Shutterstock.com/The Pharmaceutical Journal

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the role of essential antimicrobial stewardship tools and frameworks to improve antibiotic prescribing;

- Structure an antimicrobial review effectively, covering all relevant details;

- Personalise the antimicrobial review to ensure patient-centred care and effective antimicrobial stewardship practices;

- Develop skills for effective antimicrobial review and stewardship practices to mitigate antimicrobial resistance threat.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) significantly impacts global public health, having been linked to approximately 4.95 million deaths in 2019[1]. This resistance places a strain on healthcare systems and carries considerable economic implications. A main factor driving AMR is the consumption of antibiotics, with higher usage promoting resistance both at population and individual patient levels[1]. Although antibiotic use varies widely between and within healthcare systems, antimicrobial reviews provide crucial opportunities to optimise antibiotic prescribing and reduce the misuse of antibiotics. Strategies to reduce overuse in hospitals hinge on prescribers making informed decisions to discontinue unnecessary antibiotic medicines; however, there is limited evidence on how to best support these critical decisions. The aim of antibiotic reviews is to decrease the misuse of antibiotics by encouraging healthcare professionals to make appropriate decisions and promote effective use of medications to address the challenges of AMR[2].

Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) aims to minimise resistance by ensuring that antibiotics are prescribed only when clinically indicated and that narrow-spectrum agents are used whenever appropriate[3]. Within the UK, tools and policies have been developed to provide best-practice guidance on AMS. The Antimicrobial Prescribing and Stewardship competency framework, originally published in 2013 and revised in August 2023, acts as an integral guide within England to enhance the calibre of antimicrobial treatment and stewardship, and thus mitigate the risks associated with inadequate antimicrobial usage. It is in accordance with England’s code of practice for AMR, the UK’s 20-year vision for AMR, and the 5-year action plan for AMR[4]. The framework is designed to support prescribers in various care settings, advancing their proficiency in antimicrobial prescription and stewardship practices. Emphasising patient-centred care and judicious decision making, the framework’s goal is to curtail the development of AMR and improve the management of infections, ensuring improved patient safety and quality of care[4]. Despite the presence of the framework and efforts to improve awareness for AMR and training in stewardship best practice, evidence suggests that progress can be uneven. A study at an English NHS Foundation Trust examined antibiotic prescribing trends for respiratory tract infections during 2019/2020 and observed an increase in antibiotic use during the COVID-19 pandemic, reinforcing the value of antibiotic review and AMS practices in addressing AMR[5].

The ‘Start Smart Then Focus’ toolkit, first published in 2011 and most recently updated in September 2023, provides clinicians and healthcare leaders within England’s inpatient settings with a robust framework for AMS. It aims to mitigate AMR and uphold patient care standards through evidence-led protocols. The resource guides initial, judicious antimicrobial application, followed by a critical review and refinement of treatment, secured in clinical data and diagnostic insights. Additionally, it sets out best practice components for antimicrobial prescribing and comprehensive stewardship programmes, advocating the importance of regular audits, education and delineated responsibilities across the healthcare team. Compliance with the toolkit’s directives is crucial to meet the regulatory requirements of England’s healthcare system, ultimately contributing to the national efforts to reduce the risk of AMR while safeguarding the quality of care for patients with infection[6].

To support these aims, the National Institute for Health and Care Research funded a project to develop an intervention designed to facilitate multifaceted behaviour change to reduce antibiotic use in acute general medical inpatients safely, culminating in the antimicrobial review kit (ARK). The ARK creates a structured process that promotes optimised prescribing and provides timely opportunities for prescription review, where appropriate optimisation decisions could be made[7]. Effective antibiotic review is crucial to enhance audits. It is important that initial prescriptions comply with local antimicrobial guidelines and are subject to review within 72 hours of the initial prescription to maintain robust AMS and optimise antibiotic utilisation[7]. Although the ARK intervention was initially developed for acute hospitals, the underlying principles apply equally to pharmacists working across all sectors[8]. This article will provide practical tips and advice on how clinical antibiotic reviews can be effectively conducted.

Best practice for effective antibiotic review and antimicrobial stewardship

The following information summarises the main criteria of best practice with regard to safe and effective antimicrobial prescribing, and advice on how to effectively structure an antibiotic review. AMS best practice principles should be followed at each stage of the prescribing process, and the review stage can be used as a safety net to evaluate their implementation[6].

