Shutterstock.com

Before reading this article, you should have read:

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand how religious or cultural beliefs and practices can affect diabetes management;

- Select the most appropriate management plan for an individual, keeping these cultural factors in mind.

Background

In the UK, the prevalence of diabetes in the South Asian population is up to six times higher than white people[1,2]. UK South Asian people with diabetes also have an increased risk of complications, such as coronary heart disease, diabetic retinopathy, and end-stage renal disease[3]. The UK South Asian population is not homogenous — different lifestyles have emerged as a result of migration patterns from different regions of South Asia over time. These cultural lifestyle practices depend on factors, such as ethnic, social, religious subgroups and migration history.

Religio-cultural practices are an integral component of daily life for faith communities and can affect health[4]. Fatalistic attitudes linked to religious beliefs about human destiny and fate can adversely affect the understanding of diabetes complications. This is a particular problem if people have poor glycaemic control but feel well, because they often wrongly perceive this as being in good health.

Diabetes care in a Hindu patient should consider the unique religious and cultural factors that affect management. Hindu food practices are influenced by religious scriptures and cultural texts, such as the Dharmasastra and the Manusmriti, which promote a diet that is harmonious with nature and respectful of all life forms[5]. For this reason, forms of vegetarianism are practised by many Hindus. Among those that do consume meat, beef is universally prohibited although dairy products — being perceived as gifts from sacred animals — may be permitted.

Fasting is not mandatory in Hinduism and is not governed by any formal rules but is often observed at various points throughout the year. Compared with other religions, Hinduism features more day or week-long fasting periods, although longer fasts also exist[6–8]. Similarly, feasting on certain food groups is also associated with festivals, such as sweets during Diwali. Food sharing also is important in Hindu culture, with consecrated vegetarian food and sweets distributed in temples, especially during festivals[4,9].

The overall heterogeneity of Hindu dietary practices makes the systematic study of the metabolic effects challenging. Similarly, variability through the population means that practices should never be assumed and need to be understood on an individual basis.

Clinicians must tailor management to the individual patient and ensure regimens are compatible with the patient’s religious practices.

Case presentation

‘Ms S’ is a 53-year-old South Asian woman of Hindu faith who lives in an inner city area. She was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus and started insulin two years ago.

Ms S has a strong family history of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. She has no micro or macro vascular changes. Her current medication regimen is metformin 500mg twice daily, linagiptin 5mg once daily, atorvastatin 40mg once daily, Humulin I 68 units at night.

Ms S’s daily routine revolves around the kitchen, cooking all meals for her extended family unit at home based on a very traditional South Asian diet. She also cooks at the temple for offerings and meetings. She eats three meals a day and eats food between meals at the temple.

Ms S has attended both a ‘Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed’ (DESMOND) programme and a locally delivered diet and lifestyle programme. She felt that the structured education programme was too generic to meet her requirements.

Ms S has very strong health beliefs around medication — feeling well while taking medicines is important to her. She has previously tried a sulphonylurea, an SGLT2 inhibitor and a glucagen-like peptide 1 receptor antagonist (GLP-1 RA), but stopped taking them soon after starting owing to side effects of nausea and diarrhoea. Ms S did not understand the benefits of these oral medicines and was not fully informed of the potential transient nature of side effects; however, she does not wish to try these again.

