“We’re on the cusp of something really exciting,” says Jilly Croasdale, head of radiopharmacy at Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust.

Over the past five years, there has been a surge in new radiopharmaceutical trials for treating cancer, which gives hope for improved treatment and survival rates. There is also renewed development from major pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, Eli Lilly, BMS, AstraZeneca and Sanofi, adding at least US$10bn in radiopharma-focused investments and acquisitions. In November 2025, the UK government assigned £9.9m in funding to a project that recycles nuclear fuel into new cancer radiotherapies.

Ebrahim Delpassand, founder and chief executive of RadioMedix — a radiopharmaceutical oncology company based in Houston, Texas — thinks they’re capitalising on a growing trend. “They have seen the potential for radiopharmaceuticals, and they want to be part of it,” he says.

Delpassand says the new generation of radiopharmaceuticals is addressing unmet needs in oncology and expanding options for the treatment of neuroendocrine and prostate cancers. “In the next five years, we should have breakthroughs in the area of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and hopefully brain tumours [glioblastoma multiforme],” he adds.

Companies are also developing radiopharmaceuticals to treat ovarian cancer, sarcomas, triple-negative breast cancer and lung cancers when conventional approaches are not working.

However, the UK is already lagging behind some European countries in access to these therapies. Given predictions of an oncoming wave of therapies, the UK could fall even further behind countries that are more willing to fund them and have better infrastructure.

Unique to radiopharmaceuticals, funding is not only needed for the drugs but to create the infrastructure of hospital radiopharmacies necessary for administering these treatments. Here, experts worry the UK is also failing to ensure it has enough capacity for the future.

A magic bullet

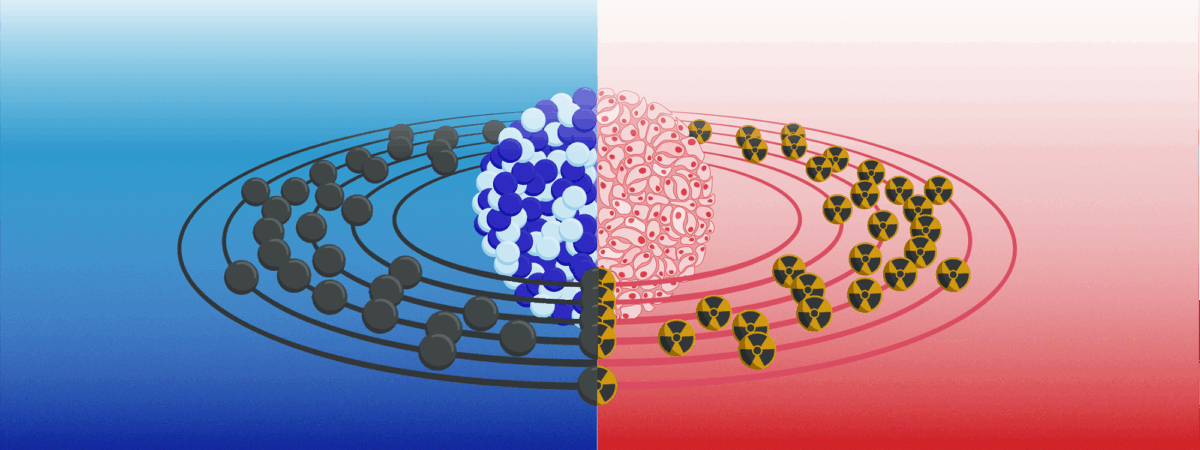

Molecular radiotherapies are drugs containing a radioisotope attached to a cancer-targeting molecule known as a ligand. They work like a “magic bullet”, says Croasdale. Delivered orally or intravenously, they’ll “be taken up into the primary and any metastatic lesions as well, because they all have the same receptors”, she explains.

The ligands bind to cancer cell receptors exclusively to deliver their deadly dose of radiation while limiting healthy tissue damage. “The side effect profile is probably better than external beam radiation,” Croasdale adds, although she notes that there will still be unwanted effects such as extreme dry-mouth.

