What if a pharmacy student could put on a virtual reality (VR) headset, walk through a simulated pharmacy environment and chat to patient avatars along the way? Or what if they could sit down at a computer to practise dispensing while accessing mock patient records?

Perhaps they could walk into a perfectly replicated mock ward or GP surgery where they can practise their diagnostic and clinical skills on eerie human-size dummies hooked up to monitors with real-time data?

A few years ago, this may have all seemed like science fiction. However, as schools of pharmacy prepare to relaunch their MPharm courses to meet the General Pharmaceutical Council’s new clinical standards (which include a requirement to make use of the latest digital technologies), they are spending large sums of money on simulation technologies to help get their students ready for the real world[1].

At the University of Birmingham, the School of Pharmacy has been making big changes, many of which will be put in place in the autumn 2023 semester, explains Sarah Pontefract, a lecturer in clinical pharmacy.

You can do everything on there, pick things off shelves, label things and check prescriptions

Sarah Pontefract, lecturer in clinical pharmacy, University of Birmingham

All the in-house dispensing training is now provided through an online simulation program, originally developed at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, called MyDispense (see Figure 1).

“You can do everything on there, pick things off shelves, label things and check prescriptions, and do controlled-drug register entries,” says Pontefract. “It allows students to think about things like the legalities of the label and what the process of dispensing and checking looks like.” The program gives students immediate and tailored feedback on their performance.

The school has also adopted a simulated version of ‘Patient Knows Best’ — a patient facing record used by some NHS trusts [in the UK] — which allows them to set up mock patient cases and “communicate” with the patient electronically.

Pontefract has been trying to integrate dummy electronic patient records into university teaching for years but has faced many barriers, including contracts, worries about data breaches or systems that do not allow students to follow a patient’s treatment journey but instead deal with a one-off interaction.

It is vital for students to have access to all this if they are to become safe prescribers, says Pontefract, not least because the systems used in many real-life placements do not allow for student access, “which can be a real barrier for experiential learning”.

“It is also about understanding the pitfalls of the system. How you get fed up that you keep getting alerts but can’t ignore them and understanding that electronic systems don’t make you a safe prescriber,” she says.

360 videos

Students also find this technology useful when they go out to a clinical setting because they feel less anxious, having practised in a simulated and safe environment, says Atif Saddiq, assistant professor in primary care pharmacy practice and digital lead for the MPharm programme at the University of Bradford.

From the 2023/2024 academic year, Saddiq says students at his university will be able to immerse themselves in new software that it has been developing.

We can really build up a very complex patient scenario and we can tailor it to what we’re studying

Atif Saddiq, digital lead for the MPharm programme, University of Bradford

Saddiq has worked with NHS England’s technology-enhanced learning team to create several 360 video scenes, using a real-life, local GP practice. “It takes the students around a day in the life of a pharmacist in general practice, with a number of different scenes and interactive activities that they can take on,” he explains.

The team has also developed a program that mimics a range of scenarios that pharmacists might come across in general practice. Students are assigned their own patient profile and are provided with a case study to work through. “We can really build up a very complex patient scenario by adding in things like blood test results, blood pressure — all sorts — and we can tailor it to what we’re studying.”

The department has also brought in new simulated dispensing software, which more closely mimics what happens in the real world, as well as a dummy version of PharmOutcomes — commonly used for community clinical services. “We are trying to get our students to a situation where the placements are more meaningful, so they’re not just stood on the side, not really adding any value to the team or to their learning,” he explains.

Generative artificial intelligence

The goal is to provide the students with experiences that they may come across rarely in practice, explains Natalie Lewis, associate head of school and senior teaching fellow at Aston University in Birmingham.

“How can you guarantee that someone will get to see and recognise anaphylaxis?” she asks.

