Andrea Ucini

Regular users of social media platforms will be familiar with online health and lifestyle ‘influencers’, with millions of followers posting a range of content, from ‘what I eat in a day’ videos to personal trainers posting optimal workouts for fat burning. Online, it seems there is always a quick fix to get the ‘perfect’ body.

In most cases, these posts are usually harmless — perhaps even motivational — to those looking to lose weight, but there remains concern that some of the information around diet products promoted on social media is falling into the wrong hands and causing serious harm, particularly among younger people.

Many social media companies have promised to prevent users aged under 18 years from being able to access information about diet treatments on their platforms. Instagram and its owner, Facebook, tightened their rules on this in 2019, when it was announced that both platforms would start to hide posts promoting cosmetic surgery and diet products from users aged under 18 years in a bid to “reduce the pressure” that people can sometimes feel as a result of social media.

However, the fastest growing platform among young people is TikTok, which was launched in the international market in 2017 by Chinese company ByteDance. Its popularity is owed, at least in part, to its algorithm, which learns from indicated preferences and content that the user has previously ‘liked’. In many cases, TikTok videos are of users lip-syncing, dancing or acting out comedy sketches, but it also provides a platform for individuals or companies who are looking to promote particular products, such as diet pills.

TikTok’s ‘Community guidelines’ prohibit the promotion, normalisation or glorification of activities that could lead to suicide, self-harm or eating disorders, warning that any such content will be removed if they find it, using a combination of technology and thousands of safety professionals[1].

In February 2022, TikTok strengthened its policies further in a range of areas, including the removal of content depicting disordered eating, “as we understand that people can struggle with unhealthy eating patterns and behaviour without having an eating disorder diagnosis”[2].

As well as removing content, the app also provides resources to support its community’s wellbeing, including the addition of permanent public service announcements on certain hashtags — such as #whatieatinaday — to increase awareness and provide support.

However, in order to test whether young people were being protected from the promotion of diet pills on the platform, The Pharmaceutical Journal set up an experiment by registering on the platform as a female born in 2006.

Slipping through the gaps

Starting with a completely clear search history on the platform, we explored content under the hashtag ‘diet pills’. At the time of the investigation, in August 2022, the hashtag itself had 10 million views, and the most popular post had more than 20,000 ‘likes’ and more than 1,000 shares.

A closer analysis of the 100 most popular videos — collated during a single 90-minute sitting — revealed that nearly a third (31%) were actively promoting the use of diet pills for weight loss.

In the posts, users said that the pills helped to “curb” their appetite, increase their energy levels and their body temperature; all of which helped them lose substantial amounts of weight.

More shockingly, although the majority of these posts referred to ‘diet pills’ as an umbrella term, more than a quarter (26%) were promoting a specific named prescription-only medication, such as drugs for epilepsy or addiction.

It is illegal for a pharmaceutical company to advertise prescription-only medicines to the general public, at any age, on social media sites, but the same standards do not apply to users of these platforms, in a loophole that could be potentially damaging to the mental and physical wellbeing of users[3,4].

Our fictional 16-year-old user was able to view several posts promoting the use of prescription-only medication for weight loss, the most common included phentermine, an appetite suppressant, and Acxion Fentermina; a phentermine-based drug available on prescription in Mexico, although it is also available online to purchase without a prescription, requiring only a quick search on Google.

Other prescription drugs mentioned under the hashtag #dietpills included a combination of naltrexone — a drug for treating alcohol and opioid addiction — and topiramate, an antiepileptic and migraine treatment (see Figure 1).

Diet claims that are unrealistic and not supported by evidence-based science on social media can be dangerous no matter what your age

A spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association

The commonly prescribed diabetes drug metformin and orlistat, sold over the counter in the UK under the brand name Alli and others, were also mentioned.

The posts ranged from daily video diaries of individuals taking the pills for weight loss; before and after weight loss images and videos; individuals selling diet pills via the platform; and videos explaining how to take diet pills.

