Mclean/Shutterstock

It should have been a cause for celebration: the first-in-class, disease-modifying drug that reaches beyond alternative symptomatic treatments to target an underlying cause of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) directly.

However, the approval of aducanumab (Aduhelm; Biogen) in June 2021 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has instead resulted in resignations, division and claims of favourable treatment by staff at the US drug regulator. Aducanumab has yet to be given the green light in the UK, so whether it will provoke the same controversy on this side of the Atlantic remains to be seen (see Box).

Either way, the monoclonal antibody has sparked a debate on the way that surrogate endpoints and post-hoc analyses are used in trials and the fast-track approvals increasingly offered by drug regulators around the world.

I hope that this is a one in a million event, and that we don’t see this type of regulatory failure again

Caleb Alexander, member of the expert advisory committee consulted by the FDA on aducanumab’s efficacy

“I hope that this is a one in a million event, and that we don’t see this type of regulatory failure again”, is how Caleb Alexander, a member of the expert advisory committee consulted by the FDA on aducanumab’s efficacy, puts it. At 11 votes to none, the committee members agreed — the evidence for efficacy was not there[1,2].

“I should point out,” Alexander continues, “the FDA are not bound to follow the committee’s recommendations — although, in about 80% of cases they do. What is unusual here is that, typically, in the 20% of cases where the FDA may not follow the committee’s recommendations, it’s in settings where there’s a split decision”. The subsequent decision to approve led to the resignation of three committee members, discontent with the FDA’s handling of the situation[3].

As well as diverging from the expert opinion, the FDA also suggested switching aducanumab’s application from a standard Biologics License Application (BLA) to the Accelerated Approval (AA) programme, which requires a different assessment of evidence, and one that the committee was told not to consider in its evaluation.

More commonly used for the approval of new cancer drugs, this pathway is intended for “earlier approval of drugs that treat serious conditions, and that fill an unmet medical need, based on a surrogate endpoint”[4]. Under the AA programme, Biogen will have to prove actual clinical benefit in a post-market study set to run until 2030.

AD, like cancer, is both a serious condition — affecting more than 885,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide — and one lacking a pharmaceutical solution. Currently, cholinesterase inhibitors or the partial N-methyl D-aspartate antagonist memantine are licensed for AD and dementia in the UK, improving symptoms but not tackling disease causes[5,6]. However, it is the use of the surrogate endpoint in aducanumab’s trial that has caused grumblings in the scientific community.

Box: UK approval

In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has an approval mechanism similar to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Accelerated Approval programme for serious conditions that have a significant public health need — the Innovative Licensing and Access Pathway (ILAP)[7]. And Alzheimer’s Research UK has written to the health secretary, requesting governmental aid in getting aducanumab evaluated as quickly as possible, to obtain answers for its community. When contacted by The Pharmaceutical Journal, the MHRA said that it could not comment on future or ongoing applications.

Then, there is the substantial hurdle of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approval to pass for NHS prescribing. The United States’s Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which — similar to the UK’s NICE — provides cost-effectiveness analyses of new drugs, released a draft report that established a cost-effective annual price as between US$2,560—8,290 (£1,840–5,959) — a far cry from Biogen’s marketed cost of US$56,000 (£42,253)[8].

“I think that the UK and other countries have a major opportunity to get this right, and not repeat the same mistakes the FDA has made,” says Caleb Alexander, a member of the expert advisory committee consulted by the FDA on aducanumab’s efficacy.

Amyloid-beta cascade hypothesis

Surrogate endpoints can be anything “reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit”, whether a blood or urine biomarker, or a radiological image to measure things such as tumour size[9]. Aducanumab’s sponsors, US-based Biogen and the Japanese Eisai, presented the brain protein amyloid as the surrogate biomarker predicting clinical benefit in AD — but there is not a scientific consensus on amyloid’s role in AD pathology.