Initial assessment

This is conducted at the time of the initial antibiotic prescription. Prescribers should begin with the ‘Start smart’ principle by verifying the presence of infection through patient history, clinical signs, laboratory results and imaging. Confirm the primary diagnosis, any healthcare-associated risk factors and whether the patient is immunocompromised or in need of emergency antibiotics for sepsis. It is essential to differentiate between empirical antibiotics and pathogen-directed antibiotic medicine[6,9]. Empirical therapy is based on the prescriber’s initial impression of the most likely cause of the infection and initial diagnosis based on the local antimicrobial guidelines. It should be informed by an assessment based on the history, symptoms, main diagnosis and severity of the infection.

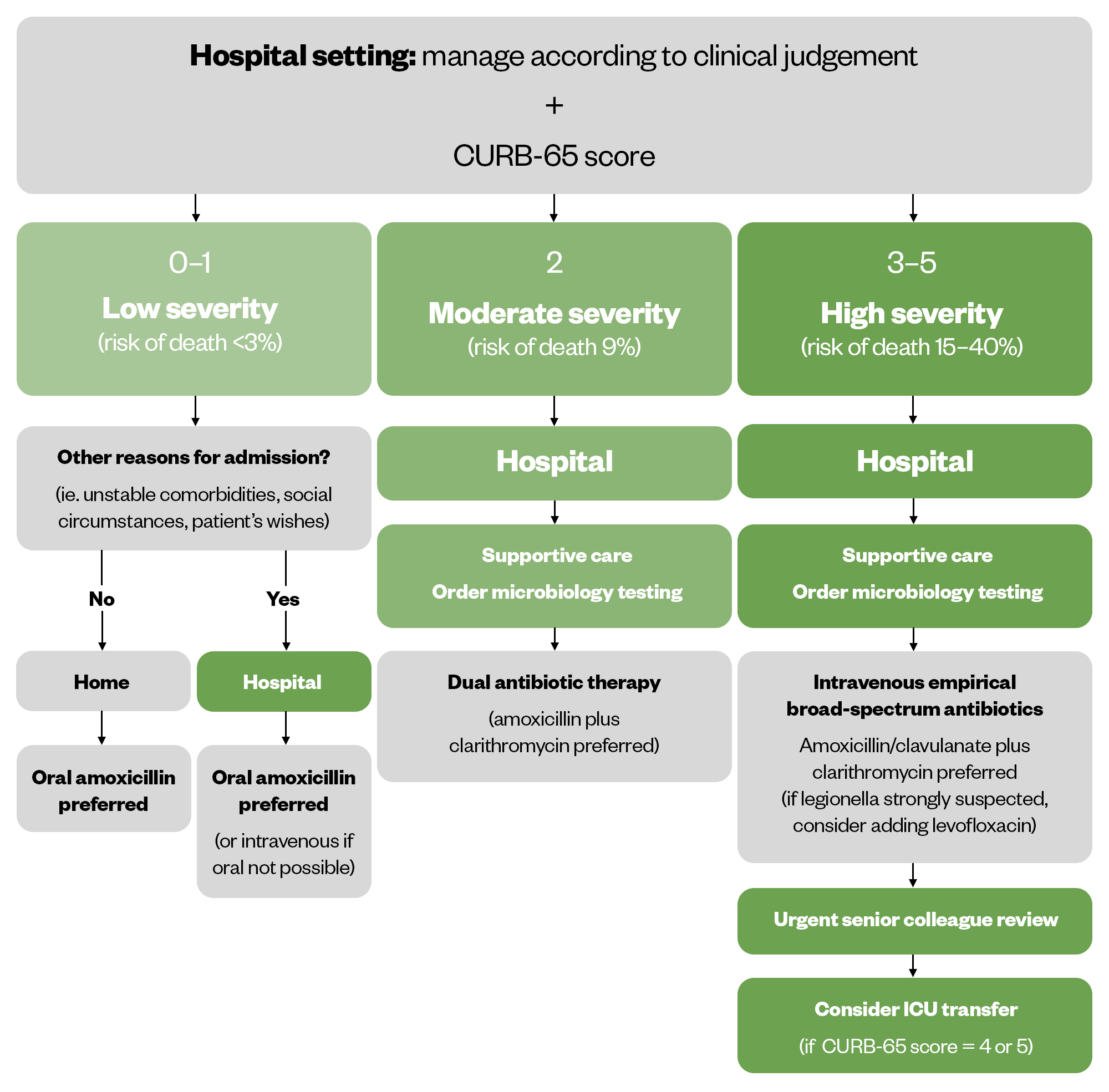

In community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), for example, several evidence-based tools have been developed to optimise empirical antibiotic therapy, including the CURB-65 tool for risk assessment[10].

