Julie Lee / The Pharmaceutical Journal

“I thought I was too young to retire,” says David Evans, chief pharmacist and managing director at the East Midlands-based small multiple Evans Pharmacy, when he is asked why he held on to 10 pharmacies during the sale of a much larger 65-pharmacy chain three years ago.

Since setting up the new business in February 2016, Evans has acquired two more pharmacies. One had been in the pipeline for a long time and the other presented an opportunity to work closely with a GP surgery.

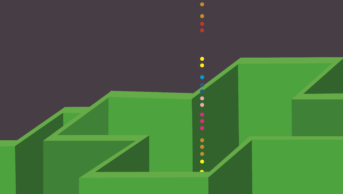

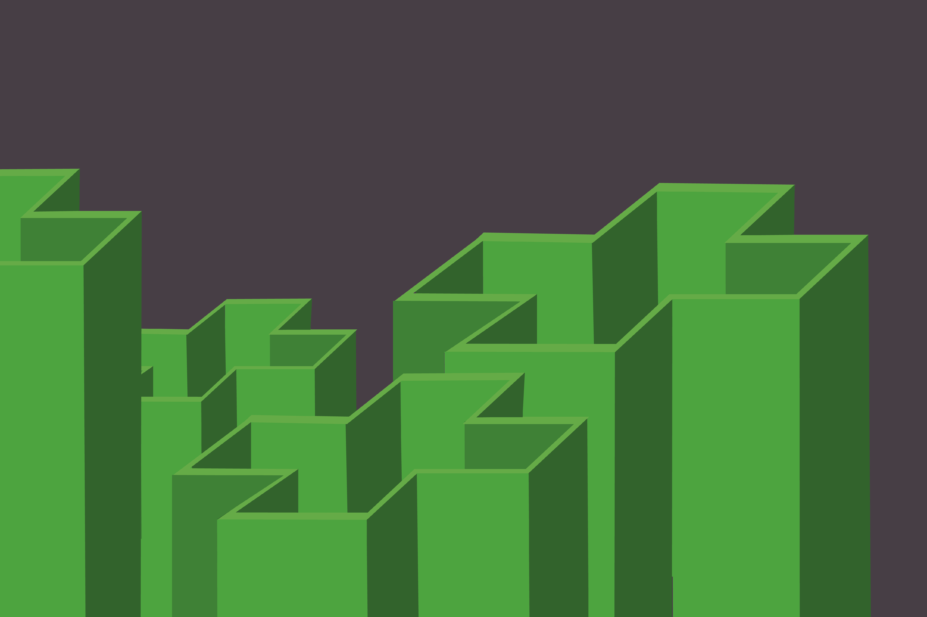

And he is on trend. In contrast to the big multiples, their smaller counterparts (those with 6–99 pharmacies) have increased their hold from a 12.61% market share to 13.30% (a net increase of 92 pharmacies [see Infographic]). Despite this, however, you won’t find Evans celebrating.

The small independent multiple sector might be thriving in terms of numbers, but I don’t think anyone’s thriving financially

“Like everyone, we’re struggling,” he says. “The small independent multiple sector might be thriving in terms of numbers, but I don’t think anyone’s thriving financially.”

Evans was able to finance the acquisitions using family investment. Banks are still prepared to lend, he says, but they are starting to ask more questions.

To buy or not to buy?

Peter Cattee, chair of the Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies and chief executive of PCT Healthcare, a chain of 118 pharmacies, has a long history of buying and selling branches. His company grew significantly in 2016 when he acquired Evans’s family business. “We took over the business two months after the government announcement [on funding cuts in England in December 2015] but [the purchase] had started 18 months before that when pharmacy was in a different place,” Cattee explains.

More recent acquisitions reflect a positive outlook, he suggests. “Contractors may see a brighter future, but it says more about their view of the world than of pharmacy.”

Evans is scratching his head. “If the big multiple can’t make it work, how’s the small multiple going to make it work?” he asks.

David Evans, chief pharmacist and managing director at Evans Pharmacy, said he doesn’t think “anyone’s thriving financially”

Saghir Ahmed, a director at Imaan Healthcare, is more positive. The company, a growing chain of 48 independent pharmacies, bought 21 pharmacies in 2018, spying an opportunity to strengthen its presence in areas where it already had good working relationships with local GPs and commissioners. “We felt that … we’d be able to exploit that,” says Ahmed. “We’ve done our own calculations and our own analysis and thought that, for some of the pharmacies [up] for sale, we could deliver them better.”