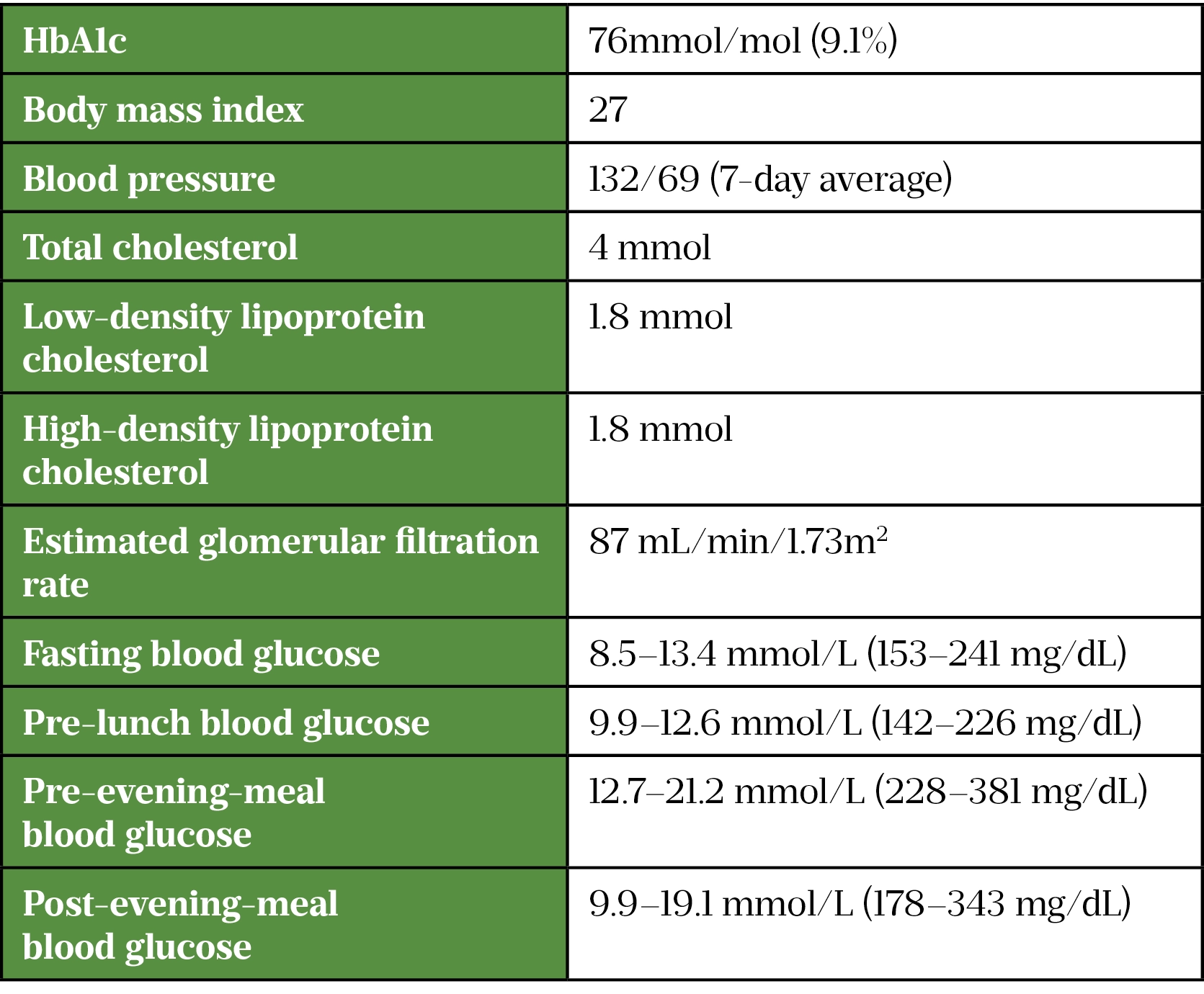

In recent months, there has been a discussion around a change to her insulin regimen for diabetes. Ms S is gaining weight, which she is aware increases cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance and is very anxious about the health consequences of prolonged poor control[10]. Her current health status is summarised in Table 1.

Clinical problems

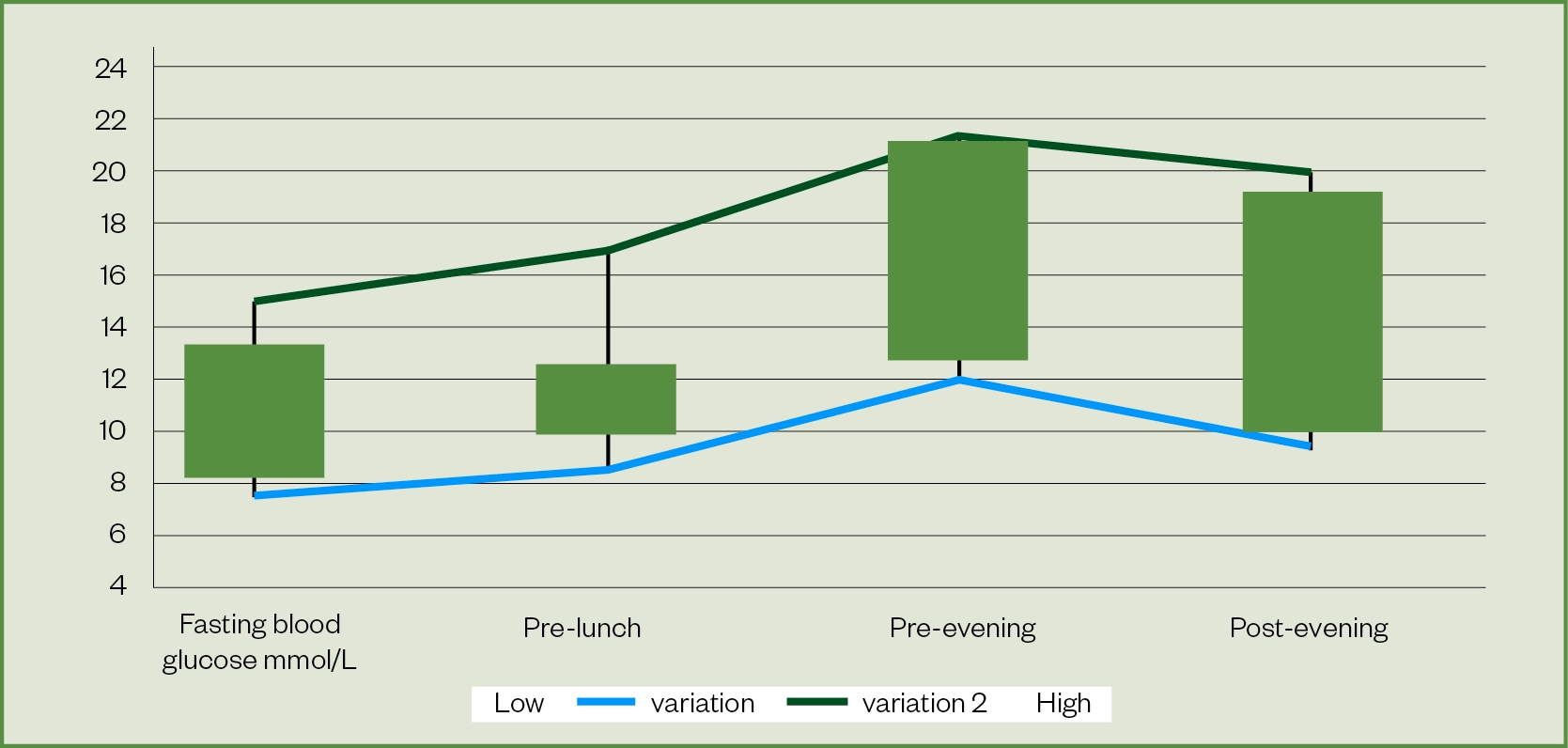

Ms S has poor glycaemic control and her HbA1c is outside the target range of 53–58mmol/mol, which increases the risk of complications[11]. She is struggling to achieve blood glucose targets across the whole day (see Figure 1).