This surge of new radiopharmaceutical drugs, such as Pluvicto (Lu-177 vipivotide tetraxetan; Novartis) for prostate cancer and lutetium dotatate (Lutathera; Novartis) for neuroendocrine tumours (see ‘New therapies’) is down to multiple factors. The introduction of positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in the 1990s encouraged new interest in novel radio isotopes, which are starting to bear fruit as new therapies now. The burgeoning discovery of cell receptors has also provided ways to exclusively target cancer cells, radiopharmacists say.

Treatment and diagnosis combined

Theragnostics is a personalised medicine approach, which combines both diagnosis and therapy into a single intervention, often using radiopharmaceuticals. Here, short-lived targeted radiotracers are used to diagnostically image specific cancer cells before delivering targeted therapeutic radiation to kill the same cells.

PET imaging provides better sensitivity than previous imaging methods and has enabled drug developers to design theragnostics, allowing quantitative diagnostic imaging to select suitable patients to receive these expensive molecular radiotherapies.

You could see tumours that you couldn’t see before, you could see metastases and before that, you really weren’t able to do that

Maggie Cooper, PET chemistry operations manager for the Positron Emitting Radiopharmaceutical Laboratory at King’s College London

Maggie Cooper, PET chemistry operations manager for the Positron Emitting Radiopharmaceutical Laboratory at King’s College London, says that around 15 years ago, some hospital radiopharmacies began making their own gallium-68 (Ga-68) radiotracers for theragnostics, which give exceptionally good images.

“You could see tumours that you couldn’t see before, you could see metastases and before that, you really weren’t able to do that,” she explains. It only has a half-life (i.e. the time for half of it to decay) of 68 minutes, so it has to be made close to patients and used quickly.

Not every radiopharmacy will have the capacity to produce Ga-68 products. Owing to their relatively high-energy emissions, molecules that include Ga-68 are made in contained workstations known as isolators that have thick shielded doors at the front: 50mm of lead is common to block the radioactivity.

The Ga-68 is produced from a ‘generator’ consisting of a column of germanium-68 — the long-lived parent isotope — immobilised on a matrix. As it decays, radioactive gallium is washed out each day to create gallium-labelled cancer diagnostic products for patients.

At a cost of about £80,000, Ga-68 generator access in the UK is “very patchy”, says Croasdale. There are seven in London and a similar number for the whole of the rest of the country. “It is definitely improving. But there’s still some way to go,” she adds.

The alternative diagnostic radio isotope is fluorine-18 (F-18), which has the advantage of a longer half-life of 110 minutes. “You can actually transport it a reasonable distance to external sites to hospitals that don’t have gallium on site,” says Cooper. The radioisotope is made in a cyclotron — a particle accelerator that bombards oxygen-18-enriched water with high-energy protons) — leading to F-18, which makes it more expensive. Ga-68, which can be made on-site, is sometimes a more flexible option, especially for early-stage clinical trials. For either diagnostic, time is still of the essence for radiopharmacies.

“You really have to move very quickly and that is a challenge,” says Cooper.

New therapies

One of the first theragnostic radiopharmaceuticals — and the only one to be fully commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) — is lutetium dotatate. It is used to treat inoperable or metastatic neuroendocrine tumours (NET), which are cancers that form in nerve and hormone producing cells in the lungs, gut and pancreas, and over-express the somatostatin receptor (SSTR). A radioisotope is bound to an eight-amino-acid synthetic somatostatin-mimic, known as TATE, connected by the chelating agent dodecane tetraacetic acid (DOTA), which together are known as DOTA-TATE. For diagnostics, the radioisotope is Ga-68 or F-18; however, the therapeutic uses lutetium-177 (Lu-177), which emits beta radiation (i.e. high-energy electrons) that can destroy cancerous cells.