The CURB-65 tool uses a scoring system that includes five prognostic indicators, each contributing one point: Confusion; Urea levels above 7mmol/L; Respiratory rate over 30 breaths per minute; Blood pressure under 90mmHg systolic or 60mmHg diastolic; and Age 65 years or older[9]. A score of 0 or 1 indicates low severity, 2 indicates moderate severity, and a score between 3 and 5 reflects high severity[11]. The CURB-65 risk assessment framework for CAP is shown below[11].

Allergy status

Accurately determining a patient’s penicillin allergy is vital, as more than 90% of those labelled as allergic are not[12]. This mislabelling often leads to the use of less effective, second-line antimicrobials, increasing costs and adverse outcomes. Healthcare providers should audit the documentation of penicillin allergy status and its source[6].

Diagnostic tests, including microscopy, culture and sensitivity

Utilising microscopy, culture and sensitivity tests aids in the appropriate selection of antimicrobials, especially in cases of treatment failure. Actions taken following these diagnostic test results should be audited[6].

Choice of antimicrobial agent(s): Use the “Then Focus” approach within 48—72 hours of initial prescription to review the patient’s response to the initial empirical therapy and laboratory data[6]. Choose antimicrobials based on both empirical evidence and culture results, tailoring the choice to the patient’s specific needs. Ensure adherence to the five rights (5Rs) of antibiotic safety, including the right patient, drug, dose, time and duration, in accordance with local antibiotic guidelines[13]. Selecting the appropriate antimicrobial therapy is crucial to avoid healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs), AMR, and unnecessary drug exposure. This choice should adhere to local guidelines and include auditing the dose and route of administration[6].

Identify the likely pathogens through culture data and match them against the pharmacology of available antimicrobials, taking into account the site of infection and penetration efficacy of the drugs[6].

Person-centred care

Being person-centred means individualising care for each patient, ensuring the safe prescription of antibiotics, and taking into account necessary dosage adjustments, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics[14]. The role of pharmacy in delivering person-centred care is pivotal. Pharmacists need to be recognised as part of the multidisciplinary team that can support people with infections and other comorbidities, such as kidney and liver diseases or immunocompromised patients in any setting[9,15].

Antibiotic side effects (e.g. tendon rupture with fluoroquinolones, kidney issues with aminoglycosides) should be explained to patients, with consideration given to their level of health literacy and the most appropriate means of communication for the individual.

Dose adjustments or changes in medication should be considered when necessary, such as renal dose adjustments for vancomycin and meropenem. Potential drug interactions should also be discussed with the patient, including drug–drug, drug–food, and drug–disease reactions, such as erythromycin and statins, which can interact, increasing statin side effects, and dairy products, which can inhibit the absorption of tetracycline antibiotics.

Total duration of antimicrobial therapy

Treatment with antimicrobials should not exceed five to seven days (including both intravenous and oral) unless specific guidelines or specialists recommend otherwise[6]. Shorter antimicrobial courses have been shown to be equally effective for uncomplicated infections, and can reduce adverse effects and resistance pressure[16]. Auditing compliance with local guidelines for the total duration of therapy for each type of infection is recommended[6,16].

Documentation

Record the diagnosis, antibiotics used and review date. Documentation should be thorough to facilitate clear communication and continuity of care. A review date or expected duration on antimicrobial prescriptions should be documented to prevent indefinite treatment and reduce AMR risk[6,17].

Interprofessional collaboration

Communicate effectively with the healthcare team, including prescribers, about antibiotic therapy choices and changes based on the patient’s microbiology results and clinical conditions[4,6].

Patient education

Engage in shared decision making with the patient, ensuring they understand the rationale for the use of antimicrobials. Educate patients and healthcare professionals on the appropriate use of antibiotics at every opportunity[17]. Provide counselling on the use of antibiotics as prescribed and the implications of AMR, and repeat these messages at the review stage. Use evidence-based resources to support education and encourage prudent antibiotic use[18,19].