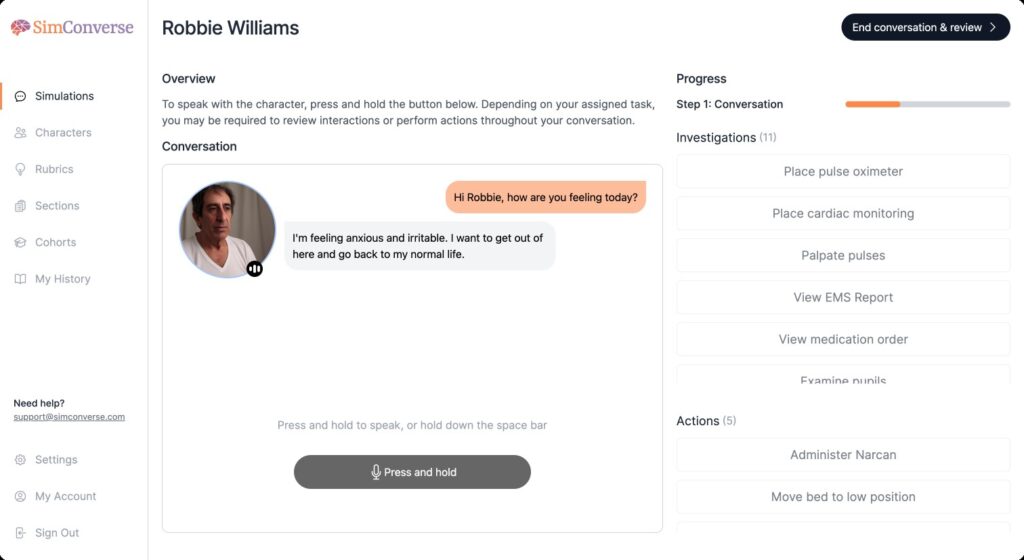

The university’s pharmacy school has put a huge amount of work into making the most of SimConverse, a computer software that teaches communication skills by using generative artificial intelligence (AI) — algorithms that create new content by learning from data they are trained on — to play the role of patients (see Figure 2).

SimConverse

The software, through which students have verbal conversations, prepares students for their placement activity; for example, supervising over-the-counter sales or taking a drug history, Lewis adds.

Although the school bought the software, the patient scenarios have all been programmed in house, in collaboration with community, GP and hospital providers, to ensure consistency, accuracy and relevance.

Students need to hold a consultation and reach shared decisions with their AI patient to optimise their care

Olivia Mina, teaching fellow, Aston Pharmacy School

“We have developed 60 to 70 scenarios using SimConverse,” explains Olivia Mina, teaching fellow within the pharmacy school. One example involves students taking on the role of a GP pharmacist holding a hypertension clinic: a patient booked into the clinic has high blood pressure readings and has been struggling to maintain a healthy diet recently with the rising cost of living.

“Students need to hold a consultation and reach shared decisions with their AI patient to optimise their care,” she explains. The software enables teaching staff to track what their students have done and how well they managed the interactions.

Virtual reality

In addition to these desktop programs, there are increasingly sophisticated VR systems on the market, but these are yet to be widely adopted within pharmacy education.

The University of Birmingham looked into this highly immersive VR when it built its new clinical skills suite for healthcare students, but found that the technology is not quite ready, explains Pontefract, adding that it will reassess in the future. “But if you’re spending hundreds of thousands of pounds, you need the technology to be worthwhile and used regularly.”

A lot of the commercially-available simulation products are extremely expensive

Katie Maddock, head of the School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering, Keele University

Katie Maddock, head of the School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering at Keele University, agrees that cost and sustainability of this fast-moving technology is one of the biggest barriers to it being adopted.

She has a team that specialises in virtual and augmented reality. “A lot of the commercially-available simulation products are extremely expensive so demonstrating value for money is very difficult,” she points out.

However, she adds that simple technology can be very effective. Keele has developed a shared-decision-making avatar with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, known as the ‘Keele Virtual Patient’, and uses a simplified version of it to teach communication skills in the first year of the MPharm.