“Dota [dotatate] is well established,” says Croasdale, but because there are relatively few NET cases, its impact has been small. The therapy that “made the real difference”, she says, was a theragnostic pair that targets prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) on prostate cancer cells. Pluvicto was approved by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in 2022 for the treatment of advanced PSMA-positive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and significantly improves survival and quality of life after other treatments fail. Its half-life of 6.7 days makes distribution easier.

Joseline Tan, head of radiopharmacy at the Royal Marsden Hospital, explains that several trials are trying to move clinical use of lutetium PSMA much earlier rather than waiting until patients have failed all other options1. One company that is working towards this is Curium Pharma. Ruairi O’Donnell, general manager at Curium UK and Ireland, says: “Ultimately, you’d like to see these being second-line therapies, so that when you’ve had a positive PSMA scan, you go straight on to these therapies and avoid chemotherapy, which is toxic to the entire body.” Curium has its own F-18 PSMA diagnostic, known as Pylclari, and is developing a companion Lu-177 therapeutic.

However, PSMA therapies are not yet available on the NHS. “It’s extremely expensive, and I don’t think the cost benefit has been sufficient to convince NICE yet,” says Croasdale. This means that across the UK, patients must pay for it themselves unless they are taking part in a clinical trial. Patient groups report that private clinics charge around £15,000 per dose, with a typical course being four to six infusions. It is not successful for everyone, Croasdale says, but can be lifesaving for some.

“I speak to patients all the time who have had these treatments, and years down the line their disease has still not progressed,” she explains. Results from a pivotal clinical trial, published in 2021, showed a median overall survival benefit of about four months for patients who received Lu-PSMA-617 and standard care compared with standard care alone (around 15.3 months versus 11.3 months)2.

Alpha emitters are on their way

RadioMedix and other companies are also developing new types of ligands, such as antibody fragments and alpha emitter radioisotopes. Alpha emitters decay by releasing heavy alpha particles (i.e. two protons and two neutrons) instead of the beta electrons emitted by Lu-177. They produce several hundred times more energy than beta emitters but have a shorter 50–100µm range. This means they cause deadly double-strand breaks in DNA that kill targeted cancer cells but cause minimal damage further away.

RadioMedix is concentrating on lead-212 (Pb-212) because its half-life of 10.6 hours matches the circulating time of their ligands. Pb-212 also emits beta particles, so it has a hybrid action. In 2024, RadioMedix and Orano Med licensed AlphaMedix (Pb-212 DOTAMTATE) to Sanofi. Following successful phase II trials, this therapy is now entering phase III trials for treating NETs. Delpassand says they are seeing some exciting secondary benefits from Pb-212 radiotherapies. Their killing selectivity seems to leave immune cells intact, which then later mount an immune response to fight the cancer.

“More than six months after the last treatment, patients start showing [tumour shrinkage] responses,” says Delpassand, which after that length of time cannot be directly related to the radiation itself.

Pressure on radiopharmacy provision in the UK

Novartis continues to generate trial evidence that it hopes will persuade NICE to fund Pluvicto in future. If it is approved, there will be a huge pool of eligible prostate cancer patients. Croasdale says she has concerns about capacity to deal with demand. “Once it gets NICE approval, people are going to want to have it,” she says, explaining that UK hospital radiopharmacies are not ready for the added workload. “There’s a lot that needs to be done in terms of expanding our workforce, looking at our infrastructure and the layout of our departments.”

If you come back in ten years, you’ll see a different landscape in terms of nuclear medicine therapy

Ruairi O’Donnell, general manager at Curium UK and Ireland

More hospital radiopharmacies would need expensive Ga-68 generators, as well as trained staff to manufacture the short-lived diagnostic agents needed to check if a patient is suitable for the radiotherapy. Highly trained radiopharmacists, who not only manufacture the agents but also validate the purity of the product and oversee quality control are also needed.

