Centre Jean Perrin / Science Photo Library

Summary

There is no single cause for asthma, and a range of environmental and genetic factors are known to influence its development. These include premature birth and low birth weight and exposure to tobacco smoke (especially if the mother smokes in pregnancy). It is more common in prepubertal boys, but girls are more likely to remain asthmatic in adolescence.

A diagnosis of asthma in both children and adults is based on assessment of symptoms. The classic signs of asthma are wheezing (especially expiratory wheezing), breathlessness, coughing (typically in the early morning or at night time) and chest tightness. Children and adults with a high probability of asthma on assessment usually start a treatment trial with a corticosteroid such as beclometasone. Children and adults with an intermediate probability of asthma are assessed with lung function tests such as spirometry, peak flow and airway responsiveness to confirm the diagnosis.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways. Chronic inflammation causes an increase in airway hyperresponsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction that is often reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment[1]

.

It is estimated that more than 5.4 million people in the UK are currently diagnosed with asthma, of whom 1.1 million are children. In the UK, asthma causes 1,200 deaths each year, or one death from asthma every eight hours. This number has remained stable over the past few years despite raised awareness[2]

,[3]

.

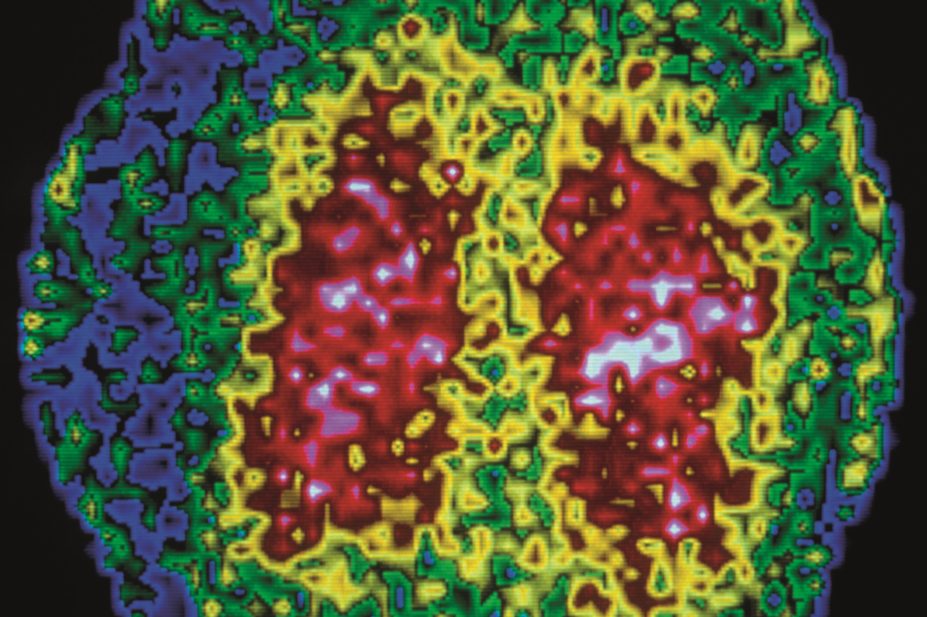

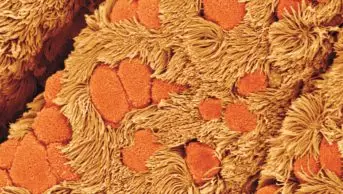

Pathophysiology

Asthma is usually mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) and precipitated by an allergic response to an allergen. IgE is formed in response to exposure to allergens such as pollen or animal dander[4]

. Sensitisation occurs at first exposure, which produces allergen-specific IgE antibodies that attach to the surface of mast cells. Upon subsequent exposure, the allergen binds to the allergen-specific IgE antibodies present on the surface of mast cells, causing the release of inflammatory mediators such as leukotrienes, histamine and prostaglandins. These inflammatory mediators cause bronchospasm, triggering an asthma attack.

If an attack is left untreated, eosinophils, T-helper cells and mast cells migrate into the airways[1]

. Excess mucus production caused by goblet cells plug the airway and, together with increased airway tone and airway hyperresponsiveness, this causes the airway to narrow and further exacerbates symptoms.

