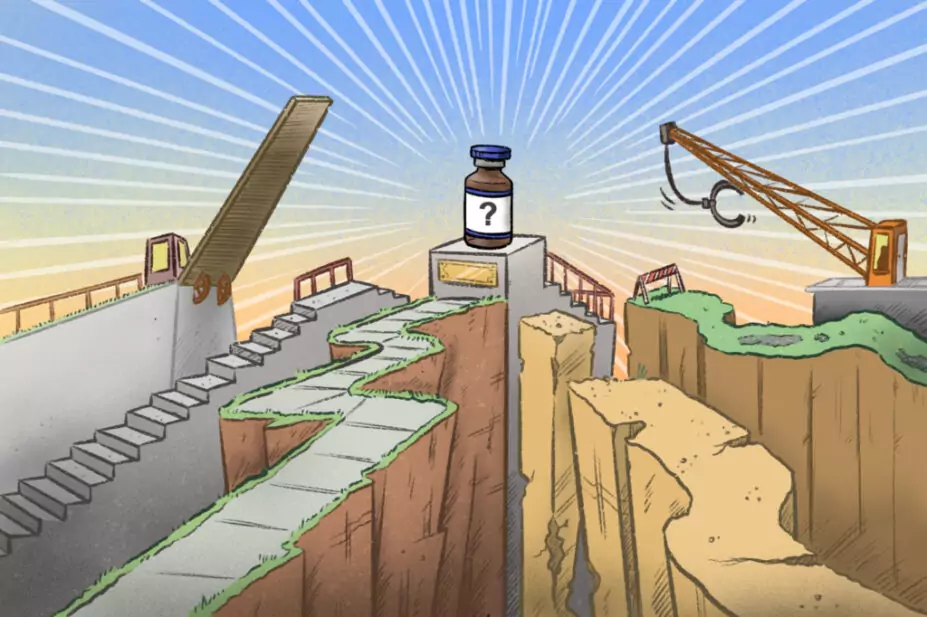

Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

Portia Thorman knows her son would not be alive without having had access to nusinersen (Spinraza; Biogen) to treat his type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

Type 1 is the most severe form of SMA, a genetic condition that develops in infants under the age of six months affecting muscle strength and movement, causing difficulties with eating, breathing and swallowing. According to the latest data published by the government in 2019, the estimated birth prevalence is 6.2 per 100,000 births.

It was not until 2019 that the first of three treatments for the condition were approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and offered on the NHS. Prior to this, NHS guidance says “babies with type 1 [SMA] rarely survived beyond the first few years of life”.

But some babies, including Thorman’s son, were able to access these treatments earlier than 2019 through compassionate use schemes, set up by the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture them.

Compassionate use schemes — which have been used since the 1990s for the early provision of investigational antiretrovirals during the HIV/AIDS crisis — enable prescribers to supply unlicensed medicines to patients with a “seriously debilitating disease or whose disease is considered to be life-threatening, and who cannot be treated satisfactorily by an authorised medicinal product”, in line with the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 in the UK.

The legislation requires the medicine being supplied for compassionate use to be either the subject of an application for a marketing authorisation or undergoing clinical trials.

Compassionate use pathways

In the UK, there are multiple routes through which prescribers can supply patients with medicines for compassionate use (see Box 1), with research suggesting that pharmaceutical company-led expanded access programmes (EAPs) are the most frequently used.

Box 1: Types of compassionate use scheme

There are three different types of compassionate use scheme available in the UK:

- ‘Early access to medicines scheme’ — a two-step evaluation process through which pharmaceutical companies can apply to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to supply unlicensed medicines free of charge to patients with a clinical need that is not met by a medicine already authorised and on the market in the UK. This authorisation lasts for a year and can be renewed by the company.

- ‘Expanded access programmes’ — led by the manufacturer, which offers the medicine prior to clinical approval to a patient or an identified cohort of patients free of charge. The efficacy of the medicine within the cohort can be used by the company as ‘real world data’.

- Consultant-led schemes — initiated by the prescribing clinician for an individual patient. The applications are made directly to the pharmaceutical company or through the MHRA for access to a specific medicine.

