Science Photo Library

Steve Bradley, a 52-year-old Londoner, was diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) in 2008. Nothing had prepared him for the news. “I was stunned,” he says. Bradley was working for London-based television broadcaster ITV as a projects engineer at the time. “Why should I have TB? There’s nothing like I’m going to India, or Pakistan or South Africa.” His best guess is that he picked it up on public transport. “I’ve been [travelling] on the tube for 30 years. I’m coughed and spluttered all over.”

It was only after Bradley was admitted to intensive care that his doctors made the diagnosis and put him on standard therapy for TB. Bradley was unlucky. Within four weeks of being put on medication he was registered blind, owing to an adverse reaction to ethambutol, one of his anti-TB drugs.

He blames his predicament on poor monitoring and a lack of awareness of TB and the drugs that are used to treat it. “I never had a TB nurse even,” he says. Nowadays, he believes things are better but worries that services are still patchy.

Bradley is typical of TB patients in the UK in that he is from the capital. Almost 40% of all TB cases in England are diagnosed in London. Some parts of the city have higher incidence rates than countries such as Rwanda, Algeria, and Iraq.

London is at particular risk predominantly because of its demographics. Many people from all over the world are living side by side, often in crowded conditions. The good news is that, probably owing to a combination of changing demographics and new strategies to tackle the disease, TB rates may finally be under control. “For about 20 years they were going up and in the last three years we’ve seen them plateau and come down,” says Angela Houston, a consultant in infection at London’s St George’s Hospital.

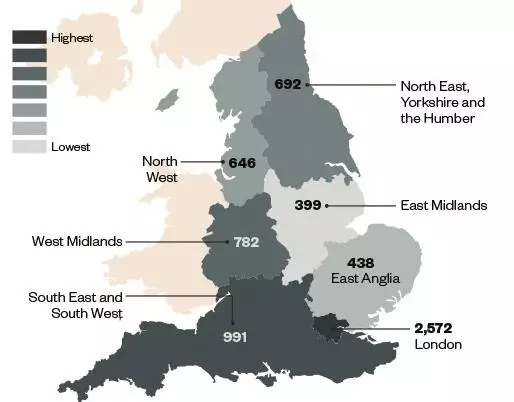

TB burden in England

Source: Public Health England

In 2014, London accounted for the highest proportion of tuberculosis (TB) cases notified to the seven TB control boards in England (39.4%)

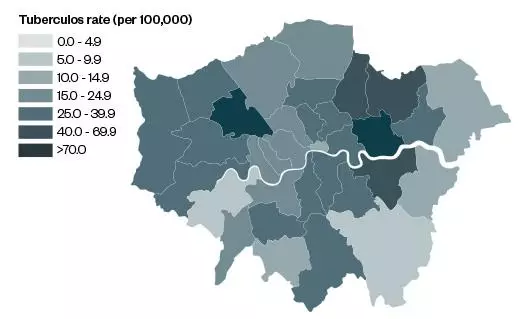

TB rates in the City

Source: Public Health England

Some areas of London have incidence rates higher than Rwanda, Algeria and Iraq. The map shows three-year average TB rates by local authority, 2012–2014

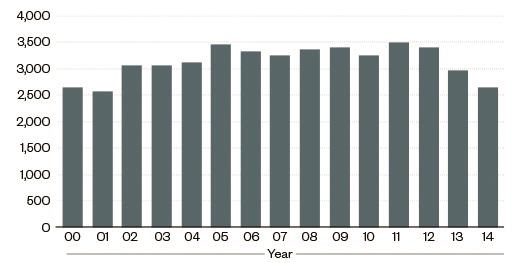

TB cases begin to decline

Source: Public Health England

New strategies to tackle tuberculosis are thought to have contributed to an annual decline in cases in London since a peak of 3,489 in 2011

The drugs Bradley was given are old and tough to take. “The treatment has not changed for about 40 years,” acknowledges Onn Kon, a respiratory physician who heads up the TB service at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in London.

Two new drugs have recently been licensed for multi-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) but the mainstay of first-line therapy is isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol, all of which can have debilitating side effects. Patients are on a cocktail of some combination of these drugs for six months, and it can be hard to get them to stick it out, especially if they have other, social, issues. And most have: Bradley is not typical of TB patients in this respect.

