Mclean/Science Photo Library

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK’s supplement aisles were packed with shoppers.

With the vitamin and herbal supplement market already growing at around 6% each year across Europe, it experienced a major boost as a result of COVID-19[1]. As public awareness of health and diet spiked, UK consumers turned to supplement-based solutions in their droves, spending an extra £42m on vitamins, minerals and herbal supplements in 2020[2].

According to market research analysts Mintel, a growing interest in boosting immunity, mood and combating stress were all cited as the main reasons for this increase, with the likes of gingko, ginseng and evening primrose all being added to shopping baskets.

However, there could be an unexpected side effect to this fad — the potential for these seemingly harmless supplements to interact with both over-the-counter and prescription medicines.

In 2019, a research paper by EU-funded working group The European Network on Understanding Gastrointestinal Absorption-related Processes (UNGAP) — which aims to advance the field of intestinal drug absorption by focusing on the drug–food interface, among other factors — warned that the growing consumption of herbal supplements required “urgent attention” owing to the potential for dangerous interactions with common medicines[3].

In its review of current evidence, the authors concluded that the ways in which these supplements could impact drug performance necessitated additional “science-based supporting evidence not only on [their] positive effects and safety, but also on [these] potential food–drug interactions”.

Herbal supplements are “generally considered safe” and sold freely in UK pharmacies, says one of the paper’s authors Abdul Basit, a professor of pharmaceutics at University College London.

The concomitant intake of supplements, foods and drugs can influence drug profiles, which may result in adverse drug reactions and altered efficacy

Abdul Basit, professor of pharmaceutics at University College London

“However, [they] can interact with commonly prescribed prescription drugs in a pharmacokinetic manner by modulating the activity of drug-metabolising enzymes and drug-transporter processes, which occur in the gastrointestinal tract,” he explains.

“As a result, the concomitant intake of supplements, foods and drugs can influence drug profiles, which may result in adverse drug reactions and altered efficacy.”

On the other side of the coin, long-term use of some drugs can also induce clinically relevant micronutrient deficiencies (see Box).

The interactions between natural products and drugs are largely based on the same pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles as drug–drug interactions, explains Gill Jenkins, a GP and adviser at the Health and Food Supplements Information Service, a UK-based communication service providing information on vitamins, minerals and other food supplements to the media and healthcare industries.

Pharmacokinetics relate to how the body processes a drug — such as absorption, distribution, metabolisation and disposal — while pharmacodynamics refers to how pharmaceuticals move through the body, influenced by aspects such as an individual’s gastrointestinal tract.

Although the detection of drug–drug interactions is a highly regulated and standardised element of pharmaceutical development, the same rigour is not applied to the production of herbal supplements. As a result — as the UNGAP paper flags — the growing use of food supplements creates the risk that certain food–drug interactions will go ‘undetected’. And, with the COVID-19 pandemic catalysing the consumption of such supplements, this risk could now be significantly increased.

Box: The other side of interaction — how medicines could be impacting nutrient status

The long-term use of some drugs can induce clinically relevant micronutrient deficiencies, which can accumulate over time. As early as the 1970s, studies uncovered a link between high doses of aspirin and reduced vitamin C levels[4].

However, according to Diane McKay, assistant professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts School of Medicine in Massachusetts, the impact of medicines on nutrient status still needs “a lot more research”. “For some drugs, where there is an obvious effect on micronutrient status, you’ll sometimes find warnings in the drug labelling,” she explains. “But, by and large, before my colleagues and I started delving into the literature a few years ago, the studies [available] weren’t of a high quality at all.”

Studies have shown that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can impact the absorption of micronutrients, such as vitamin B12, by reducing the production of gastric acid[5]. In 2017, research on the impact of PPIs on magnesium levels prompted US authorities to update safety information to recommend that healthcare professionals obtain serum magnesium levels prior to prescribing PPIs where patients are expected to be on the medicine for long periods of time. Warnings were also added to the patient information[6].

Despite this, Debbie Grayson, a pharmacist and drug–nutrient expert, says she has seen several patients on PPIs experience critically low levels of both magnesium and B12. “There generally isn’t any advice given to patients about this when the medication is prescribed,” she adds.

This concern is echoed by Mike Wakeman, a pharmacist and healthcare consultant specialising in the effects of medicines on nutrient status. “The impact of drugs on nutrient status is the lesser recognised and lesser understood area [of drug–food interactions],” he believes. “Very often an issue isn’t picked up until someone ends up with a significant deficiency state, such as hypomagnesemia.”