Blood glucose is high on waking, rises from the morning and further significant rises occur in the afternoon. The night-time neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin dose tails off in the day. Postprandial blood glucose excursions after lunch and dinner require management.

Action is required to:

- Increase her current basal insulin to meet requirements for the whole day;

- Intensify her current insulin regimen to achieve glycaemic targets.

Management plan

Management should consider lifestyle interventions, optimisation of injection technique and intensification of the insulin regimen, while ensuring that cultural and other individual factors and patient preferences are incorporated.

1. A culturally adapted and individualised lifestyle education and support plan is required

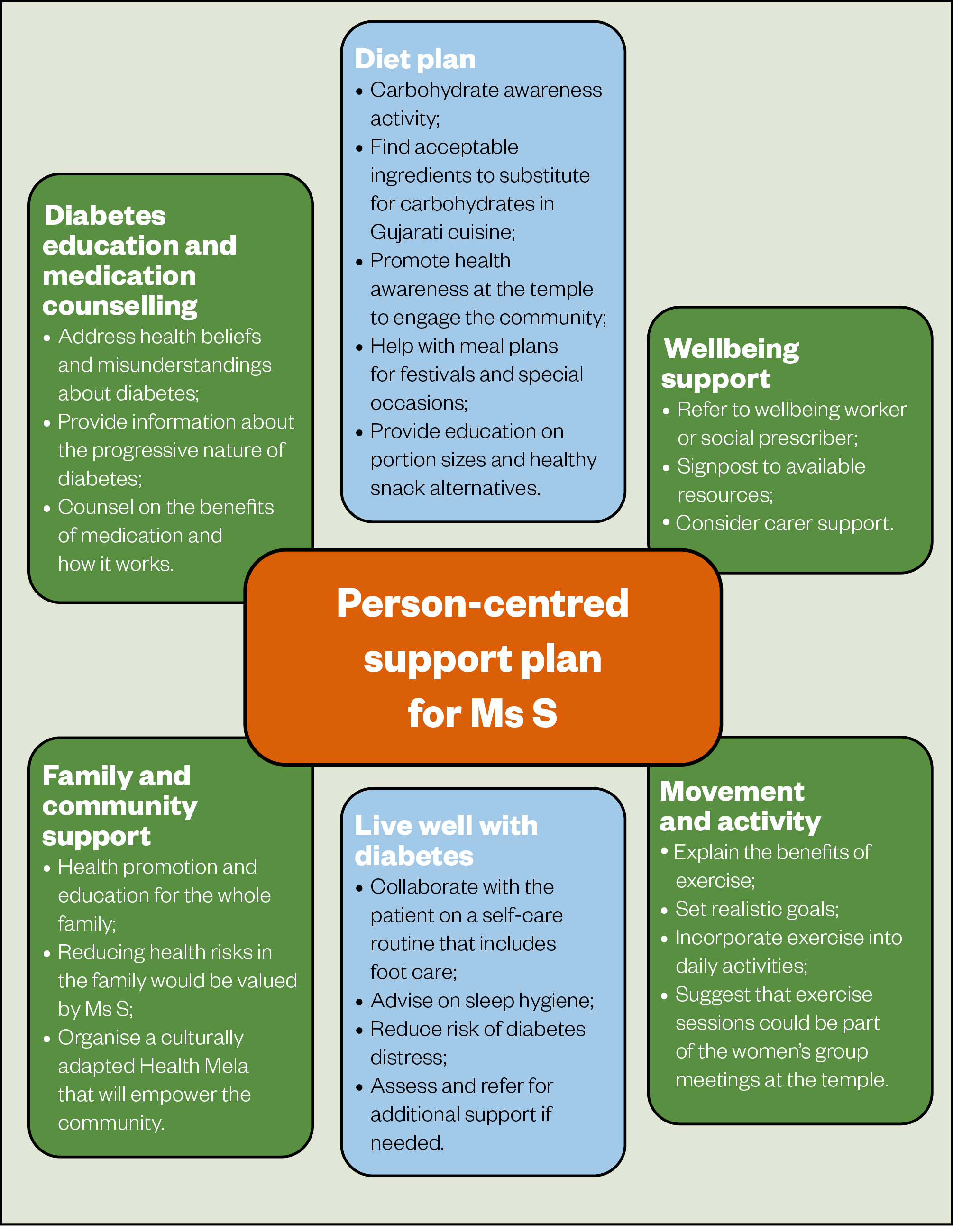

Culturally appropriate diabetes education has shown benefits over conventional care[12]. It is important to adapt the education to Ms S’s needs and create a person-centred individualised plan (see Figure 2).

2. Check and optimise injection technique

It is important to examine injection sites and check for signs of lipohypertrophy — when lumps of fat or scar tissue form under the skin caused by repeat injections or infusions in the same area of the body — for safe and effective insulin delivery. Lipohypertrophy has been associated with increased glycaemic variability[13].

To reduce the risk of lipohypertrophy, correct injection site rotation should be advised and needle length and usage should be checked; a 4mm pen needle injected at 90 degrees is safest[14–16]. Correct re-suspension of Humulin I insulin is important because if it is not done properly, glycaemic control can be erratic[17,18]. Figure 3 shows an example of lipohypertrophy[19].

