Science Source / Science Photo Library

In 2015, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued a patient information booklet for women of childbearing age warning about the risks associated with valproate use during pregnancy. The risks highlighted are birth defects including spina bifida, facial, skull and organ malformations, and limb defects. The risk is estimated at 10% compared with 2–3% in a population where the mothers do not suffer from epilepsy[1]

.

There are numerous formulations of valproate, including sodium valproate (Epilim) and valproic acid as semi-sodium salt (Depakote and Convulex). Both sodium valproate and semi-sodium are metabolised to valproic acid, otherwise known as valproate, which is the active compound. Sodium valproate is licensed for all forms of epilepsy[2]

. Semi-sodium (Depakote) is licensed for the treatment of mania. An unlicensed indication for migraine prophylaxis is also listed in the BNF for both sodium valproate and semi-sodium[2]

.

In clinical practice they are both also commonly used in the treatment of bipolar disorder. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines lists the indications as mania, hypomania, bipolar depression and prophylaxis of bipolar disorder, while noting that the licensed indications are restricted to epilepsy for sodium valproate and acute mania for semi-sodium valproate[3]

. Therefore, other than for epilepsy or mania, routine prescribing of either sodium valproate or semi-sodium should not be seen in clinical practice.

This article, a timely consideration of the use of valproate in the treatment of bipolar disorder and, with reference to the current evidence base, will discuss: what it is licensed for, what it is used for in clinical practice, and why it is used long-term in female patients. The article will investigate safety issues, risks and benefits associated with valproate use and assess how these compare with alternative treatments. It will also highlight what information patients and healthcare professionals need to know about valproate use in bipolar disorder.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Bipolar disorder or Bipolar Affective Disorder (BPAD), previously known as manic depression, is a mood disorder characterised by extreme switches between depressive and manic episodes. Like unipolar depression (the type most people are familiar with) the main symptoms of bipolar depression are low mood, decreased energy and loss of interest. Difficulty concentrating, sleep disturbances, social withdrawal, feelings of guilt and suicidal thoughts, all of which affect normal functioning, are other well-known indicators. Unlike unipolar depression, bipolar depression has a rapid onset, can be more severe, more frequent and last for a shorter time than unipolar depression. It also has a different response to drug treatment[3]

.

Mania symptoms include feelings of extreme elation, irritability, grandiosity and a reduced need for sleep. People experiencing these symptoms may exhibit uncharacteristic or dangerous behaviours, such as excessive spending, gambling, drug taking or promiscuity. Someone with mania may also experience hallucinations or delusions. Hypomania is similar to mania but less severe and does not affect day-to-day functioning to the same degree. Some people describe hypomania as a desirable state because they can be productive and require little rest during these periods[4]

. However, there is a risk of switching to full-blown mania or crashing into depression.

There are different types of bipolar disorder and diagnosis centres on symptoms, severity, duration and the number of times episodes are experienced. The different types referred to are:

- Bipolar I disorder: an individual experiences periods of mania switching with depression.

- Bipolar II disorder: hypomania is experienced with periods of depression.

- Rapid cycling bipolar: four or more episodes of mania, hypomania, depression or mixed states are experienced in a 12-month period.

- Mixed bipolar state: symptoms of mania and depression are experienced at the same time.

- Cyclothymia: milder form where hypomania is experienced alternating with less severe depression.

Treatment

Bipolar disorder treatment is generally directed at the different phases of the condition: acute manic or mixed episodes, depressive episodes, and long-term maintenance. There are four main groups of medicines used in the treatment of bipolar disorder: antidepressants, lithium, antiepileptics used as mood stabilisers, and antipsychotics. More detailed information about these groups is provided in later sections.

Treating bipolar depression

Antidepressants are generally used to treat episodes of depression and not as long-term prophylaxis for bipolar disorder because there is a risk of triggering a switch to mania. Bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed as unipolar depression and antidepressant use has been shown to worsen the outcome in patients when compared with mood stabilisers[5]

. The treatment recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as the most clinically- and cost-effective option for moderate or severe bipolar depression is a combination of fluoxetine (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) and olanzapine (an atypical antipsychotic)[6]

. In the United States, a combination product of olanzapine and fluoxetine called Symbyax is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is widely used for both bipolar disorder and treatment-resistant depression. The doses of the combined preparation capsule range from 3–12mg of olanzapine and 25–50mg of fluoxetine (i.e. 3mg/25mg, 6mg/25mg, 6mg/50mg, 12mg/25mg, 12mg/50mg to be taken once daily in the evening). Equivalent doses using the individual drugs in the UK would be olanzapine 5mg and fluoxetine 20mg, or olanzapine 10mg and fluoxetine 40mg.

