Shutterstock.com

Malaria is a potentially life-threatening disease that is widely distributed throughout the tropical regions of the world, including Africa, Asia, and Central and South America[1]

. In 2016, there were around 216 million cases of malaria and around 445,000 deaths from malaria globally[2],[3]

.

Although malaria does not occur naturally in the UK, travel-associated cases are reported in people returning to the UK from malaria-endemic regions. Malaria is a notifiable disease in England and Wales and, based on data from 2008–2017, the mean number of malaria cases each year in the UK is around 1,558[4]

. Most of the imported cases of malaria in 2017 were acquired in Africa, with 66% (n=810/1,221) originating in Western Africa[5]

.

Malaria can be prevented through a combination of methods, including chemoprophylaxis. However, it has been reported that 85% of patients in the UK who had acquired malaria abroad had not taken chemoprophylaxis for one reason or another, implying that at-risk travellers may not be aware of the range of preventative strategies they can take to protect themselves[5]

.

Community pharmacists are accessible healthcare professionals and medicines experts; therefore, they are in a good position to advise individuals planning travel to malaria-endemic regions about the risks and how they can minimise their chance of contracting the disease.

Aetiology

There are five species of the Plasmodium parasite that can cause malaria in humans:

- Plasmodium falciparum;

- Plasmodium vivax;

- Plasmodium ovale;

- Plasmodium malariae;

- Plasmodium knowlesi.

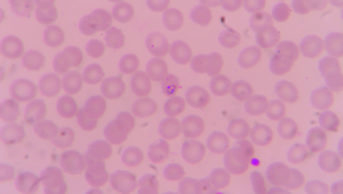

Of these species, P. falciparum is the most dangerous and accounts for the vast majority of malaria mortality globally[6]

. P. falciparum is the most common species of the genus Plasmodium in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2017, around 81% of imported cases of malaria into the UK were owing to P. falciparum, resulting in six deaths in the UK. These figures are consistent with imported P. falciparum malaria from previous years[5]

. In malaria-endemic areas outside Africa, P. vivax predominates[2]

. This species accounted for around 9% of malaria cases in the UK in 2017[5]

. Collectively, P. ovale, P. malariae

and

P. knowlesi

accounted for fewer than 10% of malaria cases in the UK in 2017[5]

.

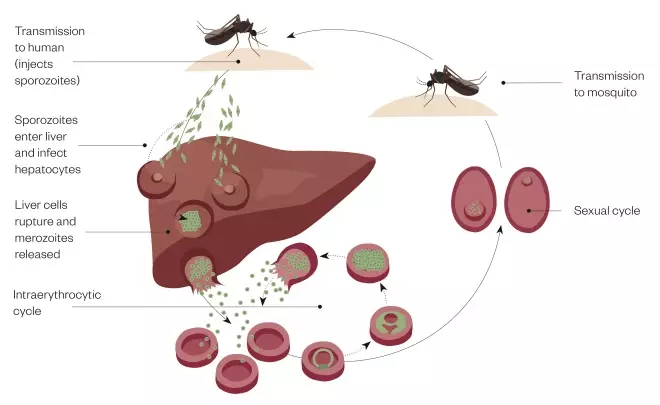

Pathophysiology

Malaria is transmitted to humans through the bite of a female Anopheles mosquito (the vector), which is infected with the Plasmodium parasite. When an infected mosquito feeds, sporozoites are injected into the bloodstream and migrate to the liver hepatocytes, where they develop into schizonts that rupture and release merozoites into the blood. The merozoites enter erythrocytes where they multiply asexually

until the cell bursts, releasing merozoites to infect other erythrocytes. This causes a steady increase in parasite

,[6]

,[7]

.

In the sexual part of the lifecycle, some of the merozoites in the red blood cells develop into male and female gametocytes, which are ingested by a mosquito as it feeds. These gametocytes fuse and develop into sporozoites, which then migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands and are transmitted to a human when the mosquito bites[6]

,[7]

(see Figure).