3. Intensify the insulin regimen

Achieving blood glucose control will reduce symptomatic hyperglycaemia and reducing HbA1c will lower the risk of complications[11]. Evidence suggests good long-term glycaemic control, rather than over-tight control, is best, and that optimum blood glucose control is around 53 mmol/mol (7%)[20,21]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines emphasise individualised emphasise individualised targets and suggest stepping up treatment when HbA1c reaches 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) for those on medication, with the aim of reducing HbA1c to 53 mmol/mol[20]. Considering Ms S’s clinical picture, a suitable medium to long-term target is <58mmol/mol.

Ms S wants to feel less tired, which is linked to high glucose levels. She is keen to intensify her insulin to improve her glycaemic control but she worries about complications, having seen family members experience them. She wants to minimise any weight gain from insulin and have a flexible regimen that will fit in with her lifestyle.

Appraisal of insulin intensification options

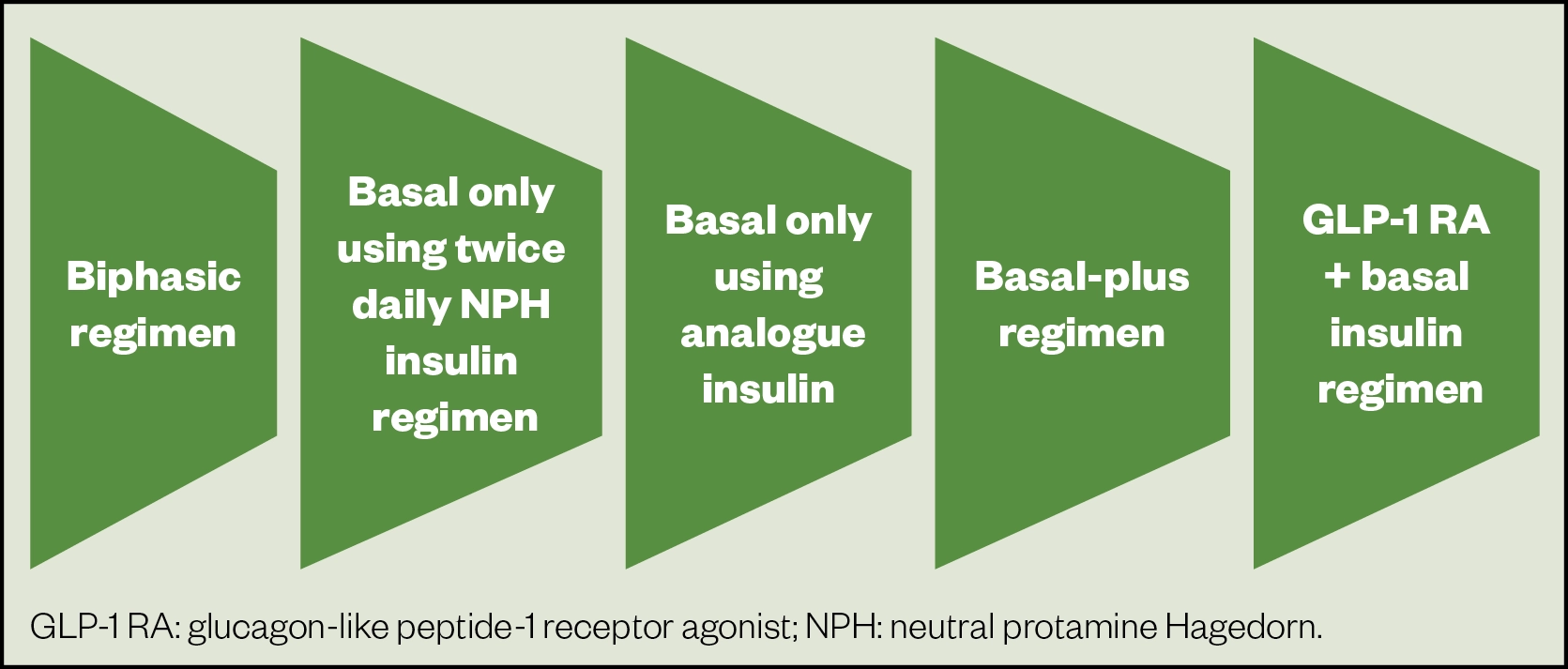

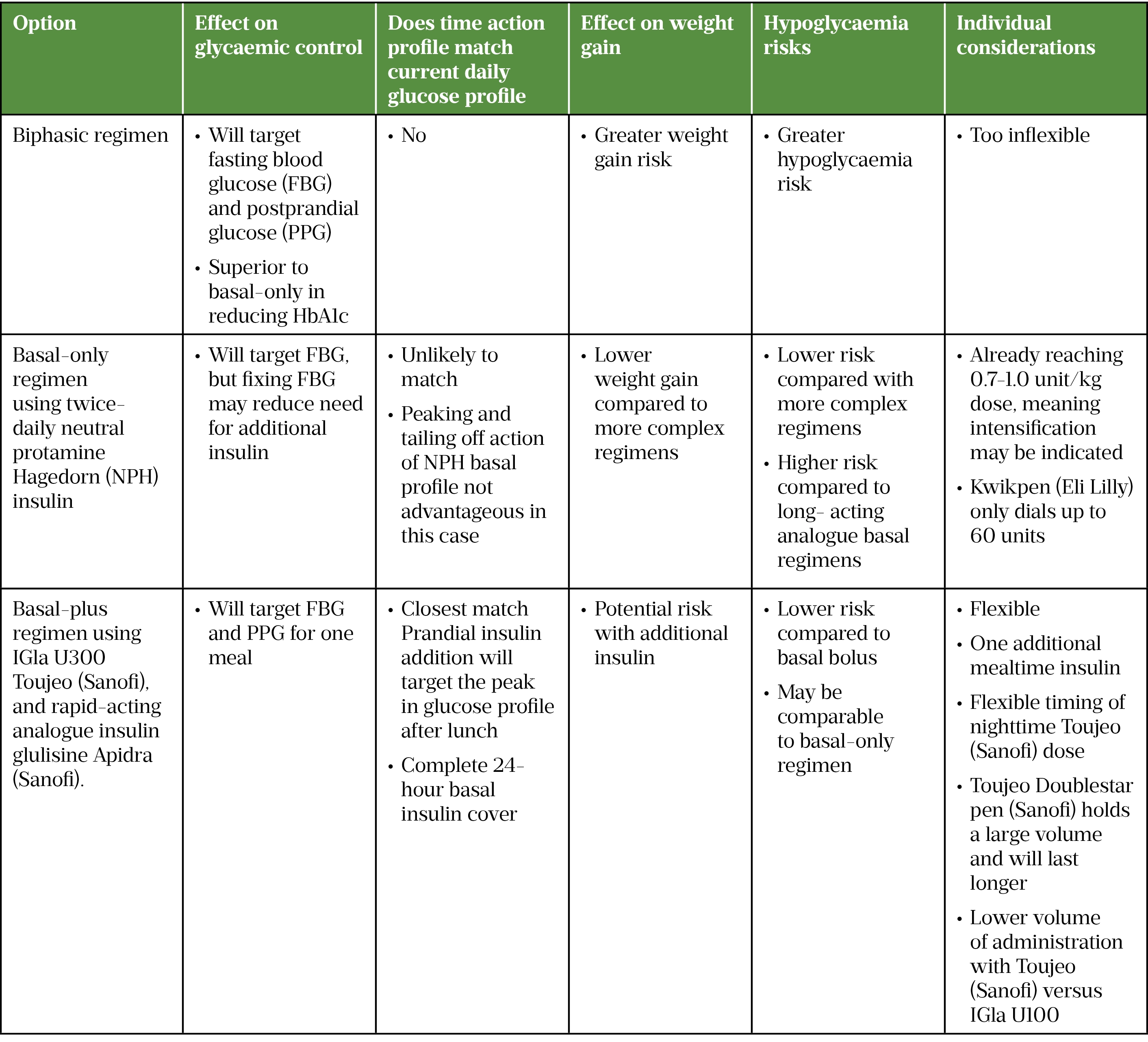

Potential options are shown in Figure 4.

Biphasic regimen

NICE recommends monitoring adults on a basal insulin regimen to assess the need for meal-time insulin or a premixed regimen, and suggests the latter if HbA1c is ≥75mmol/mol[22].

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidance lists premixed insulin as an option if HbA1c is ≥86mmol/mol[21].

Ms S’s weight is climbing and she has expressed concerns about additional weight gain. On reviewing Ms S’s lifestyle and dietary habits, a premixed regimen would be too inflexible for her changeable schedule and variable between-meals food intake.

Basal-only using twice-daily neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin or analogue insulin regimen

A basal-only regimen promotes the principle that fasting blood glucose (FBG) should be modified first. FBG has been shown to be the predominant problem when HbA1c is >58mmol/mol[23].

