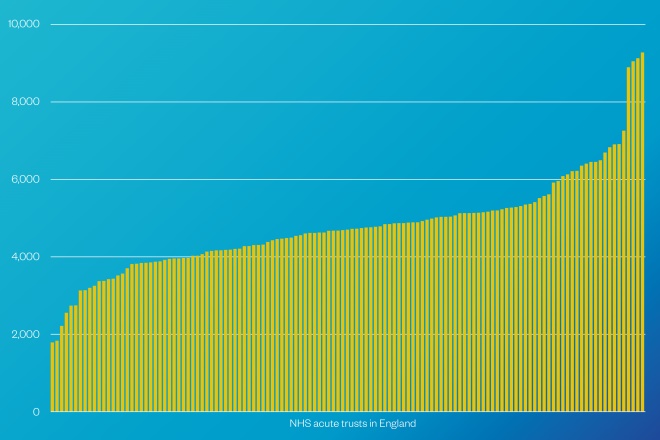

Most trusts in the country still have a long way to go to achieve a consistent reduction in their antibiotic consumption, but some hospitals are bucking the trend. In 2018/2019, antibiotic consumption in acute trusts in England ranged from 1,782.1 defined daily doses (DDDs) of antibiotics dispensed to all inpatients and outpatients per 1,000 admissions, to 9,217.1 DDDs per 1,000 admissions, according to data collected by The Pharmaceutical Journal from Public Health England’s ‘Fingertips’ database (see Graph)[2]

. DDDs are a statistical measure of drug consumption used to standardise comparisons between different medicines and healthcare settings.

Almost 50% of these trusts achieved a decrease in this measure between 2017/2018 and 2018/2019, ranging from 0.2% to 57.6%, with 14 out of 155 trusts achieving a reduction of 10% or more.

Hospitals are using a variety of strategies to achieve antimicrobial resistance (AMR) targets under the ‘Commissioning for Quality and Innovation’ financial incentive scheme (see Box)[3]

. Some trusts were reluctant to discuss their approaches with The Pharmaceutical Journal before being sure they could maintain their decline in consumption, but others shared some of the secrets of their success.

Graph: Defined daily dose of antibiotics dispensed by acute trust pharmacies to all inpatients and outpatients per 1,000 admissions in 2018/2019

Source: Public Health England

1. Embrace technology

The ‘MicroGuide’ smartphone app was developed to enable pharmacists to create, edit and publish antimicrobial guidelines to their clinicians’ mobile devices so they always have access to the latest guidance at the point of care.

Abiodun Ogundana, lead antimicrobial and nutrition pharmacist at Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, says the app has been invaluable in ensuring teams in the hospital comply with antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) in terms of treatment and duration. The trust achieved an 18.9% reduction in overall antibiotic use between 2017/2018 and 2018/2019, and has consistently reduced its consumption since 2016.

“We decided that we wanted our guidelines [accessed via the app] to be more detailed … with first-line treatment, second-line treatment, duration and as many indications as possible to help the doctors to make the right choice of treatment, and to know how long patients should be on antibiotics for,” says Ogundana.

Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH) NHS Foundation Trust, which has achieved a reduction in antibiotics dispensed for the past three years running, and a 57.7% reduction since 2014/2015, has long championed the use of IT to improve AMS.

“The introduction of our electronic patient record system, called Epic, is a significant example of that,” explains Reem Santos, lead antimicrobial pharmacist at CUH.

“Epic enables clinicians to more accurately record antibiotic use, and provides immediate access to patient information and clinical decision support to ensure patients receive the most appropriate medication at the optimal dose and duration.”

This additional level of scrutiny results in better-informed decisions and outcomes

The antimicrobial pharmacy team at CUH works closely with the microbiologists and in-house digital pharmacy team to look at ways of integrating AMS within its electronic patient record system.

Some of the main interventions implemented by CUH to date include customised mandatory indications; the electronic recording of the reason for an antibiotic prescription; default stop dates for every antibiotic to reduce the likelihood of extended dosing; and 48-hour electronic review reminders for clinicians prescribing antibiotics.

“Epic also enables clinicians to remotely collaborate with colleagues in areas such as pharmacy, microbiology, pathology and radiology, and discuss results in real time,” says Santos.

“This additional level of scrutiny results in better-informed decisions and better outcomes.”

The system also enables virtual ward rounds to be conducted, where an antimicrobial pharmacist and microbiology consultant review patients on broad-spectrum or restricted antimicrobials, allowing for timely interventions.

However, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust does not yet have access to electronic prescribing, which has presented a challenge.

“The biggest challenge was having paper drugs charts,” says Ogundana.

“As we do not currently have ePMA [electronic prescribing and medicines administration], one of the challenges was to physically attend the ward to amend the prescription post-review, which can prove time consuming. This will be overcome post-implementation of ePMA.”

Nevertheless, switching over to drug charts that have a dedicated section for antimicrobial prescribing was a big help.

“It had all the pointers for prescribers in terms of reviewing within 72 hours and duration as well,” she says.

At Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, chief pharmacist Alison Tennant hopes that — following its rollout over the next 12 months — e-prescribing will allow for more data gathering on antibiotic use, as well as access to more timely data.

2. Change culture

Public awareness of AMR is spreading through initiatives such as Public Health England’s Keep Antibiotics Working campaign and the World Health Organization’s World Antibiotic Awareness Week.

We’re trying to change culture to thinking about antibiotics as a precious resource, as opposed to a safety blanket

Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust sends out a quarterly newsletter to make healthcare staff aware of the trust’s antibiotic consumption. For Ogundana, this, along with providing education and training, has been critical to the success of its strategy.