Common interactions

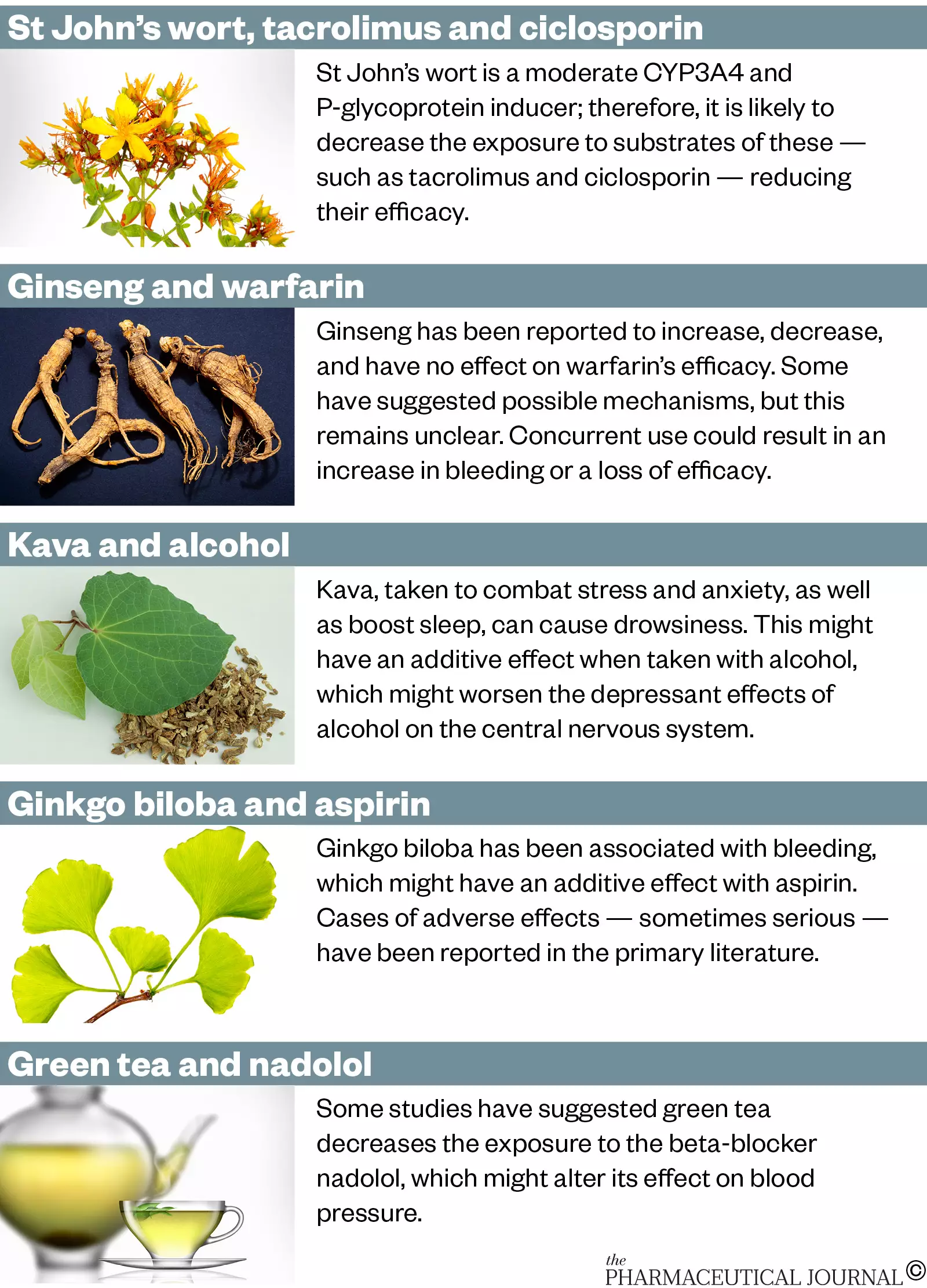

Several interactions between supplements and pharmaceuticals have already been identified (see Figure). “Natural products that have been reported to interact with drugs in humans include co-enzyme Q10, dong quai, ephedra, ginkgo biloba, ginseng, glucosamine sulphate, ipriflavone, melatonin and St John’s wort,” points out Jenkins.

For example, St John’s wort — which is often taken as a supplement to ease the symptoms of depression and anxiety — can interact with levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate, commonly supplied by pharmacists as emergency hormonal contraception[7]. Hyperforin, one of several active constituents in St John’s wort, is a potent inducer of cytochrome P(CYP)450 enzymes, and in particular CYP3A4. This enzyme has been found to be a cause of inactivation for contraceptive steroids since it reduces plasma levels and thereby reduces efficacy[7]. The effects can last for as long as four weeks after a patient takes the supplement.

