Shutterstock.com

Coronary heart disease (also known as ischaemic heart disease) is a leading cause of death globally[1]

. Furthermore, heart and circulatory diseases caused more than a quarter (27%) of all deaths in the UK in 2018[2]

. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a term that encompasses a range of coronary artery diseases from acute myocardial ischaemia to myocardial infarction (MI), depending on the degree and location of the obstruction. MI is at the more serious end of the spectrum and occurs when the supply of blood to the heart is suddenly stopped, causing myocardial cell death; the condition is estimated to cause a hospital admission every five minutes in the UK

[2]. However, innovations around treatment and prevention of MI have helped improve survival rates: 30-day mortality rates after admission to hospital for acute MI decreased from 12.1 per 100 patients to 8.8 per 100 patients, between 2008 and 2015 in the UK[3]

.

Pharmacists should advise patients and physicians about medicines optimisation, both during hospital admission and in the transition from secondary care to primary care after hospital discharge. This can be as part of the cardiac rehabilitation programme or ongoing medication reviews. Reviews should cover topics including dose optimisation, patient education (to increase adherence to treatment regimens) and suggesting alternative treatments (for patients experiencing adverse effects).

Pathophysiology

Coronary artery disease is most commonly caused by a build-up of atheroma (i.e. fatty substances also known as plaques) in the walls of the coronary arteries[4]

. The disease begins through damage to the vessel wall, often caused by smoking or hypertension. This damage leads to infiltration of cholesterol into the vessel wall, which in turn causes inflammation and subsequent infiltration of white blood cells, forming an atheroma. This causes narrowing of the coronary artery, which can progress to a point where the amount of blood that can flow through is restricted. It is this narrowing that causes ACS. At this stage, the limited blood flow may cause angina (i.e. chest pain that stops within minutes of resting); however, if the overlying plaque suddenly ruptures, it can lead to platelet aggregation, thrombin-induced conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and the formation of a fibrin mesh that traps platelets and results in a thrombus (i.e. a blood clot). If blood flow is completely blocked then myocardial cell death will occur.

Risk factors

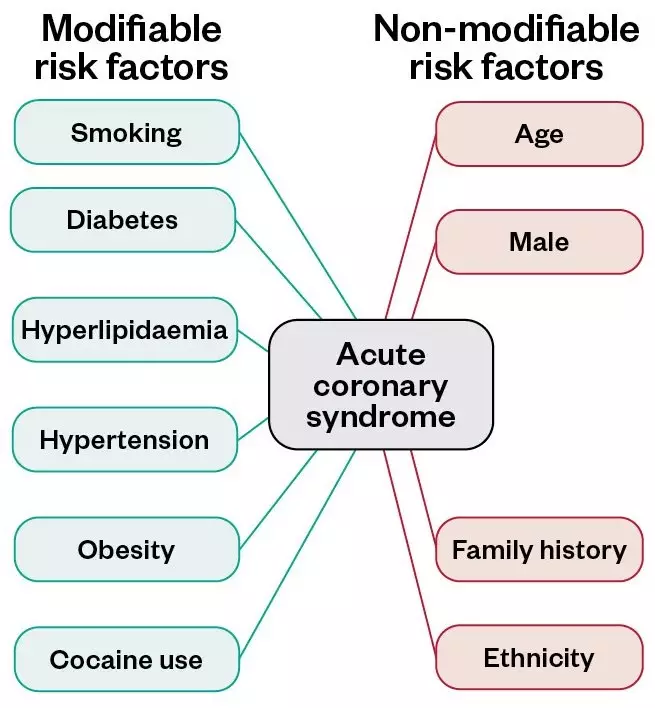

There are several risk factors that increase the chance of a patient developing ACS, which can be divided into modifiable and non-modifiable risks (see Figure 1). Of the modifiable risk factors; hypertension, smoking, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia are most common, with illicit drug use (e.g. cocaine, which can cause coronary artery spasm) being a less common cause[5]

.

Figure 1: Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for acute coronary syndrome

Source: Mclean

Symptoms

The classic symptom of MI is central chest pain that is not relieved by rest. Typically, the pain is described as ‘crushing’ or as a ‘heavy’ sensation, and may radiate to other parts of the body (e.g. the left arm, jaw or back). There may be associated sweating, nausea and/or vomiting, or breathlessness[6]

. However, in some people there are atypical symptoms or no symptoms at all, which is known as ‘silent MI’. Owing to changes in pain perception, this may be more common in older people or those with diabetes[7]

.