Tennant’s team, in partnership with the microbiology team and junior doctors, conducted an awareness initiative during World Antibiotic Awareness Week on 18–24 November 2019, which included inserting one-minute videos into meetings around the hospital to bring AMR to the forefront of everyone’s minds.

“We’re trying to change culture to thinking about antibiotics as a precious resource, as opposed to a safety blanket,” says Tennant, whose trust saw a 22.6% reduction in overall antibiotic use between 2017/2018 and 2018/2019.

Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust has the highest outpatient attendance of all the paediatric centres in the country, so the AMS message needs to reach concerned families as well as patients.

“A lot of our chronic patients will hold antibiotics to be used in case of an emergency — [it’s important to get them] to think about the wise use of antibiotics and that [antibiotics] are not necessarily the first place they need to go,” explains Tennant.

Birmingham’s decision to involve patient groups, including teenagers, to communicate its AMS strategy to other patients has meant that the message about why antibiotics need to be preserved comes from those directly affected by AMR.

“The patient engagement element here has made a huge difference … and the fact that it’s children makes a huge impact. A [patient with cystic fibrosis] telling you the bugs they’ve got are becoming resistant to the antibiotics [they’re taking] has a much greater impact when it is a child.”

Specialising in children means that many of the antibiotics provided in Birmingham are given parenterally.

“We’re doing a big piece of work at the moment about what’s given down [intravenous] lines and what can be given together, and that’s another opportunity for us to intervene with the ‘do you actually need to give these antibiotics and, if you do, how long do you give them for’ message,” says Tennant.

Continuing antibiotics for an extra few days does have an impact

However, Tennant’s team has had some challenges in getting the AMS message heard in its busy emergency department.

“The emergency department has been a particular challenge in terms of getting that message across that antibiotics are not always needed,” she says. “We have a very busy emergency department — families will [bypass] other hospitals to bring their children here.”

Despite the “extra emotional element” of dealing with sick children and concerned parents in the emergency, Tennant says, it is still critical to ensure that the right decision is made when it comes to antibiotics and to communicate that antibiotics are not always the answer.

“Continuing [antibiotics] for an extra few days does have an impact,” she adds.

3. Work with others

At Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, an essential factor of the trust’s AMS success lies in the support Ogundana has gathered across the hospital. She works closely with the microbiology team and accompanies the microbiologist consultant on ward rounds to review patients on antimicrobial treatment.

“We have support from all the clinicians and senior consultants, head of department, pharmacy colleagues — there is an awareness about antimicrobial prescribing,” she says.

However, it did take time to get the senior clinicians onboard.

“They had not had a pharmacist challenge [their] prescribing choices before — they had not had people say, we don’t use this treatment, this is what we use now,” recalls Ogundana.

“But as we made them more aware of our guidelines, they started to follow the recommendations.”

Unusually, in Birmingham, the AMR programme at the trust has a strong consultant leadership, making it “easier to get a consistent message out”, Tennant explains.

As we work together, and have other measures in place, that will reduce our consumption even further

Overall, she says that the 22% reduction achieved is the outcome of a range of factors, including the 2016 merger between Birmingham Women’s Hospital and Birmingham Children’s Hospital, which saw a change in the mix of antibiotics being consumed, and shortages of antibiotics in recent years.

The hospital is about to invest in data analysis to enable better use of the data being collected. This will be aided by the rollout of e-prescribing, which Tennant hopes will enable review periods to be flagged to track use of antibiotics across specific patient groups.

Moving forward, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust is planning to work closely with other hospitals in the area with the eventual aim of centralising prescribing practices. “As we work together, and have other measures in place, that will reduce our consumption even further,” says Ogundana.

At CUH, there are plans to invest in additional staffing, including a rotational antimicrobial pharmacist, and to focus on the effective screening of high-risk patients to enable identification of individuals who are harbouring resistant infections before they spread to others.

The team also intends to use big data to develop various algorithms to help them assess the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing in real time for common indications.

“This promises to revolutionise the way we view antibiotic prescribing audits in the future,” says Santos.

Box: Commissioning for Quality and Innovation

Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) was introduced in 2009 to make a proportion of healthcare providers’ income conditional on demonstrating quality improvements and transformational change.

The sum attached to CQUIN varies per year, based on a percentage of the contract value and depending on whether certain quality improvement and goals have been achieved.

The national CQUIN indicator, ‘Reducing the impact of serious infections (antimicrobial resistance and sepsis)’, aims to encourage the timely identification and treatment for sepsis and reduce clinically inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and consumption.

There are four parts to this CQUIN indicator: timely identification of sepsis; timely treatment for sepsis; antibiotic review; and reduction in antibiotic consumption per 1,000 admissions and the proportion of antibiotic usage within the Access, Watch and Reserve antibiotic categories, created by the World Health Organization to assist antimicrobial stewardship.

To receive payment in 2018/2019, trusts were required to achieve a 1% reduction in total antibiotic consumption in 2018/2019 if they had achieved the target 2% reduction in 2017/2018, or a 2% reduction if they had failed to reach the 2017/2018 target.

References

[1] Public Health England. 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/843129/English_Surveillance_Programme_for_Antimicrobial_Utilisation_and_Resistance_2019.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[2] Public Health England. 2019. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/amr-local-indicators/data#page/3/gid/1938132909/pat/15/par/E92000001/ati/118/are/REM/iid/92201/age/1/sex/4 (accessed November 2019)

[3] NHS England. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/cquin-indicator-specification-information-january-2019.pdf (accessed November 2019)