EYE OF SCIENCE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Aspergillus causes a broad range of diseases for which there are limited antifungal drug treatment options — a problem that is exacerbated by the emerging threat of antifungal drug resistance. As a result, there is a need for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to improve patient outcomes. Pharmacists should be aware of the various side effects and drug interactions associated with the use of antifungal drugs in the treatment of Aspergillus-related disease.

Aspergillosis

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous genus of mould that is commonly found in soil and decaying vegetation (see Box 1). The term ‘aspergillosis’ is used to describe the diseases caused by Aspergillus, but most commonly refers to those caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Other species that can cause human disease include Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus and Aspergillus niger

[1]

.

As part of its life cycle, Aspergillus releases large quantities of conidia (asexual spores) into the air and, therefore, can be found in both outdoor and indoor environments. Inhalation of Aspergillus conidia is generally a daily event, but only a small proportion of people develop clinical disease and are at an increased risk of developing aspergillosis (e.g. people with weakened immune systems and/or damaged lungs). Aspergillosis is not contagious and Aspergillus cannot be transmitted from person to person.

Owing to the insensitivity of fungal culture, the lack of routine, sensitive, non-culture diagnostic tests and the lack of a national surveillance programme, estimating the burden of aspergillosis in the UK is difficult. A 2017 study estimated that, every year in the UK, there are 3,288–4,257 cases of invasive aspergillosis, up to 3,600 cases of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and 110,667–235,070 cases of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) complicating asthma or cystic fibrosis[2]

.

Box 1: Where and when Aspergillus can be found

Aspergillus can normally be found around decaying vegetation. Aspergillosis may develop in healthy hosts following significant environmental exposure to Aspergillus spores, for example following the handling of tree-bark chippings[3]

. Everyday activities, such as gardening and household vacuum cleaning, can lead to the airborne release of Aspergillus spores.

In outdoor environments, Aspergillus can be found in[4]

:

- Soil;

- Compost heaps;

- Damp grain.

Inside buildings, Aspergillus can be found in:

- Damp insulation;

- Fireproofing material;

- Bedding;

- Behind sofas;

- In the corner of damp rooms;

- Dust;

- Air conditioning systems.

Most studies investigating seasonal variations in fungal exposure report an increase in airborne Aspergillus during the autumn and winter months in the Northern Hemisphere[4]

.

Types of aspergillosis

Aspergillus can cause a variety of clinical syndromes; variable host–pathogen interactions result in a spectrum of Aspergillus-related diseases, from hypersensitivity responses leading to ABPA through to invasive diseases associated with severely immunocompromised states[5]

.

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

In normal host lungs, inhaled conidia are cleared by epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages. Conidia escaping these host defences may germinate into branching filaments called hyphae, which is when Aspergillus becomes invasive. Inflammatory mediators released by alveolar macrophages lead to the recruitment of neutrophils, which can eliminate the hyphae[6]

.

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) most commonly occurs in severely immunocompromised patients and is characterised histopathologically by the invasion of lung tissue with hyphae[7]

.

Risk factors

Neutropenia is an important risk factor for the development of IPA and the risk correlates with neutropenia severity and duration. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and prolonged neutropenia following chemotherapy are significant risk factors (IPA occurs in 7–15% of these patients)[1]

.

IPA may also occur in non-neutropenic hosts, such as those receiving high-dose corticosteroids, solid organ transplant recipients (up to 20%), critically ill patients in intensive care units (up to 5%), patients with AIDS (4% at autopsy), patients with lung cancer (2.6%) and those hospitalised with COPD (1.3–3.9%)[8],[9],[10]

. It is also increasingly being recognised as a complication of severe influenza (19%), even in immunocompetent patients[11]

.

Symptoms

Classic symptoms of IPA occur late and include fever, pleuritic chest pain, haemoptysis (coughing up blood), cough and shortness of breath, with the disease typically progressing relatively rapidly over a period of days to a few weeks. Dissemination to other organs is seen in 5–10% of cases; this notably includes the brain, especially if patients are treated with the cancer therapy ibrutinib[12]

.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is critical to survival; however, a lung tissue biopsy is often not feasible. If left undiagnosed and untreated, IPA is almost always fatal. Diagnosis requires a combination of clinical, radiological and microbiological features, including detection of the antigen galactomannan[7]

. Even when diagnosed, however, IPA is associated with high mortality rates, particularly in HSCT recipients, where 12-week mortality rates above 50% have been reported[13]

.