Possible outcomes of the antimicrobial review

Evidence indicates that a ‘review and revise’ approach reduces mortality risks[6]. Once the antimicrobial review has been completed, there will be five potential outcomes: Cease, Amend, Refer, Extend or Switch for effective treatment management[6,20]. This is referred to by the mnemonic ‘CARES’, which is explained further below[6,21].

Cease

- Stop antimicrobial treatment if no infection is present to prevent harm and resistance;

- Evidence supports ending treatment early if no infection signs are found, improving survival rates[6];

- Strategies should focus on reducing unnecessary antimicrobial use to prevent resistance escalation.

Amend

- Amend antimicrobial prescriptions, ideally choosing a narrower-spectrum agent, or a broader one if necessary, to ensure effective and proportionate treatment[6];

- Change prescriptions to narrower agents when possible to enhance both effectiveness and safety[6];

- A recent study emphasised the significance of the ‘De-escalation’ AMS strategy, or changing to narrower antibiotics, during emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic[9].

Refer

- Direct suitable patients to non-ward-based services or virtual wards for continued care. These services have been shown to be safe and effective and can lead to high patient satisfaction[6];

- Referrals to non-ward based services can enable an early switch from IV to oral antimicrobials, aligning with UK best practice guidelines[22].

Extend

- Continue antimicrobials only when clinically necessary, with a documented review or stop date;

- Shorter courses are often as effective as longer courses and reduce the risk of developing resistance[15]

- Unnecessary extended courses of antibiotics can lead to increased resistance and adverse effects[23].

Switch

- IV-to-oral Switch (IVOS) criteria are pivotal in enhancing patient recovery and reducing risks[6,22];

- Studies confirm early IVOS is as effective as prolonged IV treatment[6];

- Benefits include reductions in infection risk, healthcare costs and environmental impact.

Case study

D.L. is a woman, aged 44 years, who attended A&E in June with a sudden onset of cough, lethargy and fever with chills over the past four days. She lives with her partner and maintains a healthy lifestyle, running 25 miles per week as part of a running club. She has not travelled recently and works from home. Her vital signs show a respiratory rate of 32 breaths per minute, blood pressure at 124/71mmHg, heart rate at 98 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation of 93% while breathing room air. Her white blood cell count is elevated at 19.0×109/L, and she has a fever of 102.1°F (38.9°C). Her blood urea nitrogen level is 17mg/dL. She is conscious and alert. A chest X-ray shows a consolidation in the left lower lobe of her lung. She has been admitted to the hospital for pneumonia treatment.

What is D.L.’s CURB-65 score?

A. 1

B. 2

C. 3

D. 4

Answer: A

The CURB-65 score can be used to assess a patient’s risk of mortality related to pneumonia and to make hospital admission decisions. One point is assigned for each of the five criteria the patient meets; they are then summed for the final CURB-65 score.

In this case, the patient is not confused (0 pt), and BUN is no greater than 19mg/dL (0 pt); the patient’s respiratory rate is greater than 30 breaths per minute (1 pt), she has a blood pressure greater than 90/60 mm Hg (0 pt), and she is younger than 65 years (0 pt). Therefore, her CURB-65 score is 1 (Answer A is correct; Answers A, C, and D are incorrect).

The patient received amoxicillin orally. On day 5 of hospitalisation, D.L has improved. Her current vital signs are a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 112/70mmHg, and heart rate of 70 beats per minute. Her oxygen saturation is 98% while breathing room air. Her last fever was 73 hours ago, and her WBC is 12 x 103 cells/mm3. D.L. is being discharged today.

Which of the following options is most appropriate as the next step for her?

A. Discontinue antibiotic therapy

B. Continue antibiotic therapy for two more days with azithromycin orally at discharge

C. Continue antibiotic therapy for two more days with ceftriaxone orally at discharge

D. Continue antibiotic therapy for two more days with levofloxacin orally at discharge

Answer: A

This patient has been afebrile for more than 48–72 hours, is saturating well on room air, is normotensive, and has a normal heart rate and respiratory rate. She has no signs of clinical instability. Given this, it is safe to discontinue antibiotic therapy now (Answer A). Answers B–D are incorrect because she does not require additional therapy, given her clinical stability. If she did require additional therapy, levofloxacin would be suboptimal, given the risk of tendon rupture and other adverse effects, and azithromycin would be suboptimal as well, given the high risk of S. pneumoniae resistance and lack of concern for atypical pathogens in this case.