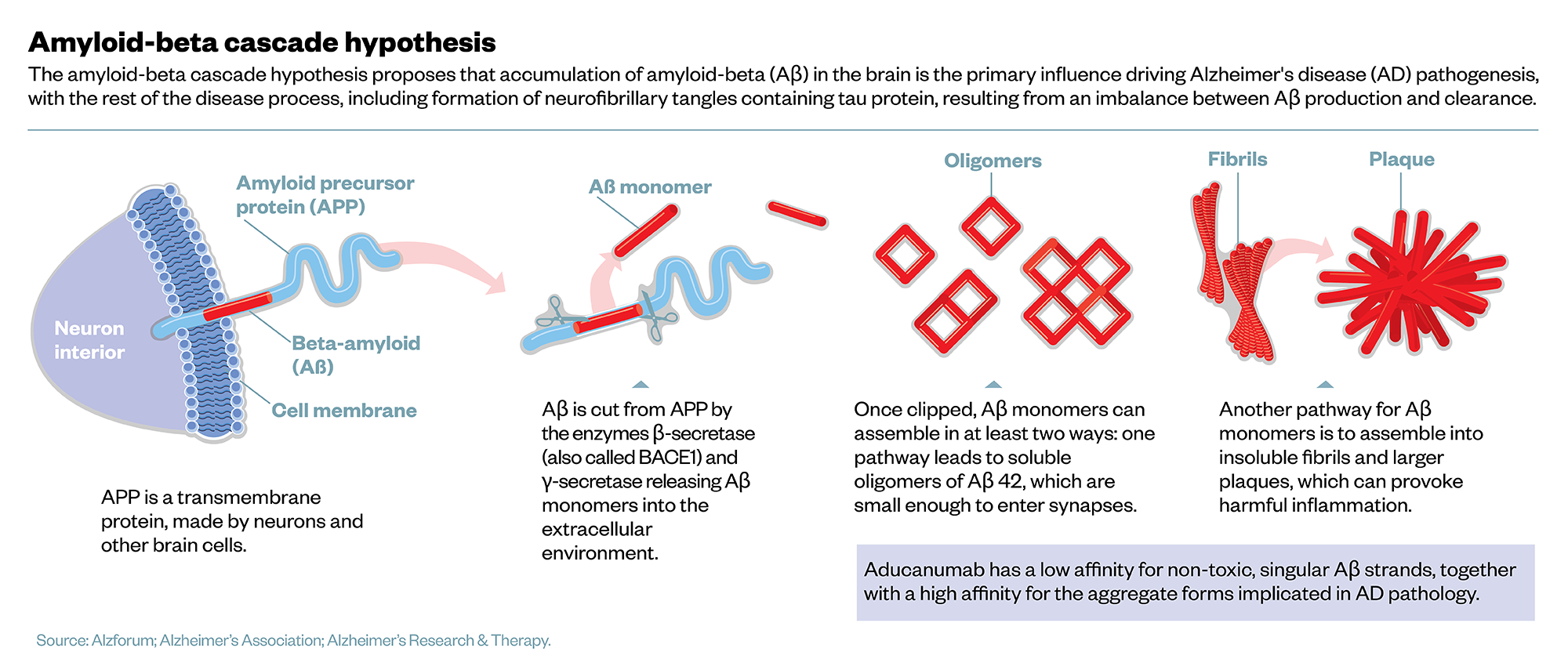

It comes down to whether the amyloid-beta cascade hypothesis, proposed by neuroscientists John Hardy and Gerald Higgins in 1992, is still the best model for explaining the causes of AD[10,11]. In this hypothesis, a protein in the brain — the amyloid precursor protein (APP) — is enzymatically cleaved into smaller proteins of varying length, known as amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides (see Figure).

“This processing of APP does happen normally — young people produce amyloid-beta, but then it is kept in solution,” Henrick Zetterberg, professor of neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and the UK Dementia Research Institute at University College London (UCL), explains. The danger comes in longer forms of Aβ, which are sticky and clump together in ‘aggregates’ that precipitate out of solution.

“The onset of the disease is when amyloid-beta starts to aggregate. When this process has started, it is like a template for the misfolding cascade, so it takes off, and then it seems to spread over the brain.” Eventually, as the amyloid aggregates harden into plaques, nearby neurons react by pruning back synapses, causing neuronal death.