In 2014, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued a warning to clinicians after 15 reports of unplanned pregnancies from 2000–2014, suspected to be as a result of the interaction between St John’s wort and hormonal contraceptives[8]. Despite warnings already being present on some authorised versions of the supplement, the MHRA said some unlicensed products available online did not contain the same warnings.

Many patients are looking for help with pain and starting to take high supplemental doses of both CBD oil and turmeric, which can be problematic

Debbie Grayson, pharmacist and drug–nutrient expert

Liquorice has also been shown to cause dangerous interactions in patients taking antihypertensive medicines[9]. Studies show that the plant supplement — often taken as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory or to aid digestion — can inhibit the enzyme 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, which is responsible for converting active cortisol into inactive cortisone. This can lead to sodium and water retention and reduced potassium levels, which can increase blood pressure. Patients taking warfarin are also advised to avoid liquorice supplements owing to the risk of toxicity.

Another emerging interaction gaining attention involves cannabidiol (CBD) oil, explains Debbie Grayson, a pharmacist and drug–nutrient expert.

“Many patients are looking for help with pain and starting to take high supplemental doses of both CBD oil and turmeric, which can be problematic,” she explains.

“CBD oil is known to interfere with the CYP enzyme system and can impact the pharmacokinetics of medication with a range of effects, depending on the combination in question.”

Turmeric or curcumin — the principal polyphenol compound in turmeric — can also be problematic from a pharmacodynamic perspective, she adds. Studies have shown that daily consumption of the supplement can have an impact on the prostaglandin pathway, inhibiting the hormones that stimulate the formation of blood clots and the contraction of vessel walls when bleeding. This has an additive effect for patients already taking antiplatelet and anticoagulant medicines, resulting in a significantly increased risk of serious bleeding.

Source: Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions

Regulatory gaps

Basit believes that there are likely to be many more interactions that neither primary care providers nor patients are aware of.

Currently, herbal products and functional foods (that is, foods consumed to beneficially target one or more physiological function in the body rather than purely for nutrition, such as probiotics) “are not required to comply with the same quality control and quality assurance regulations, which exist for pharmaceutical drug products”, he explains. This is despite the fact that herbal products can contain more than 150 components, with a high level of variability between products[10].

A 2018 review of 49 case reports and 2 observational studies investigating herb–drug interactions found 15 cases of interactions leading to elevated liver enzymes, elevated international normalised ratio, gastrointestinal disturbances and kidney damage[11].

Educating the general public to check that the combinations are safe is of utmost importance

Debbie Grayson, pharmacist and drug–nutrient expert

“Potential herbal–drug interactions are understudied by academia and the pharmaceutical industry, under-acknowledged by clinicians and regulatory agencies, unreported by patients and therefore, poorly understood,” Basit sums up.

“The assumption that they are natural and therefore safe is common,” echoes Grayson.

“Educating the general public to check that the combinations are safe is of utmost importance and better knowledge of these interactions by medical practitioners and pharmacists, as well as complementary therapists is key.”

Addressing the issue will therefore require the input of pharmaceutical companies, primary care providers and patients themselves, experts told The Pharmaceutical Journal. On one level, greater research is needed both before and after the developmental stage of pharmaceuticals to better understand the potential for interactions with herbal supplements.

This requires a new standardised testing model, recommends Francesca Gavins, a postgraduate student working alongside Basit at UCL’s School of Pharmacy, specialising in the effects of food on oral drug absorption. Currently, “a standard system for interaction prediction and evaluation of herbal–drug and food–drug interactions does not exist,” she says.

“Systematic evaluation and characterisation of the individual constituents in food and herbal products which are responsible for interactions should be carried out in a similar manner to the investigation of drug–drug interactions for new candidate drug products.”

Nonetheless — as Gino Martini, chief scientist at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, points out — there are already protocols in place to flag worrying interactions.

The Yellow Card scheme operated by the MHRA allows users of either herbal supplements or medicines to report adverse reactions.

“Regulators get involved and there are protocols for actions they should then take, such as putting new warnings out there on the packaging or asking the manufacturer to do that,” says Martini.

If a manufacturer is developing a new herbal product, the onus is on them to provide the evidence that it is safe

Gino Martini, chief scientist at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

He adds that “if a manufacturer is developing a new herbal product, the onus is on them to provide the evidence that it is safe, whether by demonstrating they are using expert independent advice or carrying out additional toxicology testing to support that”.

“The onus is on them to prove it’s fit for purpose.”