Figure: The malaria cycle in a human

Source: JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

The malaria cycle in a human

Prevention of malaria

When advising travellers to malaria-endemic areas, pharmacists and healthcare professionals should follow the recommendations made in the current report by Public Health England (PHE) on malaria prevention[6]

. The most important aspects of the report are reviewed in the sections below using the ABCD mnemonic[6]

:

- A — Awareness of risk;

- B — Bite prevention;

- C — Chemoprophylaxis;

- D — Diagnose promptly (and treat without delay).

Awareness of risk

Patient groups

Young children, immunosuppressed people (e.g. people with HIV/AIDS), pregnant women and older people are at an increased risk of severe forms of malaria[6]

. Pregnant women who contract malaria are at an increased risk of developing serious pregnancy complications, including premature birth, stillbirth and miscarriage.

People who once lived in endemic areas, but who are now settled in the UK, may mistakenly believe they are immune to malaria and so fail to take precautions[8]

. Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should advise these individuals that everyone must take precautions when travelling to malaria-endemic areas because no one is completely immune and natural immunity declines rapidly after leaving an endemic area[8]

.

Geography

The risk of contracting malaria is dependent on the area of travel and on other factors, including the time of year (malaria is highly seasonal in some areas and optimum conditions for transmission include high humidity), time of day (for example, Anopheles mosquitoes prefer to feed between dusk and dawn) and duration of stay (the longer the stay, the higher the risk)[6]

.

Pharmacists and healthcare professionals can identify country-specific malaria risk for patients through TravelHealthPro and TRAVAX[1]

,[9]

(see Box).

Box: How to identify the risk of malaria to a known destination

The following websites provide maps of destinations, indicating an estimation of the risk of malaria in that country and whether antimalarial prophylaxis is required.

It is important to note that although Public Health England (PHE) and Health Protection Scotland try to coordinate consistency of advice, recommendations do sometimes differ.

For healthcare professionals:

- In England, Wales and Northern Ireland — healthcare professionals are advised to refer to TravelHealthPro, which is maintained by the National Travel Health Network and Centre, commissioned by PHE.

- In Scotland — healthcare professionals should use TRAVAX, which is maintained and updated by the Travel and International Health Team of Health Protection Scotland.

For the general public:

- Fit for Travel

[10]

is the public version of TRAVAX.

Bite prevention

Effective bite prevention is essential; personal protection is recommended even in malaria-free areas to prevent other mosquito-borne diseases (e.g. dengue fever)[11]

.

Repellents

DEET-based (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) repellents may be used in adults and children aged over two months, as well as in pregnant women and women who are breastfeeding[6]

. Despite some public concern about safety, studies and clinical experience have concluded that there is a low risk of adverse effects when DEET is used according to product instructions[6]

,[10]

.

If DEET is not acceptable to the traveller (e.g. if they are allergic), there are useful alternatives containing icaradin (20% or above) and lemon eucalyptus (p-menthane-3,8-diol [PMD])[6]

,[10]

. However, few alternatives are as effective as high concentrations of DEET.

Homeopathic and herbal products should be avoided because there is a lack of evidence regarding efficacy in bite prevention[6]

,[10]

.

Behaviours

As the female Anopheles mosquito feeds from dusk until dawn, people should stay indoors during this time if possible and wear long sleeves, trousers and socks for added protection against bites[6]

. It is also recommended that people sleep in a well-screened, air-conditioned room or, otherwise, under an insecticide-treated mosquito net. On leaving the room, an insecticide spray or a plug-in insecticide vaporiser should be used[6]

,

[10]. People should not rely on insect repellents applied on the skin before going to sleep because they will not give adequate protection throughout the night.