At the point when the heart is unable to pump blood around the body, the patient will have a cardiac arrest and will require resuscitation.

Diagnosis

This is made by taking a clinical history and performing an examination, an electrocardiogram (ECG) and blood tests (high cardiac troponin levels in the blood can indicate myocardial damage)[6],[8]

.

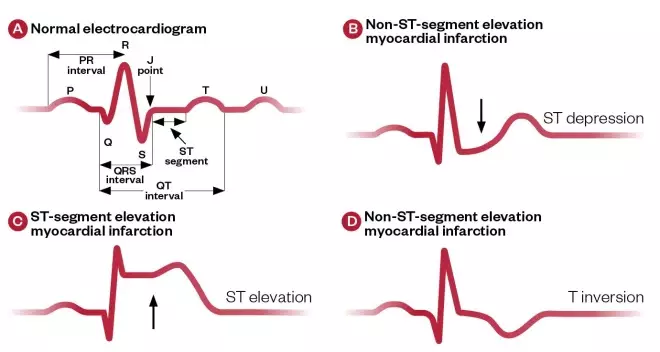

Based on the presence or absence of ST-segment elevation (see Figure 2), an ECG can help to determine what type of ACS has occurred. ACS is divided into three main clinical categories:

- ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) — there is usually complete blockage of a coronary artery, which leads to extensive damage to a large area of the heart. This is suspected when there is ST-segment elevation in two or more anatomically contiguous ECG leads;

- Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) — supply of blood to the heart is only partially blocked, so a smaller section of the heart is damaged. Without treatment it can progress to STEMI;

- Unstable angina — blood supply to the heart is restricted, but there is no permanent damage to the heart muscle. The ECG may be normal and troponin levels will not be raised[9],[10]

.

Figure 2: Typical electrocardiogram changes associated with acute coronary syndrome

Source: Mclean

A) Normal electrocardiogram reading; B) Electrocardiogram reading in a patient with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; C) Electrocardiogram reading in a patient with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; D) Electrocardiogram reading in a patient with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with T inversion.

An ECG is critical in aiding diagnosis because it will help differentiate between STEMI and NSTEMI/unstable angina (see Figure 2)[9]

. However, for an accurate diagnosis, it is essential that the ECG and troponin levels are interpreted alongside clinical history (i.e. increased troponin levels may be owing to renal failure, pulmonary embolism and sepsis).

Universal definition of myocardial infarction

When diagnosing MI, the universal definition should be used[11]

. This definition was updated in 2018 to state: the term ‘acute MI’ should be used when there is acute myocardial injury with evidence of acute myocardial ischaemia and detection of a rise of the cardiac troponin levels with at least one value above the 99th percentile and at least one of the following:

- Symptoms of myocardial ischaemia;

- New ischaemic ECG changes;

- Development of pathological Q waves on the ECG;

- Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormalities in a pattern consistent with ischaemic aetiology;

- Identification of coronary thrombus by angiography or autopsy[11]

.

Management

Pre-hospital setting

If a patient presents with symptoms that indicate MI in a pre-hospital setting, call 999. While waiting for the ambulance, a single dose of aspirin 300mg can be given in the absence of contraindications.[8]

. The patient should be advised to chew the aspirin before swallowing as this gives the most rapid systemic delivery of the drug.

Pain relief (e.g. sublingual glyceryl trinitrate) should be offered as soon as possible and should be given while the patient is sitting. If further pain relief is required, paramedics or hospital staff will administer morphine or diamorphine,[8]

. An anti-emetic, such as metoclopramide, is commonly given with these opioids to prevent nausea from the treatment[12]

.

Hospital setting

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

To treat STEMI successfully, blood flow through the blocked coronary artery must be restored as quickly as possible (either by primary percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or thrombolysis)[8],[9]

. The sooner PCI can be provided following the onset of symptoms of MI, the greater the potential benefit. Therefore, the aim is for ambulance services and primary angioplasty centres to have a coordinated approach to minimise delays in treatment[13]

. To ensure that hospitals with a primary angioplasty service are providing a high-quality service, all centres must submit their data to the national dataset coordinated by the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, which reports these data annually[14]

.

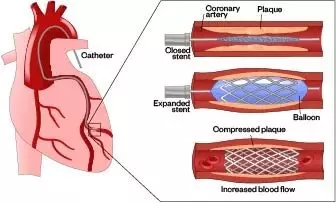

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention

Coronary angiography is performed to assess if the patient is eligible for PCI. This involves injecting a contrast agent through a catheter that is fed through the blood vessels to the heart and coronary arteries. X-rays are then taken to show where there is a narrowing or blockage to blood flow. Once the blockage is located, a balloon catheter is guided to the blockage and inflated to open it[15]

. After inflation, a stent is deployed to maintain the openness of the vessel (See Figure 3)[16]

.