Treatment

Voriconazole is recommended as first-line therapy for IPA, as it is associated with a lower mortality rate compared with amphotericin B[14]

. Isavuconazole is equally effective as voricanazole but less toxic[15]

. IPA should be treated with at least 12 weeks of antifungal therapy, although longer treatment courses may be required depending on clinical response and ongoing immunosuppression. Therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended during treatment with triazole antifungals[14]

(see Box 2).

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

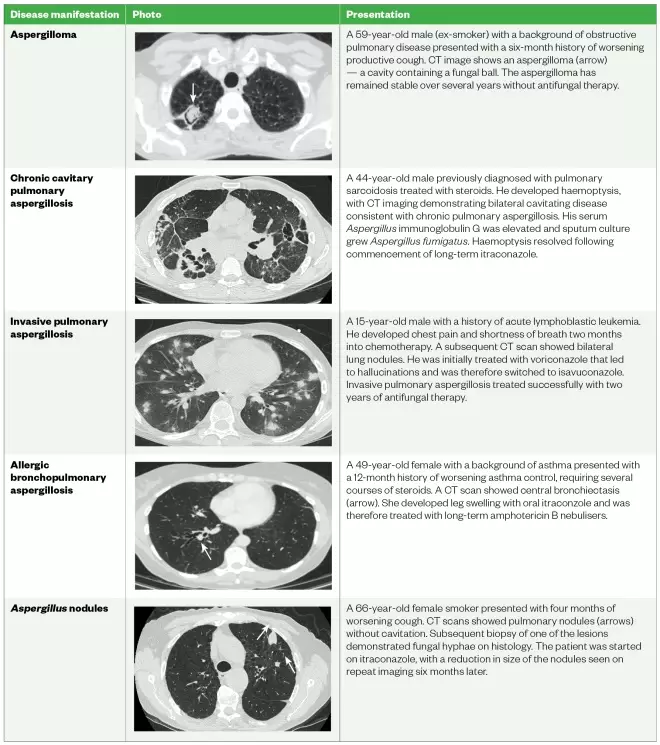

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is a term used to describe several diseases including aspergilloma, chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA), chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA) and Aspergillus nodules.

CPA is a chronic, progressive lung infection and the different manifestations of the disease are identified by characteristic radiographic findings (see Figure 1), although there is often considerable overlap between them[5],[16]

.

Table 1: CT images form patients with different manifestations of chronic pulmonary Aspergillosis

Source: Data taken from the National Aspergillosis Centre

An aspergilloma is a rounded mass consisting of Aspergillus hyphae, fibrin, mucus and cellular debris that forms within a pre-existing pulmonary cavity that has been colonised by Aspergillus

[17],[18],[19]

.

CCPA is a pattern of disease in which one or more thick-walled pulmonary cavities (with or without fungal balls [i.e. when fungal hyphae intertwine into dense collections]) develop over a period of several months[20]

. If left untreated, CCPA may progress and cause extensive fibrotic destruction of lung tissue; at this point it is classified as CFPA — a condition associated with significant respiratory compromise[21]

.

Single or multiple Aspergillus nodules may be present on imaging as solid nodules that can mimic other conditions, such as lung cancer[22]

. In general, CPA occurs in patients who are not overtly immunocompromised, but most have a history of pulmonary disease that has resulted in the formation of a cavity or bulla.

Risk factors

The most common diseases that predispose patients to CPA include pulmonary tuberculosis, non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection, ABPA, surgically resected lung cancer, pneumothorax with bulla formation and COPD[23]

.

Symptoms

Patients with CPA have symptoms that persist for months or years. These typically include weight loss, cough, shortness of breath and haemoptysis[20],[24]

.

Diagnosis

This requires a combination of characteristics that are all present for at least three months:

- One or more cavities with or without a fungal ball present or nodules on thoracic imaging;

- Direct evidence of Aspergillus infection (microscopy or culture from biopsy);

- An immunological response to Aspergillus and exclusion of alternative diagnoses.

Aspergillus antibody (precipitins or Aspergillus- specific immunoglobulin [Ig] G) is elevated in over 90% of patients.

Treatment

Long-term oral triazole therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for CPA. In cases of triazole intolerance or treatment failure, shorter courses of intravenous therapy with amphotericin B or an echinocandin may be used.

Surgical management may be an option in CPA patients with localised disease[25]

. Many patients are deficient in gamma interferon (IFN) or interleukin 12 and benefit from gamma IFN supplementation. See Box 2 for side effects of treatment.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

ABPA is a complex hypersensitivity response to inhaled Aspergillus.