But there are challenges to regulating this area more proactively, Martini says, namely the variability in potency and ingredients across different iterations of the same herbal supplement. One example of how complex this field can be is the decision by the Food Standards Agency in January 2019 to reclassify CBD products as novel foods, thereby awarding them tighter controls over manufacturers, he explains[12].

A UK government-commissioned report published in June 2021 addresses this complexity and creating smarter regulation around nutraceuticals — a term that includes both functional foods and nutritional supplements[13]. The report from the Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform argues that “traditional silos of regulatory classification are being challenged by the pace of bioscience” and calls for a system that better reflects the relationship between pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals.

Improving awareness

For Gavins, another way to mitigate the risks of herb–drug interactions is for improved awareness and education of primary care providers.

“As part of their continuing professional development, pharmacists, doctors and nurses should actively increase their awareness of the risks associated with herbal and food–drug interactions,” she recommends.

“Healthcare professionals should be aware of the most common interactions, especially for at-risk patients and patients taking drugs that act on the central nervous or cardiovascular systems.”

In addition, she says, healthcare providers should check relevant resources, including Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions, when prescribing and supplying drugs[5].

Patients must inform their doctors and pharmacists when they are taking natural remedies, herbal medicines or nutritional supplements

Gill Jenkins, a GP and adviser at the Health and Food Supplements Information Service

Finally, there must also be greater onus on patients to disclose relevant information about their diets — including any herbal supplements they take.

“We need more studies, and better information for clinicians and pharmacists,” says Jenkins.

“But the bottom line is that patients must inform their doctors and pharmacists when they are taking natural remedies, herbal medicines or nutritional supplements, and must themselves take responsibility for reading up about the risks.

“The study of drug–drug, food–drug and herb–drug interactions, and of genetic factors affecting pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, is expected to improve drug safety and will enable individualised drug therapy, but this is a long way off.”

Until then, we need to pay far greater attention to the potential risks of these seemingly innocuous herbal supplements.

- 1Europe Herbal Supplements Market. Market Data Forecast. 2021.https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/europe-herbal-supplements-market (accessed 20 Jul 2021).

- 2THE VITAMIN D FACTOR: BRITS SPEND ALMOST £500 MILLION ON VITAMINS AND SUPPLEMENTS. Mintel. 2020.https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/beauty-and-personal-care/the-vitamin-d-factor-brits-spend-almost-500-million-on-vitamins-and-supplements (accessed 20 Jul 2021).

- 3Koziolek M, Alcaro S, Augustijns P, et al. The mechanisms of pharmacokinetic food-drug interactions – A perspective from the UNGAP group. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2019;134:31–59. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.003

- 4Mohn E, Kern H, Saltzman E, et al. Evidence of Drug–Nutrient Interactions with Chronic Use of Commonly Prescribed Medications: An Update. Pharmaceutics 2018;10:36. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics10010036

- 5Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. MedicinesComplete. https://about.medicinescomplete.com/publication/stockleys-herbal-medicines-interactions-2/ (accessed 21 Jul 2021).

- 6FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2017.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-low-magnesium-levels-can-be-associated-long-term-use-proton-pump (accessed 21 Jul 2021).

- 7Does St John’s Wort interact with Emergency Hormonal Contraception? Specialist Pharmacy Services. 2020.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/does-st-johnos-wort-interact-with-emergency-hormonal-contraception/ (accessed 20 Jul 2021).

- 8St John’s wort: interaction with hormonal contraceptives, including implants. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . 2014.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/st-john-s-wort-interaction-with-hormonal-contraceptives-including-implants (accessed 20 Jul 2021).

- 9Deutch MR, Grimm D, Wehland M, et al. Bioactive Candy: Effects of Licorice on the Cardiovascular System. Foods 2019;8:495. doi:10.3390/foods8100495

- 10Zhi-Xu H, Chia T, Shu-Feng Z. Clinical Herb-Drug Interactions as a Safety Concern in Pharmacotherapy. J Pharmacol Drug Metab 2014;1:1–3.http://www.jscholaronline.org/full-text/JPDM/101/Clinical-Herb-Drug-Interactions-as-a-Safety-Concern-in-Pharmacotherapy.php

- 11Awortwe C, Makiwane M, Reuter H, et al. Critical evaluation of causality assessment of herb-drug interactions in patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:679–93. doi:10.1111/bcp.13490

- 12Cannabidiol (CBD) guidance. Food Standards Agency. 2021.https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/cannabidiol-cbd (accessed 20 Jul 2021).

- 13Duncan Smith SI, Villiers T, Freeman G. Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform independent report. GOV.UK. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/taskforce-on-innovation-growth-and-regulatory-reform-independent-report (accessed 20 Jul 2021).