Figure 3: Placement of a stent in the coronary artery restoring blood flow

Source: Shutterstock.com

Prior to PCI, patients receive medication to reduce platelet aggregation and thrombosis. This is usually aspirin and a second antiplatelet agent (ticagrelor, prasugrel or clopidogrel), as well as an anticoagulant (heparin)[9],[17],[18],[19]

. In cases where there is significant thrombus burden, or if on re-opening the vessel there is suboptimal blood flow, the addition of an infusion of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist (tirofiban, abciximab or eptifibatide) may be considered. However, these drugs are potent antiplatelet agents meaning there is an associated risk of bleeding that needs to be taken into account when deciding to use them[9]

.

Thrombolysis

This used to be the first-line treatment for STEMI; however, it is now rarely given and is generally only considered if timely, primary PCI cannot be performed after STEMI diagnosis[9]

. Available thrombolytic drugs are alteplase, reteplase, streptokinase and tenecteplase[20]

.

Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends stratifying the need for coronary intervention against patient risk by using an established risk scoring system, such as the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events score[21]

. Risk scores are based on patient parameters, including age, creatinine levels, Killip class (a scoring system for severity of heart failure based on examination findings) and presence of raised cardiac markers to estimate the probability of 6-month mortality. Patients who are low-risk may be managed without invasive intervention in the first instance, whereas patients who are moderate- or high-risk (i.e. >3% 6-month mortality) should be offered angiography within 72 hours of admission, with follow-on PCI if indicated. For 2017–2019, NHS England and NHS Improvement introduced a best practice tariff to increase the performance of hospitals against this standard[22]

. However, with the widespread use of high-sensitivity troponin, these scores are now less widely used in practice[10]

.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and ticagrelor (or clopidogrel) should be started on admission to hospital, in combination with fondaparinux, a factor Xa inhibitor, which is given by subcutaneous injection while the patient awaits PCI[10]

. Owing to the increased risk of bleeding if prasugrel is used, this should only be commenced at the time of PCI[23]

.

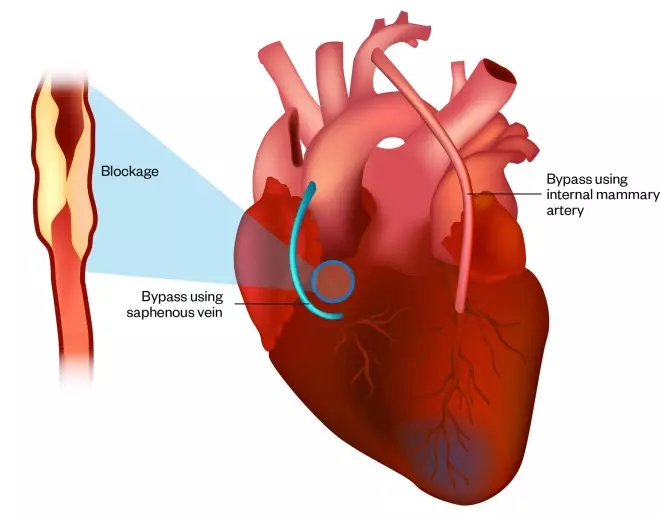

Coronary artery bypass graft

A small number of patients with ACS may be referred for an urgent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) in preference to PCI[9],[10]

. This is generally reserved for patients who have multi-vessel disease; disease of the left main stem artery; or where surgery is considered to offer a better revascularisation option for the patient. CABG is a more invasive procedure requiring division of the sternum (sternotomy) and traditional ‘open heart surgery’. Blood vessels from another part of the body are used – commonly the saphenous vein found in the leg or the internal mammary artery found in the chest wall – to bypass the diseased part of the coronary arteries (see Figure 4)[24]

.

