JOSE CALVO / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the different symptoms of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) caused by systemic dysfunction;

- Understand how immunophenotyping of CLL can help guide treatment;

- Know the available treatments for CLL and their indications.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is a form of blood cancer affecting the lymphocytes. The term ‘chronic’ derives from the fact that this type of leukaemia is slow growing, compared to acute leukaemia, which develops more rapidly1. In the UK, CLL is the most common leukaemia in adults, with an incidence of 3–4 per 100,000 per year. Median age at presentation is 72 years and it occurs twice as frequently in males as females2. CLL and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are the same disease, but CLL cancer cells are found mostly in the blood and bone marrow, while SLL cancer cells are found mostly in the lymph nodes3.

CLL commonly leads to immune dysfunction, especially hypogammaglobulinemia (i.e. decreased immunoglobulin levels), which increases the risk of infection. Infection remains a major cause of mortality and morbidity in CLL, with studies demonstrating that infection accounts for one-third to one-half of all deaths4.

The treatment for CLL has changed dramatically over the past two decades. First with the introduction of combination of chemo-immunotherapy agents (e.g. combinations with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab [an anti-CD20 antibody] and bendamustine, rituximab), and second with the discovery and availability of small molecule pathway inhibitors (e.g. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors [BTKis], phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors [PI3Kis] and B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors [BCL2is]). These advances in treatment have improved the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in people with CLL, as well as forcing clinicians to re-examine the relationship between immunoglobulin deficiencies in CLL, infection risk and survival4.

While changes in the treatment landscape have had a positive impact on patient mortality and morbidity, it poses new challenges for the medical team, including drug–drug interactions, adherence counselling and toxicity. Pharmacists are uniquely trained and equipped to help to manage the changing landscape of CLL care. Additional information can be found in The PJ Pod episode: ‘How can pharmacists best support patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia?’, published in September 2024.

Pharmacists can play an integral role in the comprehensive management of patients with CLL. With their unique perspective and medication-related expertise, pharmacists can add value and take the lead on many aspects of care for these patients. This includes providing chemotherapy education and comprehensive medication management to potentially conducting independent clinical follow-up visits5. Treatment with oral anticancer drugs is associated with a broad range of medication errors and side effects. Pharmacist involvement in the care of these patients can have a considerable positive impact on medication errors and patient satisfaction6.

Cancer learning ‘hub’

Pharmacists are playing an increasingly important role in supporting patients with cancer, working within multidisciplinary teams and improving outcomes.

However, in a rapidly evolving field with numbers of new cancer medicines is increasing and the potential for adverse effects, it is now more important than ever for pharmacists to have a solid understanding of the principles of cancer biology, its diagnosis and approaches to treatment and prevention.

This new collection of cancer content, brought to you in partnership with BeOne Medicines, provides access to educational resources that support professional development for improved patient

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of CLL is multifactorial and dependent on various factors, such as B-cell receptor pathway signalling, somatic mutations, genomic mutations and the CLL micro-environment7. Some patients with CLL have progressive disease and require therapy relatively soon after diagnosis, whereas others have highly indolent disease (one with little or no pain) that does not require treatment for many years; this variability reflects the intrinsic heterogeneity in the disease biology7.

B-cell receptor signalling plays an essential role in pathogenesis of CLL7. Two major molecular subgroups have been identified: those harbouring unmutated IG heavy-chain variable region (IGHV) genes (U-CLL, ≥98% identity with the germline); and those with mutated IGHV genes (MCLL). U-CLL originates from B cells that have not experienced the germinal centre, whereas M-CLL originates from post-germinal centre B cells8.

Several cellular components of the CLL micro-environment have been described, along with the signalling pathways involved in CLL homing, survival and proliferation, which now provides a rationale for targeting the CLL micro-environment9.

Understanding the pathogenesis of CLL has a direct correlation with treatment. For example, inhibitors of BCR signalling pathway are now standard of care for first-line and relapsed CLL. There is evidence that patients with 17p deletions do not respond to chemoimmunotherapy10.

Symptoms

Patients with early stage CLL may not be symptomatic. As the disease progresses, patients may develop recurrent infections, symptoms of anaemia (e.g. persistent tiredness, shortness of breath, easy bruising or bleeding), a high temperature, night sweats, enlarged lymph nodes in neck, axilla or groin, unintentional weight loss11. Other symptoms owing to specific systemic dysfunction are as below:

Symptoms owing to immune dysregulation

Quantitative and qualitative defects in immune response in almost all patients from the time of diagnosis. Immune suppression is manifested by predisposition to infection11.

Symptoms owing to autoimmune complications

Another complication of immune dysregulation is autoimmune cytopenias (e.g. autoimmune haemolytic anaemia and immune thrombocytopenia [ITP]), which affects 4–7% of patients. Autoimmune phenomena are frequently observed in patients with CLL and are mainly attributable to underlying dysfunctions of the immune system12.

Symptoms owing to bone marrow infiltration

Heavy infiltration of CLL in bone marrow can cause cytopenias that are not immune in nature. Depending on the nature of the infiltration, it can cause anaemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia. This can lead to complications of anaemia, infections and bleeding or bruising, respectively12.