There is evidence for the effective treatment of bipolar depression with quetiapine (an atypical antipsychotic)[6],[7]

. Doses of 300–600mg daily of quetiapine were found to be effective and well-tolerated[8]

. If a patient is unresponsive to either of these treatments, or prefers an alternative, NICE recommends that lamotrigine (an antiepileptic) is used as an alternative to olanzapine (with or without fluoxetine) or quetiapine[6]

.

Lamotrigine is licensed for preventing depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder[2]

. Prior to commencing lamotrigine, a full blood count with urea, electrolytes and liver function tests should be carried out[6]

. It requires slow initiation starting at 25mg once daily for 14 days, then 50mg daily in 1–2 divided doses for another 14 days, then 100mg daily in 1–2 divided doses for a further 7 days. The usual maintenance dose may be 200mg daily in 1–2 divided doses, up to a maximum of 400mg for monotherapy[2]

. If lamotrigine is being used alongside valproate, initiation is even slower, starting with 25mg on alternate days for 14 days before 25mg once daily for 14 days and so on, as described above. The maximum dose if used with valproate would be 200mg daily[2]

.

Patients should be warned to look out for, and immediately report, any signs of skin rashes because this may be a serious life-threatening skin rash such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, which occurs in 1 in 1,000 patients being treated for bipolar disorder[9]

. The appearance of rashes appears to be associated with higher initial doses, exceeding recommended dose escalation, and concomitant valproate. Therefore, slow titrations are advised to reduce this risk.

Treating mania and hypomania

Healthcare professionals may see people presenting more frequently with mania than any other episode, particularly in hospital settings. Inpatient admissions tend to occur when someone has become a risk to themselves, or if their behaviour is uncharacteristic or bizarre enough to generate attention. Antipsychotics are widely used and are the mainstay treatment for mania and hypomania[7]

. Olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine are commonly used[2]

, and NICE also recommends haloperidol as a treatment option[6]

. These four medicines, and aripiprazole, are all licensed for mania as well as schizophrenia. An alternative is asenapine (Sycrest; see ‘Box 1 Asenapine counselling’ for the method of administration), a second generation antipsychotic specifically licensed for treating mania but with no licence for schizophrenia in the UK[2]

. If a patient is already taking an antidepressant when they start to experience a hypomanic or manic episode, it is recommended that this is stopped[7]

or at least consideration should be given to stopping. Whether the antidepressant is stopped or not, an antipsychotic should be offered[6]

. Doses of antipsychotics tend to be higher in mania treatment than doses used to control schizophrenia (e.g. the maximum dose of quetiapine to treat mania is 800mg whereas 750mg is the maximum for schizophrenia). However, higher doses are generally used for shorter periods. Depending on the severity of the episode, antipsychotics can be used in combination with benzodiazepines for severe conditions, particularly if rapid treatment by injection is required. When oral medication can be taken, antipsychotics or valproate are recommended. For milder episodes, an antipsychotic or valproate, or another mood stabiliser such as lithium or carbamazepine, are recommended[10]

. Lamotrigine is not recommended in mania or hypomania[6]

.

Box 1: Asenapine counselling

Asenapine is a second generation antipsychotic licensed for the treatment of moderate to severe manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder. The tablet is sublingual and patients should be counselled in the following points:

- It should not be stored anywhere other than in the foil blister pack;

- The tablet should not be removed until the patient is ready to take it;

- Dry hands should be used when handling the tablet;

- The tablet should not be pushed through the pack, but carefully peeled back to remove;

- The tablet should be placed under the tongue and allowed to dissolve completely, which should only take a few seconds;

- The tablet should not be crushed, chewed or swallowed;

- No food or drink should be taken for ten minutes after the tablet has been taken;

- If taking any other medicines asenapine should be taken last.

If a patient is unable to take asenapine using this method it may not be a suitable treatment because biovailability when swallowed is less than 2%[11]

.

A 12-week trial comparing the effectiveness of lithium and valproate in the treatment of acute mania in patients with bipolar I disorder demonstrated a 65.5% remission rate with lithium and 72.3% with valproate[12]

. In this study, 300 patients were randomised to either lithium (starting at 400mg/day) or valproate (starting at 20mg/kg/day) for 12 weeks. Without treatment, a manic episode may last from three to six months. This study also demonstrated comparable adverse events reported at 44% for both treatments. The most commonly reported adverse events for both treatment groups were tremor, nausea and weight gain. Tremor and nausea were most frequently reported in the lithium group, while fatigue, nausea and weight gain were reported the most in the valproate group. Serious adverse events and discontinuation because of these was higher in the lithium group but this was not statistically significant[12]

.