Figure 4: Coronary artery bypass surgery using saphenous vein and internal mammary artery

Source: Shutterstock.com

Complications of myocardial infarction

Restoring blood flow through the coronary artery in a timely fashion is vital to reduce the risk of serious ongoing problems; however, 30-day mortality after admission to hospital is still around 8–9%[3]

. Therefore, during hospital admission patients should:

- Be monitored in the first 24–48 hours for cardiac arrhythmias. Electrolyte levels (particularly potassium and magnesium) should be checked and supplemented if necessary, to reduce the risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Patients with late ventricular arrhythmia (i.e. occurring more than 48 hours after MI) are at higher risk of sudden cardiac death. In this case, antiarrhythmics (e.g. beta-blockers or amiodarone) or implantation of a cardio-defibrillator (i.e. an implantable device that treats abnormal heart rhythms) may need to be considered[25]

; - Have an ECG to assess left ventricular function, detect regional wall motion abnormalities, ensure the absence of ventricular thrombus and evaluate valve function[26]

; - Be monitored for uncontrolled or new-onset diabetes and, if the blood glucose is significantly raised, provided with an insulin infusion to acutely manage hyperglycaemia[27]

; - Be reviewed by the pharmacist who will advise the medical team accordingly to ensure both pre-admission and ongoing medicine is appropriate. This will include reviewing any medicine that may:

- Increase the risk of arrhythmia or prolong the QT interval (e.g. citalopram, lithium, quinine[28]

); - Increase the risk of fluid overload, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids;

- Increase bleeding risk, including NSAIDs, anticoagulants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs);

- Increase the risk of renal impairment or renal complications – this is particularly important when patients have received intravenous contrast therapy that may also cause acute kidney injury[20]

; - Be contraindicated in ACS — this may include treatments for other medical conditions (e.g. cancer chemotherapy with capecitabine)[12],[20]

.

- Increase the risk of arrhythmia or prolong the QT interval (e.g. citalopram, lithium, quinine[28]

- Be referred to the cardiac rehabilitation service.

Cardiac rehabilitation

According to the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR), cardiac rehabilitation is “the coordinated sum of activities required to influence favourably the underlying cause of cardiovascular disease, as well as to provide the best possible physical, mental and social conditions, so that the patient may, by their efforts, preserve or resume optimal functions in their community and through improved health behaviours, slow or reverse the progression of disease.”[29]

Evidence demonstrates better health outcomes for patients who engage with cardiac rehabilitation, including improved quality of life and reduction in the likelihood of a second MI. Consequently, all patients who have had an MI should be offered cardiac rehabilitation within ten days of discharge from hospital. In offering this, the cardiac rehabilitation team will make initial patient contact during the inpatient stay and/or telephone contact within a few days of hospital discharge. The BACPR guidance states that the patient should have access to the multidisciplinary team and be supported to undertake an individualised, structured exercise programme over a period of at least eight weeks[30]

. In addition to exercise, the programmes usually have a patient education component covering topics such as:

- Diet;

- Smoking cessation;

- Advice on driving, travel and work;

- Support for mental health and stress management techniques;

- Information on secondary prevention medicine[29],[31]

,[32]

.

Secondary prevention

Regardless of the method of reperfusion, it is essential to address lifestyle changes and ensure that medicines are appropriately prescribed to reduce the risk of the patient experiencing subsequent cardiac events[31],[32]

. Patients will be offered treatment from the drug classes discussed below.

Dual antiplatelet therapy

DAPT is used for the treatment of MI, but also helps reduce the risk of stent thrombosis. The stent is a foreign body that increases the risk of platelet aggregation and eventual thrombus formation. Treatment involves aspirin plus one of the following platelet inhibitors: ticagrelor, prasugrel or clopidogrel, and is usually recommended to be given for one year (see Table)[17]

. Over time, the body re-endothelises the stent (i.e. a layer of cells will grow over the stent), at which point there is a reduced thrombus risk[33]

.

Drug-eluting stents emit low doses of immunosuppressant drugs (e.g. sirolimus). This delays the process of re-endothelisation, thereby reducing restenosis (the recurring narrowing of blood vessels). However, this prolongs the potential period for stent thrombosis[33]

. After the one-year period, aspirin is continued indefinitely and, most commonly, the second antiplatelet agent is stopped. However, comorbidities and individual assessment of ischaemic versus bleeding risk will result in some variations for the one-year regimen. Examples of this include:

- Patients with an indication for anticoagulation — for example, atrial fibrillation where a combination of DAPT and a direct acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC) or warfarin may be indicated. In this combination of ‘triple therapy’, the DAPT regimen currently recommended is aspirin and clopidogrel for between one and six months; if a DOAC is used, the lower dose may be preferred[17],[34]

. However, the results of more recently published and ongoing studies will help to inform the best strategy in this scenario[35],[36]

