Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Know the different frailty syndromes and their risk factors;

- Know how to identify frailty and how levels of frailty might impact care;

- Understand how the pharmacy team can contribute to the care of patients living with frailty.

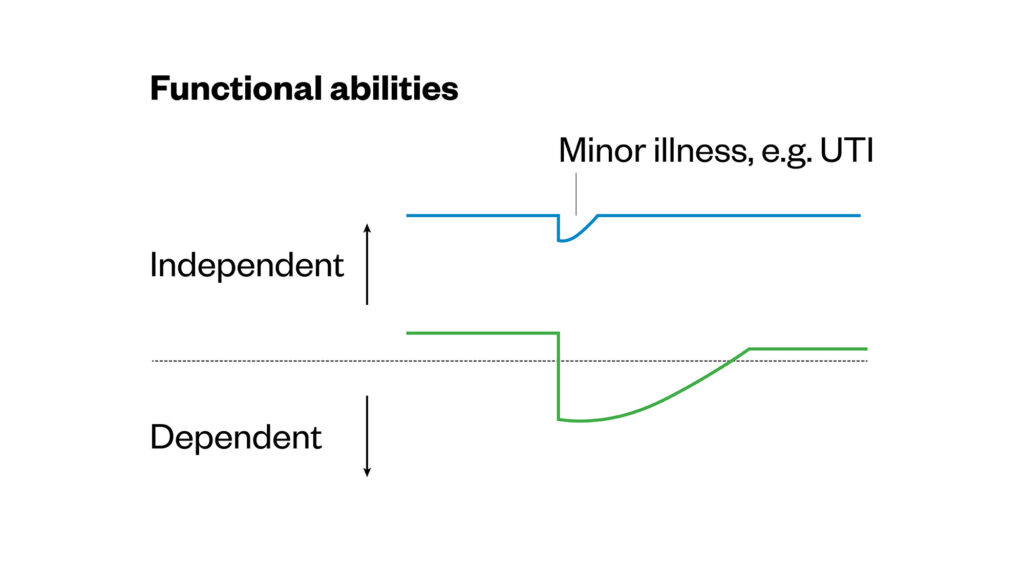

Frailty is a distinctive health state related to the ageing process where multiple body systems gradually lose built-in reserves1,2. Both the number of older people living with multiple long-term conditions and those living with frailty is increasing3,4. When someone who has frailty is challenged by a minor event, it can lead to potentially serious adverse outcomes. They can take longer to recover than those who are not frail and often do not return to their previous level of function (see Figure 1)5,6.

Figure 1: Susceptibility of frail older adults to an unexpected change in health function following a minor illness (e.g. UTI)6

Reproduced with permission

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Minor stressors might include infection (e.g. UTI), a trip to A&E after a fall or even a trial of a new medication, such as an analgesic. These can have unforeseen and adverse outcomes (e.g. falls, hospital admission and increase risk of death) that can significantly affect quality of life for those who are frail6,7. Frailty is not an inevitable part of ageing; around 10% of people in the UK aged over 65 years are living with frailty and this increases to between 25–50% of those over the age of 85 years6,8. It is important to acknowledge that frailty is not static — it can be improved or made worse. Understanding an individual’s level of frailty can help healthcare professionals make better informed choices when addressing their underlying conditions.

Frailty syndromes

There are two broad models of frailty, the first of which is known as the ‘phenotype’ model3. This describes a group of patient characteristics that include unintentional weight loss, reduced muscle strength, reduced gait speed, self-reported exhaustion and low energy expenditure. Individuals with three or more of these characteristics are considered to be frail3.

The second model of frailty is known as the ‘cumulative deficit’ model, which is broader than the phenotype model and encompasses comorbidity, disability, cognitive, psychological and social factors9,10.