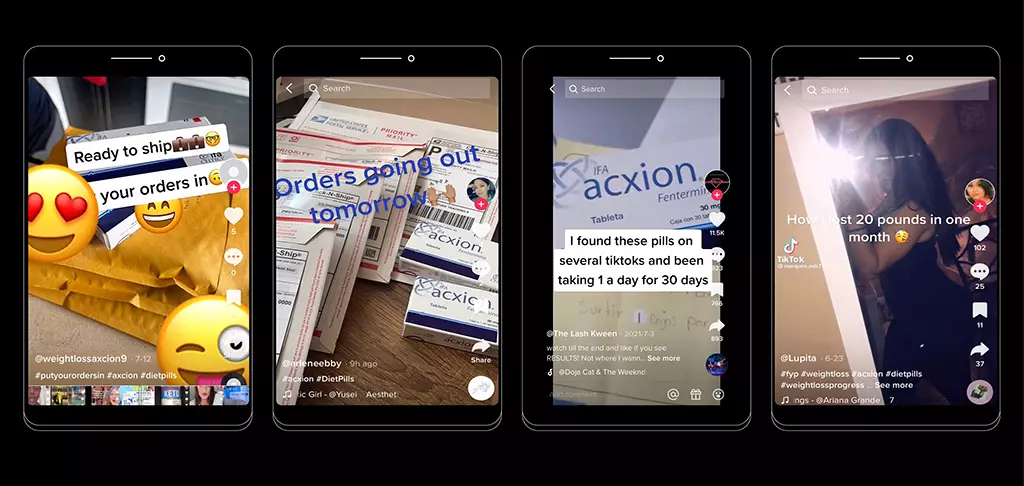

In many videos, there were claims of dramatic weight loss in relatively short periods of time, including one video that talked about “how I lost 20 pounds in one month” by taking Acxion Fentermina (see Figure 2).

Far left: The user discusses the action of naltrexone and topiramate and how they help to curb appetite weight loss and says she will update viewers on how she gets on (this is one in a series of videos);

Second from left: @kristenclark1970 discusses day 1 of taking PhenQ “the PhenQ seemed to give me energy…been thirsty all day so have been drinking a lot more water…a good first day”;

Second from right: @kristenclark1970 highlights how 19 days into taking PhenQ she has lost enough weight to fit into a dress she previously couldn’t zip up;

Far right: @kadythompson discusses how the ‘lean body system’ works saying the first product, ‘Trim’, inhibits fat storage and shrinks fat cells to enable the user to ‘lean out’, the second, ‘Burn’, is a thermogenic which curbs appetite and increases body temperature to ‘burn more calories’ and the third is an ‘aloe vera cleanse’ to help ‘detoxify the gut’, she then adds that the link to buy is ‘in her bio’

On the far left and second from left the posts are highlighting that they are selling the product to users;

On the right and second from right, the posts both say how they heard about the drug on TikTok and consequently bought them;

On the far right the user says she lost “20 pounds in one month” by taking Acxion Fentermina;

On the second from right the user says she has been taking one pill a day for 30 days after seeing them on “several TikToks” and has 11,500 likes

One person behind a TikTok post even said they had seen viral TikTok videos about diet pills and decided to buy some for themselves. “Some people say they’re kind of dangerous but I already bought them…” they said.

Healthcare experts say that this sort of information may cause real harm.

“Diet claims that are unrealistic and not supported by evidence-based science on social media can be dangerous no matter what your age,” a spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association (BDA) told The Pharmaceutical Journal. “But, for under 16s, they can have very real consequences.”

In March 2022, the NHS published data highlighting that more young people “than ever before” were receiving treatment for eating disorders[5]. Between April 2021 and December 2021, almost 10,000 children and younger people started treatment; an increase of a quarter compared to the same period in 2020. In response to these findings, experts recommended checking if the young person was accessing any pro-eating disorder websites or social media content.

Potential harm

The link between social media use and body image and eating concerns in young adults is a growing area of interest and concern among researchers.

A 2021 systematic review published in Cyberpsychology concluded that the time spent on social media was a determining factor in the development of an eating disorder as it “increases the exposure and visualisation of beauty references with which to compare oneself”[6].

This is completely inappropriate promotion of medication for the treatment of obesity in social media platforms that target young people

John Wilding, professor of medicine and honorary consultant physician in the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine at Aintree University Hospital

“This is completely inappropriate promotion of medication for the treatment of obesity in social media platforms that target young people,” says John Wilding, professor of medicine and honorary consultant physician in the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine at Aintree University Hospital.