; - Patients with ACS with elevated troponins may be prescribed rivaroxaban 2.5mg twice daily — this may be started as soon as possible after stabilisation of the acute event and co-administered with aspirin alone, or aspirin and clopidogrel. This is approved by NICE for the prevention of atherothrombotic events after ACS with elevated cardiac troponins[37],[38]

. Careful assessment of bleeding risk should be undertaken, and treatment reassessed at one year. - Patients at high risk of future ischaemic events — the prescriber may choose to continue a second antiplatelet agent beyond the one-year period. Ticagrelor is licensed and approved by NICE at the lower dose of 60mg twice daily for an extended period of up to three years[39],[40]

. Alternatively, a combination of aspirin 75mg and rivaroxaban 2.5mg (at a vascular protection dose) twice daily may be considered after one year of DAPT for secondary prevention in stable patients with coronary artery disease, or patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease at high risk of ischaemic events[41]

. This was approved by the Scottish Medicines Consortium in February 2019 and NICE in October 2019[42]

,[43]

.

| Drug/drug class | Administration | Usual dose | Duration | Contraindications | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (e.g. ramipril) | Small initial dose titrated to maximum tolerated. Started as soon as patient is haemodynamically stable. It can be commenced at night if concerned about risk of hypotension. Requires monitoring of renal function, including potassium, before starting, 1–2 weeks later, 1–2 weeks after this and then after any dose change. If cough is a problem, the ACE inhibitors can be switched to an angiotensin receptor blocker, such as candesartan. | Initial dose of ramipril 1.25–2.5mg per day. Dose should be titrated with monitoring of renal function and electrolytes to a target dose of 10mg/day (or maximum tolerated). | Lifelong. | Hypersensitivity or angioedema, bilateral renal artery stenosis, significant aortic stenosis. ACE inhibitors are teratogenic. | Cough, rash, renal impairment, increased potassium, hypotension. |

| Aspirin | 300mg initially should be given at the onset of symptoms and should be chewed to ensure quick systemic delivery. | 300mg initially then 75mg once per day (usually dispersed in water). | Lifelong. | Hypersensitivity — typically the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks for most individuals (e.g. rather than avoiding aspirin, if a patient has had previous peptic ulcer disease, this is usually treated concomitantly with a proton pump inhibitor for gastro-protection). | Increased bleeding time, dyspepsia, gastrointestinal bleeding. |

| Beta blocker (e.g. bisoprolol) | Small initial dose titrated to maximum tolerated. Start as soon as patient is haemodynamically stable. If beta blockers are contraindicated or not tolerated, providing the left ventricular function is not impaired, a rate-limiting calcium channel blocker (e.g. diltiazem or verapamil) can be used instead. | Initial dose of bisoprolol 1.25–2.5mg once per day. Provided the patient is in sinus rhythm, the dose can be titrated to achieve resting heart rate of around 60 beats per minute. For patients with atrial fibrillation, a target resting heart rate control of 80–100 beats per minute is preferred. | Lifelong for those with left ventricular dysfunction. For those without left ventricular dysfunction,12 months followed by a review. | Acute or decompensated heart failure, symptomatic hypotension or bradycardia, second- or third-degree heart block, severe asthma. Many patients with COPD will tolerate beta blockers with no deterioration in respiratory function. Caution in patients with diabetes as beta blockers can reduce hypoglycaemia awareness. | Cold extremities, bradycardia. Fatigue and headache are very common, but usually diminish after a few weeks of treatment. |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (e.g. eplerenone) | Started 3–14 days after myocardial infarction if reduced left ventricular function. Requires careful monitoring of renal function and potassium levels. | Usual starting dose is 25mg once per day (lower dose if renal impairment). | Long term. | Hyperkalaemia, severe renal impairment. | Gastrointestinal side effects, rash, hyperkalaemia, renal impairment, hypotension. |

| Glyceryl trinitrate (taken sublingually) | Spray or tablet sublingually (under the tongue). Ensure resting and in seated position before using. | One spray under the tongue. Wait five minutes. If the pain has not eased, continue to rest and take a further spray. If not relieved/easing at ten minutes call for help (dial 999). | Administer for chest pain or shortness of breath. | Severe hypotension, severe aortic stenosis, concomitant use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors (e.g. not within 24 hours of taking sildenafil). | Headache, facial flushing, hypotension, syncope. |

| Second antiplatelet after the myocardial infarction and percutaneous coronary intervention | Initial loading dose given. Duration is dependent on other treatment. |