Symptoms owing to Richter’s transformation

Richter syndrome (RS) describes the development of high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL/SLL). RS’s transformation to Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a very rare event, occurring in <1% of cases. The symptoms in patients with Richter’s transformation are related to high-grade lymphoma, such as loss of weight, loss of appetite and drenching night sweats. The prognosis for these patients is generally poor13.

Risk factors

The following have been shown to be risk factors for CLL:

- Family history: Research suggests that people with a first-degree relative with CLL have an 8.5 times higher risk of developing the disease than somebody without a family history14;

- Age: Globally, during the last 30 years, CLL-related incidence cases increased significantly with the age-standardised incidence rate rising from 0.76/100,000 persons in 1990 to 1.34/100,000 persons in 201915;

- Exposure to chemicals: Exposure to certain chemicals has been associated with increased risk of developing CLL. For example, exposure to Agent Orange, a herbicide used during the Vietnam War, led to increased incidence of CLL in war veterans16. Occupational exposure to certain pesticides (such as methomyl) led to increased incidence of CLL17;

- Sex and race: Men are twice as likely to get CLL compared to women14. DNA methylation differences between men and women have been shown to play a role in this18. CLL is more common in individuals of European decent compared to people of Asian or African descent19.

Diagnosis and assessment

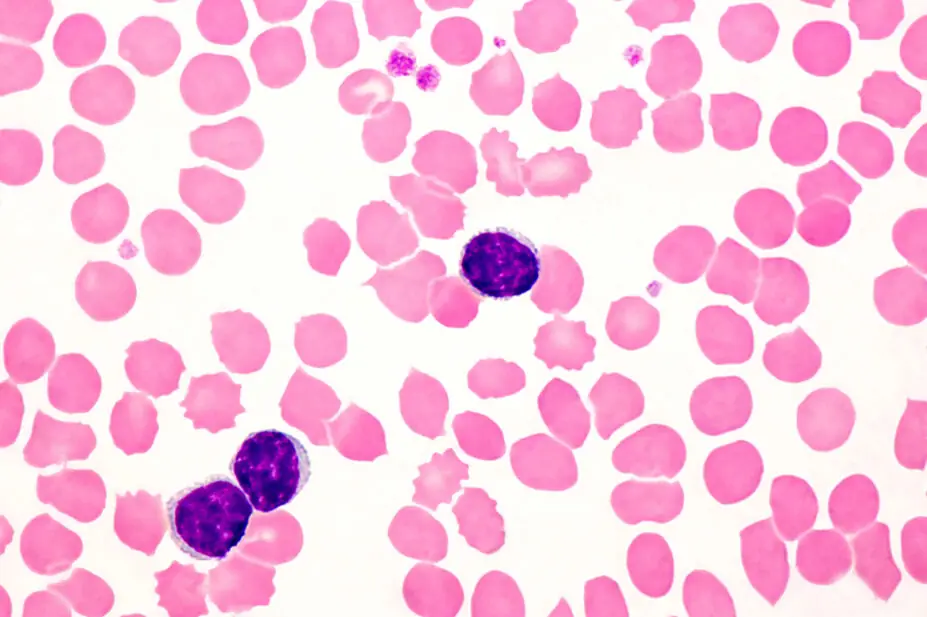

The diagnosis of CLL requires the presence of ≥5 × 109/L B lymphocytes (5000/μL) in the peripheral blood for the duration of at least three months20. The clonality of the circulating B lymphocytes needs to be confirmed by flow cytometry. The leukaemia cells found in the blood smear are characteristically small, mature lymphocytes with a narrow border of cytoplasm and a dense nucleus lacking discernible nucleoli and having partially aggregated chromatin20. The definition of SLL requires the presence of lymphadenopathy and the absence of cytopenia’s caused by a clonal marrow infiltrate, with diagnosis confirmed by histopathological evaluation of a lymph node biopsy20.

Staging

Consensus guidelines, published in 2008, detailed the assessments, diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with CLL20.

The immunophenotype of CLL is that the CLL lymphocytes exhibit a characteristic profile of CD19+, CD5+, CD23+, CD20+ low, CD200+, CD22+ low/negative, CD79b low/negative, CD43+ low, sIgκ+ or sIgλ+ low, sIgM+ low, CD11c+ low/negative, FMC7 negative, CD10 negative and CD103 negative21.

A scoring system allocates points to each of these factors which helps in diagnosis, based on the evaluation of five parameters: CD5+ (1 point), CD23+ (1 point), FMC7 negative (1 point), weak intensity of kappa/lambda chains (1 point), and weak or negative CD22/CD79b (1 point). The CLL score ranges between 5 (typical CLL cases) and 3 (less typical CLL cases). Scores of 0–2 exclude the diagnosis of CLL22. For patients with SLL, a tissue biopsy with presence of these markers would confirm the diagnosis of CLL22.

The above immunophenotype would help in ruling out other low-grade lymphomas, such as mantle cell lymphoma (CD5+, CD23-), hairy cell leukaemia (CD5-, CD23-, CD103 +) and marginal zone lymphoma (CD5-)23.