A single basal-only regimen has been show to be almost as effective as more complex regimens and result in fewer hypoglycaemic episodes and less weight gain[24]. When NPH insulin was compared with analogue insulin, a retrospective observational study published in 2018 found that those in NPH insulin had better glycaemic control than those on analogues[25]. There were also fewer hypoglycaemic events. As a result, the study authors suggested that NPH insulins should be used in preference to insulin analogues in type 2 diabetes unless there is a good reason not to do so.

NICE recommends NPH basal insulin as a first-line therapy alongside metformin in type 2 diabetes[20]. Ms S has the scope to allow further titration of the night-time basal insulin dose to reach an FBG target range of 5.5–6.5mmol/L.

Reviewing the current blood glucose trends and current dose per kg, further escalation beyond 1 unit/kg may be necessary; this may indicate insulin resistance and large insulin volumes may be required[26]. Using large volumes can slow absorption kinetics, reduce the effectiveness of insulin and can be more painful[27]. It may therefore be prudent to switch to an alternative regimen. On analysing the current insulin dose of 68 units, it should be noted that the Humalog Kwikpen device (Eli Lilly and Company) dials up to a maximum of 60 units, so a simpler delivery option may be beneficial.

If continuing with NPH insulin, splitting the dose to twice daily is a consideration, although the time action profile of this regimen is still unlikely to match Ms S’s requirements for flexibility. An extra injection will also be needed in the daytime. Also, Ms S may be planning to observe holy days, which would necessitate a reduced daytime insulin dose because lunch would be omitted[4].

As a result, matching a twice-daily NPH insulin regimen to meet Ms S’s needs would be challenging and other options should be explored.

NICE guidelines recommend the use of long-acting analogues in type 2 diabetes if the patient would otherwise require twice-daily NPH insulin and oral glucose-lowering medication[20].