TB is a marker of the social deprivation in certain communities

A Public Health England report from October 2015, ‘Tackling TB in London’, aimed to shed light on the problem and bring it to the forefront of the political agenda[1]

. To get TB in London under control, the report contends, both social and clinical factors must be dealt with. “[TB] is a marker of the social deprivation in certain communities,” says Onkar Sahota, a London Assembly Member for the Labour Party and a general practitioner, and one of the authors of the report.

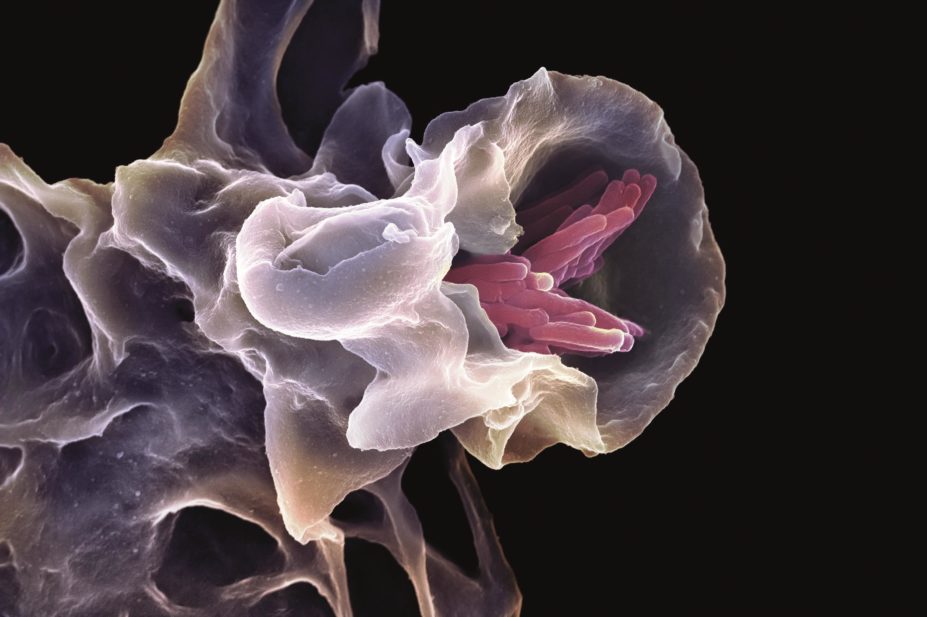

The bug

TB is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bug at least as old as mankind. “It’s survived this long by having mechanisms to hide and evade our immune system,” says Houston. And one of the ways it can do that is by lying dormant; only reactivating when its host’s immune system is down. This is known as latent TB.

More than 80% of cases of TB in London occur in people who were born abroad, and the majority of these will have entered the country with latent TB that then reactivated at some point after their arrival. Since 2005, in order to get a visa to enter the UK you need to have been screened to show you are free of TB. However, the screens, which rely on chest X-rays and sputum samples, will only pick up active pulmonary TB and will not pick up latent TB or TB elsewhere in the body.

High rates of TB are also seen in homeless populations, people in prison, people with drug abuse problems and those with other chronic conditions, such as HIV. Identifying these people can be difficult. One service, known as Find & Treat, has led the way by going to areas where there are likely to be high numbers of people with the disease and offering a free screening service. “Find & Treat specifically targets groups that find it much harder to engage with conventional TB services,” says Kon, who used to be on the Department of Health Find & Treat Steering Committee.

Once you have identified people with TB, it is important to help get them through treatment. One of the strategies that seems to be making an impact is directly observed therapy (DOT). This is where a TB nurse goes to visit a patient and observes them taking their treatment. Only a subset of patients need this kind of intensive support; some will need none, some may be asked to come into the clinic for DOT. Pharmacies can also offer the service.

Trevor Hart, a DOT outreach worker based at the Whittington Hospital in London, believes this approach works because “there’s nothing quite like the personal face-to-face relationship in terms of engaging someone and keeping them engaged”. He meets patients at places most convenient for them, no matter if that changes from appointment to appointment or if it is on a street corner somewhere. He says that in four years of being in the role he has lost less than a handful of patients to follow-up.