Chemoprophylaxis

The most important change to the PHE guidelines for malaria chemoprophylaxis is that it is now rarely indicated in nearly all regions outside sub-Saharan Africa[12]

. This does not mean there is no risk of malaria in these countries, but that the risks are now perceived as being low for travellers. This is largely based upon the reporting of the malaria incidence among travellers returning to the UK, the levels of malaria in the local population and the likely incidence of adverse drug reactions to chemoprophylactic agents.

However, special patient groups — such as pregnant women, people who are immunocompromised and patients who lack normal spleen function — need chemoprophylaxis even if visiting low-risk areas[1]

,[6]

,[12]

. Special patient groups or individuals who are travelling on longer trips (for more than six months in malaria-endemic countries) should be considered for referral to a specialist travel clinic.

The choice of antimalarial agent should be based on the travel destination and tailored for the individual, taking into account potential risks and benefits to the traveller and likely concordance with the dosage regime. Therefore, individuals should have a detailed risk assessment by healthcare professionals to identify any potential cautions and contraindications.

Owing to extensive chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria being reported in all but a few World Health Organization regions, chloroquine with or without proguanil is now very rarely recommended as a prophylactic. Therefore, the three agents of choice, which all have equal efficacy, are: atovaquone with proguanil; mefloquine; or doxycycline[6]

. A brief summary of some important aspects of these prophylactic agents is given in Table. Unless otherwise indicated, this information is based on the PHE Advisory Committee on Malaria Prevention (ACMP) Guidelines 2019[6]

. For full prescribing information, reference should be made to the summary of product characteristics for each antimalarial drug and to the BNF/BNF for Children

[11]

.

| Antimalarial | Chemoprophylactic regime in adults | Cautions | Contraindications* | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atovaquone with proguanil (250mg/100mg combined preparation) | One tablet daily, starting one to two days before entering the endemic area. Continued while in the area and for seven days after leaving. | Lack of evidence on safety in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Diarrhoea and vomiting may reduce absorption of atovaquone. | Renal impairment if estimated glomerular filtration rate is less than 30mL/min/1.73m2. | Headache and gastrointestinal upset. |

| Doxycycline (100mg) | One tablet/capsule, starting one to two days before entering the endemic area. Continued while in the area and for four weeks after leaving. | Hepatic and renal impairment; myasthenia gravis and systemic lupus erythematosus; warn patient against excessive exposure to the sun. | Contraindicated in children aged under 12 years and in pregnancy and while breastfeeding. However, it may be considered as an option in special circumstances during pregnancy or breastfeeding, as detailed in the Public Health England Advisory Committee on Malaria Prevention’s 2017 guidelines[11] ,[13] | Oesophagitis and gastritis; may cause photosensitivity; Candida infections may occur. |

| Mefloquine (250mg) | One tablet each week, starting two to three weeks before entering endemic area. Continued while in the area and for four weeks after leaving. | Pregnancy and breastfeeding; cardiac conduction disorders; not recommended in infants weighing less than 5kg. | Allergy to quinine or quinidine; avoid in patients with psychiatric disorders, epilepsy or convulsions (or history of these conditions); avoid in patients with a history of blackwater fever; severe hepatic impairment. | Neuropsychiatric problems; vestibular disorders. |

*In all cases — includes allergy to the drug itself or ingredients in the formulation. Sources: Public Health England. Malaria prevention guidelines for travellers from the UK. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/malaria-prevention-guidelines-for-travellers-from-the-uk (accessed April 2019); National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and BNF. Malaria, prophylaxis. 2019. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/malaria-prophylaxis.html (accessed April 2019); Summary of product characteristics. Doxycycline 100mg Capsules. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4063/smpc#CONTRAINDICATIONS (accessed April 2019) [13] | ||||

Drugs for prophylaxis of malaria cannot be prescribed in NHS primary care, but may be supplied on a private prescription[11]

. Some pharmacists may supply atovaquone with proguanil, mefloquine or doxycycline on patient group directions. In 2017, atovaquone with proguanil became available to purchase over the counter as a pharmacy (P) medicine (Maloff Protect; Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Europe Ltd)[14]

.