We don’t need to have layers and layers of management and bureaucracy; it allows us to be a lot more agile

Ahmed says that the key to success is giving pharmacies a degree of autonomy. This allows decisions to be made locally, which is particularly important for the branches that are located far from the company’s base in the north-west of England. “We don’t need to have layers and layers of management and bureaucracy. It allows us to be a lot more agile.”

Having a head office close to branches is something that can give small multiples an edge over larger companies. “If something goes wrong, it’s easier for me to mobilise and offer support to those branches,” says Ahmed. Cattee agrees: “The ability to manage pharmacies is inversely related to your distance from them. There is so much local variation that contractors need to be a local expert.” Having geographically concentrated businesses with local networks is one way that small multiples have reduced their financial risk, he explains.

The relative success of small multiples, “if success is the right word”, says Evans, comes down to a better critical mass and a flexibility around innovation. “Independents don’t necessarily have the pooled resource of a small multiple, and large multiples are too inflexible,” he says.

But Cattee is not convinced that smaller businesses have an advantage. “There is not enough cake to go around,” he says. “There is little chance that total remuneration will increase, so we’re all increasingly fighting for a larger share of a diminishing whole. Does agility help smaller businesses?” he asks. “Not in the current structure of pharmacy.”

Survival strategies

In business, it is normal to have one-, three- and five-year strategies in place. “By and large we have that,” says Ahmed. “But you can’t be fully confident that those strategies are going to stay the same because you don’t really know what’s around the corner.”

Ahmed cites a “ridiculous payment mechanism” for community pharmacy, whereby contractors do not know what they will be paid for dispensing prescriptions from one month to the next. “You can go from getting, say, £8.70 per item, and the following month it falls to £8.10 and you can’t figure out why.”

And when businesses are unable to forecast, it becomes increasingly difficult to know how much money will be available for investment.

At the moment, return on capital is woefully unacceptable, says Cattee. And to expect that people will simply invest their way out of this is a dangerous strategy. For Cattee, there are “too many unknowables” relating to most aspects of community pharmacy, which means that initiatives such as central dispensing and hub-and-spoke models might not be sensible. “These will only shift costs, reducing assembly cost but increasing logistics,” he says. “There seems to be a general agreement that such changes are primarily to free capacity, but without a more clinically based future visible, where is the incentive?”

It can only be to the detriment of both patients’ needs and the development of our profession if we are forced to concentrate solely on the price of the service

Cattee suggests that, under such extreme pressure, contractors may be forced to compromise on quality when trying to strike a balance between that and cost. “Businesses have no choice — they’ve taken on long leases, taken on debt and they need to meet these commitments,” he says. “But it can only be to the detriment of both patients’ needs and the development of our profession if we are forced to concentrate solely on the price of the service.

“We have been forced into doing this for several years now, and it is holding us back.”

The risk is that less profitable pharmacies that provide important social functions will close. “Economics is taking over, over the greater needs of the health service,” says Cattee. “The way to survive this is not to improve services. A policy of attrition weakens the profession.”

Source: Courtesy of Peter Cattee

Peter Cattee, chair of the Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies and chief executive of PCT Healthcare, says that, at the moment, return on capital is woefully unacceptable

Cost containment is an important business strategy across all sectors, suggests Cattee, but there is little inefficiency that can be driven out.

At Imaan Healthcare, staff costs are being considered carefully and branch opening hours trimmed. “We want to provide an accessible service, but there’s only so much you can do,” says Ahmed, who has stopped Saturday provision for some branches. “It would be irresponsible of me not to make those calls because by acting on those decisions you’re adding stability.”

We’re … sitting it out and trying to gain market share from reductions in other people’s service and from closures

So far, Evans has resisted any reduction in his branch opening hours but says it is something he will need to consider for one or two of his pharmacies. Several competitors no longer open at the weekend, which has shifted some Saturday trade his way. “We’re … sitting it out and trying to gain market share from reductions in other people’s service and from closures,” he says.

