Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Describe the symptoms children with anxiety can present with;

- Understand the different types of anxiety disorder and when they occur;

- Explain how childhood anxiety disorders are assessed and treated;

- List useful sources of information for patients and their families/carers.

Introduction

It is common for mental health problems to first occur in childhood. Global research has shown that a third of individuals experience their first mental health disorder before the age of 14 years, with anxiety disorders accounting for the majority of mental health conditions in this age group[1,2]. The median age of onset of mental health disorders as a whole is 11 years[3]. It has also been shown that approximately 7% of children worldwide have an anxiety disorder at any given time and around a quarter of people will have an anxiety disorder during their childhood years[4,5].

Diagnosis of anxiety disorders in childhood has increased over the past two decades and further increases were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic[6–9]. A complex interplay of psychosocial and environmental factors influence the development of anxiety disorders; genetics is also a strong contributing factor, with children of parents who have an anxiety disorder significantly more likely to develop anxiety[3,5].

Anxiety disorders can have significant effects on social functioning and educational attainment, with the potential for lifelong consequences. Having an anxiety disorder as a child increases the risk of having anxiety or depression as an adult. Additionally, experiencing anxiety in childhood also increases the risk of later suicide attempts, psychiatric admissions and abuse of alcohol or substances[10].

An understanding of these conditions and how they are treated is essential for any healthcare professional working with children and their families, regardless of specialty.

Overview of anxiety disorders

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases system (ICD-11) was updated in 2023 and now more closely mirrors the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5)[11,12]. The previous version of ICD (ICD-10) categorised conditions, such as obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, under the overarching heading of ‘anxiety disorders’. Now these conditions have their own separate categories in both classification systems and, as such, are not included in this article.

Figure 1 shows the median age of onset by anxiety disorder.

Typically, anxiety disorders present with emotional and physical symptoms. The context in which symptoms occur, the age at onset and their triggers help to distinguish between them.

Selective mutism

Selective mutism generally begins in early childhood, typically from around the age of two years and at around an important milestone, such as starting nursery or preschool. However, it can occur at any time — including in adulthood — and occasionally, symptoms originating in childhood continue into adulthood. In some cases, extreme anxiety makes speaking impossible. An inability to speak is most often experienced in social situations, such as school, or in unfamiliar environments, while speaking in other settings can be unaffected.

Separation anxiety disorder

Separation anxiety disorder is the development of extreme anxiety about being separated from a major attachment figure (usually parents or other caregivers)[11]. It is developmentally normal for young children to experience some anxiety about being separated from their attachment figures, typically beginning at around the age of 6–12 months and continuing until around 3 years of age. However, assessment is warranted if the anxiety is extreme or develops in older children. Children with extreme separation anxiety often present with physical symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and headaches. They may sleep poorly, have nightmares about being separated, insist on sleeping with a parent and/or experience thoughts of the attachment figure coming to harm. The distress may present as tantrums, social withdrawal or school refusal. Although symptoms can persist, they often resolve as the child approaches adolescence.

Specific phobias

Phobias are one of the most common anxiety disorders overall, with most cases in children occurring around the ages of 7–10 years[11]. A specific phobia is defined as an irrational or extreme fear of an object or a situation, generally grouped into the following categories[11]:

- Animals (e.g. spiders, dogs);

- Natural phenomena (e.g. fire, storms);

- Situations (e.g. flying, heights);

- Medical (e.g. blood, needles).

Again, excluding what is considered developmentally normal is important. For example, it is normal for young children to have some fear of the dark or of dogs and a normal response in these situations would be proportional, brief and respond to reassurance; however, if reactions are excessive, persistent and cause significant distress, leading to changes in behaviour that affects functioning, this departs from the norm and indicates a phobic disorder. Particularly in very young children, the fear response may present as a tantrum or cause a child to freeze. The intensity level of the response, coupled with the frequency and duration, are used to inform the diagnosis[11]. Typically, the main coping strategy is avoidance, which is seen in all ages[11]. A younger age at first onset is associated with an increased likelihood of having more than one phobia and, if symptoms persist throughout childhood and into adulthood, the phobia rarely spontaneously remits[11].

Social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder is an excessive fear or anxiety occurring in social settings with peers (e.g. holding conversations), or while being observed, such as answering questions in the classroom or eating in the school canteen. The person is overly concerned that they would embarrass themselves or be judged adversely by others and there may be intense physical symptoms, such as blushing and trembling[11]. Developmentally normal concerns about meeting new people or entering unfamiliar situations should be excluded. The dominant management strategy is avoidance, which may present subtly in young children (e.g. avoiding eye contact); however, as the child gets older and as social demands increase, the coping strategies may become more obvious, such as school refusal or withdrawing from activities that involve social interaction[11].