But there remain stages in the amyloid-beta cascade that are not fully understood. For instance, how plaque build-up triggers the neuron’s pruning mechanism is unclear. Robert Howard, professor of old age psychiatry at UCL, says of the uncertainty: “It’s completely possible that amyloid plaques in AD are basically just tombstones for the remains of dead neurons, rather than being a key process that is driving the disease. We honestly just don’t know.”

Even proponents of the hypothesis must confront the disappointing performance amyloid monoclonal antibodies have had in clinical trials to date. “There was quite a powerful meta-analysis in the BMJ recently,” continues Howard, who is outspoken against aducanumab’s approval, “and if we look at the pooled effect of amyloid lowering on cognitive function, it’s absolutely negligible.” The study analysed data from 14 trials and 4 amyloid antibodies, including aducanumab, and concluded that “reduction in amyloid levels alone is unlikely to substantially slow cognitive decline”, even suggesting anti-amyloid drugs are not a viable treatment strategy[12].

Evidence for aducanumab

Biogen argues its antibody is different. A 2018 study, run by Biogen scientists, compared molecular mechanisms of several amyloid antibodies, and determined that aducanumab had the better combination of low affinity for non-toxic, singular Aβ strands, together with high affinity for aggregate forms, making it the most selective in binding to the correct target[13]. Biogen’s head of research and development Alfred Sandrock emphasised in a statement that this meant “there is no basis for using the failure of [other] antibodies as a reason to question the approval of Aduhelm”[14].

If there was a convincing signal on measures of clinical efficacy, it would have jumped out from the trials

Robert Howard, professor of old age psychiatry at University College London

“There’s no doubt that aducanumab is able to reduce the amyloid levels in the brain,” Howard acknowledges. “But if there was a convincing signal on measures of clinical efficacy, it would have jumped out from the trials.”

He refers to the two large-scale phase III clinical trials, ENGAGE and EMERGE, at the centre of the approval — and the controversy. Testing monthly IV infusions of aducanumab for 18 months, in more than 3,000 patients aged 70 years and over displaying mild cognitive impairment of early AD, there was nothing especially unorthodox about the trial designs. As the chief investigator for Biogen’s ENGAGE trial, Craig Ritchie, professor of psychiatry of ageing at the University of Edinburgh and director of Brain Health Scotland, notes: “They were very typical randomised controlled trials, with a normal range of outcome measures we’ve been using going back 20 or 30 years.

“The interesting thing is that the trials were originally stopped for what is called a futility analysis,” Ritchie explains. This is a pre-specified interim analysis built into the trial design to examine results for inefficacy and save resources. At interim analysis, only EMERGE looked to be meeting primary outcomes. With positive results needed in both trials to be a demonstration of efficacy, Biogen pronounced both trials unsuccessful and began routine post-hoc analysis to identify improvements for the future[15,16].

Post-hoc analysis, however, was complicated by a change of protocol part-way through the trials. To reduce their risk of side effects, patients at increased genetic risk of amyloid build-up were titrated to aducanumab concentrations of 6mg/kg, with higher 10mg/kg doses for low-risk patients[15]. As it became clear that side effects were well-managed, all patients were moved to 10mg/kg, but the timing of the futility break was unchanged. At post-hoc analysis of higher dose patients, they found a positive trend. “The company’s main argument appears to be that, had they had more people on the higher dose for a longer period of time, they would have been able to show, across the whole project, a clinical benefit,” explains Ritchie.

Post-hoc analyses are more prone to bias and generally considered by the scientific community as an unreliable way to draw conclusions. The statistical review by the FDA highlighted concerns about the robustness of the post-hoc analysis, critiquing the dismissal of the negative ENGAGE study and the subsequent emphasis placed on the one statistically significant timepoint in EMERGE[17–19]. The review concluded that “the totality of the data does not seem to support the efficacy of the high dose”[17].

Commercial implications

With both expert scientific and statistical advice recommending against approval, some have pointed to alleged off-the-books meetings between the FDA and sponsor Biogen, suggesting their dealings went beyond usual sponsor-regulator collaboration[20]. However, Biogen contends that it is common for industry leaders and FDA officials to interact at scientific conferences. A spokesperson for Biogen told The Pharmaceutical Journal: “Discussions of science and drug development happen frequently between industry and regulators, such as the FDA, with the full understanding that no official decisions will result from any such informal communications.”