There is some evidence to suggest that airway remodelling can occur if asthma is poorly controlled over a period of years. Chronic inflammation causes bronchial smooth muscle hypertrophy, the formation of new vessels and interstitial collagen deposition, which results in persistent airflow obstruction similar to that seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[5]

.

Causes

Although there is no single cause of asthma, certain environmental and genetic factors are known to contribute to the development of the condition. These include:

- Family history of asthma (especially a parent or sibling) or other atopic conditions (for example, eczema or hayfever)

- Bronchiolitis in childhood — 40% of children exposed to respiratory syncytial virus or parainfluenza virus will continue to wheeze or have asthma into later childhood[1]

- Exposure to tobacco smoke, particularly if the mother smokes during pregnancy

- Premature birth

- Low birth weight

- Occupational exposure to plastics, agricultural substances and volatile chemicals, such as solvents. Asthma is more prevalent in industrialised countries

- A body mass index of 30kg/m2 or more

- Bottle feeding — evidence shows that if an infant is breastfed there is a decreased risk of wheezing illness compared with infants who are fed formula or soya-based milk feeds[3]

Environmental and cultural factors in recent decades, such as changes in housing, air pollution levels and a more hygienic lifestyle (reducing early exposure to allergens), may also increase the risk of asthma.

Asthma is more common in prepubertal boys, but boys are more likely to grow out of their asthma during adolescence than girls[1]

.

Phenotyping is becoming increasingly important for clinicians in determining why some people are predisposed to develop asthma and others are not. Furthermore, it is believed that a person’s phenotype may also contribute to the way he or she responds to treatment[6]

. For example, variations in the gene that codes for beta-adrenoceptors have been linked to differences in how cells respond to beta-agonists. In the future, as more information emerges, it may be possible to tailor treatments for individual patients to enhance response — which is particularly important as more high-cost, highly specific medicines are being developed[3],[6]

.

Clinical features

There are many factors likely to trigger an asthma attack, and potential causes will vary between patients. Possible triggers include: the common cold; allergens (e.g. house dust mites, pollen); exercise; exposure to hot or cold air; medicines (e.g. NSAIDs); and emotions such as anger, anxiety or sadness.

The classic signs of asthma are wheezing (especially expiratory wheezing), breathlessness, coughing (typically in the early morning or at night time) and chest tightness. Wheezing that occurs as a result of airway bronchoconstriction and coughing are likely to be caused by stimulation of sensory nerves in the airways.

In a severe exacerbation, when there is severe obstruction of the airway, wheeze may be absent and the chest may be silent on auscultation (listening to the chest). In such cases, other signs such as cyanosis and drowsiness may be present, and the patient may be unable to complete full sentences. Severe exacerbations of asthma are medical emergencies.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of asthma is based on medical history, physical examination, lung function testing and response to medication (see ‘Diagnosis of asthma’). There is no gold standard test that can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnosis of asthma[1]

Clinical features that increase the probability of asthma

- More than one of the following symptoms: wheeze, cough, difficulty breathing, chest tightness, particularly if these are frequent and recurrent; are worse at night and in the early morning; occur in response to, or are worse after, exercise or other triggers; occur apart from colds; are associated with taking aspirin or beta-blockers in adults

- Personal history of atopic disorder

- Family history of atopic disorder and/or asthma

- Widespread wheeze heard on auscultation

- History of improvement in symptoms or lung function in response to adequate therapy (in children)

- Otherwise unexplained peripheral blood eosinophilia, or low forced expiratory volume in one second or peak expiratory flow (in adults)

Clinical features that lower the probability of asthma

- Symptoms with colds only

- Isolated cough with no wheeze or difficulty breathing, or history of moist cough (in children)

- Chronic productive cough with no wheeze or difficulty breathing (in adults)

- Prominent dizziness, light-headedness, peripheral tingling

- Repeatedly normal physical examination of chest when symptomatic

- Normal peak expiratory flow or spirometry when symptomatic

- Cardiac disease (in adults)

- Voice disturbance (in adults)

- History of smoking for more than 20 pack-years (in adults)

Children and adults with a high probability of asthma on assessment usually start a treatment trial, where their response is assessed using spirometry. Children and adults with an intermediate probability of asthma usually have lung function tests conducted, such as spirometry, peak flow and airway responsiveness.