Generalised anxiety disorder

While the typical age of onset is in the early- to mid-30s[11], generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the more common anxiety disorders of late adolescence[2]. It is less common in younger children, which might be because their cognitive ability is not sufficiently developed to be able to worry[13]. GAD is characterised by uncontrollable, excessive and persistent worries about everyday events, such as school, family, friendships and the future. Younger children tend to worry more about safety, their health and the health of others, whereas older adolescents worry more about their performance and meeting the expectations of others[11]. Worries are accompanied by many physical symptoms affecting several body systems: headaches, abdominal pain, gastric upset and poor sleep[11]. Additionally, children with GAD frequently seek reassurance, experience distress if faced with uncertainty, and can be particularly sensitive to perceived criticism[14].

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is the fear of situations where escape may be difficult or where help may be unavailable. In the absence of a pre-existing diagnosis of panic disorder, age of onset is generally around the mid-20s, but it can occur in late adolescence[11]. Onset earlier in childhood is rare. While the presentation does not differ significantly across the age range, the triggers can vary: for example, adolescents may be more likely than adults to fear being outside the home or becoming lost[11].

Panic disorder

Panic disorder is characterised by the repeated unexpected occurrence of panic attacks (discrete episodes of intense fear accompanied by symptoms such as sweating, palpitations, shortness of breath or fear of imminent death) and the persistent worry of their re-occurrence. Most adolescents who experience an initial panic attack do not go on to develop the disorder[10]. The cognitive capacity for catastrophising about the significance of symptoms develops with age, meaning that panic disorder is rare in younger children. However, prevalence increases across adolescence, peaking in the early 20s.

Diagnosis

In the UK, the assessment and management of anxiety disorders in children is carried out by specialists within child and adolescent mental health services. An important consideration during the assessment process is determining whether symptoms deviate from developmentally normal fears and worries. The triggers for anxiety are generally normal experiences, such as putting a hand up in class, eating out, going to a party or sleepover, or being asked a question by a teacher. If reactions to such events are severe, disproportionate and persistent, or lead to a change in behaviour, such as school refusal, being unable to sleep alone or social withdrawal, then assessment is warranted.