Two widely used staging systems are Rai and Binet, which were developed in the 1970s and give a good correlation about prognosis of CLL, these can be seen in Table 120,24.

Prognosis

Apart from staging, there are other factors that are used as prognostic markers, such as, pattern of bone marrow involvement, number of prolymphocytes in blood or bone marrow, age, gender, lymphocyte doubling time, absolute lymphocyte count and β2-microglobulin25.

Cytogenetic and molecular markers are important in confirming diagnosis and predicting prognosis of patients with CLL. Established prognostic markers and emerging ones can be seen in Table 226.

Genomic aberrations in CLL are important independent predictors of disease progression and survival. More than 80% of patients have some chromosomal alteration, the most frequent being a deletion in 13q (55%), a deletion in 11q (18%), trisomy of 12q (16%), a deletion in 17p (7%) and a deletion in 6q (7%)27.

The international working group for CLL-International Prognostic Index has a prognostic scoring system that combines genetic, biochemical and clinical parameters. A total of 3,472 treatment-naive patients were included in the full analysis dataset from 13 clinical trials. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed on various baseline factors and overall survival was the end-point. Using a weighted grading of the independent factors, a prognostic index was derived that identified four risk groups within the training dataset with significantly different overall survival at five years, the factors that make up these scores can be seen in Table 3 and Table 428.

Other investigations

Bone marrow biopsy is generally not needed for diagnosis of CLL, unless patient has cytopenias and the cause is unclear29.

A CT scan is not required for initial evaluation or for follow up30. As a baseline assessment, a staging CT scan of neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis would be useful before starting therapy30.

A lymph node biopsy is generally not required, unless there is diagnostic uncertainty. A lymph node or tissue biopsy is performed to establish the diagnosis of a transformation into an aggressive lymphoma (e.g. Richter transformation)30.

A PET scan can be useful to identify the best lymphoid area for establishing the diagnosis by biopsy30.