A central feature of physical frailty as defined by the ‘phenotype’ model is loss of skeletal muscle function, known as sarcopenia. There is a growing body of evidence documenting the major causes of this process, the strongest risk factor being age1. When frail patients have an acute admission to hospital, deconditioning can happen within hours. Data suggest that bed rest in the first 24 hours reduces muscle power and circulatory volume by up to 5%11. Up to 65% of older patients (aged over 65 years) experience decline in function during a hospital stay and research suggests that every ten days in hospital can lead to the equivalent of ten years ageing in the muscle of people aged over 80 years12. A hospital stay can also result in some patients prematurely requiring long-term care owing to deconditioning and the loss of functional abilities13.

There are five main symptoms to look out for that may indicate the person concerned is living with frailty:

- Falls — the patient may be described as presenting with collapse, their legs giving way or ‘found lying on floor’;

- Immobility — the patient presents with a sudden change in mobility or stability;

- Delirium — the patient presents with acute confusion, feeling ‘muddled’ or a sudden worsening of confusion in someone with known dementia;

- Incontinence — the patient presents with new onset or worsening of urine or faecal incontinence;

- Side effects — the patient shows susceptibility to side effects of medication (e.g. confusion when taking oxybutynin or postural hypotension when taking tamsulosin)14.

Identifying frailty

There are several tools to identify people living with frailty. These can be divided into two categories: individual assessments and population level assessments. Individual assessments include reactive assessment of function in the community and individual assessments of frailty on admission to hospital. Planned population level assessments use existing data to allow organisations to understand population level needs and enable them to proactively plan services at scale15.

There is a guide from Healthcare Improvement Scotland detailing the many different frailty tools that exist, the benefits of each and in what setting they may be useful15.

An example of a population-level assessment tool used in the community is the Electronic Frailty Index (eFI), which can be used to identify people as they progress through different levels of frailty16. As individuals interact with their GP practice, their records accumulate a list of read codes and community prescriptions. The EFI uses a subset of these codes to interpret up to 36 potential deficits (e.g. arthritis, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, memory and cognitive problems, falls, heart failure)16. The number of deficits that an individual is considered to have is then divided by the total of 36 to produce a score. This clinician validated score determines whether a person is considered fit, mildly frail, moderately frail or severely frail and nearing the end of life17.

The most commonly used tool for assessing frailty in the NHS is the Rookwood Clinical Frailty Scale from the Canadian Study of Ageing (see Figure 2)18. This was initially designed to summarise the results of a comprehensive geriatric assessment, but it is now used as a triage tool to help direct care. This judgement-based tool has nine levels ranging from 1 (‘very fit’) to 9 (terminally ill)19. There is a training module available via the Dalhousie website, as well as an app, to make it easier to use the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale with patients20,21. The scale is only validated in those aged over 65 years and is not validated in individuals with learning disabilities.

Levels of frailty

The eFI divides frailty into three levels: mild, moderate and severe16. NHS Scotland data using the eFI show that around 35% of people in Scotland aged over 65 years are living with mild frailty, 15% are living with moderate frailty and 5% are living with severe frailty8. As the level of frailty increases so does the risk of harm, such as hospital admission and mortality3,16. Patients with higher levels of frailty have an increased use of unscheduled care, such as in A&E, out-of-hours care or walk-in centres, with an increase in unplanned admissions and the number of contacts with primary care teams (see Table 1)8. Data also show that the more frail an individual is, the increased likelihood of them being prescribed more medicines, which can increase inappropriate polypharmacy, as well as prescribing costs8. It is now recognised that services should be built around the needs of frail patients to minimise harm and improve clinical effectiveness4.

Interventions

Interventions to reduce the risk of harm may vary depending on the level of frailty: in mild frailty, the focus is around preventative and proactive care; moderate frailty can be targeted at population level for polypharmacy review; and the focus in severe frailty may be a supportive care approach that includes future care planning8. For more information, see ‘Polypharmacy and deprescribing in older people’.

Older age, being a resident in long-term care facility and taking multiple medications are factors that carry an increased risk of frailty22.