The 2006 LANMET study compared therapy with metformin combined with insulin glargine (IGla) or NPH insulin[28]. Use of IGla was associated with fewer hypoglycaemic symptoms during the first 12 weeks of insulin therapy and with superior dinner-time glucose control throughout the study. Long-acting insulin analogues and NPH have similar glycaemic efficacy; however, overall symptoms and nocturnal hypoglycaemic events are lower in patients treated with the NPH[29].

Using a long-acting analogue, such as IGla U100 (100 units/mL) or U300 (300 units/mL), may help Ms S to improve her glucose readings throughout the whole day.

A patient-level meta-analysis of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies published in 2015 highlighted that IGIa U300 provides comparable glycaemic control to IGIa U100 with consistently less hypoglycaemia[30]. Using IGIa U300 for Ms S would mean that there is no basal insulin deficit during a 24-hour period owing to the prolonged pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles. Furthermore, the higher concentration in U300 means that the administration volume is smaller, making the injection more comfortable. Since the prolonged action extends beyond 24 hours, there is also more flexibility with dose timing, allowing up to three hours before or after the usual administration time[29].

In this case, it may also be appropriate to add a GLP-1-RA to Ms S’s basal insulin rather than increasing NPH or adding any further insulin to benefit her weight and to minimise her insulin dose. The cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1-RAs have been reported and the 2021 ABCD position statement supports their use in patients with cardiovascular disease risk if tolerated[31]. Being South Asian, Ms S could potentially be considered for GLP-1-RA therapy with a body mass index 35kg/m2.

In ABCD audits, exenatide and liraglutide with insulin demonstrated weight decreases HbA1c reductions[32,33]. Clinical evidence has supported the ABCD audits and has demonstrated that the drop in HbA1c from using a GLP-1-RA was similar to adding prandial insulin, with weight loss and reduced hypoglycaemia[34]. However, although more patients reported treatment satisfaction and a better quality of life with exenatide than insluin lispro, a larger proportion of patients with exenatide experienced treatment-emergent adverse events. Exenatide results in fewer nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes but more gastrointestinal side effects.

However, Ms S was adamant about not wanting to retrial this option. Promoting a therapy against the patient’s choice is likely to result in poor concordance and loss of patient–clinician trust in the management plan. Nevertheless, careful exploration of her concerns about this option could be something to discuss at a later date.

Basal-plus regimen

NICE guidelines suggest adding in prandial insulin if HbA1c is ≥75 mmol/mol[20]. Looking at Ms S’s readings and current insulin dose, the HbA1c target may not be achieved on a maximal dose of a long-acting analogue basal regimen alone. Excessive glycaemic excursions are occurring during the day and a prandial insulin injection before the meal most consistently contributing to the highest postprandial glycaemic peak is a logical step.

The 2018 ADA/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) consensus report proposed adding prandial insulin to the patient’s largest meal of the day if their HbA1c is above target despite adequately titrated basal insulin, or if the basal dose has reached 0.7–1.0 unit/kg[35]. Looking at the current basal dose and Ms S’s weight of 72kg, the basal dose is nearing 1 unit/kg and so the prandial addition is in keeping with guidance.

A proof-of-concept study published in 2011 investigating the effects of a single pre-prandial dose of insulin glulisine with titrated IGIa in type 2 diabetes reported that glulisine significantly improved glucose control without undesired effects[36]. Rates of hypoglycaemia and mean weight change were comparable between the basal-only and basal-plus groups.

A basal-plus regimen can provide glycaemic control equivalent to a full basal bolus regimen, with fewer injections of prandial insulin[24]. This regimen would be flexible enough for Ms S’s needs and could be adjusted according to changes to meals during special occasions and festivals.

Table 2 summarises the insulin regimen appraisal.

Preferred choice

The preferred option of insulin intensification for Ms S is the basal-plus regimen, using Toujeo U300 (active ingredient insulin glargine; Sanofi) + Novorapid (Novo Nordisk). It has the greatest chance of achieving glycaemic targets and meeting patient considerations. Prandial insulin dosing is flexible; if a meal is skipped or a larger meal is planned later, the timing of the dose can be adjusted according to need. One change should be made at a time, and basal insulin switched first. Then prandial insulin will be started using 4 units added to the meal with the highest postprandial excursion, as demonstrated by Owens et al[37]. This is in line with ADA/EASD guidance[35].