In 2016, following clinical trials, Biogen made nusinersen available through a global EAP, giving patients with type 1 SMA access to the treatment before regulatory approval and commercial availability. This was the first treatment for SMA globally, having been approved in the United States in December 2016. The EAP became one of the largest in rare disease history, enrolling 835 patients in 120 centres across 30 countries, according to a paper published on the programme in May 2019.

“My son, now aged six [years] and living with SMA type 1, accessed Spinraza in 2017 via this route,” says Thorman, who is advocacy lead at the charity Spinal Muscular Atrophy UK. The treatment means that Thorman’s son is one of nearly three quarters (73%) of children with type 1 SMA in the UK who have exceeded the age of two years.

Patients treated at an academic or specialist centre, or a centre involved in clinical trials, are more likely to access an unapproved or locally unavailable medicine via compassionate use

Paul Aliu, head of the global governance office in the cross-divisional chief medical office at Novartis

However, not every child with SMA type 1 had the same access. “There was, however, a very slow roll out of this treatment across the UK, which led to inequity of access across the country and, as the UK fell behind other European countries, we saw several families travelling abroad to access treatment,” Thorman explains.

Of 106 responses to freedom of information (FOI) requests sent by The Pharmaceutical Journal to all acute trusts in England, 47 provided data on the number of patients treated through company-led compassionate use schemes. These data indicated that inequity of access through these schemes has become a significant issue.

In its response, Hampshire Hospitals NHS Trust reported the highest number of patients treated through compassionate use and free of charge schemes, at 1,246 patients between April 2014 and April 2023. Meanwhile, two trusts — Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation Trust in West Sussex, and Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust in Lancashire — said they had not treated any patients through these schemes in that time.

This picture is also reflected by pharmaceutical companies. A study carried out by Novartis and published in JAMA in 2022 found that regional availability varies, despite the fact that the UK is among the top ten high-income countries to request medicines for compassionate use.

“Based on our experience and program data over the years, we observe disparity in access to medicines through the compassionate use scheme across many countries, including the UK,” says Paul Aliu, head of the global governance office in the cross-divisional chief medical office at Novartis.

“Patients treated at an academic or specialist centre, or a centre involved in clinical trials, are more likely to access an unapproved or locally unavailable medicine via compassionate use,” he says, adding that Novartis received more than 1,000 such requests from the UK between 2018 and 2020, “largely in oncology and from the type of centres described above”.

“Compassionate use access can also be dependent on the level of awareness of the treating physician, the enabling local regulatory environment, and the ease of the compassionate use process and support available both within and outside of the particular healthcare institution.”

Neither the Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation Trust nor the Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust responded to requests for comment on why patients had not been supplied medicines through compassionate use schemes.

Administrative burden

However, Ezinne Ezeala, lead clinical pharmacist in oncology at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust — which could not provide data on the number of patients it had treated through company-led compassionate use schemes — says that accessing these schemes “becomes a postcode lottery because some clinicians and research centres are very proactive in taking on these schemes”.

“It comes down to resource,” she says, describing some schemes as “paperwork heavy”.

“Each compassionate use scheme will have a different portal… lots of different logins, training every member of staff. From a pharmacy perspective, that’s the challenge; training everybody to know what to do in each compassionate use scheme and this could just be for one patient.”

Ezeala adds that offering medicines through compassionate use schemes also opens trusts up to potential legal risks, such as medical negligence claims. “Some of them, you almost need to get a legal team to have a look at the scheme,” she says. “Does it continue until progression? Does it continue until toxicity? It depends on the wording of it.”

In addition to this uncertainty, working at a district general hospital means that the patients for whom Ezeala can request medicines on compassionate use grounds are few and far between.

“When I was head of chemotherapy, I would be a little wary because we don’t get that many [patients on compassionate use schemes],” she says. “We didn’t have the trained eyes to look at them, we didn’t have the governance structure to review them.”