The following interventions may help to improve the level of frailty or prevent frailty:

- The evidence for the role of diet in frailty is not extensive, but sub-optimal protein and total calorie intake and vitamin D insufficiency have been implicated. Addressing these factors could improve symptoms of frailty;

- The most studied modifiable influence of frailty is physical activity, particularly resistance exercise, which is beneficial for preventing and treating the functional performance component of frailty;

- Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is the gold standard for frailty management in older people. It involves a holistic, interdisciplinary assessment of an individual. Patients receiving CGA are 12 times more likely to be alive and living at home 6 months after intervention;

- The British Geriatric Society recommends that medication review is a crucial component of the CGA and that judicious review of medicines, their indications, side effects and benefits can cause significant and rapid improvement in a patient’s condition;

- Signposting community services (e.g. Age UK, social prescribing, Citizens Advice)1,22.

Falls and polypharmacy

There is evidence around the many benefits of polypharmacy reviews; these include reducing drug burden, reducing medicine-related harms, increasing medicines appropriateness, as well as substantial cost savings (see ‘Polypharmacy and deprescribing in older people’23).

Polypharmacy and certain medicines that can cause sedation, lower blood pressure (BP) or lower blood sugar can significantly increase the risk of falls, with one analysis estimating a 75% increase in risk for patients taking four or more medications24. One in five people aged over 65 years living in the community report having had a fall in the past year, with a higher prevalence among older adults aged over 80 years; those residing in a care home setting are three times more likely to fall than those living in their own home24,25. Falls are one of the most common reasons for hospital admission in individuals aged over 65 years and are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality; up to 30% of patients with hip fracture will die within one year of fracture25. At the point of admission, the guidelines suggest a holistic multifactorial falls risk assessment should be carried out, which should include a medication review to identify any falls risk increasing drugs (FRIDs) and that deprescribing should be considered where appropriate26,27.

There are tools available to help identify these medicines and aid decision making in deprescribing, such as the STOPP Falls and the NPFPG/RPS Medicines and Falls26,27. It is recommended that a lying or sitting and standing BP is checked, particularly for those on medicines that can cause postural drop and that pain and urinary incontinence should be assessed, as both are risk factors for falling27.

The evidence of benefit of BP control to prevent cardiovascular events is not as strong for those living with moderate-to-severe frailty and single drug therapy may be appropriate to control BP28. Therefore, the risk of using medicines to treat BP control may outweigh the benefits in people with moderate to severe frailty.

BP-lowering treatment should only be considered from ≥140/90 mmHg among persons meeting the following criteria:

- Pre-treatment symptomatic orthostatic hypotension;

- Age ≥85 years;

- Clinically significant moderate-to-severe frailty;

- Limited predicted lifespan (<3 years)28.

Case studies

Case 1: Primary care setting

A 76-year-old female with moderate frailty (Rockwood Score 6) presents to her GP because she has been unsteady on her feet and more confused in the past two weeks. The patient lives at home with her husband and receives help from family. It is noted that she is taking a lot of different medicines and may benefit from a review with the practice pharmacist, who is an independent prescriber, utilising a person-centred structured medication review, see ‘Polypharmacy and deprescribing in older people’.

Consultation

The patient has a history of urinary incontinence, osteoporosis, hypertension, TIA and osteoarthritis. She has been feeling a bit confused in the past few weeks, it is noted that she has good oral intake and no signs of acute infection. The patient has occasional constipation and mild ankle oedema.

The following physical assessments are made: BP 110/64 with no postural drop, temperature 36.8°C, oxygen saturation 98%, bloods normal. The patient currently takes the following medications:

- Accrete D3 One-A-Day 1 tablet, once daily;

- Alendronic acid 70mg, once weekly;

- Amitriptyline 25mg, once daily at night;

- Atorvastatin 40mg, once daily at night;

- Clopidogrel 75mg, once daily;

- Lactulose 15mL, twice daily;

- Omeprazole 20mg, once daily;

- Solifenacin 5mg, once daily (recently commenced);

- Co-codamol 30/500mg, two tablets four to six-hourly, as required;

- Clinitas carbomer 0.2% eye gel prn for dry eyes.

A CGA and a polypharmacy review is carried out as part of the MDT assessments with the patient, the observations from both can be seen in Table 225.