“The amount of work to set it up is quite extensive,” says Cooper. “We don’t have all those resources of a company like Glaxo or Novartis, but yet, we still have to do the same amount of validation work to show that the product can be made every single time to the right quality.”

The difficulty of the task has led to some closures. In 2023, the University Hospital of Wales radiopharmacy service was closed following an MHRA inspection and regulatory concerns. “On one hand, MHRA are closing down radiopharmacies. On the other hand, there isn’t an adequate supply of product in the market,” says O’Donnell. Croasdale, who chairs the British Nuclear Medicine Society’s UK Molecular Radiotherapy group, is drawing up an action plan to improve current provision. The Welsh government is also planning a new radiopharmacy facility in Newport, Wales, that is due to open in 2026.

A central issue for any expansion will be training more radiopharmacists. Cooper says the current lack of expertise in the UK is a ‘chicken and egg’ situation “because there aren’t the opportunities, they don’t attract people into that field”.

Getting into radiopharmacy was a happy accident for Croasdale, who was offered a radiopharmacy job early in her pharmacy career and found it absorbing. Cooper had a similar experience after spending only one day in a radiopharmacy lab. Tan was in an oncology pharmacy role when a colleague left the radiopharmacy lab – she was asked to step in and hasn’t looked back. “You will probably find that a lot of people come to this field through this route,” she says.

Croasdale adds that radiopharmacies need much more investment, but hospitals have been reluctant to invest in a relatively hidden service. “Why would you give another member of staff to the radiopharmacy? If you’re short in A&E, you put staff in A&E first.”

Nevertheless, some hospitals are expanding their radiopharmacies. Tan says that Royal Marsden Hospital is planning to recruit another 7 staff to add to the current 20 staff in her radiopharmacy to meet current internal demand to supply radiopharmaceuticals for clinical use, including ongoing trials.

Although not everyone working in radiopharmacy has a pharmacy background, “we’re always trying to encourage pharmacists to join this sector”, Cooper says. She also believes the lack of qualified pharmacists in this field is attributable to the decreased focus on chemical manufacturing in current pharmacy degrees and a greater emphasis on clinical pharmacy. Although the job needs manufacturing know-how, Cooper believes the next generation of theragnostics will need pharmacists to be more clinically involved. “As a pharmacist, you’re always checking, is this the appropriate drug for this particular patient? Is it the right dose? Is the patient fit for the treatment?” she explains.

For interested pharmacists, the formal route is through the NHS Scientist Training Programme in clinical pharmaceutical science, which is a three-year apprenticeship in a hospital lab with part-time study. The Pharmaceutical Technology and Quality Assurance (PTQA) masters programme is another route; however, Croasdale says these schemes are competitive.

In the meantime, the potential for molecular radiotherapies in cancer continues to grow. “There are also trials coming through for breast cancer, so that will be a huge patient pull,” says Tan3. Plus Cooper says they are looking into using molecular radiotherapies in more standard patient management. She is currently involved in a trial to see whether uptake of a specific radio tracer before and after treatment can predict chemotherapy outcomes.

“If you come back in ten years, you’ll see a different landscape in terms of nuclear medicine therapy,” says O’Donnell.

- This article was amended on 20 January 2026 to clarify that both RadioMedix and Orano Med licensed AlphaMedix to Sanofi in 2024

- 1.Wang J, Yuan H, Xu J, Yang C. Advances in PSMA-Targeted Radionuclide Therapy for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. CMAR. 2025;Volume 17:1859-1869. doi:10.2147/cmar.s538367

- 2.Rohith G. VISION trial. Indian Journal of Urology. 2021;37(4):372-373. doi:10.4103/iju.iju_292_21

- 3.Rahmati H, Mousavi SM, Souri Z, Farzipour S, Tavani AE, Jalali-Zefrei F. New Radiopharmaceutical Tracers in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. ACAMC. 2025;25(16):1198-1217. doi:10.2174/0118715206357095250306051714