Vibhu Solanki, MRPharmS;[1]

Mehdi Djilani,PharmD[2]

; Sebastian Haag, MD, PhD[3]

Read this article to:

- Obtain insight into the unique role of the community pharmacy team

- Develop your knowledge of the various medications available over the counter for the treatment of frequent heartburn and acid reflux

- Find practical, easy-to-use tips and tools to help guide your dialogue with customers

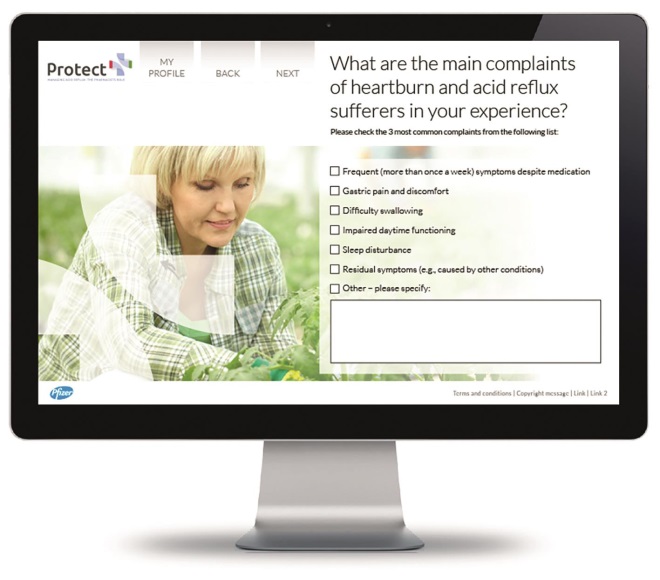

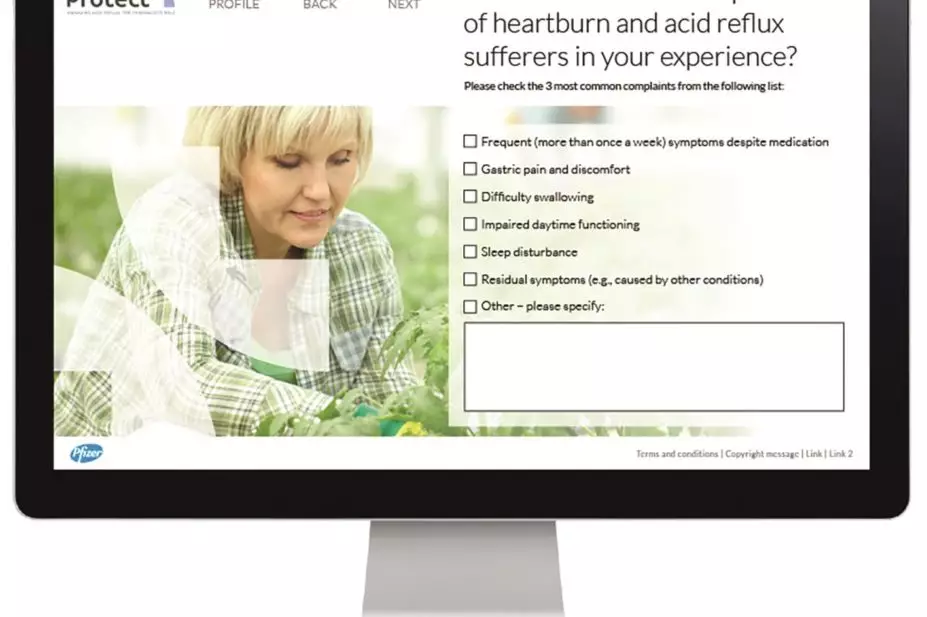

Visit the PROTECT website at

www.protect-cpd.com

for a free CPD-accredited, in-depth and interactive, e-learning programme on advanced pharmacy management of acid reflux’

Despite advances in treatment, heartburn and gastric acid reflux remain an area of unmet medical need. Sufferers of this common chronic condition are affected in multiple areas of their lives, and most are dissatisfied with their current medication (Crawley 2000). An increasing proportion of patients are self-medicating to obtain relief of their frequent, bothersome symptoms. The trend towards self-care highlights the evolving landscape of heartburn and acid reflux management. In the new landscape, a central role is played by the community pharmacy team, who becomes the main point of contact for heartburn and acid reflux sufferers seeking over-the-counter (OTC) remedies (NICE 2004).

Towards a self-care model: the role of community pharmacies

The past decade has seen an increasing reliance of customers on self-medication to help manage a range of medical conditions. The self-care movement is consistent with a shift from prescription-only to OTC medication by pharmaceutical companies across Europe and the US.

Upper gastrointestinal symptoms are a common cause for self-treatment with OTC medication (MeHuys 2009). Between 20% and 40% of people in Western countries report experiencing symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux (Delaney 2004, Haag 2011), and a majority are either referred for self-treatment or choose to self-medicate (MeHuys 2009).

At the same time, as shown by an observational study carried out in the OTC setting in US, heartburn and acid reflux sufferers reliably consult a physician when warranted by their symptoms (Fendrick 2004). Patients’ increasing involvement in self-selecting a treatment course brings with it more responsibility (Brass 2001). It also places a greater emphasis on the role of the community pharmacist, who becomes the first port of call and ongoing consultant to those seeking OTC remedies (NICE 2004).

Improving communication is at the heart of healthcare, from diagnosis through to managing customer expectations, particularly those concerning the chronic nature of acid reflux and the difference between symptom control and freedom from symptoms (Bytzer 2009).