The patient is also advised on the following lifestyle modifications to manage her incontinence: reducing caffeine intake, consider reducing salt intake, consider reducing fluid intake, weight loss if body mass index is ≥30kg/m² and smoking cessation if appropriate.

Outcome and monitoring

Following the reduction in the patient’s medication burden, she reports improved quality of life, feeling brighter, less confused, less constipated and has improved mobility. The patient’s ACB has been reduced from 7 to 1. Any medication changes are explained, and advice is given on what to do if symptoms returned. This can be done verbally and written information may also be provided. A suitable time for follow-up is also agreed with the patient.

Case 2: Acute care setting

A 90-year-old male with mild frailty (Rockwood Score 4) presents to A&E with pain and bruising in the right chest below axilla, lateral ribs. The patient tripped while doing gardening and also sustained a superficial facial injury.

The patient lives with his wife and is usually independent with activities of daily living, such as household chores and gardening. There are no concerns with cognition and he manages his own medicines. He walks with a stick and still drives.

Observations (during admission)

The patient weighs 56kg. His head CT is normal. A CT of his thorax reveals:

- Fractures of the posterior and lateral right 5th–8th ribs;

- Right hydropneumothorax;

- Chest drain inserted in resus.

The patients past medical history can be seen in Box 1.

Box 1: Patient past medical history

- Right thyroid mass undergoing investigations. Right maxillary sinus heterogenous mass found incidentally in computed tomography of the head this week (possible malignancy);

- Left cheek squamous cell carcinoma, excised;

- Mitral valve & tricuspid valve repair;

- Coronary artery bypass graft;

- Atrial fibrillation;

- Heart failure (pro-B-type natriuretic peptide 2592);

- Hypertension;

- Chronic urinary retention.

The pharmacist completes the drug history on the short-stay medical admissions ward, the patient currently takes:

- Apixaban 2.5mg, twice daily;

- Bumetanide 2.0mg, twice daily;

- Bisoprolol 2.5mg, once daily;

- Ramipril 2.5mg, once daily;

- Allopurinol 300mg, once daily;

- Amlodipine 5.0mg, once daily.

A CGA and a medication review is carried out as part of the MDT assessments with the patient, the observations from both can be seen in Table 3.

The patient is found to have orthostatic hypotension (OH), is defined as a fall in systolic BP of at least 20mmHg (at least 30mmHg in patients with hypertension) and/ or a fall of diastolic BP of at least 10mmHg within three minutes of standing. The incidence of OH increases with age and may be associated with the risk of falling.

Monitoring

There is the opportunity to monitor BP as an inpatient, but home monitoring is required and it will be reviewed by the patient’s GP surgery in four weeks.

Assessment of heart failure control will be included as part of the BP review. This includes monitoring symptoms of breathlessness, peripheral oedema, weight, exercise tolerance and use of pillows at night in bed.

Pain control will be monitored — the patient should only require short-term opioids to manage pain and it should be optimised to ensure it does not reduce mobility and increase risk of chest infection.

Outcome

The patient was reviewed in the GP surgery by the practice pharmacist following discharge from hospital. They have been taking bumetanide earlier in the day (same dose as pre-admission) and this has reduced nighttime waking to occasionally once at night.

His weight has not changed since discharge and his breathlessness has improved since discharge from hospital.

Lying and standing BP indicates no significant postural drop. Ramipril remains at lower dose and no need for amlodipine — BP remains 125/72.

The pharmacist discusses risk/benefits of low dose PPI to cover DOAC — patient felt he would wish to be on one — this is prescribed by the practice pharmacist and added to repeat prescription.

Five weeks following his fall, he remains on regular paracetamol but is only taking morphine liquid at night occasionally.

FRAX score is completed to evaluate fracture risk — the pharmacist notes that the patient’s age is at the upper limit of the tool validation. The FRAX score is amber (intermediate risk), in accordance with the NOGG guidelines it is recommended that a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is used to measure bone density — the patient is happy for this referral to be made.