Treatment for mania should be reviewed after four weeks and remission should be seen within three months. At this stage, maintenance treatment should be discussed. Some people prefer not to continue with pharmacological treatments and are able to monitor their condition using diaries, psychotherapy or other methods. A good level of insight is required to effectively manage bipolar disorder in this way. For others, pharmacological treatment is the best way to prevent relapse (see ‘Figure 1: Treatment algorithm for mania/hypomania’).

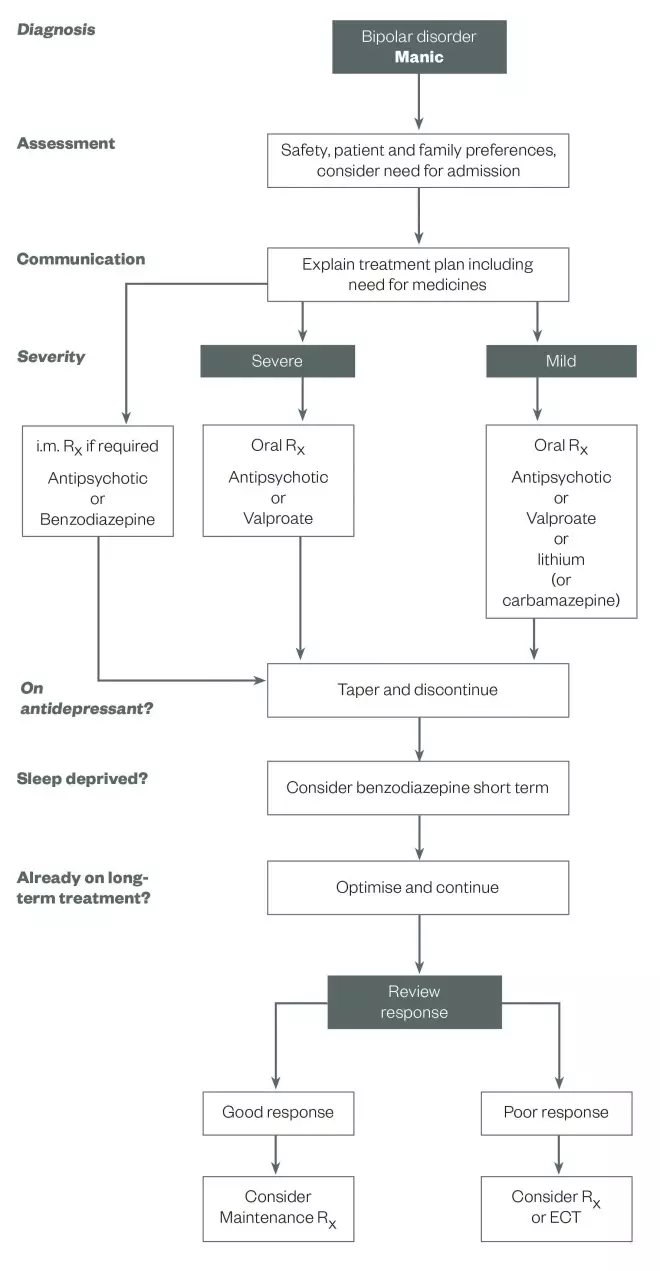

Treatment algorithm for mania/hypomania

Source: Reproduced with permission. Goodwin GM. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2009;23:346–388

For patients with mania, the severity and whether they are on antidepressants, sleep deprived or on long-term treatment affects the treatment plan. This algorithm outlines key practice points that can help guide treatment in these patients.

Lithium maintaintenance treatment

For long-term monotherapy, particularly when manic episodes are predominant in the condition, treatment with lithium has the largest body of evidence[3],[6],[10]

. It has also been shown to reduce the risk of attempted, and completed, suicides in patients with bipolar disorder[13]

. However, lithium is not an uncomplicated medication to take. It is contraindicated in Addison’s disease, hypothyroidism and cardiac disease. A number of pre-initiation tests are required, including renal, thyroid, cardiac tests and body mass index (BMI) measurements[3],[6]

, as well as continuous plasma monitoring every three to six months to ensure treatment is being utilised within its narrow therapeutic and toxic range[2],[6]

. There are three preparations of lithium — Liskonum, Camcolit, and Priadel — which are not bioequivalent and for that reason patients should be advised to continue with the same brand once started. Any brand or formulation switches in hospital should take into account the different lithium salt contents of each product. Lithium toxicity can occur with the use of concomitant medications, as well as from dehydration or by reducing salt intake in the diet. In particular, concurrent use of diuretics can cause toxicity and specifically thiazide diuretics should be avoided. Other medicines that interact with lithium are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), although these may be less of a risk if taken regularly rather than on an as required basis[2]

. In 2015, a long-term study demonstrated an increased risk of end-stage renal disease, hypothyroidism and hypercalcaemia with continued lithium treatment[14]

.