NHS England guidance on schemes offering medicines free of charge was published on 3 August 2023. The guidance aims “to support the NHS to drive value” from these schemes but also warns that such schemes can “lead to unwarranted variation, undermine NICE guidance and contribute to inequitable access to these medicines across England”, highlighting the need for “appropriate governance and management”, such as developing a local standard operating procedure.

Prior to the guidance’s publication, Ezeala said there was “not much governance” around company-led schemes, so hospital trusts felt “safer with the [early access to medicines scheme] because its gone through the MHRA [Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency] and there’s a bit of assurance around it”.

Compassionate use exists in part because drug design and testing is lengthy and there is excessive cost and bureaucracy in trial management

Taha Lodhi, a clinical fellow in the department of clinical oncology at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester

EAMS is a two-step approval process set up by the MHRA in April 2014 that is aimed to allow access to therapies that have at least completed phase III trials and fulfil an otherwise unmet clinical need. Through the assessment process the MHRA evaluates clinical and non-clinical data and assesses the benefits and risks of the medicine.

While trusts may prefer to treat patients using the EAMS, companies are less likely to offer medicines this way than through their own company-led scheme.

Research from University College London Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, published in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology in 2022, found that 90% of 81 compassionate use schemes reviewed by the trust between 2013 and 2019 were company led, compared with 10% that were accessed through the EAMS.

The authors say the findings support an “apparent pharmaceutical industry preference” to offer schemes outside of the EAMS, with company-led schemes becoming “increasingly common”.

Meanwhile, the researchers note that use of the EAMS “nationally by pharmaceutical manufacturers and availability of treatments by this route has shown no indication of growth” (see Box 2).

Box 2: Medicines supplied through the ‘Early access to medicines scheme’

Pharmaceutical companies applying to offer medicines through ‘Early access to medicines scheme’ (EAMS) must first apply for a ‘promising innovative medicines’ (PIM) designation. This takes into account non-clinical and clinical data available on the product and assesses the medicine against three criteria, including whether the condition it will treat is considered life-threatening or seriously debilitating.

Following a successful PIM designation, the company can then go on to apply for a ‘scientific opinion’. This considers the risks and benefits of the medicine based on clinical and non-clinical data gathered from the patients who will benefit from it. Companies are also required to submit a dossier that includes a treatment protocol, pharmacovigilance requirements and data to be collected on patients being treated.

Data provided by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency to The Pharmaceutical Journal following a freedom of information request shows that companies have made 161 applications to the first stage of the EAMS process since its launch in 2014, of which 124 were successful. However, only 65 applications were made for a scientific opinion, of which 47 medicines were successful and later made available to patients.

A report published by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) in May 2014 says the EAMS is viewed as a “method for evaluating drugs in small populations” but suggests pharmaceutical companies are deterred by the cost of applying for a scientific opinion at £25,643.

The PIM designation, which costs £3,986, “is viewed positively as a relatively inexpensive method of obtaining validation for a therapy”, it says, adding that manufacturers “will review whether it is more cost effective to continue with the usual route to drug approval without applying for the EAMS scientific opinion”.

Applications to EAMS overall have also declined, having peaked in 2018 when 27 applications were made. In 2022, just 14 applications were submitted for a PIM designation.

“Compassionate use exists in part because drug design and testing is lengthy and there is excessive cost and bureaucracy in trial management,” says Taha Lodhi, a clinical fellow in the department of clinical oncology at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust in Manchester.

“Given the cost of drugs and the time it takes to be given NICE guidance and funding, our centre experience shows [these schemes] will become more frequent.”

Achieving equitable access

If supplying medicines through compassionate use looks set to increase and the research suggests pharmaceutical companies will take to making these offerings outside of the EAMS, how can equitable access be ensured?

“One of the barriers to better access is the lack of a centralised compassionate use database,” says Scott Purdon, head of patient advocacy at blood cancer charity Myeloma UK.

“This means that clinicians, who are too pushed for time to navigate the complexities of the system, may not be aware that schemes are available or know how to get patients the drugs that they need.”

Purdon adds that hospital pharmacies are obligated to complete request forms for unlicensed medicines, “so each trust should have a record of all compassionate use medicines prescribed”.