When recommending malaria chemoprophylaxis, pharmacists must always refer to the recommended online databases (see Box) and be familiar with current ACMP/Scottish guidelines. Pharmacists should also counsel patients on taking their antimalarials correctly and on important side effects of these drugs. Chemoprophylaxis is not absolute and, therefore, pharmacists must stress the importance of personal protection against mosquito bites. Patients should be advised to remain alert for symptoms of malaria, especially within the first three months and for up to a year of returning from their trip[11]

.

It is good practice to keep a written record of all consultations involving the supply or recommendation of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis.

Diagnose promptly (and treat without delay)

The initial symptoms of malaria can be non-specific and can easily be mistaken for flu. If left untreated, malaria can rapidly get worse and be fatal.

Clinical features include[6]

:

- Fever;

- Chills;

- Sweats;

- Cough;

- Malaise;

- Headaches;

- Myalgia;

- Diarrhoea.

However, diagnosis of malaria cannot be confirmed or excluded by signs and symptoms alone. Differential diagnosis is wide ranging and also includes other travel-related infections.

The incubation period of P. falciparum malaria is typically 7–14 days but can be longer if the individual has partial immunity or if they have been taking antimalarials. P. falciparum causes the most severe form of malaria, which can quickly progress to life-threatening complications if left untreated[1]

.

For malaria caused by P. vivax or P. ovale, the incubation period is around 12–18 days, although hypnozoites may be reactivated after several months (or occasionally years) to cause illness[1]

.

Pharmacists should always enquire about recent travel in those presenting with fever. If the patient has visited a malaria-endemic area within the past year, urgent referral to a GP is needed.

The publishers work to ensure that the information is as accurate and up-to-date as possible at the date of publication; however, knowledge and best practice in this field change regularly.

References

[1] TravelHealthPro. Malaria. 2018. Available at: https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/factsheet/52/malaria (accessed April 2019)

[2] World Health Organization. Key points: world malaria report 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/malaria/media/world-malaria-report-2017/en/ (accessed April 2019)

[3] World Health Organization. World Malaria Day 2018 “Ready to beat malaria”: key messages. 2018. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272265 (accessed April 2019)

[4] Public Health England. Imported malaria in the UK: statistics. 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/imported-malaria-in-the-uk-statistics (accessed April 2019)

[5] Public Health England. Malaria imported into the United Kingdom: 2017 Implications for those advising travellers. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/722591/Malaria_imported_into_the_United_Kingdom_2017.pdf (accessed April 2019)

[6] Public Health England. Malaria prevention guidelines for travellers from the UK. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/malaria-prevention-guidelines-for-travellers-from-the-uk (accessed April 2019)

[7] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/biology/index.html (accessed April 2019)

[8] Stewart K. Malaria prevention in pharmacy. Chemist and Druggist. 2017. Available at: https://www.chemistanddruggist.co.uk/content/malaria-maloff (accessed April 2019)

[9] Health Protection Scotland & NHS National Services Scotland. TRAVAX. 2018. Available at: https://www.travax.nhs.uk/about-travax (accessed April 2019)

[10] Health Protection Scotland. Fitfortravel. 2019. Available at: https://www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/home (accessed April 2019)

[11] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and BNF. Malaria, prophylaxis. 2019. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/malaria-prophylaxis.html (accessed April 2019)

[12] TravelHealthPro. Updated guidelines for malaria prevention in travellers from the UK: 2017. Available at: https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/news/260/updated-guidelines-for-malaria-prevention-in-travellers-from-the-uk-2017 (accessed April 2019)

[13] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: doxycycline 100mg capsules. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4063/smpc#CONTRAINDICATIONS (accessed April 2019)

[14] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: MaloffProtectR. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/660/smpc (accessed April 2019)