Risk factors

This disease occurs almost exclusively in patients with asthma or cystic fibrosis[26]

. It is estimated that the prevalence of ABPA among patients with asthma is 1–2.5% and should be suspected in patients with poorly controlled or corticosteroid-dependant asthma[27]

.

Symptoms

These include fever, malaise, expectoration of mucus plugs and haemoptysis. Left untreated, ABPA can lead to progression of bronchiectasis or CPA.

Diagnosis

There is no single test that establishes the diagnosis of ABPA; however, the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology has proposed diagnostic criteria for ABPA that include the requirement of a predisposing condition (either asthma or cystic fibrosis), elevated total serum IgE level >1,000IU/mL and evidence of sensitisation to Aspergillus

[28]

.

Treatment

Short courses of systemic corticosteroids are used for exacerbations of ABPA, followed by long-term triazole therapy in many patients to reduce the fungal burden in those with frequent exacerbations or poorly controlled asthma[29],[30]

. See Box 2 for side effects of treatment.

Aspergillus bronchitis

This is a chronic, superficial infection of the lower airways (trachea and bronchi), without lung parenchymal invasion or allergic airway response, which typically occurs in patients who are not significantly immunocompromised. Although the pathophysiology is not completely understood, it is likely to involve anatomical alterations leading to ineffective airway clearance, together with subtle immune defects.

Risk factors

In one case series, 86% of patients diagnosed with Aspergillus bronchitis had underlying bronchiectasis and 70% used inhaled corticosteroids[31]

. The disease also occurs in patients with cystic fibrosis[32]

.

Symptoms

Patients present with persistent cough productive of purulent sputum, shortness of breath and a history of recurrent chest infections with limited or no response to antibiotic therapy.

Diagnosis

This requires repeated isolation of Aspergillus from sputum samples in a patient with typical symptoms, which have been present for at least four weeks[31]

.

Treatment

A four-month course of oral antifungal therapy is the mainstay of treatment. However, relapse is common (50%) and longer therapy may be required[31]

. See Box 2 for side effects of treatment.

Aspergillus rhinosinusitis

Similar to pulmonary disease, Aspergillus rhinosinusitis has both non-invasive and invasive manifestations.

Non-invasive forms of Aspergillus rhinosinusitis include fungal balls and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, both of which typically present with chronic rhinosinusitis symptoms. Nasal polyps are commonly associated with Aspergillus sensitisation (raised Aspergillus IgE) and can lead to nasal obstruction and local infection. Fungal balls usually affect only one sinus cavity

[33]

. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS) occurs in immunocompetent patients and arises as a result of a localised allergic reaction against colonising Aspergillus or other fungi. AFRS is characterised by the accumulation of eosinophilic mucin within the sinuses — a tenacious secretion that contains fungal hyphae and intense eosinophilic inflammation[34]

.

Invasive Aspergillus rhinosinusitis is defined by the presence of fungal hyphae within the mucosa, submucosa, bone or blood vessels of the paranasal sinuses[35]

. Invasive disease can be further sub-divided into acute and chronic forms[36]

.

Acute invasive Aspergillus rhinosinusitis

Acute invasive Aspergillus rhinosinusitis is an aggressive disease with a high mortality rate and often results in ocular and intracerebral extension (invasion into the eye and cerebrum). After establishing infection within one or more of the paranasal sinuses, fungi may slowly invade adjacent tissues, such as the skull base, orbit or brain.

Risk factors

It predominantly occurs in immunocompromised patients[37]

.

Symptoms

Patients with acute invasive Aspergillus rhinosinusitis typically present with nasal congestion, fever, sinus pain, epistaxis (nose bleeds) and may also experience facial numbness and diplopia if the cranial nerves are involved[38],[39]

.

Chronic invasive

Aspergillus

rhinosinusitis

Chronic invasive

Aspergillus rhinosinusitis is associated with relatively mild immunocompromised states.

Risk factors

These include people with diabetes and those using corticosteroids.

Symptoms

This is the indolent form of invasive sinus disease and patients experience chronic rhinosinusitis symptoms, such as mucopurulent nasal discharge, nasal congestion, sinus pain and impaired sense of smell, which persist for several months.

Diagnosis

The distinction between invasive and non-invasive disease can be made based on histopathological findings from biopsy samples.

Treatment

Topical intranasal corticosteroids may help to treat AFRS and antifungals are only used in cases with relapsing disease[40]

.