Spirometry can be used to measure lung function and is a good guide to diagnosing asthma in adults. It is not always definitive; normal findings do not exclude a diagnosis of asthma if the patient is well at the time of testing. The spirometric measures used in the diagnosis of asthma are:

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) — the total volume of air expelled by a forced exhalation after a maximal inhalation

- Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) — the volume of air expelled in the first second of a forced exhalation after maximal inhalation

- FEV1/FVC ratio

An FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.7 is suggestive of airway obstruction, which can increase the probability of asthma, but it can also be caused by conditions such as COPD.

Peak expiratory flow using a peak flow meter measures the resistance of the airway. Although it is not as accurate as spirometry, it can be used to demonstrate variability of lung function throughout the day. Measurements should be taken in the morning and evening (as a minimum) and recorded in a diary to see if there is diurnal variability. Readings are dependent on technique and expiratory effort, therefore the best of three expiratory blows from total lung capacity should be recorded during each session. Peak flow diaries are better for monitoring patients with an established diagnosis of asthma rather than for making an initial diagnosis[1],[3]

.

Assessment of airway responsiveness using inhaled mannitol or methacholine is used for diagnosing patients with normal or near normal spirometry who have a baseline FEV1 of less than 70% of that predicted using population data. Both drugs induce bronchospasm[1],[3]

. A fall in FEV1 of more than 15% following a test with mannitol is a specific indicator for asthma. This assessment is useful for distinguishing asthma from other common conditions that can be confused with asthma (for example, rhinitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux, heart failure and vocal cord dysfunction).

A treatment trial in adults involves a patient being prescribed a six-to-eight week trial of inhaled beclometasone 200µg (or equivalent) twice a day, or two weeks of oral prednisolone 30mg daily. An improvement in FEV1 of 400ml or more following the trial is strongly suggestive of an underlying diagnosis of asthma. Spirometric assessment after a treatment trial is more effective for patients with known airflow obstruction, and is less helpful for patients who had near normal lung function before the trial.

Non-invasive testing of sputum eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide concentration can also help guide a diagnosis of asthma. A raised sputum eosinophil count (>2%) is seen in around 70–80% of patients with uncontrolled asthma. However, patients with COPD or chronic cough may also exhibit abnormal levels of eosinophils and the test should not be used for definite diagnosis[7]

. Sputum eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide concentration are not routinely measured in general practice, but are in designated difficult asthma clinics[3]

. An exhaled nitric oxide level of more than 25 parts per billion supports a diagnosis of asthma.

Assessing asthma control

Many people with asthma do not have their condition well controlled. A survey of 8,000 people with asthma in Europe between July 2012 and October 2012 found that despite 91% of patients considering themselves as having well controlled asthma, only 20% of cases were controlled according to standards set out by national and international guidance[8]

.

The aim of asthma management is to achieve and maintain complete control of the disease. This is defined as having:

- No daytime symptoms or night time awakening due to asthma

- No need for rescue medication

- No exacerbations

- No limitations on activity including exercise

- Normal lung function

- Minimal side effects from medication

It is important that control of asthma is measured objectively. One effective way to assess the level of control is the Asthma control test questionnaire (available from asthma.com). This validated five-point questionnaire is a simple and easy way for patients to self assess their asthma control and guide healthcare professionals to develop a treatment plan in accordance with the results obtained[1]

.

References

[1] British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma. Clinical Guideline 141. London: BTS. October 2014.

[2] Royal College of Physicians (London). Why asthma still kills. London: RCP. May 2014.

[3] Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Geneva: GINA. 2014.

[4] Barnes P. Similarities and differences in inflammatory mechanisms of asthma and COPD. Breathe 2011;7:229–238.

[5] Dournes G & Laurent F. Airway remodelling in asthma and COPD: findings, similarities and differences using quantitative CT. Pulmonary Medicine 2012.

[6] Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat Med 2012;18:716–725.

[7] Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophilia counts: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2002;360:1715–1721.

[8] Price D, van der Molen T, Fletcher M. Exacerbations and symptoms remain common in patients with asthma control: a survey of 8000 patients in Europe. Abstract presented at the European Respiratory Society conference 2013.

You might also be interested in…

Helping respiratory patients breathe easy

Asthma therapies get personal