Management

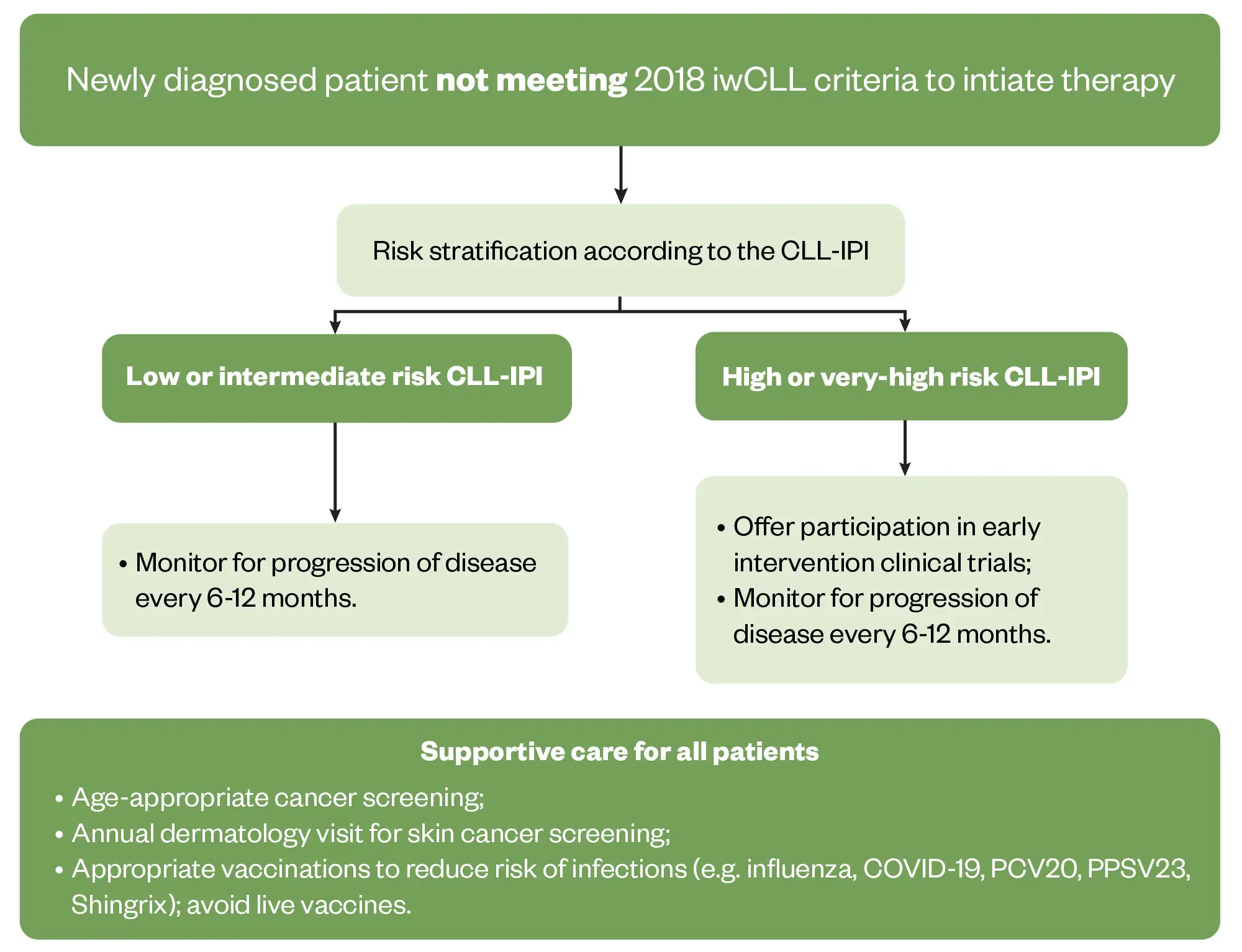

Most patients with CLL will not need treatment at diagnosis. Patients without symptoms and Rai stage 0-II or Binet A&B will undergo ‘active monitoring’, a term used when someone is not having treatment. During this period, patients are monitored and followed up regularly to look out for any signs of progression. In CLL, a patient could undergo active monitoring for several years.

Figure 1 outlines the monitoring approach suggested by the iwCLL for patients who do not fulfil the 2018 iwCLL criteria for treatment31.

Reproduced with permission from Hampel et al.

Front-line treatment

At the time of diagnosis, research has shown that 89% of patients had one or more comorbidities and 46% had at least one major comorbidity32; the most common being vascular, upper gastrointestinal, and endocrine33. As a result, fitness is an important factor when deciding type of treatment.

Chromosome 17p deletion and TP53 mutation status are also important considerations to guide treatment. Results from the German CLL 8 trial have shown that 17p deletion and TP53 mutations are associated with particularly poor outcomes with chemo-immunotherapy34.

For patients who have an intact TP53 status and are not fit for chemo-immunotherapy, treatment options are either combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab for a fixed duration; continuous treatment with a BTKi, such as acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib; or a combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax for a fixed duration35. All these treatments are permitted by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) via the cancer drug fund (CDF) in England35.

Four-year follow-up results of the CLL 14 trial (n=432) — which compared combination obinutuzumab and venetoclax with combination obinutuzumab and chlorambucil — showed significant improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with previously untreated CLL and co-existing conditions with venetoclax and obinutuzumab, compared with chlorambucil-obinutuzumab36. The ELEVATE TN study (n=535) showed that acalabrutinib — which is only approved for monotherapy by NICE, with or without obinutuzumab — significantly improved PFS over obinutuzumab-chlorambucil chemo-immunotherapy37. In the SEQUOIA trial (n=590), results showed that zanubrutinib significantly improved PFS versus bendamustine plus rituximab, with an acceptable safety profile38.

Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) has previously been the standard of care for patients who have an intact TP53 status and are fit for chemoimmunotherapy. The CLL 8 study (N=817) demonstrated that FCR is associated with significant toxicity in some patients and PFS for IgHV unmutated patients is not as good as IgHV mutated patients39. With the availability of other treatment options, many clinicians would prefer to use these over FCR.

However, the CLL 8 study has shown that among patients with mutated IGHV who receive front-line FCR and obtain an MRD-negative remission, extremely durable responses can be achieved in a large number of these patients39. Therefore, this may still be a viable option in patients who are fit and have IGHV mutated and TP53 unmutated status.

For patients with mutation or deletion of TP53, NICE-approved front-line treatment options are venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, or venetoclax monotherapy where a BTKi is contra-indicated.