| Dependent on other treatment. Duration is usually one year but may be reduced if high bleeding risk (dependent on type of stent). Prolonged therapy (after 12 months) may be given in selected cases (e.g. ticagrelor 60mg twice daily). | Hypersensitivity, active bleeding (e.g. intracranial bleed, severe hepatic impairment). | Increased bleeding (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, epistaxis, bruising and rash). Ticagrelor may cause breathlessness. |

| Statin (e.g. atorvastatin) | High-potency statins are recommended for secondary prevention. Atorvastatin does not need to be taken at night. Lipid profile monitoring and liver function should be conducted at 3 months, then 12 months. Regular monitoring of liver function after 12 months is not necessary. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends aiming for a 40% reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Other guidance suggests ‘target’ levels of an LDL less than 2mmol/L (or lower). | Atorvastatin 80mg once daily. Lower doses if drug interactions, previous statin intolerance, chronic kidney disease or patient preference. | Lifelong. | Acute liver failure. Statins are teratogenic. | Flatulence and other gastrointestinal disturbance, sleep disturbance, hyperglycaemia and myalgia. Rarely it may cause rhabdomyolysis. Always warn patients to report symptoms of unexplained muscle pain, weakness or cramps. |

Sources: Eur Heart J; Medicines compendium; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | |||||

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

An angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor should be prescribed to reduce ventricular remodelling and preserve ventricular function after MI. This should be initiated as early as possible following MI, starting at a low dose and up-titrating to the maximum tolerated dose considering blood pressure, renal function and electrolyte levels[31],[32],[44]

. This should be continued indefinitely. If an ACE inhibitor is not tolerated owing to side effects (e.g. an ACE cough), an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) may be suitable instead.

Beta-blocker

This should also be prescribed to reduce the risk of subsequent MI[31],[32]

. It should be initiated as early as possible following MI and titrated to the maximum tolerated dose, depending on heart rate and blood pressure. In patients with left ventricular impairment, a beta-blocker should be continued indefinitely, but in the presence of normal left ventricular function, it can be reviewed after one year[45],[31]

.

Statin

A high-intensity statin is prescribed to lower total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and improve plaque stability, thereby reducing risk of subsequent MI or stroke. NICE recommends a 40% or greater reduction in non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol which is potentially achieved with either atorvastatin 20–80mg once daily; rosuvastatin 10–40mg once daily; or simvastatin 80mg once daily (the latter is not recommended because of a higher risk of adverse effects). After ACS, the first-line treatment recommended by NICE is atorvastatin 80mg once daily (see Table)[46]

. Lower doses may be prescribed if there is a history of statin intolerance, renal impairment or patient preference. Lipid levels should be checked after three months to ensure sufficient cholesterol reduction has been achieved. Other guidelines recommend specific treatment targets aiming for an LDL cholesterol of 1.8mmol/L or lower for secondary prevention[48],[49],[50]

.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

Eplerenone, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, is added when an ECG shows evidence of left ventricular impairment with a reduced ejection fraction (≤40%) in patients who have symptoms of heart failure and/or diabetes[31],[51]

. The patient’s blood pressure, renal function and electrolytes must be assessed because this treatment would be in addition to the prescription of an ACE inhibitor (or ARB)[44]

. However, it should be noted that, in line with the NICE guideline for chronic heart failure in adults, if the patient is already prescribed spironolactone, the prescriber may continue this instead of making the switch to eplerenone[45]

.

Nitrate

Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate should be issued on hospital discharge, ensuring that the patient understands how and when this should be used. The patient should also have the ‘Ten-minute rule’ explained to them (i.e. if a combination of rest and treatment for ten minutes does not stop chest pain, the patient should call an ambulance)[52]

. Further details are given in the patient guide on the Pumping Marvellous website

[52]

.

Proton-pump inhibitor

Patients who are at an increased risk of bleeding who are prescribed DAPT or a DAPT/anticoagulation combination will also require a proton-pump inhibitor[17],[53]

. However, if clopidogrel is one of the antiplatelet agents used, the manufacturers recommend that omeprazole or esomeprazole use should be discouraged owing to the risk of interaction between the drugs which can potentially reduce levels of clopidogrel[20]

.

Risk factors for increased bleeding include:

- Previous gastric bleed;

- Age (>65 years);

- History of gastrointestinal reflux;

- High alcohol intake;

- Concomitant treatment with medicine that affects platelet function (e.g. SSRIs); additional anticoagulation; NSAIDs; or corticosteroids.