There is no upfront, real-time mechanism nor transparency to accessing compassionate use schemes, which would make the system more impactful, easier to navigate and, ultimately, benefit patients

Scott Purdon, head of patient advocacy at Myeloma UK

But this is not always the case. Out of the 106 responses to The Pharmaceutical Journal’s FOI requests, 55 acute trusts said they could not provide information because they did not hold data centrally on the number of medicines its clinicians had accessed through company-led compassionate use schemes, while 50 trusts said they did not hold centralised data on the number of medicines accessed through EAMS.

“There is no upfront, real-time mechanism nor transparency to accessing compassionate use schemes, which would make the system more impactful, easier to navigate and, ultimately, benefit patients,” says Purdon.

The pharmaceutical industry has said it would also be interested in helping to reduce variation this way. “We support compassionate use schemes to continue access to essential therapies for patients transitioning from clinical trials, and provide early access for patients with high unmet clinical need while licensing and NHS reimbursement arrangements are being finalized,” says Amit Aggarwal, executive director of medical affairs at the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI).

“There is signification variation in the use of such schemes. Industry would welcome working with the NHS to help make sure the processes for communicating, evaluating, and implementing such schemes more efficient and consistent to allow more patients to benefit.”

Better data collection on medicines accessed through compassionate use scheme would also have benefits for pharmaceutical companies looking to license their medicines for wider use on the NHS.

“As these medicines could potentially be life-saving or disease modifying – as observed in many instances – effective oversight at an institutional level and the systematic collection of the efficacy and safety data will help add to the body of knowledge on the medicine, on its use in the ‘real-world’ setting, and further inform clinical practice,” says Aliu.

However, the latest NHS England guidance notes that data collection in this way enables companies to “circumnavigate head-to-head trial processes,” while also “creating an administrative burden and data protection risk for the NHS”.

When asked what plans the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has to address the inequity of access to these medicines, a spokesperson said: “The NHS in England offers routes to support early access to medicines in a timely, safe way, such as the EAMS, the Innovative Licensing and Access Pathway (ILAP) and the Innovative Medicines Fund (IMF).”

Medicines offered through the IMF or ILAP differ from compassionate use schemes in that they are not provided to the NHS free of charge.

The DHSC spokesperson added that prescribers have the prerogative to resort to unlicensed medicines when there is no licensed medicine capable of meeting the clinical needs of individual patients but said that their use is the responsibility of prescribers responsible for the care of individual patients.

While the government may not have plans to ease the legal, administrative or time burdens on a national scale for smaller hospital teams accessing compassionate use medicines, Lodhi says it is still “morally right to offer such drugs to patients who will not be alive when guidance and funding are green lit”.

“Right now, there are too many barriers to access and huge geographical variations across the country,” adds Purdon. “This is unacceptable.”

- This article was corrected on 2 October 2023 after it was noted that data from Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust included patients treated with both unlicensed and NICE-approved medicines. This article was amended on 18 August 2023 to clarify that some company-led compassionate use schemes are out of the scope of NHS England guidance

3 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Very interesting article. Thank you PJ

I supplied the data in response to the FOIA inquiry on behalf of Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust. In reply to the question "How many requests has your trust made to pharmaceutical companies for access to medicines offered through a company-led compassionate use of free of charge scheme each year between April 2014 and April 2023" we replied that we did not hold the data but in order to try and be helpful with the answer to the next question, "How many patients have received treatment with unlicensed medicines obtained this way each year between April 2014 and April 2023" I added the caveat "these are the number of patients who have received FOC, discounted, or compassionate-use medicines during the year regardless of their licensed status" as we could not distinguish between schemes put in place before licensing or after NICE approval.

This caveat has been completely ignored by the author of this article and it is disappointing to see the data misused in this way.

Dear Christopher,

Thank you for highlighting the caveat on the data from Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust. The article has now been updated to reflect this. If you have any further queries on the data please get in touch: carolyn.wickware@rpharms.com

Kind regards,

Carolyn Wickware

Executive editor