As the main link between the consumer and the product, the community pharmacy team has tremendous capacity to engage, educate and empower reflux sufferers to:

- Describe the main factors underlying treatment choice

- Use OTC medications according to their indications

- Gain knowledge on how to take the medication

- Define appropriate expectations from treatment

OTC management of heartburn and acid reflux – what are the options?

While lifestyle changes, especially concerning dietary intake and timing of meals, may benefit many patients with acid reflux, these alone are unlikely to control symptoms in most patients (DeVault 2005, NICE 2004).

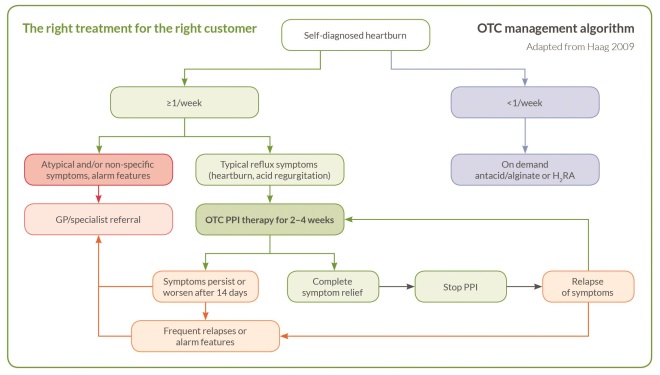

Acid suppression is the backbone of heartburn and reflux treatment, and consumers have a number of OTC choices for managing their symptoms (DeVault 2005, Holtmann 2011). Clinical trial and real-world data have shown that antacids and histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2 RAs) are viable OTC medications in appropriate populations; however, people with frequent (once a week or more) symptoms of heartburn and acid reflux may require more effective therapy.

Drawing from a large body of data, current clinical guidelines universally acknowledge proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) as the drug class providing the best symptom relief among all available medications, and therefore the ‘gold standard’ treatment of reflux disease (NICE 2014).

Visit the PROTECT website at www.protect-cpd.com for a free CPD-accredited, in-depth and interactive, e-learning programme on advanced pharmacy management of acid reflux

Want to see how these considerations apply first-hand to real-world practice? Visit the free PROTECT e-learning programme at www.protect-cpd.com for in-depth, interactive learning structured around a patient story. This continuing professional development (CPD)-accredited programme provides you with a wealth of information, practical tools to share with your team, and additional background reading – all a click away!

How do you discuss PPIs with the frequent heartburn sufferer presenting in your pharmacy?

Here are some of the more challenging questions you may encounter, accompanied by a brief discussion guide and additional resources to refer to.

Q: Shouldn’t I see a physician for my PPI treatment?

A: As your pharmacist, I have the knowledge and tools to guide you through your PPI treatment: how it works, when and for how long you should take it, and what to expect from treatment. I can refer you to a GP or specialist if you do not improve after 14 days of OTC PPI treatment, or if you are experiencing one or more of a set of ‘alarm features’ or atypical symptoms (Haag 2009). Furthermore, your treatment response to a short-term PPI course would ease the further diagnostic approach of a GP or specialist.

Q: What if PPIs mask a more serious condition, such as cancer?

A: There is very little risk of PPIs masking a more serious condition, especially if I recommend it as indicated for heartburn of acid reflux and there are no alarm symptoms present. If symptoms do not get better or return immediately after using the PPI, I can then refer you to the right physician without taking on any significant risk. For your reassurance, studies show that <1 in 1000 of those presenting with reflux are eventually diagnosed with oesophageal cancer (Ruigomez 2008).

Q: I have been symptom-free for 10 weeks after my PPI treatment, but now my stomach pain has returned and I am worried.

A: Gastric pain is a common symptom accompanying acid reflux and it is not correlated with the severity of disease (Haag 2009). Reflux symptoms, including pain, may return after a course of PPIs. This would have been a cause of concern if your symptoms had returned immediately after stopping the PPI. However, your situation is to be expected, and another course of PPI would be appropriate. If you are not able to be without a PPI at all, seeing a physician may be helpful, but not a cause for alarm.

Sponsorship declaration:

This publication was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Mr Vibhu Solanki has served as a consultant for Pfizer.

Dr Mehdi Djilani has served as a consultant for Roche and Ipsen Pharma.

Dr Sebastian Haag has served as a consultant for Pfizer.

This promotional feature is published by The Pharmaceutical Journal on behalf of Pfizer Inc.

Acknowledgements: Medical writing assistance was provided by Ileana Stoica, PhD, of Lucid Group. Financial support to Lucid Group was provided by Pfizer Inc.

References

Brass EP. N Engl J Med 2001;345(11):810–16.

Bytzer P. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7(8):816–22.

Crawley JA, et al. JCOM 2000;7(11):29–34.

De Vault KR, et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:190–200.

Delaney BC. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20 Suppl 8:2–4.

Fendrick MA, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:17–21.

Haag S, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:722–9.

Haag S, et al. Digestion 2009;80:226–34.

Holtmann G, et al. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:493–500.

MeHuys E, et al. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:890–8.

NICE Guidelines 2014 (CG184). Dyspepsia and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Available from http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG184.

NICE Guidelines 2004 (CG17). Managing dyspepsia in primary care. Available from http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG17.

Ruigomez A, et al. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:251–6.

[1] Teacher Practitioner; School of Pharmacy, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom; email: Vibhu.Solanki@nottingham.ac.uk

[2] Pharmacie des Palmiers, Saint Denis d’Oléron, France

[3] Gastro-Praxis Wiesbaden, Germany