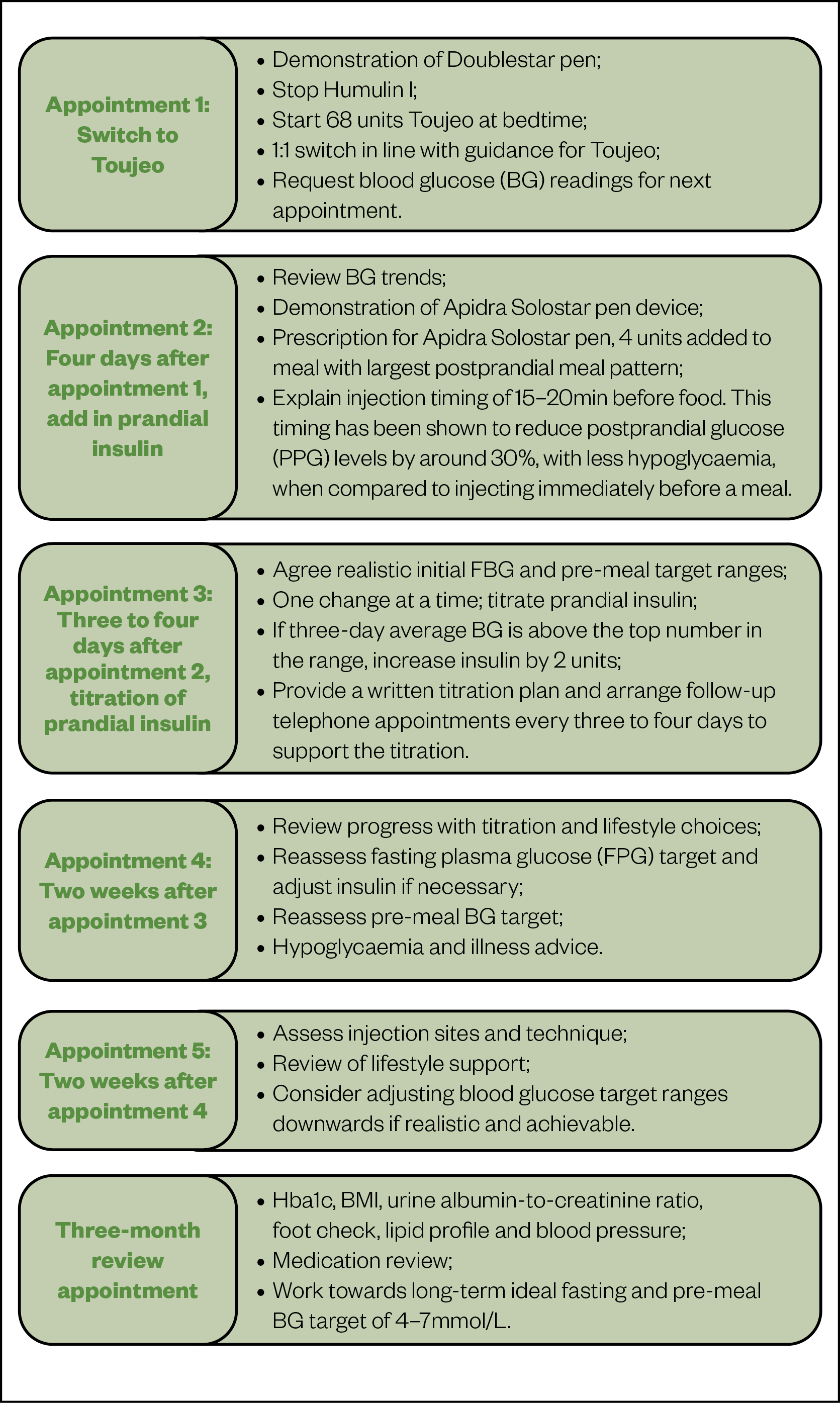

Figure 5 summarises the treatment plan and provides a structured pathway that details steps for switching, education, titration, follow up and review.

Outcomes

Ms S’s glycaemic control started improving over the first 3 months of the new regimen, reducing the risk of complications. Regular psychosocial support, medication counselling and diabetes education reduced the risk of diabetes burden and kept Ms S engaged.

In time, Ms S will be ready to self-manage titration of insulin. At an automatically scheduled blood test and medication review at three months, option of re-considering a GLP-1 RA was discussed.

Metformin was optimised by increasing the dose gradually up to 1g twice daily, and DPP4-I deprescribed. Over time, insulin requirements will further reduce and Ms S’s weight will remain under control.

Health inequalities

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s policy on health inequalities was drawn up in January 2023 following a presentation by Michael Marmot, director of the Institute for Health Equity, at the RPS annual conference in November 2022. The presentation highlighted the stark health inequalities across Britain.

While community pharmacies are most frequently located in areas of high deprivation, people living in these areas do not access the full range of services that are available. To mitigate this, the policy calls on pharmacies to not only think about the services it provides but also how it provides them by considering three actions:

- Deepening understanding of health inequalities

- This means developing an insight into the demographics of the population served by pharmacies using population health statistics and by engaging with patients directly through local community or faith groups.

- Understanding and improving pharmacy culture

- This calls on the whole pharmacy team to create a welcoming culture for all patients, empowering them to take an active role in their own care, and improving communication skills within the team and with patients.

- Improving structural barriers

- This calls for improving accessibility of patient information resources and incorporating health inequalities into pharmacy training and education to tackle wider barriers to care.

- 1Kumar S, Brodie J. Diabetes UK and South Asian Health Foundation recommendations on diabetes research priorities for British South Asians. Diabetes UK 2009. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2017-11/south_asian_report.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 2Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Bhopal R, et al. Diabetes Prevalence in Populations of South Asian Indian and African Origins. Epidemiology. 2011;22:563–7. doi:10.1097/ede.0b013e31821d1096

- 3Diabetes and CVD supplement: 2. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk in UK South Asians – an overview. Br J Cardiol. 2018. doi:10.5837/bjc.2018.s08

- 4Kalra S, Bajaj S, Gupta Y, et al. Fasts, feasts and festivals in diabetes-1: Glycemic management during Hindu fasts. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2015;19:198. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.149314

- 5Mahadevan M. Exploring Changes in Food Meanings and Food Choices Among Asian Indian Hindu Brahmins in State College, PA: A Grounded Theory Approach. Pennsylvania State University — Electronic Theses and Dissertations for Graduate School. 2003.https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/catalog/6196 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 6Talukdar J. Rituals and Embodiment: Class Differences in Religious Fasting Practices of Bengali Hindu Women. Sociological Focus. 2014;47:141–62. doi:10.1080/00380237.2014.916592

- 7Jayanti SV. Bhagavad Gita for Everyday Life. PURUSHARTHA: A Journal of Management, Ethics and Spirituality 2020;13.https://journals.smsvaranasi.com/index.php/purushartha/article/view/663

- 8Mahadevan S, Kannan S, Seshadri K, et al. Fasting practices in Tamil Nadu and their importance for patients with diabetes. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2016;20:858. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.192921

- 9Patel V, Morrissey J, Goenka N, et al. Diabetes care in the Hindu patient: cultural and clinical aspects. Diabetes & Vascular Disease. 2001;1:132–5. doi:10.1177/14746514010010021301

- 10Guess N. Lifestyle issues: Diet. In: Textbook of Diabetes. John Wiley & Sons 2017. 341–52.