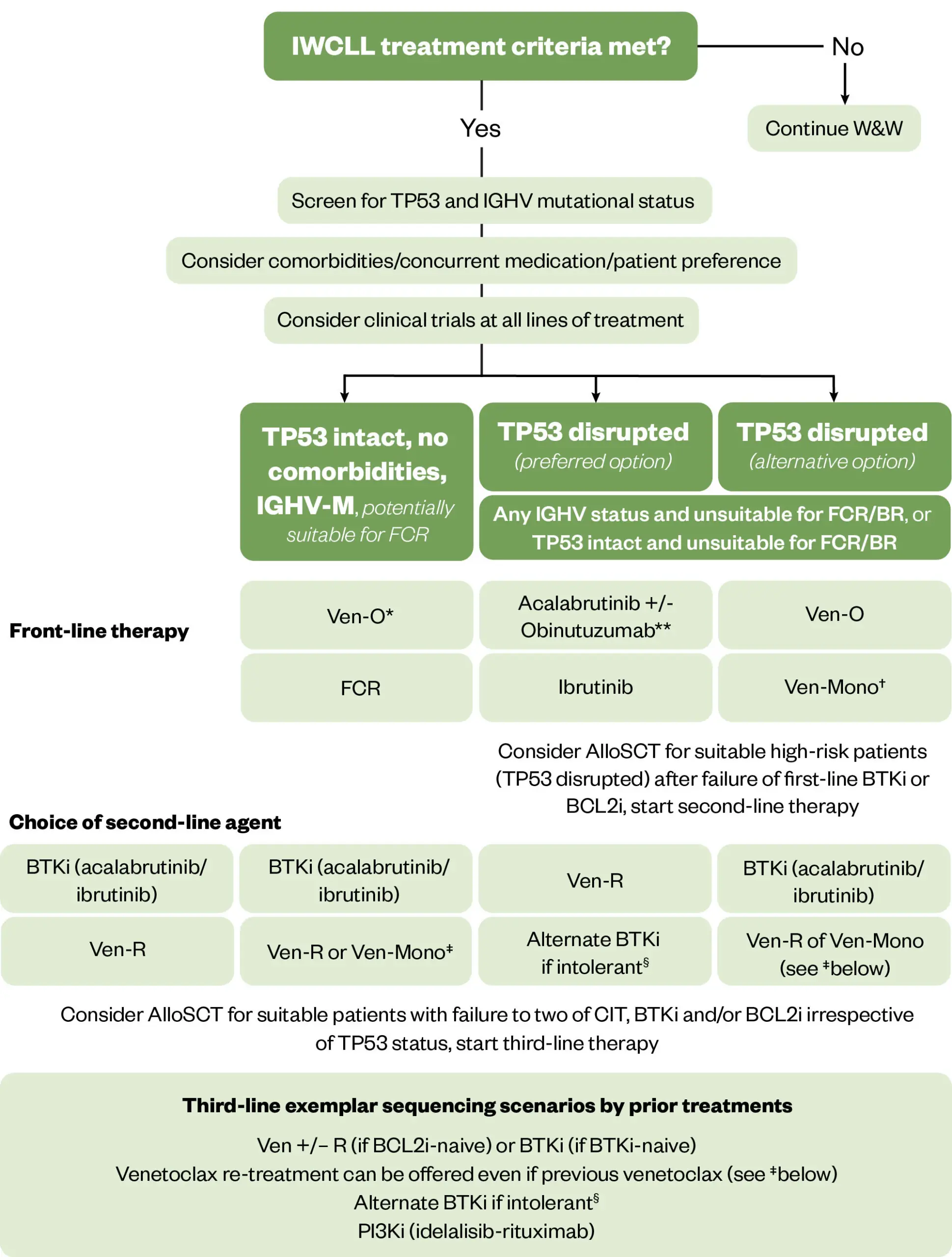

Figure 2 shows the treatment flow chart adapted from BCSH guidelines35.

R/R: Relapsed/refractory; CIT: Chemoimmunotherapy; BTKi: Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors; FCR: Fludarabine Cyclophosamide Rituximab; Ven-O: Venetoclax Obinutuzumab 12 months; Ven-R: Venetoclax-Rituximab 24 months; Veno-Mono: Single action continuous venetoclax; PI3Ki: Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase inhibitor; AlloSCT: allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

*Venetoclax-Obinutuzumab is available for NHSE patients for this patient population and is preferred; **Combination with Obinutuzumab is not licensed in the UK; †Alternate BTKi can be offered as an option if intolerant to initial BTKi choice and, when feasible, it is preferred over PI3Ki; ‡Only a first line option for TP53 disrupted patients who are ineligible for BTKi; §Venetoclax monotherapy can be offered to patients relapsing after fixed duration Venetoclax-based regimens.

Reproduced with permission from Walewska et al.; Wiley

Relapsed/refractory disease

Relapsed disease is when disease reappears after being in remission. The term ‘refractory’ is used to describe when the disease does not respond to treatment. The current licensed therapies for relapsed CLL are continuous BTKi (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib), BCL2i (venetoclax monotherapy or in combination with rituximab) and PI3Ki (idelalisib and rituximab)35. The ‘MURANO’ trial (n=389) showed that among patients with relapsed or refractory CLL, venetoclax plus rituximab resulted in significantly higher rates of progression-free survival than bendamustine plus rituximab — (the two-year rates of progression-free survival were 84.9% and 36.3%, respectively)40.

Continuous versus fixed-duration treatment

The RESONATE2 study demonstrated significant improvement in PFS and overall survival with continuous ibrutinib treatment in front line settings. However, high rates of treatment discontinuation were observed with long-term ibrutinib follow-up41. Real-world data also show significant discontinuation rates with long-term ibrutinib42; discontinuation is thought to be owing to adverse events.

Acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, which are second-generation covalent BTKis, have demonstrated superior PFS compared with chemo-immunotherapy in front-line settings in the ELEVATE TN and SEQUOIA trials37,38. In head-to-head trials with ibrutinib, the ELEVATE RR and ALPINE trials demonstrated comparatively lower rates of treatment discontinuation and lower frequencies of common adverse events and cardiac events overall compared with ibrutinib43,44.

Results from the CLL14 (n= 423) and CLL13 (n=926) trials showed that venetoclax plus obinutuzumab achieved superior PFS compared with chemoimmunotherapy for both subgroups45,46.

Fixed-duration treatment offers the advantage of stopping treatment once duration is complete, but requires frequent hospital visits while escalating with venetoclax and attendance to hospital for IV anti-CD 20 antibody infusion. For patients in whom attending hospital frequently can be challenging, continuous BTKi would be preferable.

Important considerations related to BTKi treatment

Toxicities are common and often associated with the off-target effects of BTKi treatment. The most common cardiovascular complications include atrial fibrillation, hypertension, heart failure, ventricular arrythmias and risk of bleeding35.