Lithium is also teratogenic and carries a one in ten chance of congenital malformations[15]

. It is associated with a higher risk of miscarriage and cardiac abnormalities if taken during pregnancy[16]

. Some of these risks may be reduced by avoiding lithium during conception and the first trimester of pregnancy, and also by close monitoring[15]

. However, these risks need to be balanced against the high risk of relapse and the harm associated with this that could affect both mother and baby[10]

. Stopping and starting lithium may worsen disease progression[17]

,[18]

so it is most suitable for patients who are willing, and able, to take it on a long-term basis. The long-term outcomes of lithium use are controversial: some researchers believe it to be an underused and life-changing treatment[19]

while there is growing evidence that continued use is associated with progressive renal impairment[14]

, which may limit its usefulness.

A purple booklet produced by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) should be given to each patient starting lithium. It contains important information about taking lithium, a lithium therapy record book for recording blood plasma levels, and a lithium alert card for patients to carry with them to show healthcare professionals. The booklet outlines reasons for taking lithium, what checks are required to ensure it is taken safely, how the dose is decided, and any side effects and signs of toxicity. This booklet replaced the white lithium cards that were previously issued to patients. Patients should be informed that taking lithium may cause them to feel thirsty and need to urinate more, and it may cause weight gain, which could be related to increased consumption of sugary drinks. It can also cause a metallic taste in the mouth and a fine tremor in the hands. If the lithium dose is too high, they may experience a pronounced tremor, gastric problems, muscle weakness, unsteadiness, blurred vision, confusion and slurring of words.

Recommendations suggest if lithium is ineffective, valproate can be added[6],[20]

. The BALANCE trial demonstrated that both lithium alone, or lithium plus valproate, had better outcomes than valproate monotherapy in preventing relapse[20]

. This contrasts with a recent Cochrane review that found neither treatment was favourable in efficacy in preventing relapse of bipolar disorder[21]

. It also found people taking valproate on a long-term basis were more likely to continue taking it than those taking lithium[21]

.

Valproate maintenance treatment

Initiation of valproate requires baseline full blood counts, liver function tests, and weight or BMI measurements, and these should be repeated at six months and then annually[6]

. Routine plasma monitoring is no longer recommended and indicated only if ineffectiveness, poor adherence or toxicity is suspected[6]

. The dose for initiating Depakote in mania is 750mg split in two to three doses a day, while a slightly higher dose is required for sodium valproate. Epilim Chrono (a prolonged-release formulation) can be taken once daily and may be better tolerated as lower peak plasma levels are produced compared with enteric-coated forms[2],[3]

. If prescribed for bipolar maintenance treatment, a lower starting dose of 500mg daily can be used and a plasma level of at least 50mg/L should be aimed for[3]

.

Common side effects experienced with valproate are nausea, gastric problems, tremor, anaemia, hair loss with curly regrowth, weight gain and confusion. Valproate is contraindicated in hepatic disease and porphyria, and special warnings are given in summaries of product characteristics (SPCs) relating to liver damage and use in pregnancy[22]

. Patients and carers should be warned to look out for signs of liver damage, such as jaundice, tiredness, weight loss and oedema, and should be told about the need for liver function monitoring.

In general, valproate is not recommended for use in women of childbearing age. The SPC for semi-sodium valproate states: “Depakote should not be used in female children, in female adolescents, in women of childbearing potential, and pregnant women, unless alternative treatments are ineffective or not tolerated because of its high teratogenic potential and risk of developmental disorders in infants exposed in utero to valproate. The benefit and risk should be carefully reconsidered at regular treatment reviews, at puberty, and urgently when a woman of childbearing potential treated with Depakote plans a pregnancy, or if she becomes pregnant”[22]

. NICE guidance also states that valproate should not be routinely offered to women of childbearing potential for long-term treatment or to treat an acute episode[6]

. These guidelines and the warnings described in the MHRA’s patient information booklet[1]

go on to state that any valproate initiation should be undertaken by a specialist in epilepsy or bipolar disorder. The guidance indicates that for some women with either epilepsy or bipolar disorder, only valproate is effective or tolerable and, therefore, there are circumstances when valproate will be taken on a long-term basis despite safety warnings.

For women with either condition who need to take valproate, all risks should be fully discussed. The importance of using contraception should be highlighted, treatment should be regularly reviewed, and any thoughts about pregnancy should be deliberated and planned in advance. As a significant proportion of pregnancies are unplanned in adolescents with bipolar disorder[23]

, it is important for the risks to be outlined before initiation and to reinforce to the patient that she should immediately contact the prescriber if she becomes pregnant unexpectedly.

In addition to the risks outlined by the MHRA in the patient booklet, healthcare professionals were also sent a letter at the beginning of 2015 highlighting the risks associated with valproate products and the risk of abnormal pregnancy outcomes. As well as congenital malformations, this letter describes studies in which 30–40% of preschool children exposed to valproate in utero have delayed early development relating to walking, talking, IQ scores, language and memory, as well as increased risks of being diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)[24]

.