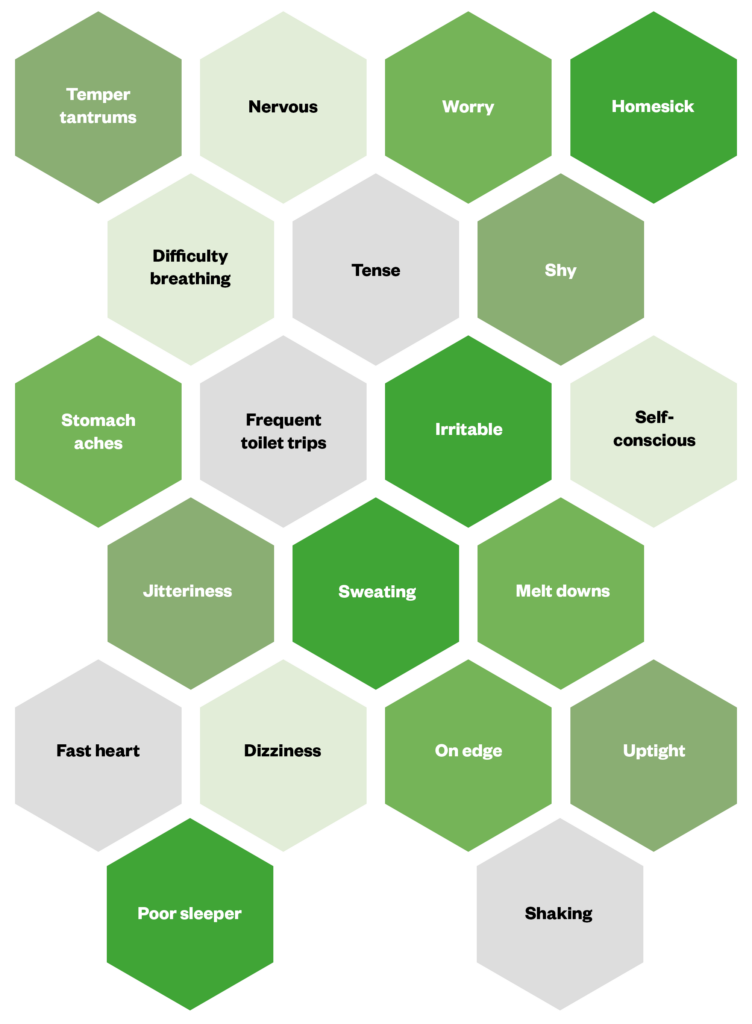

While it is important to assess the child, ideally on their own if possible, taking a detailed history from the parent or caregiver is equally important, as this will help provide a more complete picture. When a person describes their symptoms, they are likely to use words other than ‘anxious’ or ‘anxiety’ (see Figure 2).

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Comorbidity

Rates of comorbidity with other mental health conditions in young people with anxiety disorders is high, particularly the co-occurrence with another anxiety disorder[15]. There are many overlapping symptoms; therefore, an assessment should consider the possibility of a co-existing mental health condition and for an accurate anxiety diagnosis it is essential that other mental health conditions, speech and language problems, neurodevelopmental conditions, the use of drugs and alcohol, and other physical health conditions are all excluded as a cause of the presentation.

Diagnostic tools

Young people can find it difficult to verbalise their experiences, or they may feel embarrassed and be reluctant to share them with others. However, through careful and detailed evaluations, using a combination of self-report questionnaires and specialist clinician interviews, it is possible to accurately diagnose the individual anxiety disorders.

The risk of suicidal thoughts and ideas is increased in anxiety disorders and a comprehensive assessment of risk should form part of each mental health assessment[15].

It is a requirement for a diagnosis that symptoms must have been present for a sufficient period and be causing significant distress and impairment in functioning (see Table 1)[11].

There are many anxiety screening questionnaires available (see Table 2[16–19]). Some also include screening for other conditions and, not only are they a useful aid to an initial diagnosis, they can later be used again to provide a measure of response to treatment[15]. Questionnaires that measure impact on functioning can also be helpful.

Management of anxiety disorders

UK guidance is limited to the social anxiety disorder clinical guideline published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[20]. This guideline applies to all ages from school age to adults and recommends cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as the first-line treatment, advising against routinely offering pharmacological interventions for children and adolescents[20].

CBT is well established and the most widely available psychological therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders globally[4]. CBT is based on the premise that thoughts, feelings and behaviours are all connected. Challenging maladaptive thoughts through a gradual process of graded exposure, followed by reflection, facilitates new learning and allows the child to adapt and alter the way they perceive themselves and the world around them.

Other interventions, such as bibliotherapy and internet-based interventions, have a growing evidence base[15]. It remains unclear whether CBT is any more or less effective than other treatments, whether the method of delivery (e.g. group, individual, with parents or parent-only) affects outcomes, whether it is more or less effective for certain individuals (e.g. those with autism spectrum disorder), or what impact age and cognitive capacity may have on efficacy[15,21–23]. Although much of the published literature in this area has been carried out in children aged above seven years, there are also some positive findings in younger children[15].

There is evidence that pharmacological interventions are effective and generally well tolerated in children and adolescents[24–27]. Guidance in other countries, such as the United States and Canada, often includes more detailed recommendations for their use[4,28]. Serotonin is an important neurotransmitter within brain networks that is important in anxiety and in the cognitive processing of these emotions; therefore, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line medicines. There is currently no UK-licensed SSRI for the treatment of anxiety disorders in patients aged under 18 years, nor has NICE provided specific guidance on which SSRI to select — the choice is largely determined by considerations such as pharmacokinetics and potential for drug interactions. SSRIs used for other conditions (e.g. depression) in this age group are usually selected, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram and escitalopram.

The relative effectiveness of CBT, medication or a combination of both is unclear. Limited evidence indicates that a combination may be more effective than either treatment alone[25,29,30]. In practice, particularly in older children or when symptoms are severe, a combination treatment approach is often employed. It may be necessary to use medication on its own, for example when a young person is unable or unwilling to engage in psychological treatment, or when delays in accessing psychological therapy would be detrimental.

Gradual dose titration is recommended, generally beginning with half a usual starting dose for at least the first week (e.g. 12–25mg/day sertraline or 5–10mg/day fluoxetine) before titrating to dose ranges usually used in adults (e.g. 50–200mg/day sertraline or 20–60mg/day fluoxetine). While there is no specific minimum age limit, the use of SSRIs is more commonly seen in teenagers than in younger children and use in very young children is rare. Children with a learning disability require a more cautious approach to the use of medication as they are at greater risk of side effects, so initial doses are often even lower. Symptoms improve slowly and may require 12 weeks or longer for maximal effects to be seen[4].