Invest to grow

Despite the challenges, some investments are being made. Evans has invested in a central robot for dispensing into monitored dosage systems. “That allows us to moderate the work flow at each branch.” He is also investing in staff and making better use of the skill mix available to him. He employs around 20 pharmacists; 40% of whom either have, or are working towards, postgraduate qualifications.

“We’re looking at extra training to upskill our pharmacists to provide extra services; we’re using pharmacist prescribers and better trained staff to alter the work balance within each pharmacy.”

We second staff into both surgeries to work at a clinical pharmacist level; it’s really good for multidisciplinary working and working relationships

Evans has two surgery-based pharmacies among his portfolio. “We second staff into both surgeries to work at a clinical pharmacist level. It’s really good for multidisciplinary working and working relationships,” he says.

To support his strategy, Evans has tapped into the Pharmacy Integration Fund — something he says has become easier to access over the past six months. “There seem to be less strings attached [to the fund] now.”

Many small groups are also looking at new revenue streams to supplement their income and profitability. Service provision is an important area of growth for Imaan Healthcare; the company is focusing on conditions that are particular issues in the areas it serves: diabetes, COPD and mental health (see Box). It needs to prove its worth before commissioners will take it seriously as a service provider, which requires investment and strong relationships.

“You can’t expect people to give you money to provide some work if you can’t give them any data and evidence to say that you can deliver it,” he explains. “For every five services that you design, there’s a chance that maybe one or two of them might get funded. But if you don’t shoot, you don’t score.”

Box: Community care

Imaan Healthcare’s prediabetes service has got off to a good start in Oldham and now attracts funding from the clinical commissioning group (CCG). Pharmacists connect with their local communities, visiting libraries, football matches, churches, mosques and other public areas, where they provide HbA1c and cholesterol point-of-care testing. Individuals considered to be at risk of developing diabetes are referred to the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme.

“We developed a really good relationship with one particular person [within public health] at Oldham City Council,” says Ahmed. “She invested a lot of time into this work and it also helped that she knew people at the CCG and was able to open doors for us.”

The company now plans to approach local authorities and CCGs in Derby, Hounslow and Preston, where diabetes is also a significant issue.

Evans has also prepared his pharmacies to offer extra services, but says activity is disappointing. The digital minor illness referral service, which sees patients referred to community pharmacy from NHS 111, is being piloted across several locations in England, including the East Midlands. All of Evans’s pharmacists attended the training ready for a November 2018 start. “We saw two units of activity in November, no activity whatsoever in December. So, at £14 each, we’ve seen the princely sum of £28 in two months.”

The data for the wider area are no less disappointing. “For a population of over a million people, there were around 50 referrals,” says Evans. “That level of service doesn’t pay the bills; it doesn’t pay the staff.”

Finding the right balance

Cattee believes community pharmacy should reduce its “unhealthy dependency” on the NHS. “When I started out as a contractor, 70% of my business was NHS and 30% was made up of mainly medicine sales. Now it’s 94% NHS.”

He suggests that community pharmacy should be looking to expand private services around diet and weight loss, and to consider how, as a whole network, it can deliver health benefits through the application of genomics. “We also need to engage in preventative health — associate ourselves with gyms. There are lots of areas where pharmacy can be more imaginative.”

Imaan Healthcare is developing a private urgent care clinic with medicines supplied either under a patient group direction or via prescriptions written by pharmacist independent prescribers.

“We’re targeting working patients who don’t want to give half their day or a full day over as annual leave just to go to see the doctor,” says Ahmed.

We’re seeing a few thousand pounds of online over-the-counter sales per month but that only generates, say, £400 worth of income; it’s a drop in the ocean

Another possible income stream is through online over-the-counter (OTC) medicine sales, but Evans says the return is minimal. “We’re seeing a few thousand pounds of [online] OTC sales per month but that only generates, say, £400 worth of income; it’s a drop in the ocean.” And any increase in sales from NHS England’s policy of restricting prescribing of OTC medicines has not been forthcoming. “That’s not a revenue stream as far as I’m concerned,” he says.

Evans’ strategy is to sit it out until the latest Category M clawback unwinds and the community pharmacy settlement, whatever that may be for the next financial year, becomes clear. “Then we can make some informed decisions about how we proceed. Whether that be rationalising, divesting or seeing an opportunity to invest.”

And that decision not to take early retirement? Evans smiles wryly. “With everything else that’s happening now, maybe that was the wrong decision.”