For women who are taking valproate and become pregnant, consideration should be given to stopping treatment or switching to alternative treatments. Stopping may only be a viable option if the woman is currently well and the risk of relapse is deemed low. Switching treatment also means the foetus will be exposed to more medications. If valproate is to be continued, the lowest possible effective dose should be used, and either a controlled-release form should be prescribed or small doses taken throughout the day to avoid high peak levels.

Folic acid deficiency is known to occur during pregnancy. The use of folic acid 400µg to 5mg daily is advised for all women planning pregnancy to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (see ‘Box 2: Neural tube defects’ for more information on folic acid supplementation and doses) and current advice recommends that it is taken alongside valproate. However, recent studies have questioned the mechanism of action and whether folic acid actually reduces defects[25]

,[26],[27]

. Individual case studies have shown it not to be protective against malformation or birth defects[28]

. Nevertheless, based on past research and World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, no harm is caused by folate therapy, and as the benefits may be significant, it is sensible to continue folic acid supplementation until more is known.

Box 2: Neural tube defects

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are serious congenital malformations of the brain and spine. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 300,000 NTDs each year[29]

. The two most common NTDs are spina bifida (affecting the spine) and anencephaly (affecting the brain). These occur early in pregnancy between the 20th and 28th day after conception when the neural tube, which becomes the spine and brain, does not close properly. Spina bifida can cause mild to severe lifelong disabilities and babies with anencephaly almost always die shortly after birth[29]

. The exact cause is unknown and 95% of women who have babies with NTDs have no family history of the condition[30]

.

Folic acid is a vitamin belonging to the B complex group that plays an essential role in cell division. In the early part of development, the unborn child requires higher levels of folic acid to grow cells, tissues and organs[30]

. Since 1980, it has been shown that the addition of 400µg of folic acid before and at the start of pregnancy significantly reduces the number of NTDs[29]

. Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, it has been suggested that methionine synthase could be involved. Methionine synthase transforms homocysteine into methionine using a methyl group provided by the co-enzyme folic acid. If this reaction does not take place on account of a lack of folic acid, homocysteine levels rise and this appears to prevent the neural tube closing[29]

.

The dose of folic acid for women at low risk of conceiving a child with NTDs is 400µg daily, ideally started a month before conception and continuing until week 12 of pregnancy. If pregnancy is unplanned, folic acid should be started as soon a pregnancy is suspected and continued until week 12. For couples at higher risk of conceiving a child with a NTD (i.e. if there is a family history, a previous pregnancy affected by a NTD, if the mother has coeliac disease, diabetes mellitus, sickle-cell anaemia, or is taking antiepileptic medication, or who may be at risk of unplanned pregnancy), folic acid 5mg daily is advised, continuing until week 12 of pregnancy (unless the woman has sickle-cell anaemia)[2]

. Although high levels of folic acid are found in various vegetables and in some fruit there is not enough content even in a folic acid-rich diet to obtain enough folic acid, so vitamin supplementation is necessary. Countries including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ghana, South Africa, Jordan, Saudia Arabia and Qatar have mandatory fortification of foods with folic acid, such as flour and cereals[29],[30]

.

Carbamazepine maintenance treatment

An alternative antiepileptic that can be used in bipolar disorder is carbamazepine, which is licensed for focal and secondary generalised tonic-clonic seizures, primary generalised tonic-clonic seizures, trigeminal neuralgia and for prophylaxis of bipolar disorder that is unresponsive to lithium[2]

. It is contraindicated in individuals with atrioventricular block, a history of bone marrow depression, or a history of hepatic porphyrias[31]

. The starting dose is 400mg, increasing until symptoms are controlled or a maximum dose of 1.6g a day in divided doses is reached. The usual range is 400–600mg daily with plasma levels of between 7–12mg/l[3]

. Common side effects of carbamazepine are dizziness, drowsiness, ataxia, diplopia, headache, nausea, vomiting, urticaria, altered liver function and blood disorders. Warnings in the SPC that should be highlighted to patients are signs of agranulocytosis, which may occur occasionally to frequently, and serious skin reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Patients and carers should also be warned to look out for symptoms of fever, sore throat, rash, ulcers in the mouth, bruising or the appearance of red or purple spots. Any of these should be reported to the prescriber immediately[31]

. Pre-initiation tests should include full blood counts with urea and electrolytes and liver function tests, and baseline weight measurements.