SSRIs are generally well tolerated by children and adolescents with potential side effects similar to those seen in adults; however, behavioural activation and agitation occur with a higher frequency (see Box 1)[4,27]. This is one of the important counselling points (see Box 2).

Box 1: Behavioural activation with SSRIs

Behavioural activation occasionally occurs early in treatment (during the first month) or following a dose increase[4]. It is more common in younger children but will resolve after reducing dose or stopping. Symptoms include:

- Motor or mental restlessness;

- Insomnia;

- Impulsiveness;

- Talkativeness;

- Disinhibited behaviour;

- Aggression.

Box 2: Patient counselling and support

Important points to discuss with a young person who has been prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and their parent or carer are:

- The dose should be taken in the morning because SSRIs can cause insomnia in some people;

- SSRIs may worsen anxiety initially, but this is usually limited to the first week or two;

- Side effects that are common at start of treatment, but usually short lived, include headaches and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea;

- If behavioural activation occurs (see Box 1), or there are any new or worsening of disturbed feelings or thoughts of self-harm, this should prompt urgent discussion with the prescriber;

- Symptoms of serotonin syndrome, which is a rare but important condition, include fever, nausea, muscle twitches and confusion. If serotonin syndrome is suspected, the SSRI should be stopped and medical advice sought;

- SSRIs are not addictive; tolerance does not develop and there are no craving behaviours;

- Beneficial effects begin within a few weeks but could take up to 12 weeks to show the best effect;

- The treatment aim is for remission of symptoms and treatment should usually continue for 12 months after remission;

- Stopping an SSRI should be done gradually over several weeks to reduce the risk of discontinuation symptoms.

When response is poor, switching to a different SSRI should be considered while also undertaking a holistic review. Issues such as treatment adherence and the use of non-pharmacological interventions should be considered.

Widely used in adults as a treatment for anxiety, there is some (limited) evidence for the use of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) in children[27,31]. The SNRI duloxetine is licensed in the United States for GAD in patients aged 7–17 years and is included in treatment guidance in the United States and Canada[4,28]. However, owing to a greater side effect burden and a relative lack of data, SNRIs are considered a third-line treatment in the UK and are infrequently used, generally only in older adolescents[32]. The use of other medicines, such as benzodiazepines, pregabalin and propranolol, have known safety concerns, are not supported by evidence in this age group and are therefore not recommended[4,15,32].

An effective medication should be continued for at least 12 months following remission of symptoms[3,32].

Support needs of different age groups

It is important to involve parents and carers in anxiety management strategies, particularly with younger children. Children may benefit from social skills training and being taught coping skills. As parental anxiety can contribute to a child’s anxiety, it is also important to address this and any other needs of the parent or caregiver. Psycho-education is helpful for both the child and parent/caregiver, and providing guidance to parents/caregivers about how they can help their child’s anxiety, including positive parenting styles, is important[28].

Best practice

- Anxiety is an important and normal experience and is expected at different developmental phases during childhood as they develop an understanding of themselves and the world around them.

- Anxiety disorders are common in children and adolescents and are diagnosed when fears and worries are extreme, persistent and deviate from developmental norms and result in functional impairment.

- Anxiety disorders remain under-recognised and under-treated in children, and this has lifelong consequences.

- Noticing symptoms or behaviours in a child, or through discussions with parents and carers, should prompt further enquiry or signposting.

- Further research is needed and access to treatment must be improved; however, anxiety disorders can be effectively treated. Pharmacy professionals can help children and families by providing information and advice about the safe use of medication for anxiety in this age group.

Support and signposting

- The Young Minds website has a wealth of information for both young people and their parents: ‘Supporting your child with anxiety‘; ‘Social anxiety and school refusal‘; ‘Anxiety – a guide for young people‘;

- Mental Health Foundation: ‘The Anxious Child‘, a booklet for parents and carers wanting to know more about anxiety in children and young people;

- Royal College of Psychiatrists: ‘Worries and Anxieties for Parents and Carers‘;

- Anxiety UK: a national charity helping people with anxiety, including a helpline (03444 775 774) and text support line (07537 416 905);

- ‘All birds have anxiety‘ by Kathy Hoopmann;

- ‘Helping Your Child with Fears and Worries 2nd Edition: A self-help guide for parents‘ by C Creswell and L Willetts;

- Local NHS mental health trust websites, such as the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service.