Pharmacists can help patients recognise and manage the side effects of BTKIs. Managing drug interactions in certain medication for atrial fibrillation, hypertension or heart failure can be crucial. Some patients may be taking anticoagulants, such as DOACs, which can increase the risk of bleeding when given alongside a BTKi. A review round that major bleeding was observed in 3.1% of 2,838 patients on ibrutinib (without antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants), this was increased by the addition of antiplatelet therapy with or without anticoagulant therapy to 4.4%, and by the addition of anticoagulant therapy with or without antiplatelet therapy to 6.1%47. Appropriate dose reductions may be advisable, which could be managed by a pharmacist in the clinic.

Additional information on the adverse effects of BTKis and the role of pharmacists in their management can be found in ‘BTK inhibitors: what pharmacists need to know’.

Tumour lysis syndrome

As the most common disease-related emergency encountered by physicians caring for patients with haematologic cancers, tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) develops most often in patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or acute leukaemia, and in patients with CLL who start treatment with Venetoclax. TLS occurs when tumour cells release their contents into the bloodstream, either spontaneously or in response to therapy, leading to the characteristic findings of hyperuricemia, hyperkalaemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcaemia48,49. These electrolyte and metabolic disturbances can progress to clinical toxic effects, including renal insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmias, seizures and death owing to multiorgan failure48,49.

A recognised complication of venetoclax, both biochemical and clinical TLS have been reported in clinical trials. Most hospitals now have established protocols for escalating the venetoclax dose to prevent TLS as per the drug prescribing information provided by the manufacturer50.

Pharmacists in clinics can assist in this management by advising on appropriate dosing and fluid intake, supportive drug management, helping with patient education and the promotion of adherence, ensuring the appropriate timing of blood testing during dose escalation, and collaboration with doctors and nurses for actions to be taken if TLS monitoring results are abnormal (e.g. findings of hyperuricemia, hyperkalaemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcaemia) .

Infusion reactions

The occurrence of infusion-related reactions (IRR), especially during the first infusion, is one of the main concerns of rituximab51.

Infusion reactions can be reduced or prevented by taking the following precautions beforehand:

- Patient should be asked about medical history, previous allergic disorders, atopic status and concomitant treatments;

- Appropriate pre-medications should be given (e.g. antihistamines and paracetamol)

- An updated protocol for the management of IRs should be at hand, as well as the medical equipment needed for resuscitation52.

Infusion reactions can occur with obinituzumab, similar to rituximab. In one study, it was noted that grade III or IV infusion-related reactions occurred in 20% of patients during the first infusion of obinutuzumab, but there were no grade 3 or 4 reactions during subsequent obinutuzumab infusions. No deaths were associated with infusion-related reactions53.

Pathophysiology of obinutuzumab IRRs is poorly understood and IRRs are considered to be multifactorial events with some of identified risk factors being drug dose and speed of infusion, premedication, concomitant medications, comorbidities, genetic predisposition and tumour burden54.

Supportive care

CLL associated auto-immune cytopenias are initially managed with steroids, either alone or in association with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, such as rituximab. When these directed therapies are not sufficient to control auto-immune manifestations, a CLL directed treatment is recommended12.

Hypogammaglobulinemia (low serum levels of IgG and IgA with variable IgM) is a frequent complication associated with CLL55. The use of IV immunoglobulin replacement is recommended for individual situations of hypogammaglobulinemia and repeated infections.

NHS England guidelines recommend replacement therapy for patients who:

- Suffer recurrent or severe bacterial infections despite six months of continuous oral antibiotic therapy;

- Have a total IgG <4 g/L; and

- Have documented failure to respond to polysaccharide vaccine challenge56.

People with CLL should receive the seasonal flu vaccine annually owing to their increased risk of mortality from invasive pneumococcal infection. In line with the updated Department of Health recommendations, they should also receive, the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PPV13) followed by the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) at least two months later57.

Live vaccines should not be given and it is recommended that patients with CLL should avoid contact with children who have received the live nasal influenza vaccine for seven days58. The recombinant varicella (shingles) vaccine is safe and is available for people in the UK with CLL aged 70–79 years59. COVID-19 vaccination is recommended in line with the government guidelines as in the Green Book, which provides the latest information on UK vaccines and vaccination procedures60.

Information on additional support considerations and how pharmacists can help best support patients undergoing CLL treatment can be found in ‘How can pharmacists best support patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia?’

Conclusion

Incorporating pharmacists into CLL clinics alongside doctors and nurses can improve patient care because pharmacists can provide education to patient and care givers, while helping with prescribing, dispensing and distributing of any medication. Pharmacists can also offer help with monitoring and check on compliance.

Best practice

- Most patients do not need treatment straight away — a watch and wait strategy is employed.

- It is important to check cytogenetics and molecular markers prior to starting treatment;

- Fixed duration and continues treatment options are available; depending upon individual characteristics, one type of treatment may be preferred over other;

- Careful attention needs to be given to the potential toxicity of each treatment; in particular, risk of TLS, risk of infusion reaction, risk of bleeding and cardiovascular risks;

- Clinical trials help in fine tuning treatment and also help is developing new standard of care, therefore patients should be encouraged to enter clinical trials, where available; however, it should be noted that not all centres will have access to clinical trials for CLL.