In the United States, three major clinics have confirmed they will not administer aducanumab until the questions around its efficacy and approval processes are resolved[21]. And with Biogen setting the price point — announced after approval — at US$56,000 (£42,253) per year, it is unclear whether Medicare, the main US health insurance programme for those aged over 65 years, will be able to justify costs[22].

It’s lowered the bar substantially for companies

Craig Ritchie, professor of psychiatry of ageing at the University of Edinburgh

Such commercial implications of aducanumab’s approval cannot be ignored. As Ritchie outlines: “It’s lowered the bar substantially for companies — show reductions in the biomarker amyloid, show some degree of cognitive benefit but not necessarily in line with a study’s priori analysis plan, and you’ll get an accelerated approval.” Within weeks, it had Eli Lilly and Company filing for accelerated approval with early results from only a 257 patient-strong trial of its own amyloid antibody donanemab[23]. Although Eli Lilly has since withdrawn the application after “FDA feedback” indicated approval would be unlikely, it remains an attractive fast-track option to market[24].

Translating into practice

Translating from trials to real-world application is another complication the neurology field faces. An expert panel of AD clinicians pulled together appropriate use recommendations for aducanumab in July 2021 to aid prescribers, noting the need for “substantial infrastructure” changes to support this new management pathway[25]. Much is time-, labour- or cost-intensive; and these clunky or costly areas are those where advances are anticipated next[26].

For instance, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) brain scans are used to monitor reductions of amyloid levels. However, as Zetterberg asks: “How on Earth should I do that as a clinician, if I work in a village, and I am not in London or Boston?” But innovation is happening rapidly in the biomarker space, seeking simpler and cheaper options. “This will open up for usage cerebrospinal (CSF) biomarkers; these are up and running around the globe. It is a bit too early for blood tests — there is a test for detecting amyloid levels in blood, but it detects only small changes compared to CSF,” Zetterberg adds of current efforts. Instead, other biomarkers show more promise: “The plasma phospho-tau test, I think, will be fundamental to how you will examine patients. When you have amyloid on the brain, the neuron responds to that by phosphorylating and secreting the protein tau, and that is measurable in CSF, but also in plasma.”

I think everybody realises that aducanumab and other amyloid drugs are not going to be magic bullets

John Hardy, chair of molecular biology of neurological disease at the UCL Institute of Neurology

Tau, along with the brain’s microglial cells, is associated with neuronal pruning and death following amyloid build-up. Together, they are “the other two drug targets people are interested in now”, John Hardy, chair of molecular biology of neurological disease at the UCL Institute of Neurology, says. Increasingly, scientific consensus is leaning towards all three playing a role in AD progression. “I think everybody realises now that aducanumab and other amyloid drugs are not going to be magic bullets,” Hardy speculates. “We’re going to eventually be going to polypharmacy, where we possibly have an anti-amyloid drug, an anti-tau drug and some sort of microglial drug.”

And the future for AD management will not stop at pharmaceutical solutions. “There’s more and more research going into identifying people who are at risk of disease,” Hardy adds. The link between AD and genetic factors is widely known, but Hardy points to a startling 2020 study that revealed the incidence of AD in North America and Europe decreased 13% per decade over the past 25 years[27].

“That drop”, Hardy points out, “can’t be something genetic — that must be to do with our lifestyle. And so that’s really given impetus to the idea that there are contributing lifestyle factors.” So, there is the potential that aducanumab could prove to be one stepping stone of many towards a comprehensive AD management package.

For now, with just aducanumab and its uncertainties, clinicians in the United States face the all-important question: should they recommend it to patients?