The treatment of aspergillosis varies depending on the specific disease (see Table 2). European guidelines on the management of aspergillosis, and more specifically for CPA, are available[14],[25]

.

| Disease | Primary treatment | Secondary treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Invasive aspergillosis |

|

|

| Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis |

|

|

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis |

|

|

| Aspergillus bronchitis |

|

|

| Sources: Clin Microbiol Infect [14], Eur Respir J [25] , Clin Transl Allergy [41] , Aspergillus & Aspergillosis Website[42] | ||

Box 2: Side effects of antifungal agents

Pharmacists must understand the side effects of antifungal agents.

Triazoles

These medicines can cause hepatotoxicity and peripheral neuropathy. Itraconazole may also cause cardiac failure and peripheral oedema, while voriconazole therapy is associated with severe photosensitivity and temporary visual impairment[43]

.

As substrates and inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes, triazoles can interact with a variety of drugs as inhibitors or substrates (e.g. rifampicin, carbamazepine, methadone), certain immunosuppressant drugs (e.g. cyclosporine, tacrolimus and sirolimus) and certain statins (e.g. simvastatin and atorvastatin). These interactions may lead to increased risk of toxicity of the concomitant medication or a significant reduction in the blood level of the triazole[44]

.

Amphotericin B

Renal impairment and electrolyte disturbances are well-recognised side effects of amphotericin B, although use of lipid formulations, such as liposomal amphotericin B reduces the risk of toxicity.

Echinocandins

These are generally well tolerated, although they may cause hepatotoxicity.

Drug interaction tools

Drug interactions, particularly with the triazole drugs, may provide an additional challenge during the treatment of aspergillosis. Online tools are available to check for antifungal drug interactions[45]

(see ‘Useful resources’).

Drug resistance

Triazole resistance is an increasing problem in two contexts:

- Environmental emergence secondary to spraying crops with triazole fungicides;

- During treatment of chronic and allergic aspergillosis.

The latter is more common in those with high fungal burdens, low antifungal drug levels and with itraconazole. Some species of Aspergillus are resistant to amphotericin B (notably A. terreus and A. nidulans), and A. niger isolates are resistant to itraconazole and isavuconazole[46]

.

References

[1] Marr KA, Carter RA, Crippa F et al. Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34(7):909–917. doi: 10.1086/339202

[2] Pegorie M, Denning DW & Welfare W. Estimating the burden of invasive and serious fungal disease in the United Kingdom. J Infect 2017;74(1):60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.10.005

[3] Arendrup MC, O’Driscoll BR, Petersen E & Denning DW. Acute pulmonary aspergillosis in immunocompetent subjects after exposure to bark chippings. Scand J Infect Dis 2006;38(10):945–949. doi: 10.1080/00365540600606580

[4] O’Gorman CM. Airborne Aspergillus fumigatus conidia: a risk factor for aspergillosis. Fungal Biology Reviews 2011;25(3):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2011.07.002

[5] Kosmidis C & Denning DW. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax 2015;70(3):270–277. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291

[6] Ben-Ami R, Lewis RE & Kontoyiannis DP. Enemy of the (immunosuppressed) state: an update on the pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus infection. Br J Haematol 2010;150(4):406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08283.x

[7] De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46(12):1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660

[8] Singh N & Paterson DL. Aspergillus i nfections in transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18(1):44–69. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.44-69.2005

[9] Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26(4):781–803; quiz 804–805. doi: 10.1086/513943

[10] Trof RJ, Beishuizen A, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ et al. Management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2007;33(10):1694–1703. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0791-z

[11] Schauwvlieghe AFAD, Rijnders BJA, Philips N et al. Invasive aspergillosis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6(10):782–792. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1

[12] Ghez D, Calleja A, Protin C et al. Early-onset invasive aspergillosis and other fungal infections in patients treated with ibrutinib. Blood 2018;131(17):1955–1959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-818286

[13] Baddley JW, Andes DR, Marr KA et al. Factors associated with mortality in transplant patients with invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50(12):1559–1567. doi: 10.1086/652768

[14] Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24(Suppl 1):e1–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002

[15] Maertens JA, Raad, II, Marr KA et al. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016;387(10020):760–769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01159-9

[16] Hayes GE & Novak-Frazer L. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis — where are we? And where are we going? J Fungi (Basel) 2016;2(2):E18. doi: 10.3390/jof2020018

[17] Shah R, Vaideeswar P & Pandit SP. Pathology of pulmonary aspergillomas. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2008;51(3):342–345. PMID: 18723954