- 1Antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20bacterial (accessed February 2024)

- 2Llewelyn MJ, Budgell EP, Laskawiec-Szkonter M, et al. Antibiotic review kit for hospitals (ARK-Hospital): a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2023;23:207–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00508-4

- 3Antimicrobial stewardship. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/infections/antimicrobial-stewardship (accessed February 2024)

- 4Antimicrobial prescribing and stewardship competency framework. UK Government. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-prescribing-and-stewardship-competencies/antimicrobial-prescribing-and-stewardship-competency-framework#using-the-aps-competency-framework (accessed February 2024)

- 5Abdelsalam Elshenawy R, Umaru N, Aslanpour Z. WHO AWaRe classification for antibiotic stewardship: tackling antimicrobial resistance – a descriptive study from an English NHS Foundation Trust prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1298858

- 6Start smart then focus: antimicrobial stewardship toolkit for inpatient care settings. UK Health Security Agency. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-start-smart-then-focus/start-smart-then-focus-antimicrobial-stewardship-toolkit-for-inpatient-care-settings#section-2-sstf-principles—-then-focus (accessed February 2024)

- 7Implementation. Antibiotic Review Kit. 2020. https://antibioticreviewkit.org.uk/implementation/ (accessed February 2024)

- 8Cross ELA, Sivyer K, Islam J, et al. Adaptation and implementation of the ARK (Antibiotic Review Kit) intervention to safely and substantially reduce antibiotic use in hospitals: a feasibility study. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2019;103:268–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2019.07.017

- 9Abdelsalam Elshenawy R, Umaru N, Aslanpour Z. Impact of COVID-19 on ‘Start Smart, Then Focus’ Antimicrobial Stewardship at One NHS Foundation Trust in England Prior to and during the Pandemic. COVID. 2024;4:102–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4010010

- 10Pneumonia (community-acquired): antimicrobial prescribing . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng138 (accessed February 2024)

- 11Community-acquired pneumonia (non COVID-19). BMJ Best Practice. 2020. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000108/management-recommendations (accessed February 2024)

- 12Millions mistakenly think they are allergic to penicillin. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2023. https://www.rpharms.com/about-us/news/details/millions-mistakenly-think-they-are-allergic-to-penicillin- (accessed February 2024)

- 13Elshenawy RA, Umaru N, Aslanpour Z. An evaluation of the five rights antibiotic safety before and during COVID-19 at an NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2024;36:188–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2023.12.019

- 14Role of pharmacy in delivering person-centred care. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2015. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/reports/role-of-pharmacy-in-delivering-person-centred-care (accessed February 2024)

- 15Johnson D. How to work effectively as part of a multidisciplinary team. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-to-work-effectively-as-part-of-a-multidisciplinary-team (accessed February 2024)

- 16Wilson HL, Daveson K, Del Mar CB. Optimal antimicrobial duration for common bacterial infections. Aust Prescr. 2019;42:5. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2019.001

- 17Powell N, Stephens J, Rule R, et al. Potential to reduce antibiotic use in secondary care: Single-centre process audit of prescription duration using NICE guidance for common infections. Clin Med. 2021;21:e39–44. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0141

- 18Shaikh A. Writing patient notes: a guide for pharmacists. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/writing-patient-notes-a-guide-for-pharmacists (accessed February 2024)

- 19Rajiah K, Coleman H, Elnaem M, et al. How pharmacy teams can provide health education. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-pharmacy-teams-can-provide-health-education (accessed February 2024)

- 20Balaj M, Henson CA, Aronsson A, et al. Effects of education on adult mortality: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(23)00306-7

- 21Elshenawy RA, Umaru N, Alharbi AB, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship implementation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the acute care settings: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2023;23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15072-5

- 22Ashiru-Oredope D, Attwood H, Cullum R, et al. Switching patients from IV to oral antimicrobials. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/switching-patients-from-iv-to-oral-antimicrobials (accessed February 2024)

- 23Antimicrobial Resistance and Stewardship. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2023. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/ams-amr (accessed February 2024)