There’s nothing quite like the personal face-to-face relationship in terms of engaging someone and keeping them engaged

Helen Booth, a consultant in thoracic medicine at University College London, who works alongside Hart, agrees that DOT works but concedes that it is expensive. She is part of a research team comparing the outcomes of using virtually observed therapy (VOT) with standard DOT. With VOT, patients are given a smartphone with an app on it that they can use to video themselves taking their medication. The clip then goes to a team of TB nurses, who report back if they are not receiving them. She believes this will work for most, but not all, patients. “There will always be a role for [DOT outreach workers] as well because there will be some people who can’t use [VOT] or won’t use it for whatever reason,” Booth explains.

Catherine Cosgrove (left), a consultant in infectious diseases and acute medicine, and Angela Houston, a consultant in infection, work together at London’s St George’s Hospital

An alternative approach to meeting the patient where they want to be met is keeping the patient in one place by securing stable accommodation for them. Catherine Cosgrove, a consultant in infectious diseases and acute medicine who works alongside Houston at St George’s Hospital, says that if she could change one thing about TB services in London, it would be to provide accommodation for patients undergoing treatment, “a place of safety for them to have their therapy”.

A scheme pioneered by London’s Homerton University Hospital does just this. It has an agreement with the local authority to house patients with TB who are homeless and have no access to benefits, usually because of their immigration status. Since 2008, the scheme has found accommodation for 36 TB patients from 25 different countries, and patients can be in their new homes within a day or two of being referred. “We do not have to hunt for funding, which makes this TB housing scheme very different from any others in London,” says Sue Collinson, a TB caseworker at Homerton. And it looks like it’s working. “We have not had a patient lost to follow-up since we began the housing scheme,” she says.

Encountering resistance

The risk of losing patients to follow-up is that if they do not complete their medication it increases the chances of the bacteria developing resistance. Although rates of MDR-TB in London remain stable and relatively low, it is still a problem, as St George’s recently found out. “We’ve had a number of cases of extremely drug-resistant TB,” says Cosgrove.

This means developing new drugs to tackle TB has to be a priority. But M. tuberculosis is a particularly challenging bug to treat. “It’s hard for antibiotics to get through the cell wall,” says Houston. And, she adds, “it can become resistant very easily to a drug if it’s not bombarded by lots of drugs at once”.

[TB] can become resistant very easily to a drug if it’s not bombarded by lots of drugs at once

Two new drugs were licensed for MDR-TB in the UK in 2014: delamanid (Deltyba) and bedaquiline (Sirturo). Houston describes them as “an incredibly important step forward” but warns that they are not perfect. Because these are drugs of last resort — used only when other standard treatments have failed — clinicians are still in the early stages of collecting data, but both seem to carry risks for the heart and liver function.

“The other issue is that you can get resistance to them as well,” Cosgrove points out. Patients with MDR-TB can expect to be on some combination of anti-TB treatment for two years or longer.

Kon believes these new drugs are the result of a change in approach by drug companies over the past ten years. “Prior to that, no one was really interested,” he says. But now there has been more of a focus on TB drug development, partly driven by The Global Alliance for TB Drug Development (TB Alliance), a not-for-profit organisation funded by a combination of governmental bodies and charities such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This has led, Kon says, to a more targeted approach: delaminid and bedaquiline were custom-built to treat TB.

Nonetheless, the rate of progress is slow. In February 2015, the TB Alliance announced that a drug it has been developing, TBA-354, was entering human trials. It was the first new TB drug candidate to begin a phase I clinical trial since 2009.

Another strategy scientists are looking at is finding new combinations of old drugs, some of which may not have been used in TB before, to develop a more patient-friendly drug regimen for standard TB. “Getting a better treatment for a shorter period of time is the holy grail,” says Booth.

Getting a better treatment for a shorter period of time is the holy grail

However, there has been a setback. A phase III trial looking at swapping in moxifloxacin for either ethambutol or isoniazid in the standard TB regimen hoped to show that this could reduce treatment duration to four months. But the results were negative[2]

. Researchers are now looking at how to change their approach to trial design “so you don’t spend five years and thousands of pounds just to get a no answer at the end”, says Booth.

Looking for a vaccine for TB is faring no better. “The first big [vaccine] hope was published a couple of years ago and unfortunately it didn’t have any efficacy,” says Kon. This leaves the BCG vaccine, first used in humans in 1921, which has limited efficacy in adults but a 60–80% protective efficacy against severe forms of TB in children. Even then, despite the fact that it is universally recommended for all babies born in London, the service is not universally commissioned, especially in boroughs with relatively low TB rates.