Jonathan Berry, an academic clinical educator within the School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering, also developed a ‘Tamagotchi’ type avatar called Bertie, a version of which will be used for pharmacy students in their fourth year at Keele (see Box 1).

Box 1: Tamagotchi care

Originally developed at Keele University to test students’ ability to care for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ‘Bertie’ is an avatar you have to keep alive for 72 hours, with a medical student, a nursing student and a pharmacy student working together.

The postgraduate nursing team at Swansea University has since adapted this software to look after three patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, who are admitted to hospital for different reasons. The exercise is all done on a mobile phone. Students can order tests and see results, and ask the patients questions, and are expected to record what they have done in the notes in the software.

Keele is now planning to adopt the Swansea approach for fourth-year pharmacy students, explains Katie Maddock, head of the School Pharmacy and Bioengineering at Keele University. “Students always really enjoy the Tamagotchi avatars. You get them posting that their patient has sat up for the first time and he’s going to have chips for his dinner. They get invested and that’s what we want.”

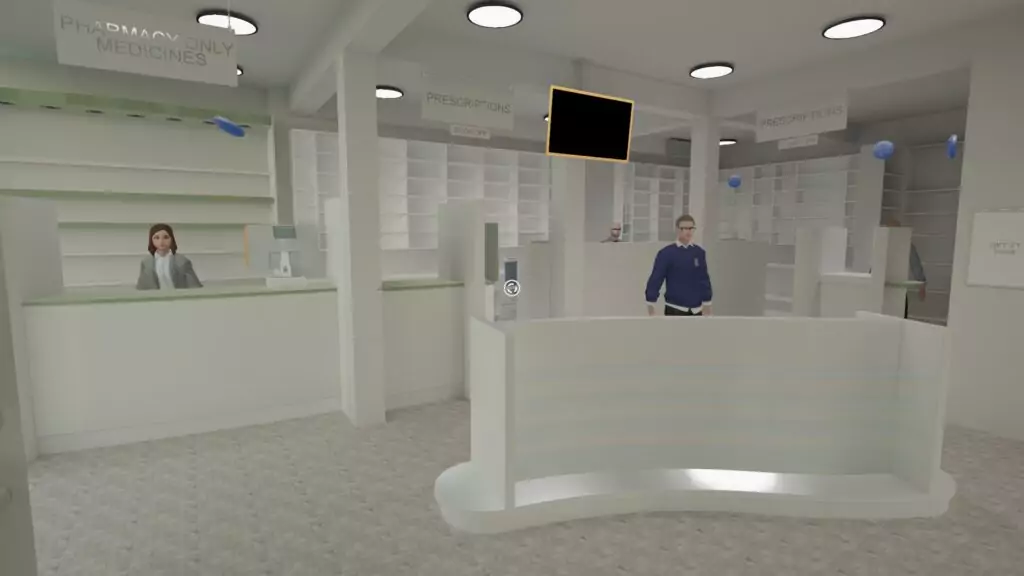

At the School of Pharmacy at University College London, students are wearing basic VR headsets to interact with patients in community pharmacies and GP practices, using software developed in-house (see Box 2 and Figure 3). The software can also be used without a VR headset by moving around an image on a computer screen.

Box 2: Virtual reality avatars

Stephen Hilton, associate professor in the School of Pharmacy at University College London (UCL), first developed a virtual reality (VR) “digital twin” version of his laboratory during the COVID-19 pandemic. Users can interact with everything — pick things up, write on noticeboards and watch presentations, as well as chat to avatars. It changed the way researchers were able to work and collaborate, he notes.

University College London

Researchers have now done the same for other settings, such as a pharmacy and a GP practice, which students can access either using £200 VR headsets or on a PC desktop. Ayah Al-Dargazelli, a pharmacist and PhD researcher at UCL, is working on an advanced version of the technology and has created artificial intelligence avatars for the university’s Greenlight Virtual Pharmacy, which replicate patients asking about minor ailments. “When you speak to the avatars and ask them questions, they reply like a real patient; they are almost emotionally intelligent,” she explains.