Best practice

Some patients being treated for myocardial infarction may not have taken regular medicine before. Therefore, pharmacists must ensure the following is covered when discussing medicines with patients:

- How to take their medicines

- Dose titration;

- Duration of therapy, in particular, antiplatelet therapy;

- Specific instructions for use of medicines (e.g. glyceryl trinitrate [GTN] spray).

- Why they need to take their medicines

- Including if, and when, any specific monitoring or blood tests are required.

- Information about other medicines

- Over-the-counter medicines to avoid such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or cough and cold remedies that contain sympathomimetic drugs (e.g. pseudoephedrine);

- Patients taking sildenafil (or equivalent alternatives) must be referred to their doctor for more information. They should be given advice on the risk of hypotension with nitrates and to avoid the use of GTN tablets or spray for 12–24 hours after any dose of sildenafil[19],[54]

; - The use of herbal remedies and whether there are any cautions or contraindications with respect to cardiovascular disease or other prescribed medicines[55]

.

- Other important practical information

- Common adverse effects — especially those that have an impact on quality of life — and how to deal with them;

- How to obtain further medicine supply;

- Prescription prepayment certificates;

- What to do if they miss a dose.

Pharmacists should also reinforce lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation (many community services will prove this as an enhanced service) as well as advice on diet, exercise, weight loss and sensible alcohol intake[31]

.

Author conflict of interest

Alison Warren has received consultancy/speaker fees from Amgen, Bayer, Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education, Napp, Novartis, Soar I-to-I and Sanofi. She has also received educational grants from Amgen, Bayer and Novartis, and the UK Cliniclal Pharmacy Association. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Peer-reviewed article

This article has been peer reviewed by relevant subject experts prior to acceptance for publication. The reviewers declared no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or in financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

References

[1] World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed March 2020)

[2] British Heart Foundation. Heart Statistics: British Heart Foundation Statistics Fact Sheet. 2011. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics (accessed March 2020)

[3] Nuffield Trust. How does UK’s acute myocardial infarction mortality rate compare internationally over time? 2018. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/chart/how-does-uk-s-acute-myocardial-infarction-mortality-rate-compare-internationally-over-time (accessed March 2020)

[4] Ambrose J & Singh M. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease leading to acute coronary syndromes. F1000Prime Rep 2015;7:08. doi: 10.12703/P7-08

[5] British Heart Foundation. Risk Factors for Heart and Circulatory Disease. 2015. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/risk-factors (accessed March 2020)

[6] Chapman A, Adamson P & Mills N. Assessment and classiï¬cation of patients with myocardial injury and infarction in clinical practice. Heart 2017;103:10–18. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309530

[7] Dorr M. Silent myocardial infarction: the risk beyond the first admission. Heart 2010;96(18):1434–1435. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.201384

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Assessment and immediate management of suspected acute coronary syndrome. 2016. Available at: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/chest-pain/assessment-and-immediate-management-of-suspected-acute-coronary-syndrome (accessed March 2020)

[9] Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39(2):119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

[10] Roffi M, Jean-Philippe C, Mueller C et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37(3):267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320

[11] Thygesen K, Alpert J, Jaffe A et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Eur Heart J 2019; 40(3):237–269. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy462

[12] British National Formulary. Treatment summary for the management of acute coronary syndromes. 2015. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/acute-coronary-syndromes.html (accessed March 2020)

[13] NHS. Primary PCI: Call to balloon time within 120 minutes. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/Scorecard/Pages/IndicatorFacts.aspx?MetricId=1119 (accessed March 2020)

[14] British Cardiovascular Society. Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project: 2019 summary report (2017/18 data). 2019. Available at: https://www.nicor.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/MINAP-2019-Summary-Report-final.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[15] NHS. Heart attack – treatment. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/heart-attack/treatment/ (accessed March 2020)

[16] NHS. Coronary angioplasty and stent insertion. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Coronary-angioplasty/ (accessed March 2020)

[17] Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2018;39(3):213–260. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419

[18] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ticagrelor for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes. Technology appraisal [TA236]. 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta236/chapter/1-guidance (accessed March 2020)

[19] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prasugrel with percutaneous coronary intervention for treating acute coronary syndromes. Technology appraisal [TA317]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta317/chapter/1-Guidance (accessed March 2020)

[20] Electronic medicines compendium. Latest medicine updates. 2020. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/ (accessed March 2020)

[21] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management. Clinical guideline [CG94]. 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg94/chapter/1-Guidance (accessed March 2020)

[22] NHS England and NHS Improvement 2017/18 and 2018/19 National Tariff Payment System. 2017. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/1044/2017-18_and_2018-19_National_Tariff_Payment_System.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[23] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Prasugrel (Efient): increased risk of bleeding. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/prasugrel-efient-increased-risk-of-bleeding (accessed March 2020)