- 11Stratton IM. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405–12. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405

- 12Creamer J, Attridge M, Ramsden M, et al. Culturally appropriate health education for Type 2 diabetes in ethnic minority groups: an updated Cochrane Review of randomized controlled trials. Diabet. Med. 2015;33:169–83. doi:10.1111/dme.12865

- 13Spollett G, Edelman SV, Mehner P, et al. Improvement of Insulin Injection Technique. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42:379–94. doi:10.1177/0145721716648017

- 14Blanco M, Hernández MT, Strauss KW, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of lipohypertrophy in insulin-injecting patients with diabetes. Diabetes & Metabolism. 2013;39:445–53. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2013.05.006

- 15Injection Technique Matters Best Practice in Diabetes Care. Trend UK. 2019.https://trenddiabetes.online/injection-technique-matters/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 16The UK Injection and Infusion Technique Recommendations 4th Edition. Fit 4 Diabetes. 2016.http://www.fit4diabetes.com/files/4514/7946/3482/FIT_UK_Recommendations_4th_Edition.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 17Eli Lilly. HUMULIN I KwikPen (Isophane) 100IU/ml suspension for injection SmPC. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8194/smpc (accessed Apr 2022).

- 18Jehle PM, Micheler C, Jehle DR, et al. Inadequate suspension of neutral protamine Hagendorn (NPH) insulin in pens. The Lancet. 1999;354:1604–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(98)12459-5

- 19Gentile S, Satta E, Strollo F, et al. Insulin-induced skin lipohypertrophies: A neglected cause of hypoglycemia in dialysed individuals with diabetes. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2021;15:102145. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.018

- 20Type 2 diabetes in adults: Management (NG28). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/NG28 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 21Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2015: A Patient-Centered Approach: Update to a Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;38:140–9. doi:10.2337/dc14-2441

- 22Wang C, Mamza J, Idris I. Biphasic vs basal bolus insulin regimen in Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabet. Med. 2015;32:585–94. doi:10.1111/dme.12694

- 23Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of Fasting and Postprandial Plasma Glucose Increments to the Overall Diurnal Hyperglycemia of Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881–5. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.3.881

- 24Raccah D, Huet D, Dib A, et al. Review of basal-plus insulin regimen options for simpler insulin intensification in people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2017;34:1193–204. doi:10.1111/dme.13390

- 25Lipska KJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, et al. Association of Initiation of Basal Insulin Analogs vs Neutral Protamine Hagedorn Insulin With Hypoglycemia-Related Emergency Department Visits or Hospital Admissions and With Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA. 2018;320:53. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7993

- 26Ovalle F. Clinical approach to the patient with diabetes mellitus and very high insulin requirements. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2010;90:231–42. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.06.025

- 27Cheung B, Ma R. Drug therapy: Special considerations in diabetes. In: Textbook of Diabetes. John Wiley & Sons 2016. 385–97.

- 28Yki-Järvinen H, Kauppinen-Mäkelin R, Tiikkainen M, et al. Insulin glargine or NPH combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes: the LANMET study. Diabetologia. 2006;49:442–51. doi:10.1007/s00125-005-0132-0

- 29Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, et al. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005613.pub3

- 30Ritzel R, Roussel R, Bolli GB, et al. Patient‐level meta‐analysis of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies: glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:859–67. doi:10.1111/dom.12485

- 31Basu A, Patel D, Winocour P, et al. Cardiovascular impact of new drugs (GLP-1 and gliflozins): the ABCD position statement. Br J Diabetes. 2021;21:132–48. doi:10.15277/bjd.2021.283

- 32Ryder B, Thong K. Findings from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) nationwide exenatide and liraglutide audits. Association of British Clinical Diabetologists Education. 2012.http://www.diabetologists-abcd.org.uk/GLP1_Audits/ABCD_Hot_Topics_2012.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 33Thong KY, Gupta PS, Cull ML, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes – NICE guidelines versus clinical practice. Br J Diabetes. 2014;14:52. doi:10.15277/bjdvd.2014.015

- 34Diamant M, Nauck MA, Shaginian R, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist or Bolus Insulin With Optimized Basal Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2763–73. doi:10.2337/dc14-0876

- 35Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2669–701. doi:10.2337/dci18-0033

- 36Sanofi. Toujeo 300 units/ml DoubleStar, solution for injection in a pre-filled SmPC . Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10277/smpc (accessed Apr 2022).

- 37Owens DR, Luzio SD, Sert-Langeron C, et al. Effects of initiation and titration of a single pre-prandial dose of insulin glulisine while continuing titrated insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes: a 6-month ‘proof-of-concept’’ study’. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2011;13:1020–7. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01459.x

2 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

really interesting article - very insightful and will support me in my clinical practice. I enjoyed learning about the holistic and individualised approach

very informative - will bear this in mind when reviewing patients. Thanks for a great article.