This year, working with Imperial College London, Al-Dargazelli will test whether the technology can be used for an Objective Structured Clinical Examination. “Because it is our software, we can update it almost instantaneously. I can literally type in a scenario, it’s just incredible. It is a real hands-on experience.”

Simulated environments

But simulations need to be realistic for students to take them seriously. “If you’re going to use tech in simulation, it has to be realistic enough for the students to forget that they’re using the tech — they’re performing a task,” says Maddock.

Although mock wards and community pharmacies have been used in pharmacy education for years, use of technology has enabled them to become more realistic. Kingston University opened its new hospital and GP surgery simulation units in February 2023 (see Figure 4).

Reem Kayyali, professor of clinical and applied pharmacy practice, and head of pharmacy at Kingston, explains that students can use the units to practise vaccinations; learn how to deal with medical emergencies, with high-fidelity mannequins representing different ethnicities and ages; and use point-of-care testing devices, such as portable electrocardiograms.

The simulation needs to be authentic if I’m going to expect a provider to allow that student to be part of the team

Reem Kayyali, head of pharmacy, Kingston University

Video cameras allow tutors to monitor students from a distance and the computers in the simulated GP practice and community pharmacy are connected to a patient medication record system.

“When we send a student to a placement in a hospital and a GP practice, we need to trust that student to meet that standard. [The simulation] needs to be authentic if I’m going to expect a provider to allow that student to be productive and part of the team,” says Kayyali.

Kingston University

Kingston is also looking into providing a more immersive experience by adding the sounds of a busy ward, for example. From the 2024/2025 academic year, most, if not all, clinical teaching will be done in these settings, she explains.

Maddock believes there is some scope for simulation to replace clinical placements, as long as it is carefully thought through. “Things like simulated wards are a great opportunity because they are a safe learning space for students to do placement-like activities without being on placement,” she adds.

But when it comes to students getting the best out of this technology, pharmacy schools will need to think creatively and “not just dump their students into a simulation”, she adds. The simulation will need to put them under pressure. “It’s got to have a purpose and meet those learning objectives. NHS England won’t pay clinical tariff unless the simulation is replacing actual placement activity.”

Back to basics

At the University of Nottingham, staff are mindful that they need to equip students with the digital skills they will need as practising pharmacists five or ten years from now.

“We’re trying to think about how we use technology in a sophisticated way and not just as a shiny new toy,” says Vibhu Solanki, digital learning lead in the university’s School of Pharmacy.

Digital doesn’t have to be the star of the show, it could just be the enabler

Vibhu Solanki, digital learning lead, School of Pharmacy, University of Nottingham

He explains that Nottingham has scaled back some of its more elaborate technological ideas to consider what is really missing. Pre-COVID-19, the school was playing around with VR and thinking about how AI and augmented reality could supplement its teaching. But often, Solanki says, students need help with some basic IT skills — even using Word — as well as digital communication.

Students already run their own mock community pharmacy in the department. “They have to think about their ability to lead and manage people and processes, and bricks-and-mortar [pharmacies], as well as the NHS systems and private systems, and juggling all those different roles,” he adds.

The school is grappling with how to manage student use of AI. This year, for example, students are being asked to use artificial intelligence-driven chatbot ChatGPT to write a business plan for a community pharmacy.

“But what we are asking them is: what are you going to do with that? How do you fact check it or add to it? We’re training them to ask questions and say: ‘I’m not scared of this tool but I’m suspicious of it in a healthy way’.

“Digital doesn’t have to be the star of the show, it could just be the enabler.”

- 1General Pharmaceutical Council, Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland. Standards for the initial education and training of pharmacists. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2021. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/standards-for-the-initial-education-and-training-of-pharmacists-january-2021_final-v1.3.pdf (accessed 16 October 2023)