[24] NHS. Coronary artery bypass graft. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronary-artery-bypass-graft-cabg/ (accessed March 2020)

[25] Kalanis Z, Svendsen J, Capodanno D et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in the emergency settings of acute coronary syndrome and revascularization: an European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document, endorsed by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA). EP Europace 2019;21(10)1603–1604. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz163

[26] British Society of Echocardiography: indications for echocardiography. Available at: https://bsecho.org/common/Uploaded%20files/Education/Protocols%20and%20guidelines/Indications%20for%20echocardiography.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[27] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hyperglycaemia in acute coronary syndromes overview. 2016. Available at: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/hyperglycaemia-in-acute-coronary-syndromes#content=view-node%3Anodes-ongoing-management-of-known-diabetes (accessed March 2020)

[28] Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS). Drugs to avoid. 2004. Available at: https://www.sads.org.uk/drugs-to-avoid/ (accessed March 2020)

[29] The BACPR Standards and Core Components for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Rehabilitation 2017 (3rd Edition). Available at: https://www.bacpr.com/resources/BACPR_Standards_and_Core_Components_2017.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[30] Cowie A, Buckley J, Doherty P et al. Standards and care components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation. Heart 2019;105:510–515. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314206

[31] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease. Clinical guideline [CG172]. 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG172 (accessed March 2020)

[32] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summary: MI Secondary Prevention. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/mi-secondary-prevention (accessed March 2020)

[33] McKavanagh P, Zawadowski F, Ahmed N & Kutryk M. The evolution of coronary stents. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2018;16(3):219–228. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1435274

[34] Gibson M, Mehran R, Bode C et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med 2016;375(25):2423–2434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611594

[35] Lopes R, Heizer G, Aronson R et al. Antithrombotic therapy after acute coronary syndrome or PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2019;380(16):1509–1524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817083

[36] Cannon C, Bhatt D, Oldgren J et al. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2017;377(16):1513–1524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454

[37] Mega J, Braunwald E, Wiviott Set al. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012;366:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112277

[38] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Technology appraisal guidance [TA335] Rivaroxaban for preventing adverse outcomes after acute management of acute coronary syndrome. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta335 (accessed March 2020)

[39] Bonaca M, Bhatt D & Cohen M. Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2015;372(19):1791–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500857

[40] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ticagrelor for preventing atherothrombotic events after myocardial infarction. Technology appraisal [TA420]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta420 (accessed March 2020)

[41] Eikelboom J, Connolly S, Boscj J et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377(14):1319–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709118

[42] Scottish Medicines Consortium: Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) – Advice. 2019. Available at: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/medicines-advice/rivaroxaban-xarelto-fullsubmission-smc2128/ (accessed March 2020)

[43] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Rivaroxaban for preventing major cardiovascular events in people with coronary or peripheral artery disease. Technology appraisal [TA607]. 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA607 (accessed March 2020)

[44] Think Kidneys. Position statement from Think Kidneys, the Renal Association, and the British Society for Heart Failure Changes in kidney function and serum potassium during ACEI/ARB/diuretic treatment in primary care. Available at: https://www.thinkkidneys.nhs.uk/aki/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/07/RA-BSH-2019-Changes-in-Kidney-Function-FINAL.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[45] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic heart failure in adults: management. NICE guideline [NG106]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG108 (accessed March 2020)

[46] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. Clinical Guideline [CG181]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181 (accessed March 2020)

[47] Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano A et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias> Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2020;41(1):111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

[48] Cannon C, Blazing M, Giugliano R et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2015;372(25):2387–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

[49] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Alirocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia. Technology appraisal [TA393]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA393 (accessed March 2020)

[50] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evolocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia. Technology appraisal [TA394]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA394 (accessed March 2020)

[51] Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207

[52] Pumping marvellous. A Marvellous Guide to using GTN – A patient’s guide. 2016. Available at: https://pumpingmarvellous.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/GTN-Marvellous-Guide.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[53] Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EMet al. ACCF/ACG/AHA. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2533–2549. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.445pmid:21131924

[54] Guys and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. Sildenafil Patient Leaflet from the male sexual health clinic. 2018. Available at: https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/resources/patient-information/cardiovascular/male-cardiovascular/sildenafil.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[55] Liperoti R, Vetrano D, Bernabei R & Onder G. Herbal medications in cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1168–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.078