The patient’s calcium dietary intake is checked using the Edinburgh University Calcium calculator and found to be adequate. The pharmacist recommends that the patient take low dose vitamin D (without calcium), which can be bought by the patient from their local supermarket.

Case 3: Care home setting

An 83-year-old female with severe frailty (Rockwood Score 7) has been bed-bound in a care home for the past two years. She is reviewed by the pharmacist as care home staff had noticed a recent deterioration; symptoms include weight loss, refusing meals/loss of appetite, tiredness, weakness, sedation and urinary incontinence. The patient’s past medical history can be seen in Box 2.

Box 2: Patient past medical history

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus;

- Constipation;

- Dry eyes;

- Vascular dementia; started on risperidone for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) two years ago;

- Pain.

Assessment and examination

The pharmacist assesses the patient and notes the following observations:

- BP 115/76 (unable to assess for postural drop as bed bound);

- CrCl 22mL/minute (CKD 4);

- Combined anticholinergic burden score (ACB) 3.

The pharmacist also takes the patients medication history and finds that the patient is currently prescribed the following medications:

- Risperidone 0.5mg, twice daily;

- Mirtazapine 45mg, once nightly;

- Diazepam 2mg, when required — not currently taking;

- Metformin 500mg, once daily;

- Atorvastatin 20mg, once nightly;

- Donepezil 10mg, daily;

- Laxido, twice daily;

- Paracetamol 1g, four times a day;

- Hypromellose eyedrops, when required;

- Prochlorperazine 5mg, when required for nausea.

Consultation

Given the patient’s multimorbidity and severe frailty, discontinuing medicines should be considered where risk outweighs benefit. The pharmacist carries out a CGA and a medication review with the patient, the observations from both can be seen in Table 429–31.

Monitoring and outcome

The patient should be reviewed by the pharmacist after any medicine changes. In severely frail patients, the care staff and LPA should be included in this review. The ongoing benefits and risks of individual medicines should be discussed and the care plan updated.

Following the CGA and medication review, the patient’s medication burden was reduced. There was a reduction in her ACB score and associated symptoms — the prescribing cascade was reduced. The patient reported being less drowsy, more engaged at mealtimes and gaining weight.

Best practice points

- The number of frail older patients is increasing, and recognising frailty syndromes and their risk factors is an important role of pharmacists in all sectors;

- Minor stressors can have a huge impact on frail patients, increasing the risk of morbidity and mortality;

- Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is the gold standard for frailty management and includes a comprehensive medication review;

- Falls are one of the commonest causes of hospital admissions in older people and many drugs can contribute to an increased risk of falls. Various tools, such as ‘StopFalls‘, can be used to help identify falls risk increasing drugs;

- Pharmacists play a major role in medicines optimisation in frail, older patients through structured medication reviews.

Related articles

This article is part of a series on frailty, for more information please see:

- 1.Fit for Frailty — Part 1: Recognition and management of frailty in individuals in community and outpatient settings. British Geriatrics Society. 2014. Accessed August 2025. https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018-05-14/fff2_short_0.pdf

- 2.Frailty – what it means and how to keep well over the winter months. NHS England. December 2013. Accessed August 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/ltc-op-eolc/older-people/frailty/

- 3.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56(3):M146-M157. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

- 4.Joining the dots: A blueprint for preventing and managing frailty in older people. British Geriatrics Society. 2023. Accessed August 2025. https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/attachment/2023-03-06/BGS%20Joining%20the%20Dots%20-%20A%20blueprint%20for%20preventing%20and%20managing%20frailty%20in%20older%20people.pdf

- 5.RightCare Pathway: Falls and Fragility Fractures. NHS England. 2017. Accessed August 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/rightcare/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/2017/12/falls-fragility-fractures-pathway-v18.pdf#:~:text=Commissioners%20responsible%20for%20Falls%20and

- 6.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9

- 7.Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. The Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1365-1375. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31786-6

- 8.Frailty and the electronic frailty index. Healthcare Improvement Scotland . 2019. Accessed August 2025. https://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.scot

- 9.Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10‐Year Outcomes of Frailty in Older Adults in Relation to Deficit Accumulation. J American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(4):681-687. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x