- 1Alexander GC, Emerson S, Kesselheim AS. Evaluation of Aducanumab for Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 2021;325:1717. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.3854

- 2Update on FDA Advisory Committee’s Meeting on Aducanumab in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biogen. 2020.https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/update-fda-advisory-committees-meeting-aducanumab-alzheimers (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 3Mahase E. Three FDA advisory panel members resign over approval of Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ 2021;:n1503. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1503

- 4Accelerated Approval Program. FDA. 2020.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/information-health-care-professionals-drugs/accelerated-approval-program (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 5Wittenberg R, Barraza-Araiza L, Rehill A. Projections of older people with dementia and costs of dementia care in the United Kingdom, 2019–2040. Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science 2019. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/cpec_report_november_2019.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 6Dementia: Key facts. World Health Organisation. 2020.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 7Innovative Licensing and Access Pathway. Gov.uk. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/innovative-licensing-and-access-pathway (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 8Lin G, Whittington M, Synnott P, et al. Aducanumab for Alzheimer’s Disease: Effectiveness and Value. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review 2021. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_ALZ_Draft_Evidence_Report_050521.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 9Development & Approval Process. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2019.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 10Hardy J, Higgins G. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 1992;256:184–5. doi:10.1126/science.1566067

- 11Ricciarelli R, Fedele E. The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease: It’s Time to Change Our Mind. CN 2017;15. doi:10.2174/1570159×15666170116143743

- 12Ackley SF, Zimmerman SC, Brenowitz WD, et al. Effect of reductions in amyloid levels on cognitive change in randomized trials: instrumental variable meta-analysis. BMJ 2021;:n156. doi:10.1136/bmj.n156

- 13Arndt JW, Qian F, Smith BA, et al. Structural and kinetic basis for the selectivity of aducanumab for aggregated forms of amyloid-β. Sci Rep 2018;8. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24501-0

- 14Sandrock A. An open letter to the Alzheimer’s disease community from our Head of Research and Development. Biogen. 2021.https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/open-letter-alzheimers-disease-community-our-head-research-and (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 15Knopman DS, Jones DT, Greicius MD. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2020;17:696–701. doi:10.1002/alz.12213

- 16Kuller LH, Lopez OL. ENGAGE and EMERGE: Truth and consequences? Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2021;17:692–5. doi:10.1002/alz.12286

- 17Peripheral and Central Nervous System (PCNS) Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, November 6, 2020. Combined FDA and Applicant PCNS Drugs Advisory Committee Briefing Document: Statistical Review and Evaluation. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020.https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 18FDA Pre-Recorded Presentation Transcripts for the November 6, 2020 Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee: Title BLA 761178 Statistical Review Aducanumab in Alzheimer’s. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020.https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 19Pre-Recorded Presentation Slides for the November 6, 2020 Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee November 6, 2020: Title BLA 761178 Statistical Review Aducanumab in Alzheimer’s. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020.https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 20Dyer O. FDA calls for investigation into industry influence during Alzheimer’s drug approval. BMJ 2021;:n1778. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1778

- 21Cleveland Clinic, Mount Sinai, and Providence to Not Give Biogen’s New Alzheimer’s Drug. FR24 News. 2021.https://www.fr24news.com/a/2021/07/cleveland-clinic-mount-sinai-and-providence-to-not-give-biogens-new-alzheimers-drug.htm (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 22Biogen and Eisai launch multiple initiatives to help patients with Alzheimer’s disease access ADUHELM. Biogen. 2021.https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-and-eisai-launch-multiple-initiatives-help-patients (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 23Buntz B. Lilly’s push for accelerated FDA approval of Alzheimer’s drug donanemab . Drug Discovery and Development. 2021.https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/lilly-pushing-for-accelerated-fda-approval-of-alzheimers-drug-donanemab/ (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 24Gardner J. Lilly, citing FDA feedback, won’t seek speedy approval of Alzheimer’s drug. Biopharm Dive. 2021.https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/lilly-donanemab-fda-accelerated-review-alzheimers/599118/ (accessed 7 Sep 2021).

- 25Cummings J, Aisen P, Apostolova LG, et al. Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations. J Prev Alz Dis 2021;:1–13. doi:10.14283/jpad.2021.41

- 26Selkoe DJ. Treatments for Alzheimer’s disease emerge. Science 2021;373:624–6. doi:10.1126/science.abi6401

- 27Wolters FJ, Chibnik LB, Waziry R, et al. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States. Neurology 2020;95:e519–31. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000010022