“Most of these drugs — with the exception of orlistat, which can be prescribed or bought over the counter — are not approved for the treatment of obesity in the UK,” he adds. “Those containing phentermine can be legally prescribed for short-term use but only under very specific conditions. It remains a controlled drug.”

Wilding adds that these drugs could cause birth defects if a foetus was exposed to them. “Topiramate has never been approved for weight loss in the EU or the UK as it has some significant potential adverse events and may be teratogenic.

“Combining topiramate with naltrexone has not been tested in trials.”

Philip Newland-Jones, consultant pharmacist for diabetes and endocrinology at University Hospital Southampton Foundation Trust, said that the majority of the promoted drugs were either not recommended or licensed in the UK or had been withdrawn owing to side effects, including an increased risk of suicide.

“Phentermine drugs are not ideal… it’s effectively taking an amphetamine [that] has a risk itself with cardiac issues,” he continues.

The side effects of these medicines are significant. They can range from mild symptoms, such as headache, dry mouth, dizziness, nausea, vomiting and constipation, to more serious side effects, such as hypertension, drug dependence, abuse and withdrawal.

And, while many of the drugs talked about on the platform are not recommended or routinely prescribed for weight loss, this does not stop users from trying, and sometimes succeeding, in getting hold of them.

In May 2022, the Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia announced that there had been a shortage of the diabetes medication Ozempic (semaglutide; Novo Nordisk) after TikTok users began promoting it as an off-label weight loss treatment[7].

The news led experts to warn that health advice offered on social media apps, such as TikTok, should be interpreted with caution.

“It’s really easy to get hold of these things,” says Newland-Jones. “I have a colleague who has managed to purchase GLP-1 medicine [a class of medications utilised in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity] online without a prescription.”

Carel Le Roux, a metabolic medicine physician with an interest in obesity, agrees, but he has sympathy for users who might be struggling with their weight.

“It absolutely will drive them to get access,” he says.

“There’s a large number of young people under the age of 18 [years] that have the disease of obesity … [their] life is a lot harder than people that don’t have the disease of obesity. And hence, it’s not unreasonable for young people to look for a treatment, be that on TikTok or whatever mechanism they want to do so.

“But I think the problem is that they will be bitterly disappointed in the outcome.”

Le Roux explains that many studies have highlighted that although losing 25% body weight can positively impact quality of life in those who are obese, it may not improve body image.

It’s all about focusing on vulnerable people and trying to exploit them. That is wrong

Carel Le Roux, a metabolic medicine physician with an interest in obesity

“Advertising that weight loss is going to make you thin and happy … [is] just not factually correct. There’s no evidence to support that. And it’s false advertising and it’s all about focusing on vulnerable people and trying to exploit them. That is wrong.”

“I don’t have a problem with more information being available, I don’t have a problem with young people accessing information,” Le Roux says.

“What I have a problem with this is when the information is incorrect and unhelpful.”

What is clear is that people do act on this information.

Results from The Pharmaceutical Journal’s annual salary and satisfaction survey of almost 1,600 UK pharmacists revealed that almost 60% (910) of respondents have been asked about a medicine or product that a patient had heard about via social media. Of those who gave examples of the medicines asked about, 44 said they had been asked about weight loss or diet products, although the survey did not ask how old the patient was.

A solution?

Awareness is growing about the impact of social media on the mental health of young people — evidenced by an inquiry published in May 2022 carried out by the House of Commons’ digital, culture, media and sport committee on influencer culture[4].

The inquiry report highlighted that although community guidelines and standards from social media platforms were “consistent in prohibiting violent, dangerous, misleading or explicit content”, influencers still had a “high level of discretion” around posting content that falls between these lines but that may damage mental and physical wellbeing, such as diet products and cosmetic surgery.

“For example, [former Love Island contestant] Amy Hart told us that she turned down offers to promote diet products as many of her followers are children, and she [owed] it to the mums and the dads,” the report says.

“Many influencers do not exercise the same duty of care for their followers. Even if this were to change, identifying messages that are problematic is very challenging and triggering content can vary by person.”