Carbamazepine is available in several formulations on account of its use in epilepsy: standard tablets, chewable tablets, prolonged-release tablets, liquid formulations and suppositories. It is recommended that patients are maintained on a specific manufacturer’s brand when carbamazepine is used for epilepsy but this does not apply when using it for mood stabilisation or neuralgia[2]

. The modified-release forms, which can be given once or twice daily, are associated with fewer side effects because high peak levels are avoided[3]

.

Carbamazepine is metabolised by cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4 and it is also a potent inducer of this enzyme; therefore, it causes significant drug interactions. Co-administration with several antidepressants, antiepileptics and antipsychotics, as well as antivirals, anticoagulants, calcium-channel blockers, methadone, theophylline, levothyroxine, corticosteroids and oestrogens, will result in lower levels of these medications leading to reduced efficacy or no activity. Women taking oral contraceptives should be prescribed products containing 50µg or more of oestrogen, or should be advised to use a non-hormonal method of contraceptive. Interactions with some antibiotics, some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) antidepressants, olanzapine, azole antifungals, diltiazem, verapamil and cimetidine cause higher carbamazepine levels, which are associated with increased adverse events (see the BNF for a full list of interactions or individual SPCs for further information on interaction and specific advice relating to whether medication should be avoided or any necessary dose changes). Another significant contraindication involves the use of clozapine, which also causes agranulocytosis. The use of the two products together should always be avoided.

Carbamazepine has a known association with congenital malformations and developmental disorders[31],[32]

. The frequency of adverse events when carbamazepine was used during pregnancy was given as 8.2% in one study[33]

, although a more recent systematic review of studies concluded the risk to be specific to spina bifida, and an association with other malformations, such as cleft palate, was not confirmed[34]

. General advice for women taking carbamazepine is similar to that with valproate: inform them of the risks, discuss effective non-hormonal contraception, plan the pregnancy in advance, take folic acid supplementation, avoid all antiepileptics if it is safe to do so (if not, use monotherapy with the lowest possible dose) and, additionally, give vitamin K1 to the mother in the final weeks of pregnancy and 1mg parenterally to the neonate after delivery[31],[35]

.

Evidence for the use of carbamazepine for maintenance treatment was demonstrated against placebo in a 2005 study, which used the extended-release capsule formulation[36]

. Studies comparing carbamazepine with lithium show superiority for lithium in the treatment of bipolar I disorder, but in patients with other types of bipolar disorder or comorbidities some benefits with carbamazepine were shown[37]

. In treatment-naïve patients, carbamazepine also appears to be better tolerated and have slightly lower rates of trial withdrawal[38]

. In contrast, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials demonstrated comparable efficacy with carbamazepine and lithium but fewer trial dropouts with lithium[39]

.

Most comparisons of valproate and carbamazepine relate to the treatment of mania but a literature review of maintenance treatment suggests valproate is better tolerated for short-term use and carbamazepine is better suited for long-term therapy[40]

.

Lamotrigine maintenance therapy

The use of lamotrigine to treat bipolar depression and initiation of this medication has been discussed earlier in this article. It is a useful maintenance treatment as it is licensed for prophylaxis, does not induce switching to mania or rapid cycling, and causes less weight gain than lithium[3]

. Lamotrigine may be a safer alternative in pregnancy with studies finding lower rates of foetal malformation when used in women with epilepsy compared with valproate[41],[42]

.

Antipsychotic maintenance therapy

An alternative to lithium and antiepileptics is to use antipsychotics. This may be particularly useful when they have been used in an acute manic episode and can be continued as preventative treatment. Antipsychotics have a variety of actions that can be useful in bipolar disorder: antimanic, anxiolytic, antidepressant, mood-stabilising and sedative[3]

. Olanzapine and quetiapine are both licensed for preventing recurrence in bipolar disorder and for treating mania. The doses are generally lower for prophylaxis than for manic phases: the dose of olanzapine should be about 10mg a day (range of 5–20mg) and the quetiapine dose should usually be about 300mg once daily (range 300–800mg)[2]

.

When initiating antipsychotics, a patient’s pulse, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c, blood lipid profile and BMI should be measured. An electrocardiogram and measurement of prolactin levels may also be recommended[3],[6]

. It is then advised that pulse and blood pressure readings are taken after each dose change, and BMI, blood glucose levels and blood lipid levels should be monitored every three months for at least the first year[6]

. Common side effects of olanzapine are drowsiness, weight gain, low blood pressure, constipation, dry mouth and increased lipid levels[43]

. Common quetiapine side effects are low blood pressure, dizziness, drowsiness, tachycardia, weight gain and constipation[44]

.

The efficacy of olanzapine as prophylaxis is demonstrated in a randomised placebo controlled trial where olanzapine delayed relapse by a median of 174 days compared with 22 days for placebo[45]

. When olanzapine was compared with lithium, olanzapine was more effective than lithium in preventing manic and mixed episode relapse but both were comparable in preventing depressive relapse[46]

.