Recent advances in diagnostics have been more promising. GeneXpert is a molecular test that allows doctors to search for mycobacterial DNA rather than waiting to culture a sample. “The biggest breakthrough we’ve had in the past five years is the routine use of GeneXpert,” Houston says. Not only does it confirm whether or not somebody has TB, it also indicates whether the strain they have is resistant to rifampicin, a useful indicator of resistance to other drugs.

Even more exciting is the possibility of using whole genome sequencing (WGS) to diagnose TB. Since WGS looks at the whole sequence of the bacterial DNA rather than just searching for bits of it, it offers the possibility of a comprehensive readout of drug sensitivities. New research shows it may even be cheaper than routine diagnostics, coming in at £481 per culture-positive specimen versus £518 for standard procedures[3]

.

The team at St George’s has been running its own research on WGS, and used it in a recent set of patients with drug-resistant TB. Not only did it help guide treatment, it also helped with contact tracing — finding other people who are infected with the same strain of bacteria. “If you know that somebody’s got exactly the same bug as somebody else on your books, you can immediately start looking to see what their link is and then do contact tracing around that area,” explains Cosgrove.

Hiding in plain sight

Onn Kon, a respiratory physician who heads up the TB service at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in London, says active disease is only the tip of the iceberg

All of these approaches are focused on those who have active disease. “We have this big iceberg under the water which is the latent TB,” remarks Kon. Testing for latent TB has become easier since the development of interferon-γ release assays (IGRAs), something Kon has been involved with. IGRAs work by mixing a sample of blood with M. tuberculosis antigens: if a person has previously been infected by the bug, their white blood cells will release interferon-γ.

Previously, exposure to TB had to be ascertained using a tuberculin, or Mantoux, skin test, which requires injecting antigen into the skin and then waiting for 48-72 hours before ‘reading’ the test. With IGRAs, “you just take a blood test, you don’t need to do one screen and then bring everybody back to have it read”, says Kon. What is more, the skin test can be positive if somebody has had the BCG vaccination. “The blood test is more specific,” Kon says.

Public Health England is now rolling out a strategy to test for latent TB among migrants from high-incidence countries who have arrived in the past five years. “I think that probably will make a difference,” says Booth, although she points out that some areas are ahead of others in implementing the new policy.

Variability of services is one of the major problems with TB treatment across London. Kon has experience of this within his own trust, Imperial. The trust comprises St Mary’s, Charing Cross and Hammersmith hospitals. Each hospital has its own TB clinic and, until recently, each provided a slightly different service and had different outcomes. Now they share one nursing team and have the same protocols. “It’s just that we’ve got three clinics but effectively now we have the same set up,” Kon says.

This variability is true across the UK. “You can end up in parts of the UK and get a completely different service,” Kon points out. Which is why when Public Health England published a new TB strategy for 2015 to 2020[4]

, one of its recommendations was the formation of so-called TB control boards to coordinate treatment across seven different areas in England, of which London is one.

You can end up in parts of the UK and get a completely different service

Most people believe that a more coordinated TB strategy is essential to getting on top of the disease, but there is disagreement about how much to centralise. Booth uses stroke as a successful example of centralisation: “There are five centres in London that do acute stroke and the outcomes have improved hugely.” But others say this kind of approach should be reserved for drug-resistant cases. Cosgrove emphasises the need for people to have access to local services; the key, she believes, is making it as easy as possible for patients to get treated. “Often these are young people with either caring roles or they’ve got jobs to do,” she points out.

Most importantly, London must remain vigilant. As Sahota puts it: “We keep thinking that this is a disease of the last century but it’s also a disease of today and of tomorrow.”

References

[1] Sahota O, Boff A, Malthouse K et al. Tackling TB in London . London Assembly, 2015.

[2] Gillespie SH, Crook AM, McHugh TD et al. Four-month moxifloxacin-based regimens for drug-sensitive tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2014;371:1577–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407426

[3] Pankhurst LJ, del Ojo Elias C, Votintseva AA et al. Rapid, comprehensive, and affordable mycobacterial diagnosis with whole-genome sequencing: a prospective study. The Lancet 2016;4:49–58. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00466-X

[4] Public Health England. Collaborative Tuberculosis Strategy for England 2015 to 2020. Public Health England/NHS England, 2015.