[18] Daly RC, Pairolero PC, Piehler JM et al. Pulmonary aspergilloma. Results of surgical treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986;92(6):981–988. PMID: 3097424

[19] Judson MA & Stevens DA. The treatment of pulmonary aspergilloma. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2001;2(10):1375–1377. PMID: 11890350

[20] Denning DW, Riniotis K, Dobrashian R & Sambatakou H. Chronic cavitary and fibrosing pulmonary and pleural aspergillosis: case series, proposed nomenclature change, and review. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37(Suppl 3):S265–S280. doi: 10.1086/376526

[21] Kosmidis C, Newton P, Muldoon EG & Denning DW. Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis: a cause of ‘destroyed lung’ syndrome. Infect Dis 2017;49(4):296–301. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2016.1232861

[22] Muldoon EG, Sharman A, Page I et al. Aspergillus nodules; another presentation of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0276-3

[23] Smith NL & Denning DW. Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma. Eur Respir J 2011;37(4):865–872. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00054810

[24] Schweer KE, Bangard C, Hekmat K & Cornely OA. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2014;57(5):257–270. doi: 10.1111/myc.12152

[25] Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J 2016;47(1):45–68. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00583-2015

[26] Greenberger PA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;110(5):685–692. PMID: 12417875

[27] Greenberger PA & Patterson R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and the evaluation of the patient with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1988;81(4):646–650. PMID: 3356845

[28] Agarwal R, Chakrabarti A, Shah A et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: review of literature and proposal of new diagnostic and classification criteria. Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43(8):850–873. doi: 10.1111/cea.12141

[29] Agarwal R, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Behera D & Jindal SK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: lessons from 126 patients attending a chest clinic in north India. Chest 2006;130(2):442–448. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.442

[30] Stevens DA, Schwartz HJ, Lee JY et al. A randomized trial of itraconazole in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 2000;342(11):756–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421102

[31] Chrdle A, Mustakim S, Bright-Thomas RJ et al. Aspergillus bronchitis without significant immunocompromise. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1272:73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06816.x

[32] Shoseyov D, Brownlee KG, Conway SP & Kerem E. Aspergillus bronchitis in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2006;130(1):222–226. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.222

[33] Nicolai P, Lombardi D, Tomenzoli D et al. Fungus ball of the paranasal sinuses: experience in 160 patients treated with endoscopic surgery. Laryngoscope 2009;119(11):2275–2279. doi: 10.1002/lary.20578

[34] Luong A & Marple BF. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2004;4(6):465–470. doi: 10.1007/s11882-004-0013-5

[35] deShazo RD, O’Brien M, Chapin K & Soto-Aguilar M. A new classification and diagnostic criteria for invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123(11):1181–1188. PMID: 9366697

[36] Chakrabarti A, Denning DW, Ferguson BJ et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a categorization and definitional schema addressing current controversies. Laryngoscope 2009;119(9):1809–1818. doi: 10.1002/lary.20520

[37] Waitzman AA & Birt BD. Fungal sinusitis. J Otolaryngol 1994;23(4):244–249. PMID: 7996622

[38] Talbot GH, Huang A & Provencher M. Invasive Aspergillus rhinosinusitis in patients with acute leukemia. Rev Infect Dis 1991;13(2):219–232. PMID: 1904160

[39] Gillespie MB, O’Malley BW & Francis HW. An approach to fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in the immunocompromised host. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124(5):520–526. PMID: 9604977

[40] Loftus PA & Wise SK. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: the latest in diagnosis and management. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 2016;79:13–20. doi: 10.1159/000444958

[41] Denning DW, Pashley C, Hartl D et al. Fungal allergy in asthma — state of the art and research needs. Clin Transl Allergy 2014;4:14. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-4-14

[42] Aspergillus & Aspergillosis Website. Aspergillus bronchitis. 2016. Available at: https://www.aspergillus.org.uk/content/aspergillus-bronchitis (accessed July 2019)

[43] Bongomin F, Harris C, Hayes G et al. Twelve-month clinical outcomes of 206 patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. PLoS One 2018;13(4):e0193732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193732

[44] Girmenia C & Iori AP. An update on the safety and interactions of antifungal drugs in stem cell transplant recipients. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017;16(3):329–339. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2017.1273900

[45] Atherton G. Antifungal interactions — professionals. 2017. Available at: http://new.antifungalinteractions.com/index.php (accessed July 2019)

[46] Van Der Linden JW, Warris A & Verweij PE. Aspergillus species intrinsically resistant to antifungal agents. Med Mycol 2011;49(Suppl 1):S82–S89. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.499916