Most evidence for quetiapine relates to its use in bipolar depression but one small-scale study considered quetiapine monotherapy in prophylaxis. This study reported a significant improvement in scores using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Clinical Global Impressions (CGI), and Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAM-D), with no significant side effects and good compliance[47]

. Another study considers quetiapine a true mood stabiliser in the sense that it has the ability to treat all phases of bipolar disorder and there is evidence for its usefulness in long-term prevention[48]

.

NICE recommends antipsychotics in pregnancy when a pharmacological treatment is indicated for prophylaxis, lithium is being stopped, the patient develops mania, or the patient is planning to breastfeed[49]

. The risks of antipsychotic use in pregnancy are classified by the FDA according to an ABCDX system of evidence knowledge. Category A contains drugs in which adequate and well-controlled drug trials have failed to show a risk to the foetus in the first trimester of pregnancy (folic acid falls into this group). Category X contains drugs where studies or experience have demonstrated adverse effects and risks that outweigh the benefits of the drugs (methotrexate and finasteride fall into this group). Most atypical antipsychotics fall into category C where animal studies have shown an adverse effect on the foetus but there are no adequate well-controlled studies in women, and potential benefits may outweigh the risks. The studies that do exist display, in some cases, an increased risk of congenital malformations, gestational diabetes, and an increased risk of caesarean deliveries[50]

, while in others, no association of major malformations is reported[51]

.

Conclusions

The risk of malformation in the general population is 2–4%, increasing with age[10]

. Therefore, no pregnancy is without risk and the specific risk associated with antipsychotics is not well established. Antidepressants, antiepileptics and antipsychotics all have risks and require monitoring in patients with BPAD. In pregnancy, antipsychotics appear to have fewer risks than antiepileptics, although lamotrigine appears to be comparatively safe with regard to foetal malformations from information reported in the UK register data[52]

. Polypharmacy with antiepileptics also presents an increased risk of malformations[3],[52]

. These risks should be considered against the risk of bipolar relapse. Untreated or subtherapeutic treatment may be more dangerous to both mother and baby.

Valproate exhibits the greatest risks and should be avoided where possible. However, valproate should not be restricted without individual factors being considered (i.e. although a woman is of childbearing age, is she, in reality, likely to become pregnant?). If valproate is prescribed in any of its forms, for any indication, the information highlighted by the MHRA should be given to any female patient before starting treatment.

Any treatment that achieves fast remission of bipolar depression or mania can be considered a favourable medication for long-term monotherapy[10]

.

Neelam Sharma is a registered pharmacy technician in the UK. Correspondence to: neelam.sharma2@uclh.nhs.uk

Author disclosure and conflicts of interest disclosure: The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Medicines related to valproate: risk of abnormal pregnancy outcomes. Available at: www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/ (accessed April 2016).

[2] British National Formulary 69. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2015.

[3] Taylor D, Paton C & Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry 12th Edition. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

[4] Redfield Jamison K. An unquiet mind: a memoir of moods and madness. London: Picador; 1996.

[5] Ghaemi N, Boiman E & Goodwin F. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2000;61:804–808. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1013

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. Clinical guidance (CG185) 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[7] Geddes JR & Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. The Lancet 2013;9878:1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60857-0

[8] Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Macfadden W et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1351–1360. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351

[9] GlaxoSmithKline. Summary of product characteristics. Lamictal. 2015. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[10] Goodwin GM. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition — recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2009;23:346–388. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102919

[11] Lundbeck Limited. Summary of product characteristics. Sycrest. 2015. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[12] Bowden CL, Göğüş A, Grunze H et al. A 12-week, open, randomized trial comparing sodium valproate to lithium in patients with bipolar I disorder suffering from a manic episode. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;23:254–262. doi: 10.1097/yic.0b013e3282fd827c

[13] Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P et al. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta analytic review. Bipolar Disorder 2006;8:625–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00344.x

[14] Shine B, McKnight RF, Leaver L et al. Long-term effects of lithium on renal, thyroid, and parathyroid function: a retrospective analysis of laboratory data. The Lancet 2015;9992:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61842-0

[15] Williams K & Oke S. Lithium and pregnancy. BJPsych Bulletin 2000;24:229–231. doi: 10.1192/pb.24.6.229

[16] Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Tahover E et al. Pregnancy outcome following in utero exposure to lithium: a prospective, comparative, observational study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2014;171:785–794. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.12111402

[17] Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L & Viguera AC. Discontinuing lithium maintenance treatment in bipolar disorders: risks and implications. Bipolar Disord 1999;1:17–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.1999.10106.x

[18] Cavanagh J, Smyth R & Goodwin GM. Relapse into mania or depression following lithium discontinuation: a 7-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2004;109:91–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00274.x