Clearly there is a lot more work to be done by social media platforms to ensure these kinds of posts and unregulated adverts don’t get into the wrong hands

A spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association

“Clearly there is a lot more work to be done by social media platforms to ensure these kinds of posts and unregulated adverts don’t get into the wrong hands,” the BDA spokesperson adds.

“As an evidence-based and regulated profession, we need to continue to encourage the public to scrutinise what they see across all media and look out for unsubstantiated claims.

“We urge incorrect information [published on TikTok] to be reported to the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA).”

The ASA, which regulate the majority of adverts and promotions across media in England and Wales, is clear that adverts must not “irresponsibly exploit” the insecurities of children, young people and vulnerable groups, or contain anything likely to result in their physical or mental harm.

Its guidance also makes clear that adverts should not suggest that an individual’s happiness or emotional wellbeing depends on them conforming to an idealised gender stereotypical body shape.

“Ads for diet pills must not be directed at nor contain anything that is likely to appeal particularly to people who are [aged] under 18 [years],” a spokesperson for the ASA told The Pharmaceutical Journal.

“If the diet pills being advertised are prescription-only, this is not allowed under our rules and this applies to all advertising material, including in social media.

“We stand ready to consider any concerns that people may have about diet pill ads they have seen or heard.”

But this is not the case for content shared by users of social media, which relies on social media companies policing themselves. This may change in future years, with the Online Safety Bill going through parliament expected to extend UK regulation of “online harms” on social media platforms to Ofcom[8]. This bill was reportedly paused while a new prime minister was chosen.

The Pharmaceutical Journal approached TikTok to highlight the ongoing prevalence of posts on the platform promoting diet pills.

A spokesperson for the platform responded saying that TikTok “care[s] deeply about the health and wellbeing of our community”.

“Our Community Guidelines make clear that we do not allow the promotion or trade of controlled substances, including prescription weight loss medication, and we will remove content that violates these policies,” the spokesperson added.

The platform did take action to review the videos we had found and remove any that that were found to be selling controlled substances or that were promoting dangerous weight loss behaviour.

The diet pill hashtag was also reviewed and TikTok removed multiple accounts that were selling prescription weight loss medication.

While some of the posts highlighted by The Pharmaceutical Journal do appear to have been removed by the site, several still remain on the platform, suggesting that there is some way to go to protect young people entirely from this type of potentially harmful content and to spread the word about the impact of these posts to those creating them.

“I do support use of medication to help people with obesity lose weight and keep it off, but this should always be under medical supervision and supported by appropriate help with diet, activity and behavioural change,” concludes Wilding.

“I do not agree with the promotion of potentially unsafe, or unproven treatments via social media.”

- 1Community Guidelines. TikTok. 2022.https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines?lang=en (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

- 2Strengthening our policies to promote safety, security, and well-being on TikTok. TikTok. 2022.https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/strengthening-our-policies-to-promote-safety-security-and-wellbeing-on-tiktok (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

- 3Healthcare: Prescription-only medicine. The Advertising Standards Authority Ltd. 2022.https://www.asa.org.uk/advice-online/healthcare-prescription-only-medicine.html (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

- 4Influencer culture: Lights, camera, inaction? House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. 2022.https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/22107/documents/164150/default/ (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

- 5NHS treating record number of young people for eating disorders. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/2022/03/nhs-treating-record-number-of-young-people-for-eating-disorders/ (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

- 6Padín PF, González-Rodríguez R, Verde-Diego C, et al. Social media and eating disorder psychopathology: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology. 2021;15. doi:10.5817/cp2021-3-6

- 7Kolovos B. Shortage of diabetes medication Ozempic after TikTok users promote drug for weight loss. The Guardian. 2022.https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/31/shortage-of-diabetes-medication-ozempic-after-tiktok-users-promote-drug-for-weight-loss (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

- 8Online Safety Bill. UK Parliament. 2022.https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3137 (accessed 7 Sep 2022).

You may also be interested in

More lifestyle support needed for patients starting medicines for cardiovascular disease, study concludes

It’s not just medicines that improve health — pharmacists need a better understanding of nutrition