Patient counselling and support

Various charities and support organisations provide valuable support to information to patients with CLL, some of which are listed here:

- 1.Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Mayo Clinic. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20352428

- 2.Lymphoid Malignancies Part 4: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) and B-prolymphocytic Leukaemia (B-PLL). Pan-London Haemato-Oncology Clinical Guidelines. 2020. Accessed November 2024. https://rmpartners.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Pan-London-CLL-Guidelines-Jan-2020.pdf

- 3.CLL/SLL. National Cancer Institute. Accessed November 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cll-sll

- 4.Crassini KR, Best OG, Mulligan SP. Immune failure, infection and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2018;103(7):e329-e329. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.196543

- 5.Chen KY, Brunk KM, Patel BA, et al. Pharmacists’ Role in Managing Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Pharmacy. 2020;8(2):52. doi:10.3390/pharmacy8020052

- 6.Dürr P, Schlichtig K, Kelz C, et al. The Randomized AMBORA Trial: Impact of Pharmacological/Pharmaceutical Care on Medication Safety and Patient-Reported Outcomes During Treatment With New Oral Anticancer Agents. JCO. 2021;39(18):1983-1994. doi:10.1200/jco.20.03088

- 7.Zhang S, Kipps TJ. The Pathogenesis of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2014;9(1):103-118. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-163955

- 8.Julio Delgado, Ferran Nadeu, Dolors Colomer, Elias Campo. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: from molecular pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. haematol. 2020;105(9):2205-2217. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.236000

- 9.ten Hacken E, Burger JA. Microenvironment interactions and B-cell receptor signaling in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Implications for disease pathogenesis and treatment. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Cell Research. 2016;1863(3):401-413. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.07.009

- 10.Jones J, Mato A, Coutre S, et al. Evaluation of 230 patients with relapsed/refractory deletion 17p chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with ibrutinib from 3 clinical trials. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(4):504-512. doi:10.1111/bjh.15421

- 11.Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126(5):573-581. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-03-567388

- 12.Vitale C, Montalbano MC, Salvetti C, et al. Autoimmune Complications in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in the Era of Targeted Drugs. Cancers. 2020;12(2):282. doi:10.3390/cancers12020282

- 13.Tsimberidou A, Keating MJ. Richter syndrome. Cancer. 2005;103(2):216-228. doi:10.1002/cncr.20773

- 14.Slager SL, Lanasa MC, Marti GE, et al. Natural history of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis among relatives in CLL families. Blood. 2021;137(15):2046-2056. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006322

- 15.Yao Y, Lin X, Li F, Jin J, Wang H. The global burden and attributable risk factors of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. BioMed Eng OnLine. 2022;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12938-021-00973-6

- 16.Mescher C, Gilbertson D, Randall NM, et al. The impact of Agent Orange exposure on prognosis and management in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a National Veteran Affairs Tumor Registry Study. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2017;59(6):1348-1355. doi:10.1080/10428194.2017.1375109

- 17.Benavente Y, Costas L, Rodríguez-Suarez MM, et al. Occupational Exposure to Pesticides and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia in the MCC-Spain Study. IJERPH. 2020;17(14):5174. doi:10.3390/ijerph17145174

- 18.Lin S, Liu Y, Goldin LR, et al. Sex-related DNA methylation differences in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Biol Sex Differ. 2019;10(1). doi:10.1186/s13293-018-0213-7

- 19.Yang S, Varghese AM, Sood N, et al. Ethnic and geographic diversity of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2020;35(2):433-439. doi:10.1038/s41375-020-01057-5

- 20.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute–Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446-5456. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906

- 21.Oscier D, Fegan C, Hillmen P, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2004;125(3):294-317. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04898.x

- 22.Matutes E, Owusu-Ankomah K, Morilla R, et al. The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia. 1994;8(10):1640-1645. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7523797

- 23.Cabeçadas J, Nava VE, Ascensao JL, Gomes da Silva M. How to Diagnose and Treat CD5-Positive Lymphomas Involving the Spleen. Current Oncology. 2021;28(6):4611-4633. doi:10.3390/curroncol28060390

- 24.Gribben JG. How I treat CLL up front. Blood. 2010;115(2):187-197. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-08-207126

- 25.Furman RR. Prognostic Markers and Stratification of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Hematology. 2010;2010(1):77-81. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.77

- 26.Lee J, Wang YL. Prognostic and Predictive Molecular Biomarkers in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2020;22(9):1114-1125. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2020.06.004

- 27.Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. Genomic Aberrations and Survival in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(26):1910-1916. doi:10.1056/nejm200012283432602

- 28.An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL-IPI): a meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(6):779-790. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30029-8

- 29.Baliakas P, Kanellis G, Stavroyianni N, et al. The role of bone marrow biopsy examination at diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a reappraisal. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2013;54(11):2377-2384. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.780653

- 30.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018;131(25):2745-2760. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-09-806398

- 31.Hampel PJ, Parikh SA. Correction: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment algorithm 2022. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12(12). doi:10.1038/s41408-022-00775-6