[19] Malhi GS, Tanious M, Bargh D et al. Safe and effective use of lithium. Australian Prescriber 2013;36:18–21. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2013.008

[20] The BALANCE investigators and collaborators. Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder (BALANCE): a randomised open-label trial. The Lancet 2010:375:385–395. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102919

[21] Cipriani A, Reid K, Young AH et al. Valproate for keeping people with bipolar disorder well, after mood episodes. Cochrane database 2013. PMID: 24132760

[22] Sanofi. Summary of product characteristics. Depakote. 2009. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[23] Heffner JL, DelBello MP, Fleck DE et al. Unplanned pregnancies in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:1319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12060828

[24] Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Medicines related to valproate: risk of abnormal pregnancy outcomes. Guide for healthcare professionals. 2015. Available at: www.gov.uk (accessed April 2016).

[25] Morrow JI, Hunt SJ, Russell AJ et al. Folic acid use and major congenital malformations in offspring of women with epilepsy: a prospective study from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:506–511. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.156109

[26] Denny KJ, Jeanes A, Fathe K et al. Neural tube defects, folate, and immune modulation. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology 2013;97:602–609. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23177

[27] Eadie MJ & Vajda FJ. Should valproate be taken during pregnancy? Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2005;1:21–26. PMCID: PMC1661607

[28] Duncan S, Mercho S, Lopes-Cendes I et al. Repeated neural tube defects and valproate monotherapy suggest a pharmacogenetic abnormality. Epilepsia 2001;42:750–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.44300.x

[29] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Folic acid recommendations. 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/index.html (accessed April 2016).

[30] Jaquier M. Prevention of anencephaly. 2015. Available at: www.anencephalie-info.org/e/prevention.php (accessed April 2016).

[31] Novartis. Summary of product characteristics. Tegretol prolonged release tablets. 2015. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[32] Holmes LB, Harvey EA, Coull BA et al. The teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1132–1138. doi: 10.1056/nejm200104123441504

[33] Meador KG, Baker GA, Finnell RH et al. In utero antiepileptic drug exposure — Fetal death and malformations. Neurology 2006; 67:407–412. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227919.81208.b2

[34] Jentink J, Loane MA, Morris JK et al. Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital malformations: systematic review and case-control study. The BMJ 2010;341:c6581. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6581

[35] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Epilepsies: diagnosis and management. NICE guidance (CG137). 2012. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137 (accessed April 2016).

[36] Weisler RH, Keck PE, Swann AC et al. Extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for acute mania in bipolar disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2005;66:323–330. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0308

[37] Greil W, Kleindienst N, Erazo N et al. Differential response to lithium and carbamazepine in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 1998;18:455–460. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199812000-00007

[38] Hartong EGTM, Moleman P, Hoogduin CAL et al. Prophylactic efficacy of lithium versus carbamazepine in treatment-naive bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:144–151. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0206

[39] Ceron-Litvoc D, Soares BG, Geddes J et al. Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Psychopharmacol 2009;24:19–28. doi: 10.1002/hup.990

[40] Nasrallah HA, Ketter TA & Kalali AH. Carbamazepine and valproate for the treatment of bipolar disorder: a review of literature. Journal of Affective Disorders 2006;95:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.030

[41] Vajda FJE, O’Brien TJ, Lander CM et al . The teratogenicity of the newer antiepileptic drugs – an update. Acta Neurol Scand 2014;130:234– 238. doi: 10.1111/ane.12280

[42] Newport DJ, Stowe ZN, Viguera AC et al. Lamotrigine in bipolar disorder: efficacy during pregnancy. Bipolar Disord 2008;10:432–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00565.x

[43] Eli Lilly and Company. Summary of product characteristics. Zyprexa. 2014. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[44] AstraZeneca UK Limited. Summary of product characteristics. Seroquel. 2015. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[45] Tohen M, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine as maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder responding to acute treatment with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:247–256. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.247

[46] Tohen M, Greil W, Calabrese JR et al. Olanzapine versus lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: A 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1281–1290. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1281

[47] Altamura AC, Salvadori D, Madaro D et al. Efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder: preliminary evidence from a 12-month open label study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2003;76:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00075-7

[48] Vieta E. Mood stabilization in the treatment of bipolar disorder: focus on quetiapine. Human Psychomacology: Clinical and Experimental 2005. doi: 10.1002/hup.689

[49] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. NICE guidelines (CG192) 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk (accessed April 2016).

[50] Reis M & Kallen B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2008;28:279–288. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e318172b8d5

[51] McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study.J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:444–449. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0406

[52] Eadie MJ. Antiepileptic drug safety in pregnancy: possible dangers for the pregnant woman and her foetus. Clinical Pharmacist 8:1. doi: 10.1211/cp.2016.20200320