- 10.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty Defined by Deficit Accumulation and Geriatric Medicine Defined by Frailty. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2011;27(1):17-26. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.008

- 11.Panagioti M, Khan K, Keers RN, et al. Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. Published online July 17, 2019:l4185. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4185

- 12.Kortebein P, Symons TB, Ferrando A, et al. Functional Impact of 10 Days of Bed Rest in Healthy Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2008;63(10):1076-1081. doi:10.1093/gerona/63.10.1076

- 13.‘Sit Up, Get Dressed and Keep Moving!’ British Geriatrics Society. July 2020. Accessed August 2025. https://www.bgs.org.uk/‘sit-up-get-dressed-and-keep-moving’

- 14.Recognising frailty. British Geriatrics Society. June 2014. Accessed August 2025. https://www.bgs.org.uk/recognising-frailty

- 15.Frailty screening and assessment tools comparator. Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Accessed August 2025. https://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.scot

- 16.Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):353-360. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw039

- 17.Lansbury LN, Roberts HC, Clift E, Herklots A, Robinson N, Sayer AA. Use of the electronic Frailty Index to identify vulnerable patients: a pilot study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(664):e751-e756. doi:10.3399/bjgp17x693089

- 18.Rockwood K. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005;173(5):489-495. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050051

- 19.Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in Allocating Scarce Health Care Resources. Can Geri J. 2020;23(3):254-259. doi:10.5770/cgj.23.463

- 20.Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) Training Module. AIMS Research Group. Accessed August 2025. https://rise.articulate.com/share/deb4rT02lvONbq4AfcMNRUudcd6QMts3#/

- 21.Clinical Frailty Scale. NHS Specialised Clinical Frailty Network. Accessed August 2025. https://www.scfn.org.uk/clinical-frailty-scale

- 22.Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Toolkit for Primary Care Practitioners. British Geriatric Society. 2019. Accessed August 2025. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/resource-series/comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-toolkit-for-primary-care-practitioners#:~:text=The%20CGA%20toolkit%20for%20General

- 23.iSIMPATHY Evaluation Report. iSIMPATHY. 2023. Accessed August 2025. https://www.isimpathy.eu/uploads/iSIMPATHY_Evaluation_report_ver8_online.pdf#:~:text=The%20iSIMPATHY%20project%20embedded%20a

- 24.Medication and Falls. Deprescribing Network. Accessed August 2025. https://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/medications-and-falls

- 25.Managing Falls and Fractures in Care Homes for Older People – good practice resource. Care Inspectorate. 2011. Accessed August 2025. https://www.careinspectorate.com/images/documents/2737/2016/Falls-and-fractures-new-resource-low-res.pdf

- 26.Seppala LJ, Petrovic M, Ryg J, et al. STOPPFall (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk): a Delphi study by the EuGMS Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs. Age and Ageing. 2020;50(4):1189-1199. doi:10.1093/ageing/afaa249

- 27.Medicines and Falls. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2023. Accessed August 2025. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Pharmacy%20guide%20docs/Medicines%20and%20falls%209%2023%20%28RPSendorsed%29.pdf

- 28.Correction to: 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: Developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). European Heart Journal. 2025;46(14):1300-1300. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf031

- 29.Stopping antidepressants. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Accessed August 2025. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/mental-health/treatments-and-wellbeing/print-outs/stopping-antidepressants-information-resource-print-version-18-03-24.pdf?sfvrsn=76e4b9a8_3

- 30.Reducing Antipsychotic Prescribing in Dementia Toolkit. NHS PrescQIPP. 2014. Accessed August 2025. https://www.kmptformulary.nhs.uk/media/1042/prescqipp-reducing-antipsychotic-prescribing-in-dementia-toolkit.pdf

- 31.Decision aid: Antipsychotic medicines for treating agitation, aggression and distress in people living with dementia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018. Accessed August 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/antipsychotic-medicines-for-treating-agitation-aggression-and-distress-in-people-living-with-dementia-patient-decision-aid-pdf-4852697005