- 32.Thurmes P, Call T, Slager S, et al. Comorbid conditions and survival in unselected, newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2008;49(1):49-56. doi:10.1080/10428190701724785

- 33.Villavicencio A, Solans M, Zacarías-Pons L, et al. Comorbidities at Diagnosis, Survival, and Cause of Death in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Population-Based Study. IJERPH. 2021;18(2):701. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020701

- 34.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164-1174. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61381-5

- 35.Walewska R, Parry‐Jones N, Eyre TA, et al. Guideline for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2022;197(5):544-557. doi:10.1111/bjh.18075

- 36.Al‐Sawaf O, Zhang C, Robrecht S, et al. VENETOCLAX‐OBINUTUZUMAB FOR PREVIOUSLY UNTREATED CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA: 4‐YEAR FOLLOW‐UP ANALYSIS OF THE RANDOMIZED CLL14 STUDY. Hematological Oncology. 2021;39(S2). doi:10.1002/hon.49_2880

- 37.Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzumab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE-TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1278-1291. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30262-2

- 38.Correction to Lancet Oncol 2022; 23: 1031–43. The Lancet Oncology. 2023;24(3):e106. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(23)00073-6

- 39.Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood. 2016;127(2):208-215. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-06-651125

- 40.Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. Venetoclax–Rituximab in Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1107-1120. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1713976

- 41.Barr PM, Owen C, Robak T, et al. Up to 8-year follow-up from RESONATE-2: first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia . Blood Advances. 2022;6(11):3440-3450. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006434

- 42.Huntington SF, De Nigris E, Puckett J, et al. Real-World Treatment Patterns and Outcomes after Ibrutinib Discontinuation Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: An Observational Study. Blood. 2022;140(Supplement 1):7939-7940. doi:10.1182/blood-2022-155903

- 43.Byrd JC, Hillmen P, Ghia P, et al. Acalabrutinib Versus Ibrutinib in Previously Treated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Results of the First Randomized Phase III Trial. JCO. 2021;39(31):3441-3452. doi:10.1200/jco.21.01210

- 44.Hillmen P, Brown JR, Eichhorst BF, et al. ALPINE: zanubrutinib versus ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2020;16(10):517-523. doi:10.2217/fon-2019-0844

- 45.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and Obinutuzumab in Patients with CLL and Coexisting Conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(23):2225-2236. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1815281

- 46.Eichhorst B, Niemann C, Kater AP, et al. A Randomized Phase III Study of Venetoclax-Based Time-Limited Combination Treatments (RVe, GVe, GIVe) Vs Standard Chemoimmunotherapy (CIT: FCR/BR) in Frontline Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) of Fit Patients: First Co-Primary Endpoint Analysis of the International Intergroup GAIA (CLL13) Trial. Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):71-71. doi:10.1182/blood-2021-146161

- 47.von Hundelshausen P, Siess W. Bleeding by Bruton Tyrosine Kinase-Inhibitors: Dependency on Drug Type and Disease. Cancers. 2021;13(5):1103. doi:10.3390/cancers13051103

- 48.Howard S, Jones D, Pui C. The tumor lysis syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1844-1854. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0904569

- 49.Gribben JG. Practical management of tumour lysis syndrome in venetoclax‐treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2019;188(6):844-851. doi:10.1111/bjh.16345

- 50.Venclyxto 10 mg film-coated tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2267/smpc#gref

- 51.Paul F, Cartron G. Infusion-related reactions to rituximab: frequency, mechanisms and predictors. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2019;15(4):383-389. doi:10.1080/1744666x.2019.1562905

- 52.Roselló S, Blasco I, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, Jordan K. Management of infusion reactions to systemic anticancer therapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Annals of Oncology. 2017;28:iv100-iv118. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx216

- 53.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus Chlorambucil in Patients with CLL and Coexisting Conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101-1110. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1313984

- 54.Dawson K, Moran M, Guindon K, Wan H. Managing Infusion-Related Reactions for Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Receiving Obinutuzumab. CJON. 2016;20(2):E41-E48. doi:10.1188/16.cjon.e41-e48

- 55.Noto A, Cassin R, Mattiello V, Bortolotti M, Reda G, Barcellini W. Should treatment of hypogammaglobulinemia with immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IgRT) become standard of care in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia? Front Immunol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1062376

- 56.Clinical Commissioning Policy for the use of therapeutic immunoglobulin (Ig) England . NHS England. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://igd.mdsas.com/wp-content/uploads/ccp-for-the-use-of-therapeutic-immunoglobulin-england-2024-v4.pdf

- 57.Pneumococcal: the green book, chapter 25. UK Health Security Agency. 2023. Accessed November 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pneumococcal-the-green-book-chapter-25

- 58.Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine [LAIV] (The Nasal Spray Flu Vaccine). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Accessed November 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccine-types/nasalspray.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/nasalspray.htm

- 59.Shingles immunisation programme: introduction of Shingrix® letter. Public Health England. 2021. Accessed November 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/shingles-immunisation-programme-introduction-of-shingrix-letter

- 60.COVID-19: the green book, chapter 14a. UK Health Security Agency. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-the-green-book-chapter-14a