- 1Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;27:281–95. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

- 2Penninx BW, Pine DS, Holmes EA, et al. Anxiety disorders. The Lancet. 2021;397:914–27. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00359-7

- 3Schiele MA, Domschke K. Epigenetics at the crossroads between genes, environment and resilience in anxiety disorders. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2017;17:e12423. doi:10.1111/gbb.12423

- 4Walter HJ, Bukstein OG, Abright AR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Anxiety Disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020;59:1107–24. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.005

- 5Freidl EK, Stroeh OM, Elkins RM, et al. Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety Among Children and Adolescents. FOC. 2017;15:144–56. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20160047

- 6Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017 [PAS]. NHS Digital. 2018.https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 7Theuring S, Kern M, Hommes F, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder in Berlin school children after the third COVID-19 wave in Germany: a cohort study between June and September 2021. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17. doi:10.1186/s13034-022-00552-0

- 8Strawn JR, Mills JA, Schroeder HK, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Infection and Characterization of Long COVID in Adolescents With Anxiety Disorders: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2022.12.027

- 9Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, et al. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

- 10Vallance AK, Fernandez V. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. BJPsych advances. 2016;22:335–44. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.114.014183

- 11Anxiety or fear-related disorders. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2023.https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1336943699 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 12American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- 13Songco A, Hudson JL, Fox E. A Cognitive Model of Pathological Worry in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23:229–49. doi:10.1007/s10567-020-00311-7

- 14Keeton CP, Kolos AC, Walkup JT. Pediatric Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Pediatric Drugs. 2009;11:171–83. doi:10.2165/00148581-200911030-00003

- 15Creswell C, Waite P, Hudson J. Practitioner Review: Anxiety disorders in children and young people – assessment and treatment. Child Psychology Psychiatry. 2020;61:628–43. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13186

- 16SCREEN for CHILD ANXIETY RELATED EMOTIONAL DISORDERS (SCARED). University of Pittsburgh Child and Adolescent Bipolar Spectrum Services. 2023.https://www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/resources/instruments (accessed Jun 2023).

- 17Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (and Subscales) (RCADS). Child Outcome Research Consortium. https://www.corc.uk.net/outcome-experience-measures/revised-childrens-anxiety-and-depression-scale-rcads/ (accessed Jun 2023).

- 18Lyneham HJ, Sburlati ES, Abbott MJ, et al. Psychometric properties of the Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale (CALIS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27:711–9. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.008

- 19Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;7:125–30. doi:10.1007/s007870050057

- 20Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, Assessment and Treatment [CG 159]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2013.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg159 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 21Zhou X, Zhang Y, Furukawa TA, et al. Different Types and Acceptability of Psychotherapies for Acute Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:41. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3070

- 22Yin B, Teng T, Tong L, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of parent-only group cognitive behavioral intervention for treatment of anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-03021-0

- 23James AC, Reardon T, Soler A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020;2020. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013162.pub2

- 24Ipser JC, Stein DJ, Hawkridge S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005170.pub2

- 25Wang Z, Whiteside SPH, Sim L, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Childhood Anxiety Disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:1049. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3036

- 26Strawn JR, Geracioti L, Rajdev N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adult and pediatric patients: an evidence-based treatment review. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2018;19:1057–70. doi:10.1080/14656566.2018.1491966

- 27Stefánsdóttir ÍH, Ivarsson T, Skarphedinsson G. Efficacy and safety of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2022;77:137–46. doi:10.1080/08039488.2022.2075460

- 28Bobbitt S, Kawamura A, Saunders N, et al. Anxiety in children and youth: Part 2—The management of anxiety disorders. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2023;28:60–6. doi:10.1093/pch/pxac104

- 29Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Sertraline, or a Combination in Childhood Anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2753–66. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0804633

- 30Piacentini J, Bennett S, Compton SN, et al. 24- and 36-Week Outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:297–310. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.010

- 31Strawn JR, Prakash A, Zhang Q, et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of Duloxetine for the Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:283–93. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.008

- 32Taylor DM, Barnes TR, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 14th ed. Wiley-Blackwell 2021. https://www.wiley.com/en-gb/The+Maudsley+Prescribing+Guidelines+in+Psychiatry,+14th+Edition-p-9781119772224 (accessed Jun 2023).